In the latest book review from Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, Jane Psmith discusses A Field Guide to American Houses (Revised): The Definitive Guide to Identifying and Understanding America’s Domestic Architecture, by Virginia Savage McAlester. In particular, she looks at McAlester’s coverage of how suburbs developed:

After some brief but interesting discussion of cities,1 most of the page count is devoted to the suburbs. It’s a sensible choice: suburbs have by far the most varied types of house groupings, and more than half of Americans live in one. But what exactly is a “suburb”? It’s a wildly imprecise word, referring to anything that is neither truly rural nor the central urban core, and suburbs vary tremendously in character. As a working definition, though, a suburb is marked by free-standing houses on relatively larger lots. (If you can think of a counter-example that qualifies but is “urban”, I’ll bet you $5 it started out as a suburb before the city ate it.)

This means that building a suburb has a few obvious technological prerequisites, which McAlester lists as follows: First, balloon-frame construction, which enabled not just corners but quick and inexpensive construction generally and removed much of the incentive for the shared walls that were so common in the early cityscape. Second, the proliferation of gas and electric utilities in the late nineteenth century meant that the less energy-efficient free-standing homes could still be heated relatively inexpensively. Third, the spread of telephone service after 1880 meant that it was much easier to stay in touch with friends whose front doors weren’t literally ten feet away from yours.2 But by far the most important technological advances came in the field of transportation, which is obviously necessary if you’re going to live in the country (or a reasonable facsimile thereof) and work in the city.

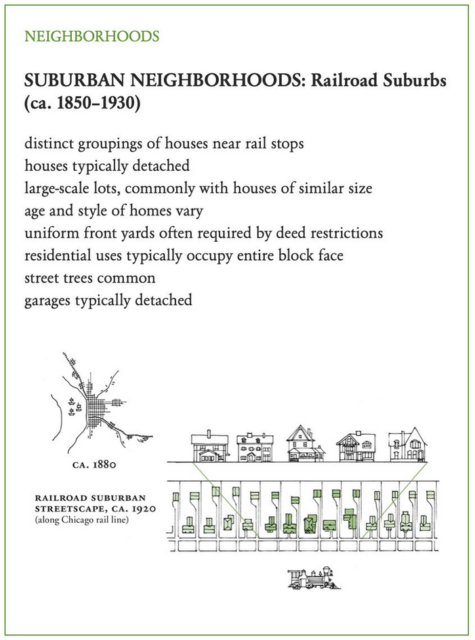

The first of these transportation advances was the railroad. In fact “railroad suburb” is a bit of a misnomer, because most of the collections of houses that grew up around the new rail stops were fully functional towns that had their own agricultural or manufacturing industries. The most famous railroad suburbs, however, were indeed planned as residential communities serving those wealthy enough to pay the steep daily rail fare into the city. Llewellyn Park near New York City, Riverside near Chicago, and the Main Line near Philadelphia are all examples of railroad suburbs that have maintained their tony atmosphere and high property values.

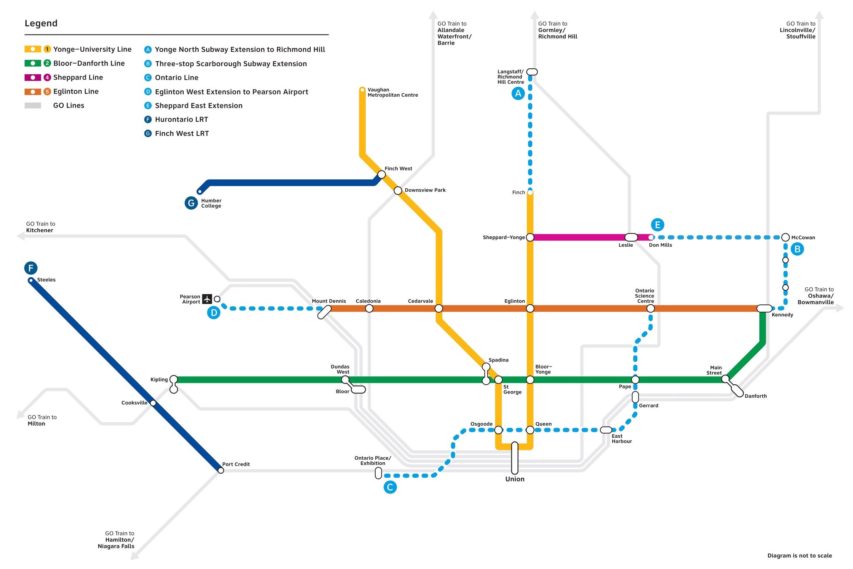

The next and more dramatic change was the advent of the electric trolley or streetcar, first introduced in 1887 but popular until about 1930. (That’s what all the books say, but come on, it’s probably October 1929, right?) Unlike steam locomotives, which take quite a long time to build up speed or to slow down again, and so usually had their stations placed at least a mile apart, streetcars could start and stop far more easily and feature many more, and more densely-placed, stops. Developers typically built a streetcar line from the city veering off into the thinly-inhabited countryside, ending at an attraction like a park or fairground if possible. If they were smart, they’d bought up the land along the streetcar beforehand and could sell it off for houses,3 but either way the new streetcar line added value to the land and the development of the land made the streetcar more valuable.

You can easily spot railroad towns and streetcar suburbs in any real estate app if you filter by the date of construction (for railroad suburbs try before 1910, for streetcar before 1930) and know what shapes to look for. Railroad towns are typically farther out from the urban center and are built in clusters around their stations, which are a few miles from one another. Streetcar suburbs, by contrast, tend to be continuous but narrow, because the appeal of the location dropped off rapidly with distance from the streetcar line. (Lots are narrow for the same reason — to shorten the pedestrian commute.) They expand from the urban center like the spokes of a wheel.

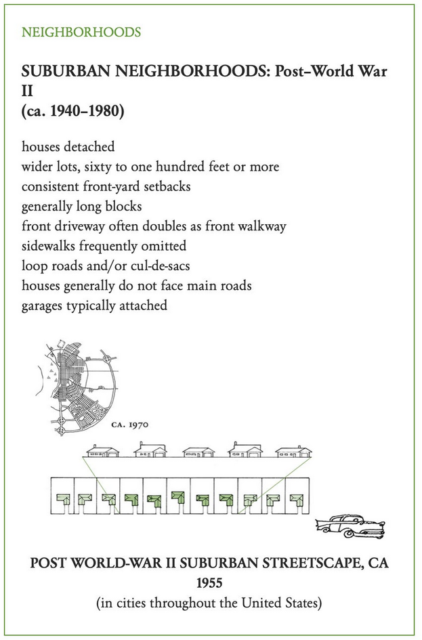

And then came the automobile and, later, the federal government. The car brought a number of changes — paved streets, longer blocks, wider lots (you weren’t walking home, after all, so it was all right if you had to go a little farther) — but nothing like the way the Federal Housing Authority restructured neighborhoods.

The FHA was created by the National Housing Act of 1934 with the broad mandate to “improve nationwide housing standard, provide employment and stimulate industry, improve conditions with respect to mortgage financing, and realize a greater degree of stability in residential construction”. It was a big job, and the FHA set out to accomplish it in a typical New Deal fashion: providing federal insurance for private construction and mortgage loans, but only for houses and neighborhoods that met its approval. This has entered general consciousness as “redlining”, after the color of the lines drawn around uninsurable areas (typically old, urban housing stock),4 but the green, blue, and yellow lines — in order of declining insurability — were just as influential on the fabric of contemporary America.

A slow economy through the 1930s and a prohibition on nonessential construction during the war meant that FHA didn’t have much to do until 1945, but as soon as the GIs began to come home and take advantage of their new mortgage subsidies, there was a massive construction boom. With the FHA insuring both the builders’ construction loans and the homeowners’ mortgages, nearly all the new neighborhoods were built to the FHA’s exacting specifications.

One of the FHA’s major concern was avoiding direct through-traffic in neighborhoods. Many post-World War II developments were built out near the new federally-subsidized highways on the outskirts of the cities, so the FHA was eager to protect new subdivisions from heavy traffic on the interstates and the major arterial roads. Neighborhoods were meant to be near the arterials, but with only a few entrances to the neighborhood and many curved roads and culs-de-sac within it. Unlike the streetcar suburbs or the early automobile suburbs that filled in between the “spokes” of the streetcar lines, where retail had clustered near the streetcar stops, the residents of the post-World War II suburbs found their closest retail establishments outside the neighborhood on the major arterial roads. Lots became wider, blocks longer, and sidewalks less frequent; houses were encouraged to stay small by FHA caps on the size of loans. And although we tend to assume they were purely residential areas, the FHA encouraged the inclusion of schools, churches, parks, libraries, and community centers within the neighborhood.

1. America doesn’t have many urban neighborhoods that predate 1750, and even fewer that persist in their original layout, but if you’ve ever visited one it’s amazing how compact everything feels even in comparison to the rowhouses of the following century.

2. McAlester’s footnote for the paragraph that contains all this reads: “These three essentials were highlighted in an essay the author has read but has not been successful in locating for this footnote.”

3. This is still, I am told, how some of the more sensibly-governed parts of the world run their transit systems: whatever company has the right to build subways buys up the land around a planned (but not announced) subway line through shell corporations, builds the subway, then sells or develops the newly-valuable property. Far more efficient as a funding mechanism than fares!

4. This 2020 NBER working paper points out that redlined areas were 85% white (though they did include many of the black people living in Northern cities) and suggests that race played very little role in where the red lines were drawn; rather, black people were already living in the worst neighborhoods.