In 2005, [Gertrude Himmelfarb] published The Roads to Modernity: The British, French, and American Enlightenments. It is a provocative revision of the typical story of the intellectual era of the late eighteenth century that made the modern world. In particular, it explains the source of the fundamental division that still doggedly grips Western political life: that between Left and Right, or progressives and conservatives. From the outset, each side had its own philosophical assumptions and its own view of the human condition. Roads to Modernity shows why one of these sides has generated a steady progeny of historical successes while its rival has consistently lurched from one disaster to the next.

By the time she wrote, a number of historians had accepted that the Enlightenment, once characterized as the “Age of Reason”, came in two versions, the radical and the skeptical. The former was identified with France, the latter with Scotland. Historians of the period also acknowledged that the anti-clericalism that obsessed the French philosophes was not reciprocated in Britain or America. Indeed, in both the latter countries many Enlightenment concepts — human rights, liberty, equality, tolerance, science, progress — complemented rather than opposed church thinking.

Himmelfarb joined this revisionist process and accelerated its pace dramatically. She argued that, central though many Scots were to the movement, there were also so many original English contributors that a more accurate name than the “Scottish Enlightenment” would be the “British Enlightenment”.

Moreover, unlike the French who elevated reason to a primary role in human affairs, British thinkers gave reason a secondary, instrumental role. In Britain it was virtue that trumped all other qualities. This was not personal virtue but the “social virtues” — compassion, benevolence, sympathy — which British philosophers believed naturally, instinctively, and habitually bound people to one another. This amounted to a moral reformation.

In making her case, Himmelfarb included people in the British Enlightenment who until then had been assumed to be part of the Counter-Enlightenment, especially John Wesley and Edmund Burke. She assigned prominent roles to the social movements of Methodism and Evangelical philanthropy. Despite the fact that the American colonists rebelled from Britain to found a republic, Himmelfarb demonstrated how very close they were to the British Enlightenment and how distant from French republicans.

In France, the ideology of reason challenged not only religion and the church, but also all the institutions dependent upon them. Reason was inherently subversive. But British moral philosophy was reformist rather than radical, respectful of both the past and present, even while looking forward to a more enlightened future. It was optimistic and had no quarrel with religion, which was why in both Britain and the United States, the church itself could become a principal source for the spread of enlightened ideas.

In Britain, the elevation of the social virtues derived from both academic philosophy and religious practice. In the eighteenth century, Adam Smith, the professor of moral philosophy at Glasgow University, was more celebrated for his Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759) than for his later thesis about the wealth of nations. He argued that sympathy and benevolence were moral virtues that sprang directly from the human condition. In being virtuous, especially towards those who could not help themselves, man rewarded himself by fulfilling his human nature.

Edmund Burke began public life as a disciple of Smith. He wrote an early pamphlet on scarcity which endorsed Smith’s laissez-faire approach as the best way to serve not only economic activity in general but the lower orders in particular. His Counter-Enlightenment status is usually assigned for his critique of the French Revolution, but Burke was at the same time a supporter of American independence. While his own government was pursuing its military campaign in America, Burke was urging it to respect the liberty of both Americans and Englishmen.

Some historians have been led by this apparent paradox to claim that at different stages of his life there were two different Edmund Burkes, one liberal and the other conservative. Himmelfarb disagreed. She argued that his views were always consistent with the ideas about moral virtue that permeated the whole of the British Enlightenment. Indeed, Burke took this philosophy a step further by making the “sentiments, manners, and moral opinion” of the people the basis not only of social relations but also of politics.

Keith Windschuttle, “Gertrude Himmelfarb and the Enlightenment”, New Criterion, 2020-02.

March 5, 2025

QotD: British and French Enlightenments

January 22, 2025

“Do not give institutional power to activists” or “moral projects to bureaucrats”, but “Progressivism systematically does both”

Lorenzo Warby on the dangers of enabling totalitarians and suffering the useful idiots in any political system:

The overthrow of Robespierre in the National Convention on 27 July 1794, Max Adamo (1870),

Wikimedia Commons.

Do not give institutional power to activists, as activism — being power without responsibility that readily lauds bad behaviour — attracts manipulative “Cluster B” personalities. Moreover, activism degrades realms of human action by imposing pre-conceived outcomes and constraints on them. We can see this is in all the entertainment franchises whose internal logics of story and canon have been debauched in the service of political messaging.1

Do not give moral projects to bureaucrats, as such projects elevate the authority of the bureaucrats who become moral masters, devaluing the authority of the citizens turned into moral subjects, and so undermines any ethic of service to said citizenry. Such projects also frustrate accountability, as the grand intentions can, and will, be used to shield the bureaucrats from scrutiny. Indeed, moral projects rapidly become moralised projects, whose grand intentions protects, even aggrandise, the self-interest of the bureaucrats.2

Progressivism systematically does both — give institutional power to activists and moral projects to bureaucrats. Hence progressivism has so often proved disastrous for human flourishing. Indeed, it has a powerful tendency to use the grandeur of its moral intentions to free itself from moral constraints: to be moralised, rather than moral.

As various folk “walk away” from what left-progressivism has become, a common sentiment is some version of “this is not the Left I remember” or “this is not what the Left used to stand for”. Yet, one of the striking things about Post-Enlightenment Progressivism (aka “wokery”) within contemporary societies is how thoroughly it is replicating mechanisms of social control familiar to any student of Communism, of Marxist Party-states.

This “not the Left I joined” is typically a notion of “the Left” that does not include Lenin, Stalin, Mao, Pol Pot, Mengistu, Ceausescu … So it is an historically illiterate, “wouldn’t-it-be-nice”, Leftism. Yet it is precisely the Left that does include Lenin, Stalin, Mao, Pol Pot, Mengistu, Ceausescu and so on whose echoes are being played out in our societies.

When we look around our contemporary societies, we have commissars/political officers (aka DEI officers, intimacy consultants, sensitivity readers, bias response teams, etc); Zhdanovism, in the remarkable ideological conformism in the arts, entertainment and gaming (usefully discussed here); Lysenkoism in science journals, especially the genderwoo sex-is-non-binary nonsense, though genetics research and male-female differences also have aspects of it; and censorship that was originally paraded as stopping “hate speech”, now being purveyed as anti-dis/mis/mal-information. Critical Pedagogy — which has become influential in Education Faculties and teacher training — is explicitly about replicating Mao’s Cultural Revolution model of permanent revolution. We have the same, disastrous, patterns of institutional power to activists and moral projects to bureaucrats.

1. There is a large difference from the “we want to be included, we want a say” activism that abolished first the slave trade and then slavery, that abolished laws against Jews and Catholics, that gave us universal male and then female suffrage — what I have called the Emancipation Sequence. Such political movements included previously excluded folk in freedoms and political processes that already existed. They did not give institutional power to activists nor moral projects to bureaucrats.

2. The institutional shrinkage of the Church has not abolished the meaning-and-morality role it used to play, it has just shifted it into academe and the welfare state apparat, making both simultaneously more arrogant and less functional.

December 16, 2024

The academic battle over the legacy of the British Empire

In the Washington Examiner, Yuan Yi Zhu reviews The Truth About Empire: Real histories of British Colonialism edited by Alan Lester:

… the story fitted awkwardly with the new dominant historical narrative in Britain, according to which the British Empire was an unequivocally evil institution whose lingering miasma still corrupts not only its former territories but also modern-day Britain.

When Kipling lamented, “What do they know of England, who only England know?” he was not being elegiac as much as describing a statistical fact. Contrary to modern caricatures, apart from episodic busts of enthusiasm, Britons were never very interested in their empire. At its Victorian peak, the great public controversies were more likely to be liturgical than imperial. In 1948, 51% of the British public could not name a single British colony; three years later, the figure had risen to 59%. Admittedly, this was after Indian independence, but it should not have been that hard. Proponents of the “imperial miasma” theory are right in saying that British people are woefully ignorant about their imperial past; but that was the case even when much of the world was colored red.

The Truth About Empire: Real Histories of British Colonialism is a collection of essays edited by Alan Lester, an academic at the University of Sussex who has been at the forefront of the cultural conflict over British imperialism on the “miasma” side — though, like all combatants, he denies being a participant. Indeed, one of the book’s declared aims is to show that its contributors are not engaged in cultural warring.

Their nemesis, whose name appears 376 times in this book (more often than the word “Britain”) is Nigel Biggar, a retired theologian and priest at the University of Oxford. In 2017, Biggar began a project to study the ethics of empire alongside John Darwin, a distinguished imperial historian. The now-familiar academic denunciations then came along, and Darwin, on the cusp of a quiet retirement, withdrew from the project.

Lester was not part of the initial assault on Biggar but has since then emerged as his most voluble critic. He disclaims any political aims, protesting that he and his colleagues are engaged in a purely scholarly enterprise, based on facts and the study of the evidence.

Yet some of Lester’s public interventions — he recently described a poll showing that British people are less proud of their history than before as an “encouraging sign” — are hard to square with this denial. Biggar, by contrast, is refreshingly honest that his aims are both intellectual and political. I must add that both men are serious scholars, which is perhaps why neither has been able to decisively bloody the other in their jousts.

[…]

“What about slavery?” asks Dubow’s Cambridge colleague Bronwen Everill. Unfortunately, her four pages, which read like a last-minute student essay, do not enlighten us. The most she can manage is to point to an 18th-century African monarch abolishing the slave trade as evidence that the British do not deserve any plaudits for their abolitionist efforts across the world, whose cost has been estimated at 1.8% of its gross domestic product over a period of 60 years.

Meanwhile, Abd al Qadir Kane, Everill’s abolitionist monarch, only objected to the enslavement of Muslims but not to slavery generally, his progressive reputation resting mainly on the misunderstandings of Thomas Clarkson, an overenthusiastic English abolitionist. (Either cleverly or lazily, Everill quotes Clarkson’s misleading account, thus avoiding the need to engage with the historiography on Islamic slavery in Africa.)

Everill’s central argument is that abolitionism allowed Britain to rove the world as a moral policeman and to overthrow rulers who refused to abolish slavery. It is never clear, however, why this was morally bad. If anything, Britain did not go far enough: Well into the 1960s, British representatives still manumitted slaves on an ad hoc basis in its Gulf protectorates, when the moral thing would have been to force their rulers to abolish slavery, at gunpoint if necessary.

December 12, 2024

The dispiriting rise of the “kidult”

Freya India explains the need for modern parents to re-embrace some of the more traditional duties of parents in raising children:

It’s pretty much accepted as fact that parents today are overprotective. We worry about helicopter parenting, and the coddling of Gen Z. But I don’t think that’s the full story. Parents aren’t protective enough.

Or at least, what parents are protective about has changed. They are overprotective about physical safety, terrified of accidents and injuries. But are they protective by giving guidance? Involved in their children’s character development? Protective by raising boys to be respectful, by guiding girls away from bad influences? Protective by showing children how to behave, by being an example?

As far as I can see many parents today are overprotective but also strangely permissive. They hesitate to give advice or get involved, afraid of seeming controlling or outdated. They obsess over protecting their children physically, but have little interest in guiding them morally. They care more about their children’s safety than their character. Protective parenting once meant caring about who your daughter dated, the decisions she made, and guiding her in a good direction. Now it just means preventing injury. And so children today are deprived of the most fundamental protection: the passing down of morals, principles, and a framework for life.

One obvious example of this is that adults act like children now. They talk like teenagers. They use the same social media platforms, play the same video games, listen to the same music. Our world moves too rapidly to retain any wisdom, denying parents the chance to pass anything down or be taken seriously, so they try to keep up with kids, who know more about the world than they do. Fathers are “girl dads” who get told what to think. Mothers are best friends to gossip with. The difference between childhood and adulthood is disappearing, and with it, parental protection.

Beyond that, too, there’s this broader cultural message that adults should focus on their own autonomy and self-actualisation. This very modern belief that a good life means maximum freedom, with as little discomfort and constraint as possible, the way children think. Now nothing should hold adults back. They have a right to feel good, at all times. They stopped being role models of responsibility and became vessels of the only culture left, a therapeutic culture, where it’s only acceptable to be protective of one thing, your own mental health and happiness. Listen to the way adults judge decisions now, how they justify themselves. Parents are celebrated for leaving their families because they were vaguely unhappy or felt they needed to find themselves, even at the expense of their children’s security. Adults talk about finding themselves as much as teenagers do. Parents complain online about the “emotional labour” of caring for family, or express regret for even having children because they got in the way of their goals. Once growing up meant sacrificing for family, giving up some of yourself, that was an honour, that was a privilege, and in that sacrifice you found actual fulfilment, broke free from yourself, moved on from adolescent anxieties, and there, then, you became an adult.

But slowly, without thinking, we became suspicious of adulthood. We debunked every marker and milestone, from marriage to children all the way to adulthood itself. Now we aren’t just refusing to grow up but rejecting the very concept of it. Adulthood does not exist, apparently. It’s a scam, a lie, a myth. Adulthood is a marketing ploy, we say, while wearing Harry Potter merch and going to Disneyland. Adulthood is a performance, apparently, that’s going out of style. “There is nothing, there is nobody which/who would really justify the claim ‘you have to grow up’,” seems to be the sentiment. “For whom? for what?”

December 5, 2024

QotD: Oscar Wilde

That story, I need scarcely say, is anything but edifying. One rises from it, indeed with the impression that the misdemeanor which caused Wilde’s actual downfall was quite the least of his onslaughts upon the decencies — that he was of vastly more ardor and fluency as a cad and poltroon than ever he became as an immoralist. No offense against what the average civilized man regards as proper and seemly conduct is missing from the chronicle. Wilde was a fop and a snob, a toady and a social pusher, a coward and an ingrate, a glutton and a grafter, a plagiarist and a mountebank; he was jealous alike of his superiors and of his inferiors; he was so spineless that he fell an instant victim to every new flatterer; he had no sense whatever of monetary obligation or even of the commonest duties of friendship; he lied incessantly to those who showed him most kindness, and tried to rob some of them; he seems never to have forgotten a slight or remembered a favour; he was as devoid of any notion of honour as a candidate for office; the moving spring of his whole life was a silly and obnoxious vanity. It is almost impossible to imagine a fellow of less ingratiating character, and to these endless defects he added a physical body that was gross and repugnant, but through it all ran an incomparable charm of personality, and supporting and increasing that charm was his undoubted genius. Harris pauses more than once to hymn his capacity for engaging the fancy. He was a veritable specialist in the amenities, a dinner companion sans pair, the greatest of English wits since Congreve, the most delightful of talkers, an artist to his finger-tips, the prophet of a new and lordlier aesthetic, the complete antithesis of English stodginess and stupidity.

H.L. Mencken, “Portrait of a Tragic Comedian”, The Smart Set, 1916-09.

November 23, 2024

QotD: Nietzsche’s message

[Nietzsche’s] objection to Christianity is simply that it is mushy preposterous, unhealthy, insincere, enervating. It lays its chief stress, not upon the qualities of vigorous and efficient men, but upon the qualities of the weak and parasitical. True enough, the vast majority of men belong to the latter class: they have very little enterprise and very little courage. For these Christianity is good enough. It soothes them and heartens them; it apologizes for their vegetable existence; it fills them with an agreeable sense of virtue. But it holds out nothing to the men of the ruling minority; it is always in direct conflict with their vigor and enterprise; it seeks incessantly to weaken and destroy them. In consequence, Nietzsche urged them to abandon it. For such men he proposed a new morality — in his own phrase, a “transvaluation of values” — with strength as its highest good and renunciation as its chiefest evil. They waste themselves to-day by pulling against the ethical stream. How much faster they would go if the current were with them! But as I have said — and it cannot be repeated too often — Nietzsche by no means proposed a general repeal of the Christian ordinances. He saw that they met the needs of the majority of men, that only a small minority could hope to survive without them. In the theories and faiths of this majority he has little interest. He was content to have them believe whatever was most agreeable to them. His attention was fixed upon the minority. He was a prophet of aristocracy. He planned to strike the shackles from the masters of the world …

H.L. Mencken, “Transvaluation of Morals”, The Smart Set, 1915-03.

October 30, 2024

Halloween Special: Frankenstein

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published Oct 31, 2017It is a tale. A tale of a man … and a MONSTER!

It’s finally time to talk Frankenstein! Part sci fi, part horror, part opinion piece on the dangers of hubris, this classic story reminds us all to appreciate what’s really important to us: friends, family, loved ones, and most importantly, NOT creating twisted mockeries of God’s creations in an attempt to reach beyond the veil of life itself.

Nnnnnnnow here is a riddle to guess if you can,

sings the tale of Frankenstein!

Who is the monster and who is the man?~

September 23, 2024

QotD: On Roman Values

I wanted to use this week’s fireside to muse a bit on a topic I think I may give a fuller treatment to later this year, which is the disconnect between what it seems many “radical traditionalists” imagine traditional Roman values to be and actual Roman cultural values.

Now, of course it isn’t surprising to see Roman exemplars mobilized in support of this or that value system, as people have been doing that since the Romans. But I think the disconnect between how the Romans actually thought and the way they are imagined to have thought by some of their boosters is revealing, both of the roman worldview and often the intellectual and moral poverty of their would-be-imitators.

In particular, the Romans are sometimes adduced by the “RETVRN” traditionalist crowd as fundamentally masculine, “manly men” – “high testosterone” fellows for whom “manliness” was the chief virtue. Romans (and Greeks) are supposed to be super-buff, great big fellows who most of all value strength. One fellow on Twitter even insisted that the chief Roman value was VIRILITAS, which was quite funny, because virilitas (“manhood, manliness”) is an uncommon word in Latin, but when it appears it is mostly as a polite euphemism for “penis”. Simply put, this vision bears little relation to actual Roman values. Roman encomia or laudationes (speeches in praise of something or someone) don’t usually highlight physical strength, “high testosterone” (a concept the Romans, of course, did not have) or even general “manliness”. Roman statues of emperors and politicians may show them as reasonably fit, but they are not ultra-ripped body-builders or Hollywood heart-throbs.

Bret Devereaux, “Fireside Friday, March 29, 2024 (On Roman Values)”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2024-03-29.

September 13, 2024

Fiction should have heroes, not merely the morally ambivalent “heroes” modern writers prefer

Tom Knighton is nostalgic for some of the books and movies of his youth, which often had an actual hero you could root for:

Somewhere along the way, fiction started changing.

In my childhood, the nihilism that seems to be so common today wasn’t really a thing. We had grand adventures with heroes who might not have been perfect but were still heroes.

Today, we have a lot of fiction where no one is really the good guy. Rings of Power has been trying to humanize the orcs, making all the good races of Middle Earth darker than they were. Game of Thrones saw just about every truly heroic character killed while so many of the despicable characters lasted until the end.

And that’s a problem. Why?

Well, let’s start with this bit from C.S. Lewis:

Now, I grew up in the era of Rambo and John McClain. I had tough-guy heroes and I also had those that were just regular folks thrust into bad situations.

But there were always good guys and there were always dark forces at work.

The world is more muddied than that, sure, but entertainment doesn’t have to reflect reality perfectly. I mean if that were true, how did Lord of the Rings do so well? Elves and orcs and uruk-hai aren’t exactly real, now are they? Neither are hobbits, Jedi, terminators, or any of a million other fictional creations.

Yet what existed in all of those stories were good guys fighting to put down the evil that arose.

As Lewis argues, it taught my generation and those before and right after mine that cruel enemies can be defeated.

Today, though, we see all too many stories where the enemies prevail, where good fails to triumph over evil, and evil is allowed to remain.

For a while, there was a certain amount of shock value to that. This was when this was the exception rather than a normal thing you would see. It was that moment at the end when you realize the good guy lost despite their best efforts, that revealed at the end that the hero who sacrificed himself to kill the bad guy failed to actually kill him.

July 2, 2024

QotD: The ’60s

I am ashamed of how my generation acted in the 1960s, and the only reason that I am not more angry at myself and my friends is because we were so very young. I’m still puzzling over why we lost our moorings. I’d say it was money. We acted that way because we could afford to. It was the first time in the history of the world that anything like this size of a generation had been anything like that rich, and it was a shock to everybody’s system. There’s nothing we did that Lord Byron wouldn’t have done if he’d had a good stereo.

You have this convergence: an extremely unpopular and possibly unwise war, and birth control. The sudden idea that nothing had any consequences. There’s that Philip Larkin poem — sexual intercourse was invented in 1963. And the drugs went everywhere in a year.

P.J. O’Rourke, interviewed by Scott Walter, “The 60’s Return”, American Enterprise, May/June 1997.

May 23, 2024

“[O]fficial justifications for mass migration often have a creepy, post-hoc flavour about them”

While it sometimes seems that there can’t possibly be mass migration issues other than here in Canada and along the US southern border, eugyppius reminds us that all of the Kakistocrats in western countries are fully in favour of more, and more, and even more inflow without restriction:

An asylum seeker, crossing the US-Canadian border illegally from the end of Roxham Road in Champlain, NY, is directed to the nearby processing centre by a Mountie on 14 August, 2017.

Photo by Daniel Case via Wikimedia Commons.

You might have noticed that mass migration to the West is a huge problem.

It is very bad for native Westerners, because it promises to transform our societies utterly, in permanent ways and not for the better. Curiously, it is also far from great for the centre-left political establishment responsible for promoting mass migration, because it has inspired a vast wave of popular opposition and filled the sails of right-leaning, migration restrictionist parties with new wind. Mass migration is also bad for taxpayers, for domestic security, for the welfare state, for many other aspects of the postwar liberal agenda and for our own future prospects. In short, mass migration is bad for almost everybody and everything.

There is a reason that nations have borders, and this is much the same reason that we have skin and that cells have membranes. You won’t survive for very long if you can’t control what enters you.

Despite the obvious fact that mass migration is bad, our rulers cling to migrationism like grim death. Given a choice between disincentivising asylees and intimidating, browbeating and harassing the millions of anti-migrationists among their own citizens, our governments generally choose the latter path, even though it is obviously the worse of the two.

Additionally unsettling, is the fact that official justifications for mass migration often have a creepy, post-hoc flavour about them. They sound much more like excuses dreamed up after the borders had already been opened, rather than any kind of reason mass migration must occur. When the migrationists really started to go crazy in 2015, for example, we were told that border security was simply impossible in the modern world and that infinity migrants were a force of nature we would have to deal with. That didn’t sound right even at the time, and since the pandemic border closures we no longer hear the inevitability narrative very much, although – and this is very bizarre to type – there is some evidence that high political figures like Angela Merkel believed it at the time. It is well worth thinking about why that might have been the case.

Another excuse that doesn’t make very much sense, is what I’ll call the refugee thesis. We’re told that millions of poor people are forced to endure terrible conditions in the developing world and that it is our moral burden to improve their lot by granting them residence in our countries. That might convince a few teenage girls, but it cannot withstand scrutiny among the rest of us. To begin with, the population of global unfortunates is enormous; the millions of refugees we have already accepted, and the millions that our politicians hope to welcome in the coming years, represent but a vanishing minority – a rounding error – compared to the vast sea of human suffering. It is like trying to solve homelessness by demanding that those in the wealthiest neighbourhoods make their spare bedrooms available to the indigent. Even more telling, however, is that the push to welcome migrants comes precisely as conditions in the developing world have dramatically improved. When things were much worse, we sealed our borders against the global south; now that they are much better, we hear all about how unacceptably inhumane it is to leave the migrants in their native lands.

Other post-hoc arguments, especially those falling in the yay-multiculturalism category, are even less serious. That we need more diversity to “spark innovation” (whatever that means) or that our local cuisines stand to benefit from the spices of the disadvantaged, are excuses of such towering stupidity, that you will lose brain cells thinking about them. As with the refugee narrative, nobody said crazy stuff like this until the migrants had already begun arriving on our shores. And there is another thing to notice about the multiculticult too. This is its blatant flippancy. The premise seems to be that migration is no big deal bro, but also too there are these cool exciting and totally random upsides, like improved local Ethiopian food offerings. It is the very definition of damning with faint praise.

The rest, sadly, is behind the paywall.

April 6, 2024

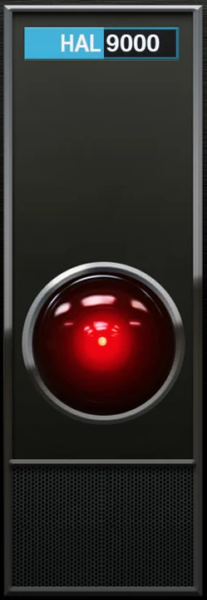

Three AI catastrophe scenarios

David Friedman considers the threat of an artificial intelligence catastrophe and the possible solutions for humanity:

Earlier I quoted Kurzweil’s estimate of about thirty years to human level A.I. Suppose he is correct. Further suppose that Moore’s law continues to hold, that computers continue to get twice as powerful every year or two. In forty years, that makes them something like a hundred times as smart as we are. We are now chimpanzees, perhaps gerbils, and had better hope that our new masters like pets. (Future Imperfect Chapter XIX: Dangerous Company)

As that quote from a book published in 2008 demonstrates, I have been concerned with the possible downside of artificial intelligence for quite a while. The creation of large language models producing writing and art that appears to be the work of a human level intelligence got many other people interested. The issue of possible AI catastrophes has now progressed from something that science fiction writers, futurologists, and a few other oddballs worried about to a putative existential threat.

Large Language models work by mining a large database of what humans have written, deducing what they should say by what people have said. The result looks as if a human wrote it but fits the takeoff model, in which an AI a little smarter than a human uses its intelligence to make one a little smarter still, repeated to superhuman, poorly. However powerful the hardware that an LLM is running on it has no superhuman conversation to mine, so better hardware should make it faster but not smarter. And although it can mine a massive body of data on what humans say it in order to figure out what it should say, it has no comparable body of data for what humans do when they want to take over the world.

If that is right, the danger of superintelligent AIs is a plausible conjecture for the indefinite future but not, as some now believe, a near certainty in the lifetime of most now alive.

[…]

If AI is a serious, indeed existential, risk, what can be done about it?

I see three approaches:

I. Keep superhuman level AI from being developed.

That might be possible if we had a world government committed to the project but (fortunately) we don’t. Progress in AI does not require enormous resources so there are many actors, firms and governments, that can attempt it. A test of an atomic weapon is hard to hide but a test of an improved AI isn’t. Better AI is likely to be very useful. A smarter AI in private hands might predict stock market movements a little better than a very skilled human, making a lot of money. A smarter AI in military hands could be used to control a tank or a drone, be a soldier that, once trained, could be duplicated many times. That gives many actors a reason to attempt to produce it.

If the issue was building or not building a superhuman AI perhaps everyone who could do it could be persuaded that the project is too dangerous, although experience with the similar issue of Gain of Function research is not encouraging. But at each step the issue is likely to present itself as building or not building an AI a little smarter than the last one, the one you already have. Intelligence, of a computer program or a human, is a continuous variable; there is no obvious line to avoid crossing.

When considering the down side of technologies–Murder Incorporated in a world of strong privacy or some future James Bond villain using nanotechnology to convert the entire world to gray goo – your reaction may be “Stop the train, I want to get off.” In most cases, that is not an option. This particular train is not equipped with brakes. (Future Imperfect, Chapter II)

II. Tame it, make sure that the superhuman AI is on our side.

Some humans, indeed most humans, have moral beliefs that affect their actions, are reluctant to kill or steal from a member of their ingroup. It is not absurd to belief that we could design a human level artificial intelligence with moral constraints and that it could then design a superhuman AI with similar constraints. Human moral beliefs apply to small children, for some even to some animals, so it is not absurd to believe that a superhuman could view humans as part of its ingroup and be reluctant to achieve its objectives in ways that injured them.

Even if we can produce a moral AI there remains the problem of making sure that all AI’s are moral, that there are no psychopaths among them, not even ones who care about their peers but not us, the attitude of most humans to most animals. The best we can do may be to have the friendly AIs defending us make harming us too costly to the unfriendly ones to be worth doing.

III. Keep up with AI by making humans smarter too.

The solution proposed by Raymond Kurzweil is for us to become computers too, at least in part. The technological developments leading to advanced A.I. are likely to be associated with much greater understanding of how our own brains work. That might make it possible to construct much better brain to machine interfaces, move a substantial part of our thinking to silicon. Consider 89352 times 40327 and the answer is obviously 3603298104. Multiplying five figure numbers is not all that useful a skill but if we understand enough about thinking to build computers that think as well as we do, whether by design, evolution, or reverse engineering ourselves, we should understand enough to offload more useful parts of our onboard information processing to external hardware.

Now we can take advantage of Moore’s law too.

A modest version is already happening. I do not have to remember my appointments — my phone can do it for me. I do not have to keep mental track of what I eat, there is an app which will be happy to tell me how many calories I have consumed, how much fat, protein and carbohydrates, and how it compares with what it thinks I should be doing. If I want to keep track of how many steps I have taken this hour3 my smart watch will do it for me.

The next step is a direct mind to machine connection, currently being pioneered by Elon Musk’s Neuralink. The extreme version merges into uploading. Over time, more and more of your thinking is done in silicon, less and less in carbon. Eventually your brain, perhaps your body as well, come to play a minor role in your life, vestigial organs kept around mainly out of sentiment.

As our AI becomes superhuman, so do we.

March 31, 2024

QotD: Sins and “sins”

While true of the puritanical organic lobby, a Supersized ethical position is also advanced by all too many Christians. Indeed, this is where the green-thinkers derive their theology in the first place. Gluttonous McDonald’s visits are on a long list that includes some items mentioned once or twice in scripture such as gay sex, polycotton and women letting their hair down in church and plenty of things from cocaine to coffee which are nowhere to be found in the Bible. The notion is that some things, while pleasurable, will prevent your immortal soul from making it to heaven and that for your own good you must be prevented from enjoying them. That this makes a nonsense of free will, shows precious little faith in the free gift of Grace and that some “sins” are singled out for hysterical attention while most are ignored entirely does not bother puritans historical or contemporary. And the fact most people worship at a different altar altogether does not cross their minds at all.

Ghost of a Flea, “Religion in general”, Ghost of a Flea, 2005-04-13.

March 12, 2024

QotD: Isaiah Berlin on Niccolò Machiavelli

When asked about Machiavelli’s reputation, people use terms like “amoral”, “cynical”, “unethical”, or “unprincipled”. But this is incorrect. Machiavelli did believe in moral virtues, just not Christian or Humanistic ones.

What did he actually believe?

In 1953, the British philosopher Isaiah Berlin delivered a lecture titled “The Originality of Machiavelli”.

Berlin began by posing a simple question: Why has Machiavelli unsettled so many people over the years?

Machiavelli believed that the Italy of his day was both materially and morally weak. He saw vice, corruption, weakness, and, as Berlin says, “lives unworthy of human beings”. It’s worth noting here that around the time that Machiavelli died in 1527, the Age of Exploration was just kicking off, and adventurers from Italy and elsewhere in Europe were in the process of transforming the world. Even the shrewdest individuals aren’t always the best judges of their own time.

So what did Machiavelli want? He wanted a strong and glorious society. Something akin to Athens at its height, or Sparta, or the kingdoms of David and Solomon. But really, Machiavelli’s ideal was the Roman Republic.

To build a good state, a well-governed state, men require “inner moral strength, magnanimity, vigour, vitality, generosity, loyalty, above all public spirit, civic sense, dedication to security, power, glory”.

According to Machiavelli, these are the Roman virtues.

In contrast, the ideals of Christianity are “charity, mercy, sacrifice, love of God, forgiveness of enemies, contempt for the goods of this world, faith in the hereafter”.

Machiavelli wrote that one must choose between Roman and Christian virtues. If you choose Christianity, you are selecting a moral framework that is not favorable to building and preserving a strong state.

Machiavelli does not say that humility, compassion, and kindness are bad or unimportant. He actually agrees that they are, in fact, good and righteous virtues. He simply says that if you adhere to them, then you will be overrun by more unscrupulous men.

In some instances, Machiavelli would say, rulers may have to commit war crimes in order to ensure the survival of their state. As one Machiavelli translator has put it: “Men cannot afford justice in any sense that transcends their own preservation”.

From Berlin’s lecture:

If you object to the political methods recommended because they seem to you morally detestable … Machiavelli has no answer, no argument … But you must not make yourself responsible for the lives of others or expect good fortune; you must expect to be ignored or destroyed.

In a famous passage, Machiavelli writes that Christianity has made men “weak”, easy prey to “wicked men”, since they “think more about enduring their injuries than about avenging them”. He compares Christianity (or Humanism) unfavorably with Paganism, which made men more “ferocious”.

“One can save one’s soul,” writes Berlin, “or one can found or maintain or service a great and glorious state; but not always both at once.”

Again, Machiavelli’s tone is descriptive. He is not making claims about how things should be, but rather how things are. Although it is clear what his preference is.

He writes that Christian virtues are “praiseworthy”. And that it is right to praise them. But he says they are dead ends when it comes to statecraft.

Machiavelli wrote:

Any man who under all conditions insists on making it his business to be good, will surely be destroyed among so many who are not good. Hence a prince … must acquire the power to be not good, and understand when to use it and when not to use it, in accord with necessity.

To create a strong state, one cannot hold delusions about human nature:

Everything that occurs in the world, in every epoch, has something that corresponds to it in the ancient times. The reason is that these things were done by men, who have and have always had the same passions.

Rob Henderson, “The Machiavellian Maze”, Rob Henderson’s Newsletter, 2023-12-09.

February 14, 2024

QotD: Judging historical figures’ actions

It is important to judge people and events in their own time. First, because that’s the only way we really can judge them.

You can’t judge people on actions they didn’t know were wrong, or on things that were hidden from them, which only time has revealed. Or rather, you can, but it’s deranged. What you are holding people guilty of is not being psychic. Not being able to foretell the future. Well, none of us can. Not with any accuracy, and never about things we want to. (Yeah, sometimes I get something like glimpses, but seriously? Do you see me among the lottery winners? No? That’s because I can’t see the future in a significant way.) Go ahead and despise people for that failing, but be aware you’re being deranged.

Also, unlike the people on the left, most of us are aware we, ourselves, are not infallible, and our time is not the pinnacle of knowledge and morality. Things that seem right to us now — or at least not markedly wrong — can and will be reviled by future lovers of liberty.

Sarah Hoyt, “In Their Time”, According to Hoyt, 2023-11-07.