About a week ago, I linked to Alex McColl’s argument for splitting the Royal Canadian Air Force’s new fighter program into a small tranche of F-35s (because we’d already paid for the first 16 of an 88-plane order) and a much larger number of Swedish Gripen fighters from Saab, which on paper would give the RCAF enough aircraft to simultaneously meet our NATO and NORAD commitments. In the National Post, Andrew Richter makes the case to stick with the original plan, pointing to Canada’s truly horrifying history of cancelled military equipment and the costs of running two completely different fighter aircraft:

Canada does not have a very good track record when it comes to cancelling military contracts. About 30 years ago, the Liberal government of Prime Minister Jean Chrétien decided to cancel a contract that the Mulroney government had negotiated to purchase helicopters from a European consortium. Chrétien likened the new aircraft to a “Cadillac”, and maintained that our existing helicopters, the venerable Sea Kings, were still airworthy (despite their advancing age).

So the contract was torn up and the Canadian government paid a total of $500 million in cancellation fees. It would be another decade before a replacement helicopter was finally purchased (the American-made CH-148 Cyclones), and it was only in 2018 that the last Sea King was retired from service. The whole episode has been described by more than one observer as the worst defence procurement project in history. Which brings us to the tortured history of the F-35 purchase.

There is no need here to review the astonishing array of twists and turns that have taken place over the past few decades with regards to it. Suffice to note that when the F-35 contract was signed a few years ago, numerous defence analysts were in disbelief; many had long since concluded that it would never happen, and that Canada would continue flying our CF-18s until they literally could not fly anymore.

Any decision at this point to overturn the contract and go with the second-place finisher in the fighter jet competition — the Swedish Gripen — would have serious consequences. First, as with the helicopter cancellation decades ago, there will likely be financial penalties to pay, although so far the government has not commented on this.

In addition, a decision to buy the Gripen would mean that our Armed Forces would operate two fighter jets moving forward, because the first tranche of 16 F-35s is already bought and paid for. This would necessitate a wide range of additional costs, including training, maintenance and storage. Over decades, these costs would add billions (likely tens of billions) to the defence budget.

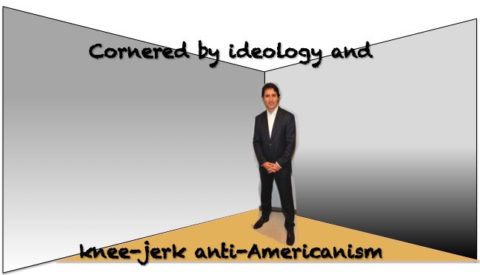

There are also issues of bilateral military co-operation, potential loss of affiliated contracts and force inter-operability to consider. The Canadian military has been primarily buying American military equipment for decades. This has been done both because our military generally prefers U.S. equipment and because it helps strengthen defence ties between our two countries. Deciding to buy a foreign aircraft would jeopardize these ties.