Feral Historian

Published 24 Oct 2025Niven and Pournelle’s tale is one of the classics of the alien invasion genre and is deserving of more attention these days than it gets. Space elephants, asteroid strikes, and Orion battleships. Let’s get to it.

This one has been sitting in the WiP folder since early spring. There’s not much Footfall art out there and for whatever reason … I can’t seem to draw elephants.

00:00 Intro

03:25 The Herd(s)

07:13 The Foot and Michael

10:13 Flushing the Story

12:33 Launch and Negotiations

15:50 Takeaways

18:06 Rounding Corners

(more…)

February 27, 2026

Footfall and Cultural Blindspots

June 6, 2025

Marc Garneau, the first Canadian in space, RIP

The career of Marc Garneau is summarized by Tom Spears for The Line:

Astronaut Marc Garneau, with a camera in hand, floats in the hatchway that leads from Unity to Pressurized Mating Adapter-3 (PMA-3), which leads to Endeavour. Garneau, STS-97 mission specialist representing the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), and his four crew mates went into the International Space Station (ISS) following hatch opening. The photograph was taken with a digital still camera, 8 December 2000.

NASA photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Marc Garneau died Wednesday, at the age of 76. His passing was announced by his wife, Pam, who said that he’d been surrounded by family at the end, and had received excellent care during an unspecified short illness. (Other reports have cited cancer as the ailment.) The news was met with an immediate outpouring of grief from Canadians from across the political spectrum, as befitted a man of his profile and stature.

He had earned that profile gradually over the decades. Back in 1983 Garneau was a young naval officer with a fine pedigree — graduate of Royal Military College, PhD in electrical engineering from Imperial College London — but unknown to most Canadians. Then he joined our country’s first group of astronauts, becoming an instant celebrity.

Even more sudden was his first assignment. He was named to a space shuttle crew that would fly the following year — lightning-fast career advancement, considering he had not yet undergone the usual training as a mission specialist in NASA’s astronaut school.

That vaulted him ahead of many more senior astronauts, and he felt it keenly. He told the Ottawa Citizen years later that he felt his colleagues’ eyes “boring holes in my back” as he walked by them. Crewmate Dave Leestma later recalled how the rookie gained the respect of those around him through quiet competence.

Indeed, Garneau always looked calm, but his mother, Jean, said as he prepared for a second flight in 1996: “There’s a lot of controlled excitement there, and happiness … He figures he’s very, very lucky.”

[…]

“Everybody was always brutally honest about how they screwed up … about how we let the team down,” Garneau says. “If we’re not going to be very honest with each other, if we’re going to find excuses … Nobody tries to evade responsibility.”

Given his background and experience, I wonder how he was able to handle being a member of the Liberal government of the day, where evading responsibility was perhaps their top competency.

October 15, 2024

QotD: The Mandela Effect

Do you remember where you were when you heard that planes had struck the World Trade Center? That the Challenger shuttle had exploded? Or that Nelson Mandela had been released?

Your memories may be different from mine, but not as different as Fiona Broome’s. I remember watching the live TV footage of Nelson Mandela walking to freedom after 27 years in captivity, while Broome, an author and paranormal researcher, remembers Nelson Mandela dying in prison in the 1980s.

When Broome discovered that she was not the only person to remember an alternative version of events, she started a website about what she dubbed “the Mandela Effect”. On it, she collected shared memories that seemed to contradict the historical record. (The site is no longer online but, never fear, Broome has published a 15-volume anthology of these curious recollections.)

Mandela, of course, did not die in prison. On a recent trip to South Africa, I visited Robben Island, where he and many others were incarcerated in harsh conditions, to speak to former prisoners and former prison guards, and to wander around a city emblazoned with images of the smiling, genial, elderly statesman. How could it be that anyone remembers differently?

The truth is that our memories are less reliable than we tend to think. The cognitive psychologist Ulric Neisser vividly remembered where he was when he heard that the Japanese had launched a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7 1941. He was listening to a baseball game on the radio when the broadcast was interrupted by the breaking news, and he rushed upstairs to tell his mother. Only later did Neisser realise that his memory, no matter how vivid, must be wrong. There are no radio broadcasts of baseball in December.

On January 28 1986, the Challenger space shuttle exploded shortly after launch; a spectacular and highly memorable tragedy. The morning after, Neisser and his colleague Nicole Harsch asked a group of students to write down an account of how they learnt the news. A few years later, Neisser and Harsch went back to the same people and made the same requests. The memories were complete, vivid and, for a substantial minority of people, completely different from what they had written down a few hours after the event.

What’s stunning about these results is not that we forget. It’s that we remember, clearly, in detail and with great confidence, things that simply did not happen.

Tim Harford, “The detours on memory lane”, Tim Harford, 2024-06-20.

August 9, 2024

A crisis of competence

Glenn “Instapundit” Reynolds on one of the biggest yet least recognized issues of most modern nations — our overall declining institutional competence:

Almost everywhere you look, we are in a crisis of institutional competence.

The Secret Service, whose failures in securing Trump’s Butler, PA speech are legendary and frankly hard to believe at this point, is one example. (Nor is the Butler event the Secret Service’s first embarrassment.)

The Navy, whose ships keep colliding and catching fire.

Major software vendor Crowdstrike, whose botched update shut down major computer systems around the world.

The United States government, which built entire floating harbors to support the D-Day invasion in Europe, but couldn’t build a workable floating pier in Gaza.

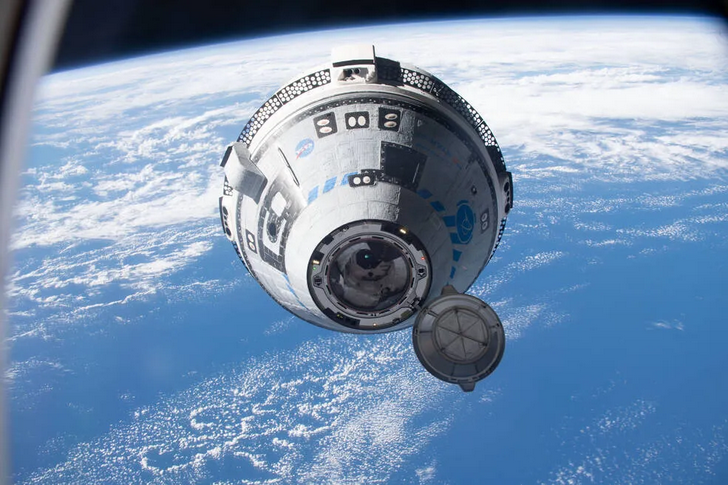

And of course, Boeing, whose Starliner spacecraft is stuck, apparently indefinitely, at the International Space Station. (Its crew’s six-day mission, now extended perhaps into 2025, is giving off real Gilligan’s Island energy.) At present, Starliner is clogging up a necessary docking point at the ISS, and they can’t even send Starliner back to Earth on its own because it lacks the necessary software to operate unmanned – even though an earlier build of Starliner did just that.

Then there are all the problems with Boeing’s airliners, literally too numerous to list here.

Roads and bridges take forever to be built or repaired, new airports are nearly unknown, and the Covid response was extraordinary for its combination of arrogant self-assurance and evident ineptitude.

These are not the only examples, of course, and readers can no doubt provide more (feel free to do so in the comments) but the question is, Why? Why are our institutions suffering from such widespread incompetence? Americans used to be known for “know how,” for a “can-do spirit”, for “Yankee ingenuity” and the like. Now? Not so much.

Americans in the old days were hardly perfect, of course. Once the Transcontinental Railroad was finished and the golden spike driven in Promontory, Utah, large parts of it had to be reconstructed for poor grading, defective track, etc. Transport planes full of American paratroopers were shot down during the invasion of Sicily by American ships, whose gunners somehow confused them for German bombers. But those were failures along the way to big successes, which is not so much the case today.

But if our ancestors mostly did better, it’s probably because they operated closer to the bone. One characteristic of most of our recent failures is that nobody gets fired. (Secret Service Director Kim Cheatle did resign, eventually, but nobody fired her, and I think heads should have rolled on down the line).

January 15, 2023

QotD: The uncertain “certainties” of war in space

The comments for that post were very active with suggestions for technological or strategic situations which would or would not make orbit-to-land operations (read: planetary invasions) unnecessary or obsolete, which were all quite interesting.

What I found most striking though was a relative confidence in how space battles would be waged in general, which I’ve seen both a little bit here in the comments and frequently more broadly in the hard-sci-fi community. The assumptions run very roughly that, without some form of magic-tech (like shields), space battles would be fought at extreme range, with devastating hyper-accurate weapons against which there could be no real defense, leading to relatively “thin-skinned” spacecraft. Evasion is typically dismissed as a possibility and with it smaller craft (like fighters) with potentially more favorable thrust-to-mass ratios. It’s actually handy for encapsulating this view of space combat that The Expanse essentially reproduces this model.

And, to be clear, I am not suggesting that this vision of future combat is wrong in any particular way. It may be right! But I find the relative confidence with which this model is often offered as more than a little bit misleading. The problem isn’t the model; it’s the false certainty with which it gets presented.

[…]

Coming back around to spaceships: if multiple national navies stocked with dozens of experts with decades of experience and training aren’t fully confident they know what a naval war in 2035 will look like, I find myself with sincere doubts that science fiction writers who are at best amateur engineers and military theorists have a good sense of what warfare in 2350 (much less the Grim Darkness of the Future Where There is Only War) will look like. This isn’t to trash on any given science fiction property mind you. At best, what someone right now can do is essentially game out, flow-chart style, probable fighting systems based on plausible technological systems, understanding that even small changes can radically change the picture. For just one example, consider the question “at what range can one space warship resolve an accurate target solution against another with the stealth systems and electronics warfare available?” Different answers to that question, predicated on different sensor, weapons and electronics warfare capabilities produce wildly different combat systems.

(As an aside: I am sure someone is already dashing down in the comments preparing to write “there is no stealth in space“. To a degree, that is true – the kind of Star Trek-esque cloaking device of complete invisibility is impossible in space, because a ship’s waste heat has to go somewhere and that is going to make the craft detectable. But detectable and detected are not the same: the sky is big, there are lots of sources of electromagnetic radiation in it. There are as yet undiscovered large asteroids in the solar-system; the idea of a ship designed to radiate waste heat away from enemies and pretend to be one more undocumented large rock (or escape notice entirely, since an enemy may not be able to track everything in the sky) long enough to escape detection or close to ideal range doesn’t seem outlandish to me. Likewise, once detected, the idea of a ship using something like chaff to introduce just enough noise into an opponent’s targeting system so that they can’t determine velocity and heading with enough precision to put a hit on target at 100,000 miles away doesn’t seem insane either. Or none of that might work, leading to extreme-range exchanges. Again, the question is all about the interaction of detection, targeting and counter-measure technology, which we can’t really predict at all.)

And that uncertainty attaches to almost every sort of technological interaction. Sensors and targeting against electronics warfare and stealth, but also missiles and projectiles against point-defense and CIWS, or any kind of weapon against armor (there is often an assumption, for instance, that armor is entirely useless against nuclear strikes, which is not the case) and on and on. Layered on top of that is what future technologies will even prove practical – if heat dissipation problems for lasers or capacitor limitations on railguns be solved problems, for instance. If we can’t quite be sure how known technologies will interact in an environment (our own planet’s seas) that we are intimately familiar with, we should be careful expressing confidence about how future technology will work in space. Consequently, while a science fiction setting can certainly generate a plausible model of future space combat, I think the certainty with which those models and their assumptions are sometimes presented is misplaced.

Bret Devereaux, “Fireside Friday: August 14th, 2020”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-08-14.

September 2, 2021

Charles Stross predicts that Elon Musk will become a multi-trillionaire

Charles Stross isn’t exactly a fan of Musk’s, but he outlines why he thinks Musk is on a potentially multi-trillion dollar path:

So, I’m going to talk about Elon Musk again, everybody’s least favourite eccentric billionaire asshole and poster child for the Thomas Edison effect — get out in front of a bunch of faceless, hard-working engineers and wave that orchestra conductor’s baton, while providing direction. Because I think he may be on course to become a multi-trillionaire — and it has nothing to do with cryptocurrency, NFTs, or colonizing Mars.

This we know: Musk has goals (some of them risible, some of them much more pragmatic), and within the limits of his world-view — I’m pretty sure he grew up reading the same right-wing near-future American SF yarns as me — he’s fairly predictable. Reportedly he sat down some time around 2000 and made a list of the challenges facing humanity within his anticipated lifetime: roll out solar power, get cars off gasoline, colonize Mars, it’s all there. Emperor of Mars is merely his most-publicized, most outrageous end goal. Everything then feeds into achieving the means to get there. But there are lots of sunk costs to pay for: getting to Mars ain’t cheap, and he can’t count on a government paying his bills (well, not every time). So each step needs to cover its costs.

What will pay for Starship, the mammoth actually-getting-ready-to-fly vehicle that was originally called the “Mars Colony Transporter”?

Starship is gargantuan. Fully fuelled on the pad it will weigh 5000 tons. In fully reusable mode it can put 100-150 tons of cargo into orbit — significantly more than a Saturn V or an Energiya, previously the largest launchers ever built. In expendable mode it can lift 250 tons, more than half the mass of the ISS, which was assembled over 20 years from a seemingly endless series of launches of 10-20 ton modules.

Seemingly even crazier, the Starship system is designed for one hour flight turnaround times, comparable to a refueling stop for a long-haul airliner. The mechazilla tower designed to catch descending stages in the last moments of flight and re-stack them on the pad is quite without precedent in the space sector, and yet they’re prototyping the thing. Why would you even do that? Well, it makes no sense if you’re still thinking of this in traditional space launch terms, so let’s stop doing that. Instead it seems to me that SpaceX are trying to achieve something unprecedented with Starship. If it works …

There are no commercial payloads that require a launcher in the 100 ton class, and precious few science missions. Currently the only clear-cut mission is Starship HLS, which NASA are drooling for — a derivative of Starship optimized for transporting cargo and crew to the Moon. (It loses the aerodynamic fins and the heat shield, because it’s not coming back to Earth: it gets other modifications to turn it into a Moon truck with a payload in the 100-200 ton range, which is what you need if you’re serious about running a Moon base on the scale of McMurdo station.)

Musk has trailed using early Starship flights to lift Starlink clusters — upgrading from the 60 satellites a Falcon 9 can deliver to something over 200 in one shot. But that’s a very limited market

As they say, read the whole thing.

July 25, 2021

The Line editors clearly loved crafting their “Dicks in space!” headline

As a fellow space nerd, I welcome the editors of The Line to our number:

You’ve probably noticed by now that your Line editors are space enthusiasts. It’s been an interesting few weeks on that front. Sir Richard Branson flew out of the atmosphere, into free-fall (not zero-G, you scientific illiterates!), on a Virgin Galactic space plane. That said, he didn’t get high enough to cross the Kármán line, which, in the absence of any real international agreement on where the Earth ends and space begins, is as close as we come to a functional definition of the edge of space. (It’s an altitude of 100 km, for those wondering.) Jeff Bezos, of Amazon wealth and fame, did cross that line this week, along with three passengers, including Wally Funk, which was cool, if you’re into that sort of thing. (We are.) Bezos was riding a Blue Origin New Shepard rocket; Blue Origin is a company he founded and funded with his own gigantic wealth.

Look, let’s face facts — your Line editors are into space. We just are. But yeah, we agree that space policy is important enough and complicated enough to warrant debate. Reasonable people can have different views on this stuff. And we also agree that there are important debates to have about the accumulated wealth of billionaires, and the distorting effects that wealth can have on politics and society.

But unlike a bunch of ya’ll, we don’t get confused about a debate over income inequality and a debate over space travel. You can despise Bezos, Amazon and everything he’s done there, and still recognize that what he is doing on the space front is important. Everyone rolling their eyes at Bezos matching space flight capabilities that the Soviets and Americans achieved literally 60 years ago is allowing their desire to rack up some sweet Twitter likes with a snarky dunk blind themselves to the fact that Bezos (and Elon Musk’s SpaceX, which is way ahead of Blue Origin) aren’t just recreating earlier capabilities, they are massively improving on them.

So yeah, Blue Origin can now do what the Soviets and U.S. could do 60 years ago, but they’re doing it more safely, more efficiently and much, much more sustainably than national space agencies did. Reusability isn’t a frill, it’s a massive game-changer. And as much fun as it is to snort when these private-sector companies recreate an existing capability, do you really think they’re going to stop there?

Branson’s company could be written off as a tourism play for the affluent. Fair enough. Except that making space flight economically viable is the first step to ensuring that capability is both sustainable and more broadly accessible in the long run. Further, Bezos and especially Musk are inventing new and transformative space-flight capabilities. They are materially pushing back against the final frontier in ways that we simply have not before. It won’t matter unless we choose to do anything with these new capabilities, and your guess is as good as ours as to whether or not we will. But we could. That’s huge.

As huge as the gigantic dick-shaped rocket Bezos rode up. Yeah, yeah. We snorted, too. But, like, seriously, folks — making penis jokes about the shape of an object dictated by aerodynamic considerations isn’t quite as witty as you think: the rockets are shaped like penises because they literally have to be in order to work. Having a giggle is fine, but if you actually think you’re making a real point about misogyny and fragile male egos when you get snippy (ahem) about a schlong-shaped rocket, well, we’d love to see what happens when your very emotionally vigorous and feminist vagina-shaped space vehicle hits max Q. So long as we aren’t aboard it or in the landing area for its hurtling debris.

Our main point still stands: don’t let your cynicism and even revulsion at these guys blind you to what they’re doing. Bezos isn’t gonna stop at Yuri Gagarin-vintage accomplishments. Musk sure hasn’t. This’ll matter. It’s time to get serious. They are.

December 14, 2019

History of Space Travel – Guided by Starlight – Extra History – #6

Extra Credits

Published 12 Dec 2019What happened after we touched down on the moon? And where are we going in the future? While we may have lost the glitz and glamor of the Space Race, we have continued to make incredible progress in reaching the stars. We’ve come together to build space stations while in space, create the international space station, and started developing new technologies that could take us to Mars and beyond.

Start your Warframe journey now and prepare to face your personal nemesis, the Kuva Lich — an enemy that only grows stronger with every defeat. Take down this deadly foe, then get ready to take flight in Empyrean! Coming soon! http://bit.ly/EHWarframe

December 7, 2019

History of Space Travel – One Small Step – Extra History – #5

Extra Credits

Published 5 Dec 2019Start your Warframe journey now and prepare to face your personal nemesis, the Kuva Lich — an enemy that only grows stronger with every defeat. Take down this deadly foe, then get ready to take flight in Empyrean! Coming soon! http://bit.ly/EHWarframe

The United States was losing the space race. A number of unfortunate missteps and mistakes had hindered their progress. But the United States had also structured its space program entirely differently from the USSR. Instead of being helmed by the military, the National Aeronautics & Space Administration was created by Eisenhower with an emphasis on exploration and research. And in the end, the later but more advanced satellites will collect the data required a dream firmly placed in the American consciousness by JFK. A dream to place a man on the moon.

From the comments:

Extra Credits

19 hours ago

The plaque still gives me goosebumps in the best way possible. Hopefully one day we can live up to its promise of peace. Be good to one another. ❤️And thanks to Rebecca Ford (the voice of Lotus) for voicing space mom at the end of each of these episodes. They’ve been a blast to make and we hope that you all have enjoyed this trip to the stars.

November 29, 2019

History of Space Travel – Red Star – Extra History – #4

Extra Credits

Published 28 Nov 2019Start your Warframe journey now and prepare to face your personal nemesis, the Kuva Lich — an enemy that only grows stronger with every defeat. Take down this deadly foe, then get ready to take flight in Empyrean! Coming soon! http://bit.ly/EHWarframe

While rockets had been proven to be indispensable to the Second World War, the idea to send people up into orbit was still seen as fantasy. Space was important only as a method to further the range of missiles meant to land oceans away from their original launch point. But a man named Korolev will change all of that, with work so secretive, he will be referred to as Chief Designer for nearly his entire life. But we all know the name of his first project into space: Sputnik.

From the comments:

Extra Credits

1 day ago

We weren’t able to fit her into the episode, but the other famous first cosmonaut in space is Laika, the Soviet space dog. She was a stray who was taken in by the program to test the Sputnik 2 and some of its life support features (like a coolant fan). Unfortunately, Laika did not return from her mission alive but she’s still regarded highly in the history of space flight and has become a symbol for the space race and animal testing in general. Look her up!

I remember reading in Robert Heinlein’s Expanded Universe of the day on his tour of the Soviet Union in 1960 when he and his wife were told by a group of Red Army cadets of a Soviet rocket launch carrying a human into orbit for the first time. The story was officially denied and the capsule was said to be unmanned after all. Wikipedia says:

According to Gagarin’s biography, these rumours were likely started as a result of two Vostok missions equipped with dummies (Ivan Ivanovich) and human voice tape recordings (to test if the radio worked) that were made just prior to Gagarin’s flight.

In a U.S. press conference on February 23, 1962, colonel Barney Oldfield revealed that an uncrewed space capsule had indeed been orbiting the Earth since 1960, as it had become jammed into its booster rocket. According to the NASA NSSDC Master Catalog, Korabl Sputnik 1, designated at the time 1KP or Vostok 1P, did launch on May 15, 1960 (one year before Gagarin). It was a prototype of the later Zenit and Vostok launch vehicles. The onboard TDU (Braking Engine Unit) had ordered the retrorockets to fire to recover, but due to a malfunction of the attitude control system, the spacecraft was oriented upside-down, and the firing put the craft into a higher orbit. The re-entry capsule lacked a heat shield as there were no plans to recover it. Engineers had planned to use the vessel’s telemetry data to determine if the guidance system had functioned correctly, so recovery was unnecessary.

November 6, 2019

How Did The Saturn 5 Rocket Work? | James May: On The Moon | Earth Lab

BBC Earth Lab

Published 3 Jan 2017James May meets Harrison Schmitt, one of the last men to ride Saturn 5 and learns a bit about the science behind a rocket with six million components.

Taken From James May: On the Moon

Welcome to BBC Earth Lab! Here we answer all your curious questions about science in the world around you (and further afield too). If there’s a question you have that we haven’t yet answered let us know in the comments on any of our videos and it could be answered by one of our Earth Lab experts.

June 26, 2019

“… what’s happening now is even better than Apollo”

At Popular Mechanics, Joe Pappalardo reminds us that the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 lunar landing is coming up next month, but that current developments in space are worth celebrating too:

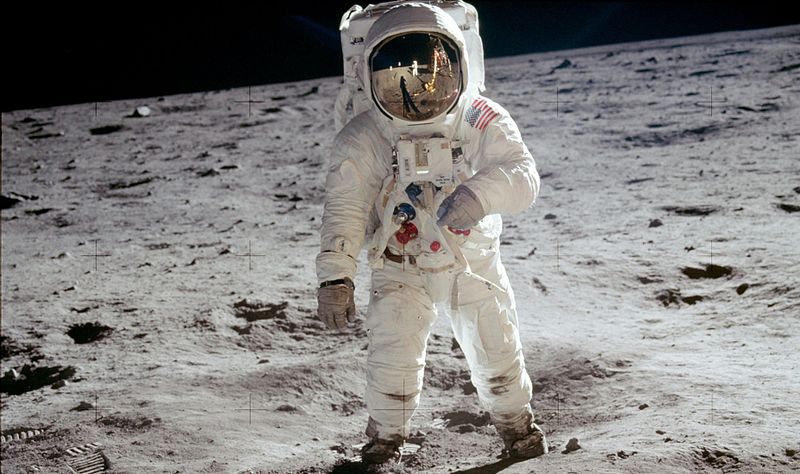

Astronaut Buzz Aldrin, lunar module pilot, stands on the surface of the moon near the leg of the lunar module, Eagle, during the Apollo 11 moonwalk. Astronaut Neil Armstrong, mission commander, took this photograph with a 70mm lunar surface camera. While Armstrong and Aldrin descended in the lunar module to explore the Sea of Tranquility, astronaut Michael Collins, command module pilot, remained in lunar orbit with the Command and Service Module, Columbia.

Apollo was born of Cold War desperation: a political exercise that paid enormous scientific and technological dividends. After the launch of Sputnik in 1957, it became vital to beat the Soviet Union to the Moon, a geopolitical urge that created an enormous budgetary effort.

The problem with politically motivated — well, anything — is that the faucet of support can be closed just as quickly as it opened. It happened to Apollo, as follow on missions were cancelled and the focus shifted to a reusable craft to service low-earth orbit. This pattern of shifting space priorities and strategies whipsawed NASA, most noticeably when the Obama administration’s cancellation of the Bush-era Constellation moon program in 2010.

But multiple private companies pursuing their niches in space have an obvious redundancy. While companies may rise and fall, the very nature of a commercial effort isn’t as dependent on government funding. If it’s worth doing, especially if it makes money, space industry will endure political shifts. The objectives of a well-run company do not change that much every four years.

That leaves today’s NASA with a choice: Do it themselves and control everything (the traditional way), or fund private companies to develop the tech the agency needs and then allow them to sell their services to any nation, company, or individual (the new way). With those services on the open market, NASA would be one of many customers for a new U.S.-based space economy.

This debate is boiling over right now. The ongoing effort to return to the moon, called Artemis (after Apollo’s sister), is becoming a lesson in the advantages of the commercial model.

[…]

If only investment guaranteed results. For those who miss bloated, government-run spaceflight, there is already a NASA spacecraft mired in the old ways of thinking. The feds have sunk a lot of money into the Space Launch System, a mega-rocket built to NASA specs for deep space missions. It was supposed to fly in 2017, but we’ll be lucky to see a first flight in 2020 — and it busted the $9.7 billion estimated budget, now costing about $12 billion.

But something happened during these SLS delays: the commercial space industry started delivering on its promises. Most visibly, private firms have been delivering supplies to the International Space Station for years and (hopefully soon) will ferry astronauts as well. Blue Origin and SpaceX has started development of crewed spacecraft able to reach to the moon and Mars. Elon Musk even sold a moon trip to a Japanese billionaire.

May 2, 2019

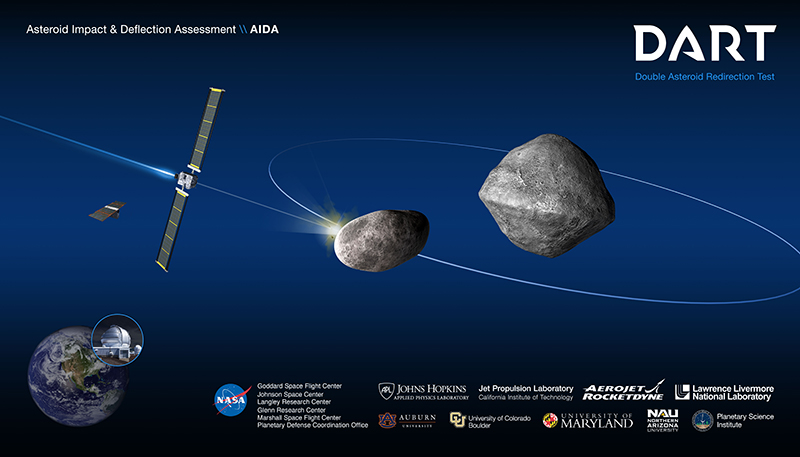

NASA to export bullying off the Earth to small, harmless objects in the solar system

Colby Cosh on NASA’s latest plan for “nudging” an asteroid out of its orbit:

NASA has a plan — a serious plan, which it intends to carry out pretty soon — to smash a spacecraft into an object in the solar system and intentionally change its orbit. I confess I don’t quite know why this act of awesome American techno-hubris hasn’t been bigger news. I think partly it is because the mission comes under the heading of “planetary defence” against small natural objects straying into the path of the Earth. Science reporters on that beat are easily distracted by apocalyptic fantasies, and by smirking anthropology about the actually-quite-numerous band of researchers trying to deal with this arguably-quite-important subject.

Part of the problem may be that NASA’s mission to mess with the asteroid Didymos B is hidden under a mountain of technical jargon about “kinetic impactors” and “xenon thrusters.” And part of it is surely the hard-earned professional knowledge that NASA ends up implementing about one plan for every 10 it makes. Accountants have a way of showing up with an axe at the last minute.

Still, the idea is pretty neat, and not just because it appeals to everyone’s natural appetite for destruction. The basic premise of the DART (Double Asteroid Redirection Test) is that our planet may one day face the asteroid/meteor/comet collision scenario outlined in a vast corpus of books and movies (Lucifer’s Hammer, Armageddon, Deep Impact). If that day comes, we as a species don’t want to just be winging it — so let’s go out now, find some innocent chunk of rock that isn’t bothering anybody, and see if we already have the technological capability to change its course.

This turns out not to necessarily involve Bruce Willis or Robert Duvall; mostly we just need Isaac Newton. The scheme of planetary defence now emerging from decades of speculation and effort emphasizes systematic tracking of near-Earth objects and early detection of potentially dangerous ones. If we can spot an approaching impactor soon enough, we don’t need to deliver a bundle of explosives: we can just nudge it out of the way.

Humanity has been pretty lucky that the asteroid impacts have been relatively rare since we started keeping track of important things like the planting calendar, the seasonal flooding of the rivers, and the ever-important (to the rulers) tax records. It wouldn’t take a particularly large object hurtling into the atmosphere at interplanetary speeds to ruin our collective day (year, decade, century, etc.). We think we know how to divert incoming dangerous objects … but we need to actually do it successfully before it becomes the last headline of all recorded history.

April 30, 2019

You Will Never Do Anything Remarkable

exurb1a

Published on 28 Apr 2019Illegitimi non carborundum, yo.

So.

The original line was, “If they give you ruled paper, write the other way.” As far as I can tell it’s Juan Ramón Jiménez’s.I am also now painfully aware I’ve written a half as ‘2/1’. Sorry maths.

Please note that this wasn’t intended to be a diatribe against critics or experts. They obviously play an important role. It was more directed at the recreational cynicism one comes across in daily life from time to time, generally pointed at young artists. I have had the privilege to meet plenty of people 1000x more talented than me, who are simultaneously doubting their abilities because of some stupid comment made by an unpleasant teacher or jaded family member.

If you are that artist, I really just wanted to say: You’re in good company; the Greats doubted themselves too. Don’t let the bastards get you down and I hope you make all manner of interesting and fantastic things.

The music is the 3rd movement of Big Baus Brahms’ Violin Concerto in D Major: https://youtu.be/Ev45Knhdlp8

I like that piece lots. I hope you do too.

Again, all the very best of luck in your projects.

February 10, 2018

When cinematography wins out over reality

Earlier this month, Charles Stross talked about why he’s been reading less and less science fiction lately, and touched on SF movies and (for example) why George Lucas chose to model space combat on World War 1 aircraft battles:

When George Lucas was choreographing the dogfights in Star Wars, he took his visual references from film of first world war dogfights over the trenches in western Europe. With aircraft flying at 100-200 km/h in large formations, the cinema screen could frame multiple aircraft maneuvering in proximity, close enough to be visually distinguishable. The second world war wasn’t cinematic: with aircraft engaging at speeds of 400-800 km/h, the cinematographer would have had a choice between framing dots dancing in the distance, or zooming in on one or two aircraft. (While some movies depict second world war air engagements, they’re not visually captivating: either you see multiple aircraft cruising in close formation, or a sudden flash of disruptive motion — see for example the bomber formation in Memphis Belle, or the final attack on the U-boat pen in Das Boot.) Trying to accurately depict an engagement between modern jet fighters, with missiles launched from beyond visual range and a knife-fight with guns takes place in a fraction of a second at a range of multiple kilometres, is cinematically futile: the required visual context of a battle between massed forces evaporates in front of the camera … which is why in Independence Day we see vast formations of F/A-18s (a supersonic jet) maneuvering as if they’re Sopwith Camels. (You can take that movie as a perfect example of the triumph of spectacle over plausibility at just about every level.)

… So for a couple of generations now, the generic vision of a space battle is modelled on an air battle, and not just any air battle, but one plucked from a very specific period that was compatible with a film director’s desire to show massed fighter-on-fighter action at close enough range that the audience could identify the good guys and bad guys by eye.

Let me have another go at George Lucas (I’m sure if he feels picked on he can sob himself to sleep on a mattress stuffed with $500 bills). Take the asteroid field scene from The Empire Strikes Back: here in the real world, we know that the average distance between asteroids over 1km in diameter in the asteroid belt is on the order of 3 million kilometers, or about eight times the distance between the Earth and the Moon. This is of course utterly useless to a storyteller who wants an exciting game of hide-and-seek: so Lucas ignored it to give us an exciting game of …

Unfortunately, we get this regurgitated in one goddamned space opera after another: spectacle in place of insight, decolorized and pixellated by authors who haven’t bothered to re-think their assumptions and instead simply cut and paste Lucas’s cinematic vision. Let me say it here: when you fuck with the underlying consistency of your universe, you are cheating your readers. You may think that this isn’t actually central to your work: you’re trying to tell a story about human relationships, why get worked up about the average spacing of asteroids when the real purpose of the asteroid belt is to give your protagonists a tense situation to survive and a shared experience to bond over? But the effects of internal inconsistency are insidious. If you play fast and loose with distance and time scale factors, then you undermine travel times. If your travel times are rubberized, you implicitly kneecapped the economics of trade in your futurescape. Which in turn affects your protagonist’s lifestyle, caste, trade, job, and social context. And, thereby, their human, emotional relationships. The people you’re writing the story of live in a (metaphorical) house the size of a galaxy. Undermine part of the foundations and the rest of the house of cards is liable to crumble, crushing your characters under a burden of inconsistencies. (And if you wanted that goddamn Lucasian asteroid belt experience why not set your story aboard a sailing ship trying to avoid running aground in a storm? Where the scale factor fits.)

Whatever you do, don’t go asking him about Han Solo’s claimed Kessel Run in less than 12 parsecs…