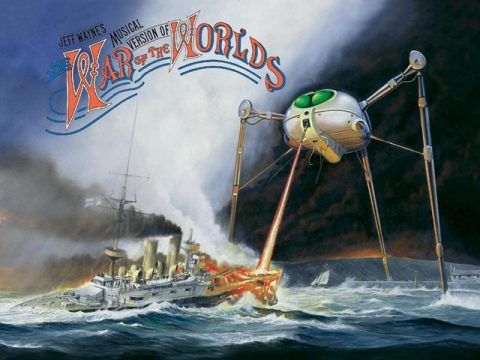

Apparently “the Artilleryman” from Jeff Wayne’s musical interpretation of War of the Worlds has taken over some important post at Oxford:

The Classics Faculty at the University of Oxford is considering whether to remove from its undergraduate courses the compulsory study in their original languages of Homer and Vergil. The reasons given are that students from independent schools, where some classical teaching is kept up, tend at the moment to do better in examinations than students from state schools, and that men do better than women. I regard this as the most important news of the week. I do so partly because I make some of my living from these languages, and so have a financial interest in their survival. I do so mainly because I see the proposal as a further enemy advance in the Culture War through which we have been living for at least the past two generations.

I could make this essay into another attack on the cultural leftists. I will come to these, as they are among the villains. They are not, however, the main villains. These are people who sometimes regard themselves, and are generally regarded by others, as conservatives. They once looked to Margaret Thatcher as their political champion, and then to Tony Blair. They were some of the most committed advocates of our departure from the European Union. They now look to the Johnson Government for the final triumph of their agenda. For these people, a nation is barely more than a giant economic enterprise – Great Britain plc. For them, the main, or perhaps the sole, purpose of education is to provide sets of skills that have measurable value in a corporatised market.

These people have been around for a long time. They were satirised by Charles Dickens in Hard Times, where Thomas Gradgrind explains his philosophy of education:

Now, what I want is, Facts. Teach these boys and girls nothing but Facts. Facts alone are wanted in life. Plant nothing else, and root out everything else. You can only form the minds of reasoning animals upon Facts: nothing else will ever be of any service to them. This is the principle on which I bring up my own children, and this is the principle on which to bring up these children. Stick to Facts, sir!

[…]

I agree that state education had become a joke where almost nothing of any kind was taught. As continued by Tony Blair, the Thatcher reforms did eventually drive up standards of literacy and numeracy. But this has been at a terrible cost. Any modern school that wants to be thought desirable must focus on its place in the league tables. This involves working the children like slaves – stuffing them in class with facts that can be regurgitated in tests and therefore graded, then handing out reams of homework that leaves no time for personal development.

The universities continue this conveyor belt approach. Around half of school leavers are pressured into “higher” education. Those who go into the “STEM” subjects – Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics – follow a narrow and specialised curriculum that leaves them ignorant of nearly everything outside their own subject. The rest sign up for largely worthless subjects – anything with the words “business” or “studies” in the name. There, they are kept busy with three-hour lectures. I know the value of these, as I used to give them. I fell asleep in one of them, and the students were happy when my voice finally trailed off. Progress in these subjects is measured by coursework that is increasingly plagiarised or ghost-written, or through examinations where the grades are fiddled. At the end of this, graduates – and everyone does graduate – are qualified for nothing better than employment in one of those bureaucracies of management or control that fasten on the actually productive like mistletoe on a tree. The universities look at rising numbers and the fact that graduates do find paid employment, and call this a great success. No one thinks it a disgrace if students never take up a book not on their worthless reading list, or that, having graduated, they never open another book.

Or school leavers at the bottom end are herded into courses in plumbing or hairdressing. I was once invited to teach a module in a Parking Studies degree – this for the certification of traffic wardens. I suppose people are needed to keep the roads clear, and I suppose they should be given some idea of their legal rights and duties. I am not at all sure if they need to have degrees. I am sure that skilled trades of undoubted value are best taught, as they always used to be, through private apprenticeships or informally on the job.