I almost skipped reading this one, as Matt and Jen usually keep their own columns behind the paywall, but this one is free to non-paying cheapskates like me:

… I actually think there is one way that Hollywood — and probably mass entertainment writ large — has kind of warped our society. It’s not that it has promoted degeneracy or loose morals or shameless enjoyment of vice. It’s more insidious. And probably more dangerous.

I think Hollywood has tricked us into thinking that, in an emergency, our governments will prove to be a lot more competent than they will be. And usually are.

This is something I’ve been thinking about for a while. I’ve mentioned it to my Line colleagues before, and I call it my Hollywood Thesis. As I see it, the broader public has fairly accurate expectations about the level of service they can expect from their government. Sometimes it’s good, sometimes it’s bad, but it’s mostly realistic. We basically know what we’re getting into when we, for example, drag the trash bin to the curb, or turn on a tap in the morning, or go to an emergency room because you need to get stitched up after a minor mishap.

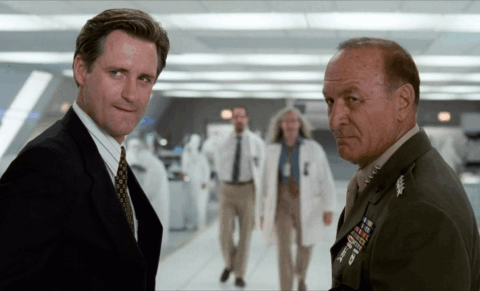

But I’ve observed over the years an interesting exception. When the public is confronted with any kind of new or unexpected threat, people, for some reason, believe their government will have some secret ability or unexpected expertise in dealing with it. Maybe it’s a quirky scientist working in the bowels of some ministry or department. Maybe it’s an elite team of experts. Or some hidden base loaded with commandos and advanced weaponry.

Wrong. And I’ve been thinking about this. Why do we assume the same government that is, for instance, struggling to fill potholes in my city, or hire enough nurses in my province, or fix a federal payroll system, is going to be more competent when presented with something totally out of the blue? This flies in the face of all of our lived experiences with government. It’s a generous assumption of state capacity that is, to put it charitably, unearned.

So why? What explains this?

It’s Hollywood. It has to be.

Lots of smart, competent people have government jobs. One of the great joys of my career has been the opportunity to speak with many. There are shining lights of unusual competency in every department, and at every order of government, really — my colleague Jen Gerson recently told our podcast listeners about how one of these hidden gems helped her cut through a confusing and dysfunctional process so she could get a permit. And I will never get tired of saying good things about the men and women of the Canadian Armed Forces — true miracle workers we do not support enough.

But there aren’t hidden capabilities. There aren’t secret teams. The same people trying to prevent Canada Post from going on strike will be the same people handling the next pandemic — or who would be responsible for opening a dialogue if aliens decided to land their mothership in the middle of a Saskatchewan farm.

It’s within the range of possibilities that, presented with a unique challenge, government leaders could rise to meet it … as long as it’s a completely unexpected situation with no pre-existing rules or regulations or bureaucratic processes in place. I admit it’s not the way the smart money would bet, but it’s technically a possibility.