The History Guy: History Deserves to Be Remembered

Published 14 Jul 2017The History Guy remembers when the hopes to restore the Second French Empire die in South Africa with Prince Imperial, the last Napoleon. It is history that deserves to be remembered.

The History Guy uses images that are in the Public Domain. As photographs of actual events are often not available, I will sometimes use photographs of similar events or objects for illustration.

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TheHistoryGuy

The History Guy: Five Minutes of History is the place to find short snippets of forgotten history from five to fifteen minutes long. If you like history too, this is the channel for you.

The episode is intended for educational purposes. All events are presented in historical context.

#worldhistory #thehistoryguy #militaryhistory

March 7, 2020

The death of Prince Imperial, The Last Napoleon

February 13, 2020

The Animated History of Italy | Part 2

Suibhne

Published 23 Apr 2018The Armchair Historian Collab: https://youtu.be/vGM54x0LsII

Beginning part two, Italy has been recaptured by the Byzantines thanks to the tenacious ambitions of Emperor Justinian. But throughout the Middle Ages, the land became a battleground for more powerful empires. The 19th Century Italian revolution would see the peninsula swept up in the waves of nationalism that was taking the continent by storm.

October 14, 2019

Cavalry Combat & Tactics during the Napoleonic Era

Military History Visualized

Published 20 Jan 2018This video gives insights in cavalry combat and tactics during the era of Napoleon. This includes cavalry types, forms of combat, formations, organization, principles and many more.

Link to History Gaming Verified: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCoeY…

»» SUPPORT MHV ««

» patreon – https://www.patreon.com/mhv

» paypal donation – https://www.paypal.com/cgi-bin/webscr…Military History Visualized provides a series of short narrative and visual presentations like documentaries based on academic literature or sometimes primary sources. Videos are intended as introduction to military history, but also contain a lot of details for history buffs. Since the aim is to keep the episodes short and comprehensive some details are often cut.

» SOURCES «

Rothenberg Gunther E.: The Art of Warfare in the Age of NapoleonNosworthy, Brent: Battle Tactics of Napoleon and his Enemies

Bruce, Robert B.; Dickie, Iain; Kiley, Kevin; Pavkovic, Michael F.; Schneid, Frederick C.: Fighting Techniques of the Napoleonic Age 1792 – 1815: Equipment, Combat Skills, and Tactics

Ortenburg, Georg: Waffen der Revolutionskriege 1792-1848

Planert, Ute: “Die Kriege der Französischen Revoluation und Napoleons. Beginn einer neuen Ära der europäischen Kriegsgeschichte oder Weiterwirken der Vergangenheit?” In: Beyrau, Dietrich; Hochgeschwender, Michael; Langewiesche, Dieter (Hrsg.): Formen des Krieges. Von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart, S. 149-162

Rogers, H.C.B.: Napoleon und seine Armee / Napoleon’s Army

Browing, Peter: The Changing Nature of Warfare. The Development of Land Warfare from 1792 to 1945

Citino, Robert M.: The German Way of War

Chandler, David: The Art of Warfare in the Age of Marlborough

Philip J. Haythornthwaite: Weapons & Equipment Of The Napoleonic Wars

Hughes, B. P.: Firepower – Weapon Effectiveness on the Battlefield, 1630-1850

Lind, William S.: “Maneuver”; in: Margiotta, Franklin (ed): Brassey’s Encyclopedia of Land Forces and Warfare, p. 661-667

AskHistorians: How does a commander screen his army?

https://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistorian…Russell, Jill R.: With rifle and bibliography: General Mattis on professional reading

http://www.strifeblog.org/2013/05/07/…» DISCLAIMER «

Amazon Associates Program: “Bernhard Kast is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to amazon.com.”Bernhard Kast ist Teilnehmer des Partnerprogramms von Amazon Europe S.à.r.l. und Partner des Werbeprogramms, das zur Bereitstellung eines Mediums für Websites konzipiert wurde, mittels dessen durch die Platzierung von Werbeanzeigen und Links zu amazon.de Werbekostenerstattung verdient werden können.

» TOOL CHAIN «

PowerPoint 2016, Word, Excel, Tile Mill, QGIS, Processing 3, Adobe Illustrator, Adobe Premiere, Adobe Audition, Adobe Photoshop, Adobe After Effects, Adobe Animate.

August 31, 2019

History Summarized: French Empire (Ft. Armchair Historian!)

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published on 30 Aug 2019Check out the Armchair Historian channel for more on French Vietnam and the battle of Dien Bien Phu: https://youtu.be/IJ051WyUsW8

Dubious morality, drawn out timescales, intricate royal politics, worldwide stages — Colonialism be like that sometimes. And by “Like That” I mean impenetrably complicated. I did my best, I’ll say that, but oh man is history a mess in the 15-1900s. This stuff is the reason I had so much trouble with history for so long. It’s just so DENSE.

ANYWAY, join Blue and Griffin the Armchair Historian for a look into the history of the multiple successive French Empires. Listen carefully as Blue makes imperceptibly subtle commentary about his extremely non-biased opinions on this chapter in history, and laugh together as we analyze the historical significance of Napoleon Bonaparte’s anime hair.

NOTE on 6:14 — I say Napoleon became Emperor in 1802. That’s a mistake. In 1802, the constitution of France was amended to make the position of Consul permanent, but Napoleon did not become the Emperor until 1804, when he declared the French Empire. That’s my bad.

NOTE on 11:25 — French Guiana, on the northeast coast of South America, remained part of France following the decolonization of Africa. That’s a mapping mix-up.

DISCORD: https://discord.gg/sS5K4R3

PATREON: https://www.Patreon.com/OSP

August 17, 2019

History Summarized: Malta

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published on 16 Aug 2019Go to https://NordVPN.com/overlysarcastic and and use code

OVERLYSARCASTICto get 75% off a 3 year plan and an extra month for free. Protect yourself online today!Malta, the Island of A Dozen Empires, chilling in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, is one of the most social butterflies in History. Having played host to or fought against every major power in the Mediterranean, this island bears a gorgeous architectural and linguistic record of its past, and is still a treasure to behold in the modern day. I’ve covered a lot of nations and empires in my time here, but between the rich cultural blends, the overflowing artistic treasures, and the Still-In-One-Piece-ness of it all, Malta may have one of the strongest claims to being the Winner of History in my book. What’s so special about Malta? Watch and find out!

NOTE on 7:00 – 7:08 — I’m cheating the time-scales a little here. This church, the Rotunda of Mosta, was actually built mid 1800s. Malta’s lavish church construction continued nearly unabated from C. 1565 to the modern day, so I use this example here — but St Paul’s Co-Cathedral in Valletta, shown from 6:27-6:33 is a better example of pure original Baroque construction. Honestly, all of the churches in Malta deserve a look if you’re curious.

PATREON: https://www.Patreon.com/OSP

DISCORD: https://discord.gg/sS5K4R3

April 14, 2019

British diplomatic blunders in history – German unification

An interesting article in Vox, suggesting that the gradual unification of all the German principalities, electorates, duchies, counties, bishoprics, free cities, and miscellaneous other semi-independent bits and bobs of the Holy Roman Empire was not inevitable and that — absent British blundering after the Napoleonic wars — it would have produced a very different 20th century:

The Holy Roman Empire in 1789, before Napoleon “rationalized” hundreds of smaller entities into the Confederation of the Rhine.

Image from Wikimedia Commons.

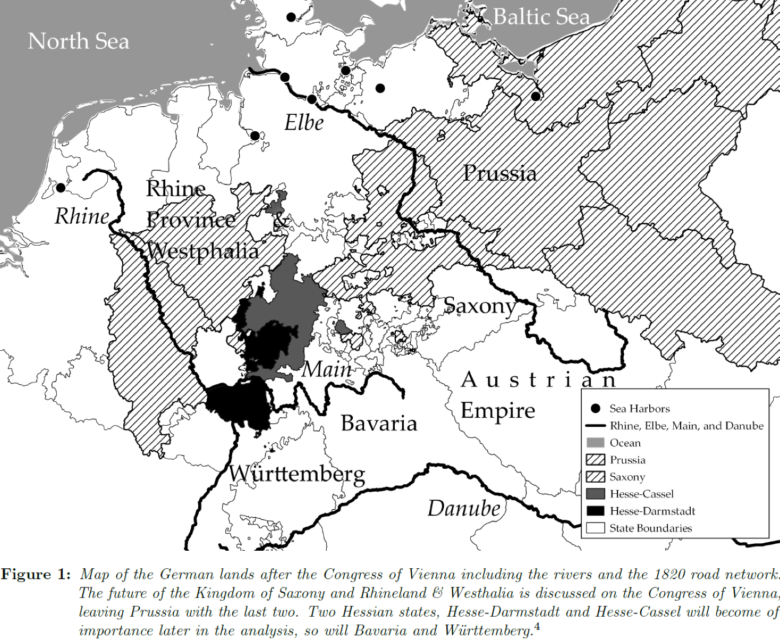

The boundaries of states are the heart of many recent debates, be it the European refugee crisis, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), or Brexit (Snower and Langhammer 2019). After decades of stability, today we are again seeing heated discussions about the shape and extent of political borders. Clearly, borders are neither naturally given nor random. In Europe and elsewhere, the current state borders have been formed and changed over centuries, sometimes peacefully, often in bloody wars. In Huning and Wolf (2019), we look at the formation of the German nation state led by Prussia and trace it back to a change in borders decided at the Congress of Vienna in 1814/15.

In a nutshell, we have two findings:

- First, the geographic position of a state can be a crucial factor for institutional change and development.

- Second, the formation of the German Zollverein in 1834 under Prussian leadership was a truly European story, involving Britain, the Russian Empire, and the Belgian revolution of 1830/31. We show in particular that the Zollverein formed as an unintended consequence of Britain’s intervention in 1814/15 to push back Russian influence over Europe.

In theory, why would the geographic position of a state relative to that of other states matter? Intuitively, it should matter as long as the costs of trade and factor flows depend on their routes. If a large share of my trade has to pass the territory of one or several neighbours, my trade and trade policy will depend on the trade policy of my neighbours. Moreover, if tariffs are levied not only on imports but also on transit trade, as was general practice until the Barcelona Statute of 1921 (Uprety 2006), policymakers face the problem of multiple marginalisation, which is well known from the literature on supply chains. In our work, we provide a simple theoretical framework (in partial equilibrium) to show how the location of a revenue maximising state planner will affect its ability to set tariffs. Some states can increase their tariff revenue at the expense of their hinterland. Next, we show that a customs union can be beneficial for a group of states exactly because it solves the problem of multiple marginalisation.

A major challenge to testing our idea empirically is that a state’s political boundaries (and hence its location) do not change very often, and if they do, the change is unlikely to be unrelated to trade or factor flows. However, the formation of the German Zollverein in 1834 can be considered as a quasi-experiment. Let us briefly revisit this historical episode. At the end of the Napoleonic wars of 1792-1814/15, only Russia and the UK were left as major military powers. Habsburg, Prussia, and the defeated France attempted to consolidate their positions at the expense of the many smaller states that had just about survived the wars, notably the former allies of Napoleon such as Saxony and Poland. Overall, the negotiations at the Congress of Vienna in 1814 were dominated by military-strategic considerations between the two great powers. Russia wanted to expand westwards, Prussia was desperate to annex the populous Kingdom of Saxony, which bordered Prussia in the south and would create a large and coherent territory. To this end, Prussia was willing to give up not only her Polish territories to Russia, but also her positions and claims on the Rhineland (Müller 1986). This met stiff resistance from Britain, joined by Habsburg and France, which feared a new Russian hegemony on the continent – the ‘Polish Saxon question’. After weeks of diplomatic struggle, the outcome was a division of Saxony, another division of Poland and Prussia being established as the “warden of the German gate against France” (Clapham 1921: 98). Figure 1 shows the result of these negotiations.

H/T to Continental Telegraph for the link.

August 27, 2018

Feature History – Peninsular War

Feature History

Published on 20 Aug 2017Hello and welcome to Feature History, featuring the Peninsular War and not much else. It’s not called Peninsular War and other stuff, just Peninsular War so really you can’t complain.

Help me defeat Napoleon (or not)

https://www.paypal.me/FeatureHistory

Patreon

https://www.patreon.com/FeatureHistory

https://twitter.com/Feature_History

Discord

https://discord.gg/Zbk4CvR

———————————————————————————————————–

I do the research, writing, narration, art, and animation. Yes, it is very lonely

April 16, 2017

The tale of unsalted butter in French cuisine

At his new blog, Splendid Isolation, Kim du Toit explains the historical roots of a French culinary oddity:

One of the quirks of French cuisine is that most often the butter is unsalted, and at a French dinner table you will usually find a tiny cruet of salt with a microscopic spoon inside, so that you can salt your butter (or not) according to taste. To someone like myself, accustomed only to salted butter, this seemed like an affectation, but it wasn’t that at all: it was the result of taxation, and this is one of the things changed forever by Napoleon’s administrative reforms.

One of the best parts of our U.S. Constitution is the “interstate commerce” clause, which forbids states from levying taxes on goods and services passing from one state to another, and through another in transit. This was not the case in pre-Napoleonic France. Goods manufactured in, say, Gascony or Provence would pass through a series of customs posts en route to Paris, and at each point the various localities would levy excise taxes on the goods, driving up the final price at its eventual destination.

Which brings us to salt. French salt, you see, was produced mainly on the Atlantic coastline, and was a major “export” of Brittany to the rest of France. Butter, of course, was produced universally — in and outside Paris and ditto for every major city — but the salt for the butter came almost exclusively from Brittany, and having been taxed multiple times by the time it reached points east like Paris or Lyons, it was expensive. So the cuisine and eating habits in those parts developed without the use of salt — or, if salt was requested, at an added cost. It’s why, to this day, many French recipes use unsalted butter as an ingredient. (In contrast, butter for local consumption in western France was [and still is] almost always salted, because salt was dirt cheap there.)

Napoleon’s reforms did away with all that; he saw to it that the douane locale checkpoints and toll booths along the main roads were abolished (causing salt prices in eastern France to plummet and become a mainstay of French cuisine at last). And when the towns and villages protested about the loss of tax revenue, Napoleon made up the shortfall with “federal” funds out of the national treasury.

Of course, the French treasury had in the meantime been emptied out by, amongst other things, the statist welfare policies of the Revolutionary government (stop me if this is starting to sound familiar). Which is why, to raise money, Napoleon invaded wealthy northern Italy and western Germany (as it is now), pillaged their rich cities’ treasuries and garnered revenue from the wealthy aristocracy, who paid bribes to avoid having their palaces sacked and their wealth confiscated.

April 15, 2017

Charles Joseph Minard

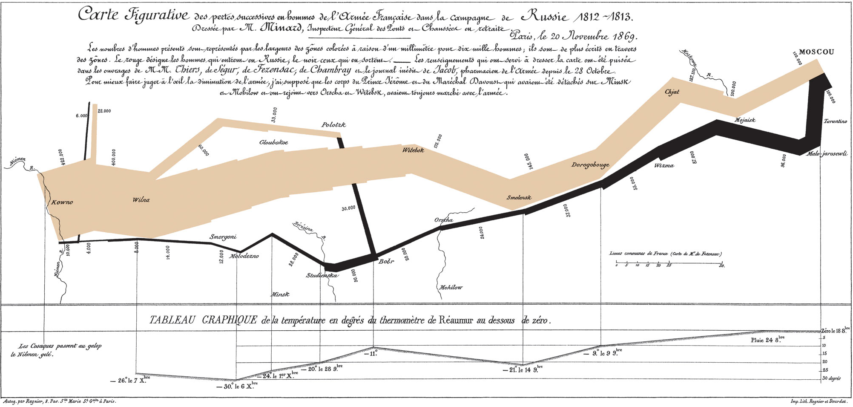

I first encountered Charles Joseph Minard’s best-known work in Edward Tufte’s The Visual Display of Quantitative Information in the late 1980s:

The map’s French caption reads:

Figurative Map of the successive losses in men of the French Army in the Russian campaign 1812-1813.

Drawn up by M. Minard, Inspector General of Bridges and Roads in retirement. Paris, November 20, 1869.

The numbers of men present are represented by the widths of the colored zones at a rate of one millimeter for every ten-thousand men; they are further written across the zones. The red [now brown] designates the men who enter into Russia, the black those who leave it. —— The information which has served to draw up the map has been extracted from the works of M. M. Thiers, of Segur, of Fezensac, of Chambray, and the unpublished diary of Jacob, pharmacist of the army since October 28th. In order to better judge with the eye the diminution of the army, I have assumed that the troops of prince Jerome and of Marshal Davoush who had been detached at Minsk and Moghilev and have rejoined around Orcha and Vitebsk, had always marched with the army.

The scale is shown on the center-right, in “lieues communes de France” (common French league) which is 4,444m (2.75 miles).

The lower portion of the graph is to be read from right to left. It shows the temperature on the army’s return from Russia, in degrees below freezing on the Réaumur scale. (Multiply Réaumur temperatures by 1¼ to get Celsius, e.g. −30°R = −37.5 °C) At Smolensk, the temperature was −21° Réaumur on November 14th.

(Image and translation from Wikimedia)

In National Geographic, Betsy Mason reveals more about the man who created the “best graphic ever produced”:

Charles Joseph Minard’s name is synonymous with an outstanding 1869 graphic depicting the horrific loss of life that Napoleon’s army suffered in 1812 and 1813, during its invasion of Russia and subsequent retreat. The graphic (below), which is often referred to simply as “Napoleon’s March” or “the Minard graphic,” rose to its prominent position in the pantheon of data visualizations largely thanks to praise from one of the field’s modern giants, Edward Tufte. In his 1983 classic text, The Visual Display of Quantitative Information, Tufte declared that Napoleon’s March “may well be the best statistical graphic ever produced.”

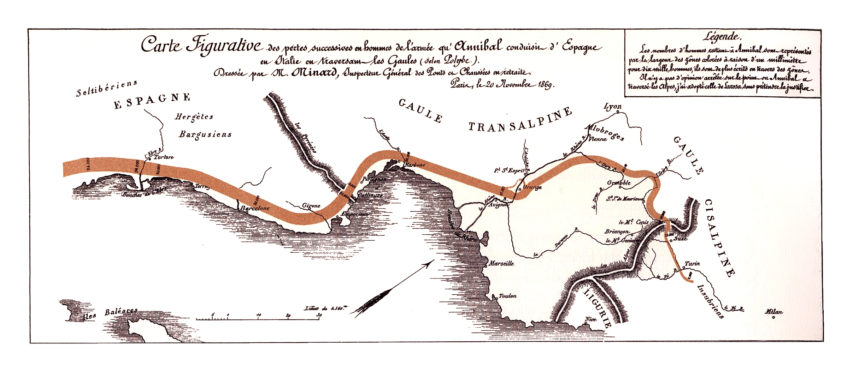

Today Minard is revered in the data-visualization world, commonly mentioned alongside other greats such as John Snow, Florence Nightingale, and William Playfair. But Minard’s legacy has been almost completely dominated by his best-known work. In fact, it may be more accurate to say that Napoleon’s March is his only widely known work. Many fans of the March have likely never even seen the graphic that Minard originally paired it with: a visualization of Hannibal’s famous military campaign in 218 BC, as seen in the image below.

Graphic information of the men losses in the raid of the troops of Hannibal from Spain to Italy (Wikimedia)

On its face, it may not seem remarkable that Minard is remembered for this one piece of work; after all, many people owe their fame to a single great achievement, and the Napoleon graphic is certainly worthy of its reputation. But Minard was most definitely not a one-hit wonder.

February 6, 2017

QotD: General officer ranks in the Waterloo campaign

There were a lot of generals involved in the campaign in northern France and Flanders that began on June 14, 1815, and culminated in the memorable Battle of Waterloo on June 18th. Altogether there were 240 of them, to command nearly 360,000 troops. And since the troops came from a lot of different armies — British, French, Prussian, Netherlands, Hanover, Brunswick, and a few others, telling the generals apart can be a bit confusing.

[…]

Note that the rank structure is not really comparable to that prevailing today in the U.S. Army. The functional equivalent of a British major general or a French general de brigade or marechal de camp would actually be brigadier general based on their commands. The French rank system was actually much more complicated than may appear from the table. To begin with, the highest actual rank in the army was general de division. Marechal de l’Empire was technically a distinction, not a rank. Now it gets really complicated. A corps commander who was officially a general de division might by courtesy be designated a general de corps d’armee. However, a general de division might also sometimes be referred to as a lieutenant-general, particularly if he was functioning in a staff position. Meanwhile, the chief-of-staff of the army was designated major general. In addition, an officer commanding a brigade was more likely to be designated a marechal de camp (i.e., “field marshal”) rather than general de brigade, which was reserved for officers with special duties, such as the commanders of the regiments of the Garde Imperial. This complexity had developed as a result of the Revolution, which favored functional titles for military officers, chef de battailon for example, rather than major. Unfortunately, staff personnel often required rank, so the old Royal hierarchical titles of rank survived for a long time alongside the functional Revolutionary ones.

Further complicating matters was the fact that in all the armies an officer’s social rank was often used rather than his military rank. Thus, although Wellington was a Field Marshal he was usually referred to as “His Grace, the Duke” without his military rank. In Wellington’s case this could become quite complicated, as he was a duke thrice over, the Portuguese and Spanish having created him such even before the British, and he was also a Prince of the Netherlands. As each of these gave him a different title, references to him in Portuguese, Spanish, or Dutch works can easily become obscure. For example, to the Portuguese he was the Duque de Douro, and one Portuguese language history of the Peninsular War nowhere uses any other name for him. Then there is the problem of multiple ranks. Wellington, for example, was a field marshal in the British, Prussian, Netherlands, and Portuguese armies, as well as being a Capitan General in the Spanish Army. Although none of the other officers in the campaign had so many different ranks, several held more than one. For example, the Prince of Orange was a Dutch field marshal and a general in the British Army, while the Duke of Brunswick, who commanded his division in his capacity as duke, was also a lieutenant-general in the British Army.

Al Nofi, “Al Nofi’s CIC”, Strategy Page, 2000-02-01.

January 19, 2017

Simón Bolívar – II: Francisco de Miranda – Extra History

Published on Nov 26, 2016

When Napoleon conquered Spain, the Spanish colonies no longer had a clear leader to follow. Bolívar seized on this opportunity to promote his dreams of Venezuelan independence, but he stumbled from lack of experience. A man named Francisco de Miranda took control instead.

November 30, 2016

QotD: Napoleon’s misogynistic views

… “What do most ladies have to complain of? Don’t we acknowledge they have souls … They demand equality! Pure madness! Woman is our property … just as the fruit tree belongs to the gardener.” Only inadequate education could make a wife think she was on the same level as her husband. Convinced of “the weakness of the female intellect”, he considered his brother Joseph extraordinary in enjoying the other sex’s company as well as their bodies — “He’s forever shut away with some woman reading Torquato Tasso and Aretino.”

However gracefully phrased, his opinion of adultery revealed utter cynicism. In the end it is “a joke behind a mask … not by any means a rare phenomenon but a very ordinary occurrence on the sofa”. He had surprisingly modern views on women as soldiers. “They are brave, incredibly enthusiastic and capable of the most frightful atrocities … In a real war between men and women the only thing which would handicap women would be pregnancy, since the women of the people are just as strong as most men.” (In this he was far more progressive than the Führer.)

Desmond Seward, Napoleon and Hitler: A comparative biography, 1988.

June 2, 2016

History Buffs: Waterloo

Published on 16 Feb 2016

For those of you want realism in their historical movies. To watch a film that cares as much about about authenticity as you do. Look no further. Over the course of this video you will hopefully understand why this film means so much to me. This is Waterloo

April 2, 2016

QotD: The Anglo-Saxon encirclement strategy

In retrospect the fight against Napoleon seems to have engendered a new strategic method, later employed against Germany in two world wars and against the Soviet Union thereafter. The French might call it the Anglo-Saxon encirclement strategy. Its essential aim was to avoid direct combat with a formidable enemy, or at least to limit engagement to a minimum. Instead of confronting one vast army with another – at Waterloo there were only 25,000 British troops – the Anglo-Saxon approach was to take on the big beast by assembling as many neighbourhood dogs and cats as possible, with a few squirrels and mice thrown in. With the obvious exception of the Western Front in the First World War, that is how the two world wars were fought, with an ever longer list of allies large, small and trivial (e.g. Guatemala, whose rulers could thereby expropriate the coffee plantations of German settlers), and that is how the Soviet Union was resisted after 1945, with what eventually became the North Atlantic Alliance. Like the anti-Napoleon coalition, Nato was – and remains – a ragbag of member states large and small, of vastly different capacity for war or deterrence, not all of them loyal all the time, though loyal and strong enough. Like the challenge to British diplomacy in the struggle against Napoleon, the great challenge to which American diplomacy successfully rose was to keep the alliance going by tending to the various political needs of its member governments, even those of countries as small as Luxembourg, whose rulers sat on all committees as equals, even though they could never field more than a single battalion of troops.

Now it is the turn of the Chinese, whose strength is still modest yet growing too rapidly for comfort, and who are inevitably provoking the emergence of a coalition against them; the members range in magnitude from India and Japan down to the Sultanate of Brunei, in addition of course to the US. Should they become powerful enough, the Chinese will force even the Russian Federation into the coalition regardless of the innate preferences of its rulers, for strategy is always stronger than politics, as it was for the anti-communist Nixon and the anti-American Mao in 1972. China cannot therefore overcome its inferiority to the American-led coalition by converting its economic strength into aircraft carriers and such, any more than Napoleon could have overcome strategic encirclement by winning one more battle. The exact repetition of Napoleon’s fatal error by imperial and Nazi Germany is easily explained: history teaches no lesson except that there is a persistent failure to learn its lessons. It remains to be seen whether the Chinese will do any better.

Edward Luttwak, “A Damned Nice Thing”, London Review of Books, 2014-12-18.

March 29, 2016

QotD: Strategy’s underpinnings

That is how the logic of strategy works. Its different levels might be thought of as the floors of a building. Nothing can be achieved at the operational level of strategy without adequate tactical capacity below it — there’s no point in moving units around in clever manoeuvres if they cannot fight at all — just as there is no capacity at the tactical level if there are no supplies and no weapons. The technical level of strategy is just as essential, for all its simplicity as compared to the mysteries of unit cohesion, morale and leadership which largely determine tactical strength. But this edifice of several stories has a most peculiar feature: there are no stairs or elevators from the operational level, where battles are fought, up to the level of grand strategy, where entire wars are fought with every political and material strength or weakness in play, including alliances and enmities. Absent overwhelming superiority to begin with, no war fought with the wrong allies against the wrong enemies can yield victory, even if a hundred battles are won. By 1814, that was Napoleon’s predicament, as it would be for Germany in both world wars: German forces fought skilfully and often ferociously to win again and again in battles large and small, but nothing could overcome the consequences of siding with the decrepit Ottoman and Habsburg Empires against the British, French, Japanese and Russian empires the first time around, or with Bulgaria and Italy against all the Great Powers but Japan the second time.

Edward Luttwak, “A Damned Nice Thing”, London Review of Books, 2014-12-18.