Tim Worstall, in refuting something being pushed by Willie Hutton, explains how the British government escaped from the Great Depression and set off a nice little boom in the mid- to late-1930s:

Well, yes. Except that’s not actually what did drag Britain out of the Depression. What did was expansionary fiscal austerity. You know, that thing the Tories talked of in 2010 and which everyone laughed at? Somewhat annoyingly I was one of the very few (it’s annoying because I was clearly right in what I was saying) who pointed this out back then.

When we boil this right down it’s an argument about the effectiveness of monetary policy. Absolutely no one thinks that it has no effect. But there’s many who think that it has no effect at the zero lower bound: when interest rates are zero. That’s really the argument that leads to fiscal policy, that idea that government might tax less, or spend more, blow out that deficit and get the economy moving again. We’ve done all we could with monetary policy and we’ve still got to do something so here’s fiscal policy.

To put it as simply as possible. We’ve two major macroeconomic tools, monetary policy and fiscal. The first is interest rates, exchange rates and money printing and so on. The second is the difference between taxes collected and money spent by government — the government deficit or surplus (note, please, for purists, this is being very simple).

OK, either lever or tool can be used to loosen conditions — gee stuff up — or tighten them. Which we use when is somewhere between a matter of taste and necessarily correct given the circumstances. But clearly the total amount of geeing up out of a recession — or tightening to prevent inflation — or depression is the combination of the two sets of policies, applications of levers and tools.

It’s thus theoretically possible to tighten with one, loosen with the other and gain, overall, either tightening or loosening. Depends upon how much of each you do.

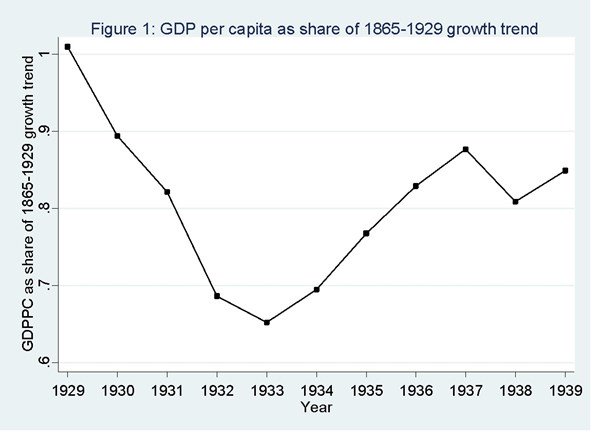

Britain in the 30s tightened fiscal policy. The opposite of what the Keynesians said, the opposite of what the US did and so on. Cut — no, really cut, not just slowed the increase in — government spending and thereby cut the government deficit (might, actually, have gone into surplus, not sure). This is, according to the Keynesian line, something that should make the recession/depression worse.

But at the same time they came off the gold standard — Churchill had taken us back in in 1925 at far too high a rate — and lowered interest rates. That’s a loosening of monetary policy.

As it happens, on balance, the monetary was loosened more than the fiscal was tightened and so we have expansionary fiscal austerity. Which set off a very nice little boom in fact. The mid- to late- 30s in Britain were economic good times. Driven, nicely driven, by a housebuilding boom — the last time the private sector built 300 k houses a year in fact (this is before the Town and Country Planning Act stopped all that). Mixed in was that the motor car was becoming a fairly standard bourgeois item and so housing spread out along the roads.