Ted Gioia met with a group of executives from movie distribution firms outside the North American market back in 2016. It was a good time, financially, but the overall tone of the meeting was anxious because the trend seemed unsustainable:

These were smart people, but they didn’t make the movies. They just ran theater chains. But they didn’t need to be specialists in creativity or storytelling to know that hit films were now built on tired formulas, the same plot lines played out over and over again.

Special effects added some sizzle to the steak, but it was still the same stale meal night after night. Sooner or later, even superheroes die.

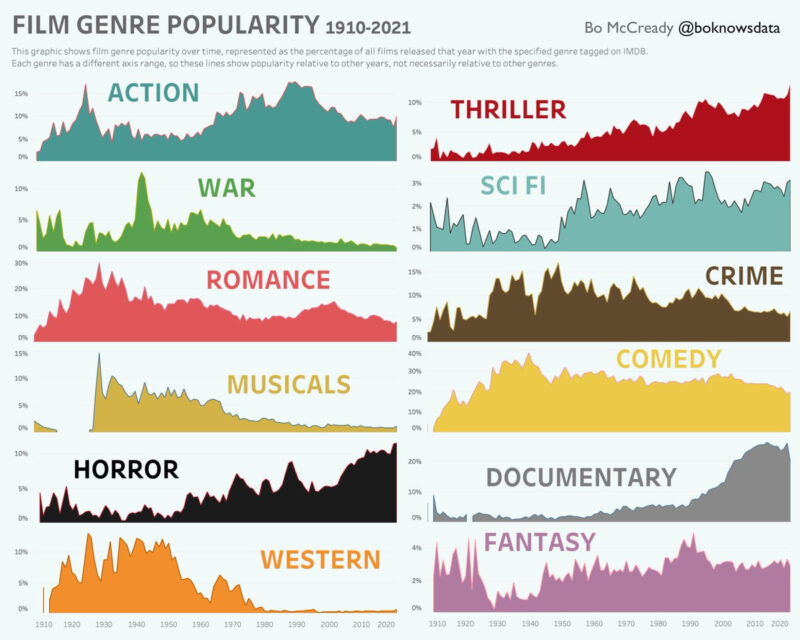

Other genres have come and gone — westerns and musicals and other box office draws of the past. Comic book franchises would eventually meet the same fate.

Source: Bo McReady

Back then, Disney was bragging to shareholders that another 20 Marvel films were already in the pipeline. And that was just a start. CEO Bob Iger explained that Disney owned the rights to 7,000 different Marvel characters — implying that brand franchises could propagate forever, like copulating Australian bunnies.

That was the party line in Burbank. But most of the people I spoke to that day privately expressed doubts about this formula-driven strategy. They hoped to enjoy a few more years of boom times, but worried about what would happen next.

“It takes a special kind of stupid to kill off Indiana Jones or Toy Story or a Marvel superhero, but that’s exactly what’s playing out right now in the Magic Kingdom.”

As it turned out, they were right to worry. But a virus, not a superhero, let them down. The first COVID case happened almost exactly three years after my December 2016 talk.

But it now looks like the pandemic merely delayed the creative collapse.

Hollywood has saturated the market with look-alike movies. Their pipeline of films is now exploding like the Nord Stream, but with this difference—studios are still sitting on a huge pile of future bombs.

And what does a studio do with a bomb on its hands?

They have four options—and they are four kinds of ugly

- You delay the film, hoping for a better market environment in the future.

- You send it back for rewriting and more filming

- You cancel it entirely, and write off the investment

- You release it — sinking another $50 million, more or less, into marketing — and then watch it collapse at the box office.

Disney is getting a sour taste of strategy number four this week.