The History Guy: History Deserves to Be Remembered

Published 8 Dec 2021December 7, 1941 is remembered as the date that will live in infamy, but that term was spoken by President Franklin Roosevelt on December 8th. Nowhere was the weight of history more obvious than in the territory of Hawaii.

(more…)

December 7, 2024

Aftermath: December 8

December 4, 2024

Admirals belatedly realize it might be useful to be able to reload those fancy missiles at sea

CDR Salamander has been banging this drum for a long, long time, but it appears that the US Navy is finally acknowledging that being able to reload the (many) Vertical Launch System (VLS) missile cells on ships somewhere other than a fully functional naval base would be more than a nice-to-have capability:

Reloading a VLS cell on a US Navy ship in port.

Photo attributed to defunct website defense-aerospace.com.

If you have made the horrible error of not reading every post here, over at the OG Blog and listening to every Midrats, then you may be new to the issue of being able to reload our warships’ VLS cells forward.

Slowly … a bit too slowly … Big Navy has decided that those people in the 1970s (who still remembered fighting a contested war at sea) might have been right all along. With SECNAV Del Toro’s encouragement, we continue to try to find a way to get the surface force a capability to reload forward.

There is plenty of room on the bandwagon and we’re glad to hoist everyone onboard the reload/rearm party-bus. If you need to catch up, the issue continues to break above the background noise, and WSJ has a very well produced article on it that requires your attention.

However, I got a little bit of an eye twitch at this pull-quote:

Until recently, the Navy didn’t feel much need for speed in rearming its biggest missile-firing warships. They only occasionally launched large numbers of Tomahawk cruise missiles or other pricey projectiles.

Now, Pentagon strategists worry that if fighting broke out in the western Pacific — potentially 5,000 miles from a secure Navy base — destroyers, cruisers and other big warships would run out of vital ammunition within days, or maybe hours.

Seeking to plug that supply gap, Del Toro tasked commanders and engineers with finding ways to reload the fleet’s launch systems at remote ports or even on the high seas. Otherwise, U.S. ships might need to sail back to bases in Hawaii or California to do so — putting them out of action for weeks.

Yes, I am going to do this, and you’re coming along for the ride.

In the name of great Neptune’s trident … THIS IS NOT A NEW REQUIREMENT!!!

My first “… shit, we need to be able to do this …” was during the DESERT FOX strikes against Iraq in 1998. I cannot remember if it were USS Stout (DDG 55) or USS Gonzalez (DDG 66) that we put Winchester on TLAM by the third day … but except for the ships we left on the other side of the Suez (who we would put to good use later), the rest of our TLAM ships and submarines were about done.

The fact we threw away an ability to reload/rearm forward was an old story inside the surface Navy when I picked it up in the last years of the previous century. We had a clunky erector set like contraption that was hard to use and took up VLS cell space, but instead of finding a better way, we just chunked the whole idea, slid in our Jesus Jones CD, and figured we had ownership of the seas until the crack of doom.

There is nothing “until recently” about this. Not to get off topic, but the real story here is why time and again this century’s senior leadership decided it was “too hard” or “too dangerous” while they were in full knowledge not just of the operational experience demanding this capability, but what we discovered over and over again in wargames.

December 2, 2024

USS Constitution – “Old Ironsides” – 1950’s newsreel

Charlie Dean Archives

Published Jan 1, 2014USS Constitution is a wooden-hulled, three-masted heavy frigate of the United States Navy. Named by President George Washington after the Constitution of the United States of America, she is the world’s oldest floating commissioned naval vessel. Launched in 1797, Constitution was one of six original frigates authorized for construction by the Naval Act of 1794. Joshua Humphreys designed the frigates to be the young Navy’s capital ships, and so Constitution and her sisters were larger and more heavily armed and built than standard frigates of the period. Built in Boston, Massachusetts at Edmund Hartt’s shipyard, her first duties with the newly formed United States Navy were to provide protection for American merchant shipping during the Quasi-War with France and to defeat the Barbary pirates in the First Barbary War.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Cons…

CharlieDeanArchives – Archive footage from the 20th century making history come alive!

November 13, 2024

Anglo-German Dreadnought Arms Race – Anything you can build I can build better!

Drachinifel

Published Nov 17, 2021Today we take a whistlestop tour behind the driving forces and outcome of the Anglo-German Naval Arms Race that led up to WW1.

November 11, 2024

In memoriam

A simple recognition of some of our family members who served in the First and Second World Wars:

The Great War

Private William Penman, Scots Guards, died 16 May, 1915 at Le Touret, age 25

Private William Penman, Scots Guards, died 16 May, 1915 at Le Touret, age 25

(Elizabeth’s great uncle)- Private Archibald Turner Mulholland, Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders, mortally wounded 25 September, 1915 at Loos, age 27

(Elizabeth’s great uncle) - Private David Buller, Highland Light Infantry, died 21 October, 1915 at Loos, age 35

(Elizabeth’s great grandfather) - Private Harold Edgar Brand, East Yorkshire Regiment. died 4 June, 1917 at Tournai.

(My first cousin, three times removed) - Private Walter Porteous, Durham Light Infantry, died 4 October, 1917 at Passchendaele, age 18

(my great uncle, who had married the day before he left for the front and never returned) - Corporal John Mulholland, Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders, wounded 2 September, 1914 (shortly before the First Battle of the Aisne), wounded again 29 June, 1918, lived through the war.

(Elizabeth’s great uncle) - John Eleazar (“Ellar”) Thornton, (ranks and dates of service unknown, served in the Royal Garrison Artillery, the East Surrey Regiment, and the Essex Regiment (dates of service unknown, but he likely joined the RGA in 1899). Put on the “Z” list after the war — recall list. He died in an asylum in 1943.

(my grandfather’s eldest brother) - Henry (Harry) Thornton, (uncertain) Lancashire Fusiliers. (We are not sure it is him as there were no identifying family or birth date listed. Rejected for further service.)

(my grandfather’s second older brother)

The Second World War

- Flying Officer Richard Porteous, Royal Air Force, survived the defeat in Malaya, was evacuated to India and lived through the war.

(my great uncle) - Able Seaman John Penman, Royal Navy, served in the Defensively Equipped Merchant fleet on the Atlantic convoys, the Murmansk Run (we know he spent a winter in Russia at some point during the war) and other convoy routes, was involved in firefighting and rescue efforts during the Bombay Docks explosion in 1944, lived through the war.

(Elizabeth’s father. We received his Arctic Star medal in July, 2024.) - Private Archie Black (commissioned after the war and retired as a Major), Gordon Highlanders, captured during the fall of Singapore (aged 15) and survived a Japanese POW camp (he had begun to write an autobiography shortly before he died)

(Elizabeth’s uncle) - Elizabeth Buller, “Lumberjill” in the Women’s Timber Corps, an offshoot of the Women’s Land Army in Scotland through the war.

(Elizabeth’s mother) - Trooper Leslie Taplan Russon, 3rd Royal Tank Regiment, died at Tobruk, 19 December, 1942 (aged 23).

Leslie was my father’s first cousin, once removed (and therefore my first cousin, twice removed). - Reginald Thornton, rank and branch of service unknown, hospitalized during the war with shellshock and was never discharged back into civilian life. He died in York in 1986.

(my grandfather’s youngest brother)

My maternal grandfather, Matthew Kendrew Thornton, was in a reserved occupation during the war as a plater working at Smith’s Docks in Middlesbrough. The original design for the famous Flower-class corvettes came from Smith’s Docks and 16 of the 196 built in the UK during the war (more were built in Canada). My great-grandmother was an enthusiastic ARP warden through the war (she reportedly enjoyed enforcing blackout compliance in the neighbourhood using the rattle and whistle that came with the job).

For the curious, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission the Royal British Legion, and the Library and Archives Canada WW1 and WW2 records site provide search engines you can use to look up your family name. The RBL’s Every One Remembered site shows you everyone who died in the Great War in British or Empire service (Canadians, Australians, New Zealanders, South Africans and other Imperial countries). The CWGC site also includes those who died in the Second World War. Library and Archives Canada allows searches of the Canadian Expeditionary Force and the Royal Newfoundland Regiment for all who served during WW1, and including those who volunteered for the CEF but were not accepted.

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae, MD Canadian Army Medical Corps (1872-1918)

Here is Mark Knopfler’s wonderful song “Remembrance Day” from his Get Lucky album, set to a slideshow of British and Canadian images from World War I through to more recent conflicts put together by Bob Oldfield:

October 27, 2024

The Great Demobilization: How the Allied Armies Were Sent Home

World War Two

Published 26 Oct 2024After the war, the Allies face the new challenge how to bring home the tens of millions of troops they have deployed across the globe. Today Indy examines this massive logistical effort, looking at the American Operation Magic Carpet, the British government’s slow but steady approach, and the devastation that Soviet troops returned home to.

(more…)

October 22, 2024

A Conquering Hat: a History of the Bicorn

HatHistorian

Published Jul 1, 2022Emblematic of Napoleon Bonaparte and his age of conquest, the bicorn is a distinctive military hat that became part of the most formal of dress uniforms and remains to this day in certain ceremonial outfits

The bicorn I wear in this video comes from Theatr’Hall in Paris https://www.theatrhall.com. The uniform comes from thejacketshop.co.uk

Title sequence designed by Alexandre Mahler

am.design@live.comThis video was done for entertainment and educational purposes. No copyright infringement of any sort was intended.

September 18, 2024

The Korean War 013 – 70,000 UN Troops Head for Incheon – September 17, 1950

The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published 17 Sep 2024[NR: For some unknown reason, YT decided to restrict the original release of this video, so I’m replacing it with the “Censored” version posted a couple of days later.]

This week sees the UN forces execute Operation Chromite, the amphibious invasion of the port of Incheon, far behind enemy lines. There are many hurdles to clear before this can happen, including the physical one of one of the world’s largest tidal ranges, which leaves many kilometers of mud flats in the approaches. There is also a UN counterattack at the same time, designed to perhaps break out of the Pusan Perimeter, or at least tie down big chunks of the enemy in the south.

(more…)

August 24, 2024

Operation Downfall – the planned invasion of Japan in 1946

Wes O’Donnell talks about the thankfully never-launched invasion of the Japanese home islands at the end of the Second World War:

History often hinges on the narrowest of margins.

Entire nations can rise or fall based on decisions made under the pressures of the moment.

But what if those decisions had gone the other way?

What if Archduke Franz Ferdinand had survived the assassination attempt in 1914?

What if John F. Kennedy had lived to complete a second term?

And most intriguingly, what if the United States had not dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945?

The world would have witnessed Operation Downfall, the Allied invasion of Japan — an operation that, by all accounts, would have been the bloodiest amphibious assault in human history.

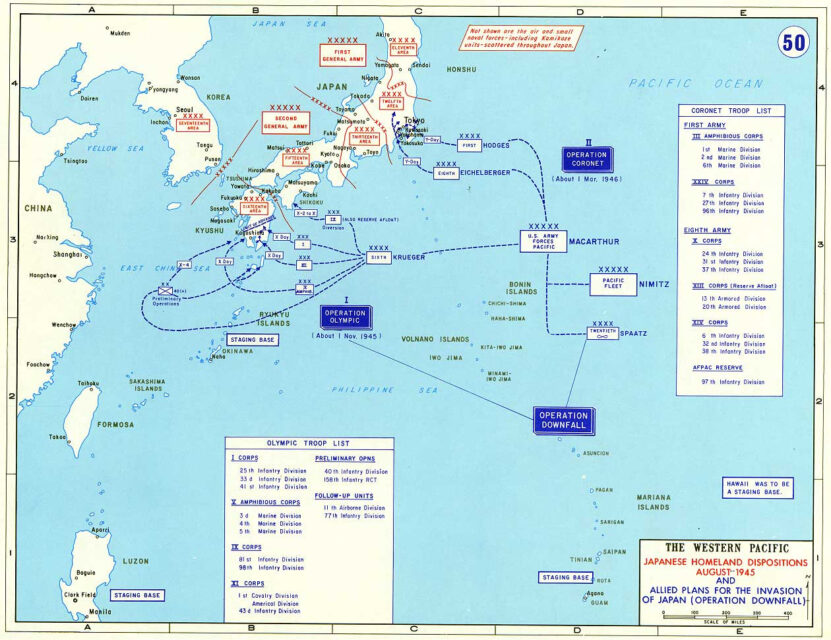

Operation Downfall was the codename for the proposed Allied plan for the invasion of Japan near the end of World War II.

The planned operation was abandoned when Japan surrendered following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Soviet declaration of war.

The operation had two parts: Operations Olympic and Coronet.

Set to begin in November 1945, Operation Olympic was intended to capture the southern third of the southernmost main Japanese island, Kyūshū, with the recently captured island of Okinawa to be used as a staging area.

Later, in the spring of 1946, Operation Coronet was the planned invasion of the Kantō Plain, near Tokyo, on the Japanese island of Honshu.

Airbases on Kyūshū captured in Operation Olympic would allow land-based air support for Operation Coronet.

The most troubling aspect of Downfall may have been the logistical problems facing military planners.

By 1945, there simply were not enough shipping, service troops, or engineers present to shorten the turnaround time for ships, connect the scattered installations across the Pacific, or build facilities like air bases, ports, and troop housing.

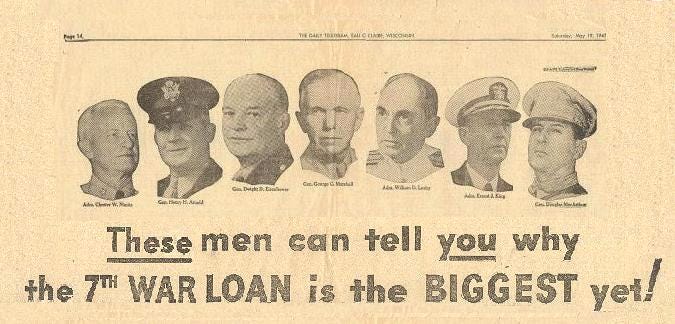

By this point in the war, the War Department had several military leaders that the government trusted to execute a quick end to hostilities.

Unlike the heavy political influence found in today’s wars, these men were given almost total freedom to plan large-scale military operations – Truman’s decision to drop the atomic bombs notwithstanding.

Six men of destiny

Responsibility for planning Operation Downfall fell to some of the most prominent American military leaders of the 20th century: Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz, General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff — Fleet Admirals Ernest King and William D. Leahy, along with Generals of the Army George Marshall and Hap Arnold, who commanded the U.S. Army Air Forces.

These six men, raised in the relatively stable and predictable world of late 19th-century small-town America, carried with them the values instilled by that era.

Arnold and MacArthur were West Point graduates; King, Leahy, and Nimitz came out of the Naval Academy; while Marshall honed his discipline at the Virginia Military Institute, a school renowned for its toughness, even more so than the service academies.

For these leaders, the concepts of duty, honor, and country were more than just words — they were guiding principles.

They approached their roles without a trace of cynicism, supremely confident in their ability and, crucially, their God-given right to steer the course of history, especially in the chaos of war.

August 19, 2024

The US Navy’s mis-managed decline continues

Niccolo Soldo from his weekend wrap-up of various news articles that caught his eye:

Artist’s rendering of the US Navy’s FFG(X) Constellation-class guided missile frigate. Initial contract awarded 30 April, 2020, but delivery of the first ship is not expected until 2029 due to design changes and other issues.

US Navy image via Wikimedia Commons.

One data point that works in favour of American Declinism is the US Navy’s inability to not just keep up with the Chinese in terms of the production of ships, but to also maintain its own production output. Many lightly-armed littoral combat ships have been retired, for example, with nothing to replace them.

These production setbacks have been pointed out to me, with one mutual on Twitter/X reiterating the point so that I get it (I do!). This is an actual problem that requires solving, and fast. It is partially to blame for the Americans effectively ceding the Red Sea to the Houthis (for now).

AP has done a partial deep-dive (horrible language here, I apologize) on this issue:

The labor shortage is one of myriad challenges that have led to backlogs in ship production and maintenance at a time when the Navy faces expanding global threats. Combined with shifting defense priorities, last-minute design changes and cost overruns, it has put the U.S. behind China in the number of ships at its disposal — and the gap is widening.

Navy shipbuilding is currently in “a terrible state” — the worst in a quarter century, says Eric Labs, a longtime naval analyst at the Congressional Budget Office. “I feel alarmed,” he said. “I don’t see a fast, easy way to get out of this problem. It’s taken us a long time to get into it.”

Marinette Marine is under contract to build six guided-missile frigates — the Navy’s newest surface warships — with options to build four more. But it only has enough workers to produce one frigate a year, according to Labs.

A lot of the guys who know how to do this work are retiring or have already retired. Sound familiar?

One of the industry’s chief problems is the struggle to hire and retain laborers for the challenging work of building new ships as graying veterans retire, taking decades of experience with them.

Shipyards across the country have created training academies and partnered with technical colleges to provide workers with the skills they need to construct high-tech warships. Submarine builders and the Navy formed an alliance to promote manufacturing careers, and shipyards are offering perks to retain workers once they’re hired.

Andreini trained for his job at Marinette through a program at Northeast Wisconsin Technical College. Prior to that, he spent several years as a production line welder, making components for garbage trucks. He said some of his buddies are held back by the stigma that shipbuilding is a “crappy work environment, and it’s unsafe.”

The problem:

Much of the blame for U.S. shipbuilding’s current woes lies with the Navy, which frequently changes requirements, requests upgrades and tweaks designs after shipbuilders have begun construction.

That’s seen in cost overruns, technological challenges and delays in the Navy’s newest aircraft carrier, the USS Ford; the spiking of a gun system for a stealth destroyer program after its rocket-assisted projectiles became too costly; and the early retirement of some of the Navy’s lightly armored littoral combat ships, which were prone to breaking down.

The Navy vowed to learn from those past lessons with the new frigates they are building at Marinette Marine. The frigates are prized because they’re less costly to produce than larger destroyers but have similar weapon systems.

Now check this out:

The Navy chose a ship design already in use by navies in France and Italy instead of starting from scratch. The idea was that 15% of the vessel would be updated to meet U.S. Navy specifications, while 85% would remain unchanged, reducing costs and speeding construction.

Instead, the opposite happened: The Navy redesigned 85% of the ship, resulting in cost increases and construction delays, said Bryan Clark, an analyst at the Washington-based think tank Hudson Institute. Construction of the first-in-class Constellation warship, which began in August 2022, is now three years behind schedule, with delivery pushed back to 2029.

The final design still isn’t completed.

Shifting threats:

Throughout its history, the Navy has had to adapt to varying perils, whether it be the Cold War of past decades or current threats including war in the Middle East, growing competition from Chinese and Russian navies, piracy off the coast of Somalia and persistent attacks on commercial ships by Houthi rebels in Yemen.

And that’s not all. The consolidation of shipyards and funding uncertainties have disrupted the cadence of ship construction and stymied long-term investments and planning, says Matthew Paxton of the Shipbuilders Council of America, a national trade association.

“We’ve been dealing with inconsistent shipbuilding plans for years,” Paxton said. “When we finally start ramping up, the Navy is shocked that we lost members of our workforce.”

How is the US Navy supposed to protect Taiwan from a potential Chinese invasion?

August 10, 2024

“Heavy casualties” in a modern western army might count as “a skirmish” in earlier conflicts

I sent a link to Severian a few weeks ago, thinking it might be an interesting topic for his audience and he posted a response as part of Friday’s mailbag post. First, my explanation to him about why I thought the link was interesting:

I know that Edward Luttwak is what the Brits call “a Marmite figure” … people love or hate him and not much in between. I’ve read several of his books and found he had interesting things to say about the Roman and Byzantine armies in their respective eras but I haven’t found his modern analysis to be anywhere near as interesting. This time, however, he might well have found that acorn … is the dramatic casualty-aversion of western nations going to be a key element of future, shall we say “adventurism”?

Clearly, [Vladimir Putin and Benjamin Netanyahu] can still get their legions moving when they feel they need to, but could [insert current US President here] get the 101st Airborne into a high-casualty environment (let’s not pretend that Rishi Sunak or Keir Starmer could or would, and Macron’s posturing is nearly as bad as Baby Trudeau’s total lack of seriousness)?

Anyway, here’s the Marmite Man’s latest – https://unherd.com/2024/06/who-will-win-a-post-heroic-war

Sev responded:

US Army soldiers assigned to 2-7 Cavalry, 2nd Brigade Combat Team (BCT),3rd battalion 1st Division, rush a wounded Soldier from Apache Troop to a waiting USMC CH-46E Sea Knight helicopter during operation in Fallujah, Iraq, during Operation IRAQI FREEDOM.

Photo by SFC Johan Charles Van Boers via Wikimedia Commons.

I’ve often said that, from what I can tell — and bearing in mind my entire military experience consists of a .500 record at Risk! — AINO‘s entire force philosophy amounts to “zero casualties, ever”.

Note that this was true even in the 20th century, when America was still America. “Stupendous casualties” by American standards would hardly rate “a spot of bother” by Soviet. Wiki lists the bloodiest American battle as Eisenborn Ridge (part of the Bulge), with approximately five thousand fatalities.

A Soviet commander who didn’t come home with at least five thousand KIA could probably expect to be court-martialed for cowardice.

That same Wiki article separates “battles” from “campaigns” for some reason. There’s an entire “methodology” section I’m not going to wade into, but even looking at “campaigns”, the bloodiest (by their definitions) is Normandy — 29,204 KIA. That’s an entire campaign, which might rate “a hard week’s fighting” by Soviet, German, or Japanese standards.

Please understand, Americans’ unwillingness to take casualties was greatly to their credit. You want to know about “meat assaults”, ask the Germans, Russians, or Japanese (or the British or French in WWI). George Patton might not have been the best American commander, but he was the most American commander — the whole point of battle is to make the other stupid bastard die for his country. I am 100% in favor of minimal losses, for everyone, everywhere.

But “minimal” does not mean “none”. People die in wars. People die training for wars. People die in the vicinity of the training for war, because it’s inherently risky. It doesn’t make one some kind of monster to call these “acceptable” losses; it makes one a realist. One could just as easily say — and with the same justification — that a certain number of car crash fatalities, or iatrogenic deaths, etc. are acceptable losses, because there’s no way to have “interstate commerce” and “modern medicine”, respectively, without them.

The Fistagon seemingly denies this. Forget human losses for a moment, and consider mere equipment. You read up on, say, Air Force fighter planes, and you’re forced to conclude that their operations assume that all planes will be fully operational at all times. Again, saying nothing of the pilots, just the airframes. The Navy seems to assume that all ships everywhere will not only be serviceable, but actually in service, at all times. Just recently, they shot off all their ammo at Houthi and the Blowfish … and seemingly had no idea what to do, because as Milestone D walked us through it, it’s impossible to rearm while underway.

Think about that for a second. How the fuck is that supposed to work in a real war? Can we just put the war on pause for a few months, so all our ships can head back to port to reload?

In fact, I’d go so far as to speculate that that’s the origin of the phrase “meat assault”. What The Media are calling a “meat assault” is simply what was known to a sane age as “an assault”. No qualifiers. You know, your basic attack — go take that hill, and if you take the hill, and if enough of the attacking force survives to hold it, that’s a win. People who absolutely should know better, though, don’t see it that way.

Since we’re here … I remember having conversations with some folks in College Town re: the Battle of Fallujah, while it was happening (technically the Second Battle of Fallujah). Now, obviously quite a few of my interlocutors were ideologically committed to the position that this was senseless butchery. And in the fullness of time, I too have come around to the position that the entire Operation Endless Occupation was senseless butchery. But leaving all that aside, the point I was trying to make was a simple one: Total US casualties were 95 killed, 560 wounded.

Every one of them a senseless crime, I now believe, but considering Fallujah strictly as a military operation, that’s amazing. House-to-house fighting in a heavily urban area, against a fanatically committed opponent who was willing, indeed eager, to use every dirty trick in the book … and US forces took 655 total casualties. That’s about as well as it can possibly be done. The Red Army probably lost 655 men on the train ride getting to Stalingrad. I wouldn’t be surprised at all to learn that 655 is the daily casualty figure across the entire front in Ukraine … hell, I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that there are lots of individual sectors in Ukraine taking those kinds of daily losses. 655 is pretty damn good …

… but I was called every dirty name they could think of for suggesting it. I was called dirty names by people who called themselves conservatives, who were such ostentatious “patriots” that they’d embarrass Toby Keith.

Fallujah was fought in 2004, a time that seems like the Blessed Land of Sanity compared to now. AINO simply won’t take casualties. The Pentagram won’t — lose a tank, and you lose your job. (In battle, obviously. If you abandon it to the Taliban, no problem. And of course if you lose an entire war, it’s medals and promotions for everyone). And because the high command won’t, the field commanders won’t either. And because they won’t … well, “desertion” is an ugly word, but let’s just say Tim Walz won’t be the only guy who suddenly needs to be elsewhere right before it’s time to ship out. And as for the guys actually shanghaied into whatever foreign fuckup … well, “mutiny” is an even uglier word, but does anyone want to bet against it?

August 7, 2024

QotD: The crew of HMS Sheffield in the Falklands

But it’s 40 years since the Falklands. And from that we get this:

May 4th 1982: As HMS Sheffield is abandoned and the fire spreads towards the Sea Dart ammunition. The remaining crew gather on the foredeck singing “Always look on the bright side of life”.

Now I have heard that story and I’ve always thought it were more than a little bit mythmaking. And yet, and yet. Someone I know (our fathers knew each other, he took a sister out a few times, we worked together for 6 months later on) was actually there. Running the flight control stuff from the next ship over:

Singing led by the FC that we had loaned to them. One of our Sea Kings closed on the fo’c’sle to pick up wounded and saw them all swaying from side to side with their arms outstretched. I learned why when he got back.

I’ll take that as being something that really happened then. Not for publication, not something published for home consumption, but something that actually happened. Young men, on a burning ship, not knowing whether they’d be lifted off before the fire got to the missiles and the kaboom of their little bits all over the South Atlantic. […]

We’re a weird, weird culture here in Britain. We will, and do, take the piss out of absolutely anything, including our own impending death.

Now, whether that’s quite what the economists mean by institutions that aid in economic development is another thing but it is indeed one of those institutions of that British culture.

It’s also wholly glorious but then I’m a Brit so I would say that, wouldn’t I?

Tim Worstall, “The British Are A Very, Very, Weird People”, It’s all obvious or trivial except …, 2024-05-06.

July 14, 2024

Britain’s First Naval Defeat in 100 years – Coronel 1914

Historigraph

Published Sep 26, 2020

July 12, 2024

New Canadian submarines and icebreakers promised at NATO Summit

Under reportedly intense pressure from NATO allies, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau grudgingly promises to begin the (usually decades-long) process of purchasing new submarines for the Royal Canadian Navy:

The Canadian government announced today it is “taking the first steps” towards buying 12 conventionally-powered, under-ice capable submarines — a massive acquisition with numerous shipbuilders from the around world already eyeing the program reported to be worth at least $60 billion Canadian dollars.

“As the country with the longest coastline in the world, Canada needs a new fleet of submarines — and today, we’ve announced that we will move forward with this acquisition,” Bill Blair, minister of national defence, said in a statement published during the NATO Summit being held this week in Washington, DC. “This new fleet will enable Canada to protect its sovereignty in a changing world, and make valuable, high-end contributions to the security of our partners and NATO allies.”

Canada has been eyeing the acquisition of a new class of submarines to replace its four aging Victoria-class boats since at least April 2023, and Blair himself was the target of criticism earlier this year after he included language about the acquisition in a major defense policy document that critics labeled as “wishy washy”.

In an op-ed for Breaking Defense published ahead of the NATO summit, Blair said that Canada was still pursing the submarine plan, and emphasized that the investment would help his nation cross the 2 percent GDP target.

The government’s press release does not include a price estimate for the program, but the Ottawa Citizen has previously reported that the Royal Canadian Navy tagged the acquisition at $60 billion Canadian dollars ($44 billion USD).

Another item from Breaking Defence details a new trilateral agreement with Finland and the United States to develop a joint design for a “fleet” of icebreakers:

Originally ordered in 2008 for delivery in 2017, the CCGS John G. Diefenbaker is now expected to enter service in 2030.

Canadian Coast Guard conceptual rendering, 2012.

The US, Canada and Finland announced today a new trilateral effort, dubbed the Icebreaker Collaboration Effort or “ICE Pact”, to work together on the production of a “fleet” of new polar icebreakers, in what a US official said was a “strategic imperative” in the race of dominance of the high north.

The initiative, to be formalized in a memorandum of understanding by the end of the year, calls for better information sharing on ship production, collaboration on work force development — including better allowing workers and experts to train at each other’s yards — and an “invitation” to other allies and partners to buy icebreakers from ICE Pact members.

“Due to the capital intensity of shipbuilding, long-term, multi-ship orderbooks are essential to the success of a shipyard,” the White House said in its announcement. “The governments of the United States, Canada, and Finland intend to leverage shipyards in the United States, Canada, and Finland to build polar icebreakers for their own use, as well as to work closely with likeminded allies and partners to build and export polar icebreakers for their needs at speed and affordable cost.”

Ahead of the announcement, White House Deputy National Security Advisor for International Economics Daleep Singh framed the partnership as a commercial and industrial boon, but also one with national security implications: It is, in part, a message to Russia and China that the US and its partners “intend … to project power into the polar regions to enforce international norms and treaties that promote peace and prosperity in the arctic and Antarctic.”

June 5, 2024

HMCS Charlottetown: A formidable submarine-hunting force in Nato’s fleet

Forces News

Published Mar 1, 2024Conceived in the middle of the Cold War era, the Canadian Royal Navy frigate HMCS Charlottetown has evolved over three decades of service, becoming one of the most capable and adaptable ships in Canada’s navy.

After setting sail for Nato’s Exercise Steadfast Defender in the North Sea, she made a stop in Edinburgh en route to participating in the alliance’s largest training mission since the Cold War.

(more…)