One of the odder elements of the New Atheist myths about the Great Library is the strange idea that its (supposed) destruction somehow singlehandedly wiped out the (alleged) advanced scientific knowledge of the ancient world in one terrible cataclysm. It doesn’t take much thought, however, to realise this makes absolutely no sense. The idea that there was just one library in the whole of the ancient world is clearly absurd and, as the mentions of other rival libraries above have already made clear, there were of course hundreds of libraries, great and small, across the ancient world. Libraries and the communities of scholars and scribes that serviced them were established by rulers and civic worthies as the kind of prestige project that was seen as part of their role in ancient society and marked their city or territory as cultured and civilised.

The Ptolemies were not the only successors to Alexander who built a Mouseion with a library; their Seleucid rivals in Syria also built one in Antioch in the reigns of Antiochus IX Eusebes (114-95 BC) or Antiochus X Philopater (95-92 BC). Roman aristocrats and rulers also included the establishment of substantial libraries as part of their civic service. Julius Caesar had intended to establish a library next to the Forum in Rome but this was ultimately achieved after his death by Gaius Asinius Pollio (75 BC – 4 AD), a soldier, politician and scholar who retired to a life of study after the tumults of the Civil Wars. Augustus established the Palatine Library in the Temple of Apollo and founded another one in the Portus Octaviae, next to the Theatre of Marcellus at the southern end of the Field of Mars. Vespasian established one in the Temple of Peace in 70 AD, but probably the largest of the Roman libraries was that of Trajan in his new forum beside the famous column that celebrates his Dacian wars. As mentioned above, this large building probably contained around 20,000 scrolls and had two main chambers – one for Greek and the other for Latin authors. Trajan’s library also seems to have established a design and layout that would be the model for libraries for centuries: a hall with desks and tables for readers with books in niches or shelves around the walls and on a mezzanine level. Libraries also came to be established in Roman bath complexes, with a very large one at the Baths of Caracalla and another at the Baths of Diocletian.

Several of these libraries were substantial. The Library of Celsus at Ephesus was built in c. 117 AD by the son of Tiberius Julius Celsus Polemaeanus in honour of his father, who had been a senator and consul in Rome, and its reconstructed facade is one of the major archaeological features of the site today. It was said to be the third largest library in the ancient world, surpassed only by the great libraries of Pergamon and Alexandria. The Great Library of Pergamon was established by the Attalid rulers of that city state and it was the true rival of the library of the Alexandrian Mouseion. It is said that the Ptolemies were so threatened by its size and the reputation of its scholars that they banned the export of papyrus to Pergamon, causing the Attalids to commission the invention of parchment as a substitute, though this is most likely a legend. What is absolutely clear, however, is that the idea that the Great Library of Alexandria was unique, whether in nature or even in size, is nonsense.

The weird idea that the loss of the Great Library was some kind of singular disaster is at least partially due to the fact that none of the various other great libraries of the ancient world are known to casual readers, so it may be easy for them to assume it was somehow unique. It also seems to stem, again, from the emphasis in popular sources on the mythical immense size of its collection which, as discussed above, is based on a naive acceptance of varied and wildly exaggerated sources. Finally, it seems to stem in no small part from (yet again) Sagan’s influential but fanciful picture of the institution as a distinctively secular hub of scientific research and, by implication, technological innovation.

Tim O’Neill, “The Great Myths 5: The Destruction Of The Great Library Of Alexandria”, History for Atheists, 2017-07-02.

November 27, 2024

QotD: The Great Library and its competitors

August 25, 2024

Woke libraries

Frank Furedi on the already well-advanced plan to turn public libraries into safe spaces for progressive indoctrination:

In recent times, the Library has become the target of what I characterise in my new book, as The War Against The Past. The current project of dispossessing Western society of its historical legacy has gained a powerful influence over the institutions of culture. That is why the Library – a repository of the knowledge and wisdom gained through the past – has become the target of cultural vandalism.

The promoters of the culture war in the Library often justify their action on the ground that their target is not so much the past – but the “racist past”. This is the argument used by the Government backed supporters of a campaign in Wales who wish to reorganise libraries along the lines of anti-racist principles. These racially obsessed cultural warriors insist that Libraries throughout Wales must embrace the goal of becoming anti-racists if the devolved Labour government’s pledge to “eradicate” systemic racism by 2030 would be realised. To ensure that libraries and the “racist” buildings holding their collection are cleansed of the sin of “whiteness”, a £130,000 project designed to indoctrinate local librarians in “critical whiteness studies” has been devised.

The project of racial indoctrination pursued in Wales warns that staff training sessions will be necessary to ensure that libraries align with anti-racist principles. However, it insists that such training sessions should not take place in buildings with a “racist past”. From the standpoint of the authors of the document proposing “critical whiteness studies”, many buildings housing libraries must be avoided because they serve as symbols of racism. Do they presume that the buildings in question can contaminate members of the public with the racist plague? Or are they merely interested in tearing down the walls of racist buildings in order to rebuild them as temples to the doctrine of decolonization?

In a world, where the racialisation of every dimension of life has acquired its own imperative, it was only a matter of time before buildings became demonised as racist. There is now a veritable literature authored by academic racial entrepreneurs who insist that buildings can be racist. One enthusiastic social scientist supporting this thesis offers numerous “examples of buildings being racist”. The racialisation of building and the material properties used in their construction has acquired the character of a veritable fetish. “Concrete, steel and glass buildings are ‘racist'” is the title of one contribution on this subject.

The Welsh Government appears to be consumed by the quest of ridding its nations of racist buildings. As far back as 2021 it published an audit of all such buildings as well as, schools, streets, statues and pubs that it regarded as the product of Wales’ racist past. In effect almost any building, street name or pub whose name was linked with a historical figure was by definition racist. Gone are the days when a pub is allowed to call itself Admiral Nelson or the Duke of Wellington.

The policy of renaming a building, street or a statue is bad enough. What is far worse is when a library is forced to subordinate its book collection to the imperative of racialization. In the name of ridding the book shelves of their “whiteness” and “racist past”, a library becomes a target of officially sanctioned cultural vandalism.

Throughout the Anglosphere. Cultural vandalism is justified on the ground of settling scores with colonialism, racism or white supremacy. For example, school libraries in Australia have removed “outdated and offensive books on colonialism” from their collection[v]. The purge of a school library in Melbourne was guided by Dr Al Fricker, a Dja Dja Wurrung man and expert in Indigenous education with Deakin University. In the course of auditing all 7000 titles on its library shelves. Fricker showed little nostalgia towards the collection. He stated that some of the books removed were almost 50-year-old and were “simply gathering dust anyway”. He stated that “we wouldn’t accept science books being that old in the library, so why do we accept other non-fiction books to be that old, because nothing is static”.

There is something truly disturbing about the idea that a library ought to rid itself of old non-fiction books. In my discipline of sociology that would mean ridding libraries of the 19th century pioneers of the field. In effect the call to reject old non-fiction books constitutes the annihilation of the intellectual legacy of the social sciences and the humanities.

December 31, 2023

This library has every book ever published

Tom Scott

Published 11 Sept 2023The British Library is one of the six legal deposit libraries for the UK — and the only one that doesn’t pick and choose, or have to ask for copies. That’s a lot of books to store, and the internet’s only making it worse. ■ The BL: https://bl.uk ■ UK Web Archive: https://www.webarchive.org.uk/

(more…)

November 13, 2023

QotD: The “queering-the-museum” movement

The so-called queering-the-museum movement, which was launched in Amsterdam in 2016, is all about contemporary identity politics. It rests on the assumption that museum curation is too “heteronormative”. By queering museum collections, activist curators claim they are including and representing gay and gender non-conforming people.

That at least is the objective. But the actual result is an exercise in narcissism. It turns the past into little more than a mirror reflecting the identitarian obsessions of the present back at us. It tells us less than nothing.

And no wonder. Understanding the past through a “queer” prism is profoundly ahistorical. In the 1500s, “queer” didn’t mean what it does today. It meant “strange, peculiar, odd or eccentric“, and had nothing to do with sexual or gender identity at all. Queer only started to be used as a term for gay men at the turn of the 20th century. And “queer studies” was not named as such until the mid-1990s. Viewing the Mary Rose collection through a “queer” lens is to obscure its historical specificity.

It’s not just the Mary Rose Museum that has succumbed to the cult of queer theory, either. Even more bizarrely, the British Library claimed during Pride month this year that the animal world can be viewed through a queer lens. And so Britain’s national centre of knowledge and learning staged events “celebrat[ing] nature in all its queerness”. In particular, it focussed on animals whose sexual behaviour breaks free from standard “gender roles”, from bisexual penguins and lesbian albatrosses to gender-bending fish. “[Researchers’] discoveries”, stated a press release, “show that animal sexuality is far more diverse than we once thought and has been limited by narrow human stereotypes of heterosexuality, monogamy and gender roles”.

This is obviously absurd. Animals do not experience or possess a sense of identity, sexuality or gender. For a fish to “bend” gender it would need to understand what gender is and how to subvert it – quite an achievement for a creature with a five-second memory recall.

Applying “queer” models to the animal world in this way does a disservice not just to our knowledge of animals, but also to our understanding of humans. Non-human animals aim to remain alive and comfortable and propagate their species. Human sex and sexual identity goes far beyond mere survival and comfort. While there may be many interesting reasons why two female penguins pair off, we can be certain that a sense of lesbian self-identity is not one of them.

As the cases of the Mary Rose Museum and the British Library show, queer methodology does not help us to understand history or nature. This is hardly a surprise. Applying a queer lens to species or epochs where it has no place simply exposes the banality of queer theory. It sees nothing but its own reflection. This narcissistic endeavour is now posing a threat to knowledge itself.

Ann Furedi, “The narcissism of queer theory”, Spiked, 2023-08-12.

September 13, 2023

Michael Geist on the “relentless misinformation campaign that ignores the foundational principles of copyright law”

Michael Geist discusses a recent public statement from the Canadian Federation of Library Associations on how changes to copyright rules in Canada may seriously impact the public:

Last month, the Canadian Federation of Library Associations released a much-needed statement that sought to counter the ongoing misinformation campaign from copyright lobby groups regarding the state of Canadian copyright and the extensive licensing by libraries and educational institutions. I had no involvement whatsoever with the statement, but was happy to tweet it out and was grateful for the effort to set the record straight on what has been a relentless misinformation campaign that ignores the foundational principles of copyright law. Lobby groups have for years tried to convince the government that 2012 copyright reforms are to blame for the diminished value of the Access Copyright licence that led Canadian educational institutions to seek other alternatives, most notably better licensing options that offer greater flexibility, access to materials, and usage rights. This is false, and when the CFLA dared to call it out, those same groups then expressed their “profound disappointment” in the library association.

Yet what has been disappointing is that despite repeated Supreme Court of Canada decisions that have eviscerated the foundation of those groups’ claims, they insist on running back the same failed strategy again and again. The reality of Canadian copyright isn’t complicated: libraries and the education community spend more than ever before on licences that provide the right to access and use materials for teaching, course materials, text and data mining, and a myriad of other purposes. When combined with the gradual disappearance of course packs, the emergence of open access materials, and a reasonable interpretation of fair dealing consistent with Canadian jurisprudence, education and libraries are fulfilling their mandate by responsibly using public dollars to maximize public access, enable student learning, and ensuring fair compensation for authors.

The lobbying efforts to convince government to restrict fair dealing by requiring unnecessary licences would increase student costs, make education less affordable, and render Canada less competitive. Further, it would mean less access to materials for Canadian students. Universities spend hundreds of millions of dollars on licences that grant both access to materials (purchasing physical books has declined dramatically) and the ability to use them. The outdated Access Copyright licences only grant rights to use already acquired works for a limited series of purposes. Reverting back to the unnecessary Access Copyright licence would mean access to fewer works and reduced investment by the education sector and libraries in new works.

I wrote a six-part series on these issues earlier the year including posts on setting the record straight, the shift to electronic licensing, transactional licences, the disappearance of course packs, the emergence of open text books, and a fair reading of fair dealing. Once you get past the rhetoric, the data leaves little doubt that education and libraries are still actively paying for copyright materials through licensing and the claims of mass illegal copying in education in 2023 is a fabrication unsupported by the evidence.

December 18, 2022

QotD: Citation systems and why they were developed

For this week’s musing I wanted to talk a bit about citation systems. In particular, you all have no doubt noticed that I generally cite modern works by the author’s name, their title and date of publication (e.g. G. Parker, The Army of Flanders and the Spanish Road (1972)), but ancient works get these strange almost code-like citations (Xen. Lac. 5.3; Hdt. 7.234.2; Thuc. 5.68; etc.). And you may ask, “What gives? Why two systems?” So let’s talk about that.

The first thing that needs to be noted here is that systems of citation are for the most part a modern invention. Pre-modern authors will, of course, allude to or reference other works (although ancient Greek and Roman writers have a tendency to flex on the reader by omitting the name of the author, often just alluding to a quote of “the poet” where “the poet” is usually, but not always, Homer), but they did not generally have systems of citation as we do.

Instead most modern citation systems in use for modern books go back at most to the 1800s, though these are often standardizations of systems which might go back a bit further still. Still, the Chicago Manual of Style – the standard style guide and citation system for historians working in the United States – was first published only in 1906. Consequently its citation system is built for the facts of how modern publishing works. In particular, we publish books in codices (that is, books with pages) with numbered pages which are typically kept constant in multiple printings (including being kept constant between soft-cover and hardback versions). Consequently if you can give the book, the edition (where necessary), the publisher and a page number, any reader seeing your citation can notionally go get that edition of the book and open to the very page you were looking at and see exactly what you saw.

Of course this breaks down a little with mass-market fiction books that are often printed in multiple editions with inconsistent pagination (thus the endless frustration with trying to cite anything in A Song of Ice and Fire; the fan-made chapter-based citation system for a work without numbered or uniquely named chapters is, I must say, painfully inadequate.) but in a scholarly rather than wiki-context, one can just pick a specific edition, specify it with the facts of publication and use those page numbers.

However the systems for citing ancient works or medieval manuscripts are actually older than consistent page numbers, though they do not reach back into antiquity or even really much into the Middle Ages. As originally published, ancient works couldn’t have static page numbers – had they existed yet, which they didn’t – for a multitude of reasons: for one, being copied by hand, the pagination was likely to always be inconsistent. But for ancient works the broader problem was that while they were written in books (libri) they were not written in books (codices). The book as a physical object – pages, bound together at a spine – is more technically called a codex. After all, that’s not the only way to organize a book. Think of a modern ebook for instance: it is a book, but it isn’t a codex! Well, prior to codex becoming truly common in third and fourth centuries AD, books were typically written on scrolls (the literal meaning of libri, which later came to mean any sort of book), which notably lack pages – it is one continuous scroll of text.

Of course those scrolls do not survive. Rather, ancient works were copied onto codices during Late Antiquity or the Middle Ages and those survive. When we are lucky, several different “families” of manuscripts for a given work survive (this is useful because it means we can compare those manuscripts to detect transcription errors; alas in many cases we have only one manuscript or one clearly related family of manuscripts which all share the same errors, though such errors are generally rare and small).

With the emergence of the printing press, it became possible to print lots of copies of these works, but that combined with the manuscript tradition created its own problems: which manuscript should be the authoritative text and how ought it be divided? On the first point, the response was the slow and painstaking work of creating critical editions that incorporate the different manuscript traditions: a main text on the page meant to represent the scholar’s best guess at the correct original text with notes (called an apparatus criticus) marking where other manuscripts differ. On the second point it became necessary to impose some kind of organizing structure on these works.

The good news is that most longer classical works already had a system of larger divisions: books (libri). A long work would be too long for a single scroll and so would need to be broken into several; its quite clear from an early point that authors were aware of this and took advantage of that system of divisions to divide their works into “books” that had thematic or chronological significance. Where such a standard division didn’t exist, ancient libraries, particularly in Alexandria, had imposed them and the influence of those libraries as the standard sources for originals from which to make subsequent copies made those divisions “canon”. Because those book divisions were thus structurally important, they were preserved through the transition from scrolls to codices (as generally clearly marked chapter breaks), so that the various “books” served as “super-chapters”.

But sub-divisions were clearly necessary – a single librum is pretty long! The earliest system I am aware of for this was the addition of chapter divisions into the Vulgate – the Latin-language version of the Bible – in the 13th century. Versification – breaking the chapters down into verses – in the New Testament followed in the early 16th century (though it seems necessary to note that there were much older systems of text divisions for the Tanakh though these were not always standardized).

The same work of dividing up ancient texts began around the same time as versification for the Bible. One started by preserving the divisions already present – book divisions, but also for poetry line divisions (which could be detected metrically even if they were not actually written out in individual lines). For most poetic works, that was actually sufficient, though for collections of shorter poems it became necessary to put them in a standard order and then number them. For prose works, chapter and section divisions were imposed by modern editors. Because these divisions needed to be understandable to everyone, over time each work developed its standard set of divisions that everyone uses, codified by critical texts like the Oxford Classical Texts or the Bibliotheca Teubneriana (or “Teubners”).

Thus one cited these works not by the page numbers in modern editions, but rather by these early-modern systems of divisions. In particular a citation moves from the larger divisions to the smaller ones, separating each with a period. Thus Hdt. 7.234.2 is Herodotus, Book 7, chapter 234, section 2. In an odd quirk, it is worth noting classical citations are separated by periods, but Biblical citations are separated by colons. Thus John 3:16 but Liv. 3.16. I will note that for readers who cannot access these texts in the original language, these divisions can be a bit frustrating because they are often not reproduced in modern translations for the public (and sometimes don’t translate well, where they may split the meaning of a sentence), but I’d argue that this is just a reason for publishers to be sure to include the citation divisions in their translations.

That leaves the names of authors and their works. The classical corpus is a “closed” corpus – there is a limited number of works and new ones don’t enter very often (occasionally we find something on a papyrus or lost manuscript, but by “occasionally” I mean “about once in a lifetime”) so the full details of an author’s name are rarely necessary. I don’t need to say “Titus Livius of Patavium” because if I say Livy you know I mean Livy. And in citation as in all publishing, there is a desire for maximum brevity, so given a relatively small number of known authors it was perhaps inevitable that we’d end up abbreviating all of their names. Standard abbreviations are helpful here too, because the languages we use today grew up with these author’s names and so many of them have different forms in different languages. For instance, in English we call Titus Livius “Livy” but in French they say Tite-Live, Spanish says Tito Livio (as does Italian) and the Germans say Livius. These days the most common standard abbreviation set used in English are those settled on by the Oxford Classical Dictionary; I am dreadfully inconsistent on here but I try to stick to those. The OCD says “Livy”, by the by, but “Liv.” is also a very common short-form of his name you’ll see in citations, particularly because it abbreviates all of the linguistic variations on his name.

And then there is one final complication: titles. Ancient written works rarely include big obvious titles on the front of them and often were known by informal rather than formal titles. Consequently when standardized titles for these works formed (often being systematized during the printing-press era just like the section divisions) they tended to be in Latin, even when the works were in Greek. Thus most works have common abbreviations for titles too (again the OCD is the standard list) which typically abbreviate their Latin titles, even for works not originally in Latin.

And now you know! And you can use the link above to the OCD to decode classical citations you see.

One final note here: manuscripts. Manuscripts themselves are cited by an entirely different system because providence made every part of paleography to punish paleographers for their sins. A manuscript codex consists of folia – individual leaves of parchment (so two “pages” in modern numbering on either side of the same physical page) – which are numbered. Then each folium is divided into recto and verso – front and back. Thus a manuscript is going to be cited by its catalog entry wherever it is kept (each one will have its own system, they are not standardized) followed by the folium (‘f.’) and either recto (r) or verso (v). Typically the abbreviation “MS” leads the catalog entry to indicate a manuscript. Thus this picture of two men fighting is MS Thott.290.2º f.87r (it’s in Det Kongelige Bibliotek in Copenhagen):

MS Thott.290.2º f.87r which can also be found on the inexplicably well maintained Wiktenauer; seriously every type of history should have as dedicated an enthusiast community as arms and armor history.

And there you go.

Bret Devereaux, “Fireside Friday, June 10, 2022”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-06-10.

June 5, 2022

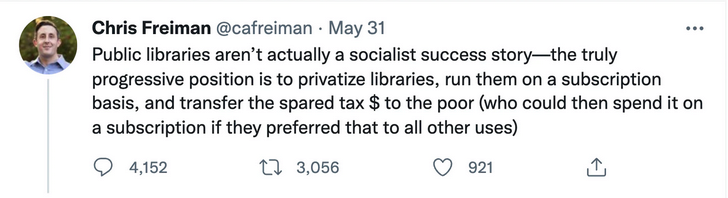

Privatize the libraries?

In the latest SHuSH newsletter, Kenneth Whyte discovers — perhaps to his surprise — he’s not actually the most visible crank on public library issues:

I’m no longer the world’s biggest crank on public libraries. My argument, you’ll recall, is that public libraries are a good thing, but that North Americans borrowing rather than buying three out of every four books they read is a bad thing for the incomes of authors, the economics of publishers, and the welfare of just about everyone else involved in the book industry. That’s fainthearted stuff compared to this week’s tweet from Chris Freiman, a philosophy professor at William & Mary:

As you can guess from the 4,152 comments he’d generated by last night, Freiman’s was an unpopular take. Summing up the responses:

No one has been in a mood to ask if Freiman has a point, or where he’s coming from. For what it’s worth, he has a track record of criticism of government welfare spending. His usual schtick is to ask why so many Americans are poor when the poverty line for a family of three is $18,530 (annually) and welfare spending on a family of three from all three levels of government amounts to $61,830 (annually). It’s not the worst question.

His answer appears to be that directly transferring funds to the poor would be a more effective and efficient way of alleviating poverty than allowing governments to keep running expensive programs that are failing to achieve the same end. That’s not the worst answer.

But does he have a point regarding libraries?

I give him half a point. Public libraries are overwhelmingly used by people who can afford to buy books, and those people are reading primarily for pleasure. I’m all for lending books to people who can’t afford them, who have trouble accessing them, or who want to improve their minds by reading important or serious stuff. But to the extent that libraries are giving middle-class patrons free entertainment—sure, privatize them. There are better uses of public money. Apply the funds to reduce tax burdens on low-income families or improve conditions in government-run nursing homes.

Where the privatization argument fails is that libraries do a lot more than provide middle-class patrons with entertainment. They are important community hubs and for a minority of users they continue to fulfill their original purpose, which, says historian Ed D’Angelo, was to “promote and sustain the knowledge and values necessary for a democratic civilization”. Privatization would likely destroy the valuable public service aspects of public libraries.

In fact, the real problem with public libraries today is that they’re already half privatized. Starting in the middle of the last century, they stopped believing in their role as the community’s edifier-in-chief. They adopted the mindset of the marketplace, giving people what they wanted, filling their shelves with multiple copies of the hottest bestsellers, however vacuous, and measuring their success by counting foot traffic at their branches. They now manage those branches like Walmart supercentres, maximizing transactions per square foot of space. Who cares what patrons are reading, or why, so long as the turnstiles are spinning.

I’d prefer they leave private-sector thinking to the private sector, and let public libraries rebuild their lending practices around their original mission of elevating the minds of citizens. Surely we can’t yet afford to abandon the latter objective.

My solutions to the public library problem, in order of preference, are a much more robust public lending right, an exclusive new release window for the retail trade, and user fees for patrons who can afford them. More discussion here.

In any event, thanks to Professor Freiman for revealing me as a moderate.

January 16, 2022

Library borrowing versus book store sales

I used to be a regular library user, but tapered off substantially after a few unhappy visits to the Toronto Reference Library on Yonge Street in the late ’80s (I’m now fully a believer in some of the wilder tales of disruptive and even criminal behaviour within libraries). I had my doubts about the direction most western library systems chose to concentrate on “popular” books and to get rid of “old” or infrequently borrowed books. It seemed to me that this was an attempt to set up libraries in direct competition with bookstores, and a deliberate act of neglect toward the function of libraries as repositories of valuable but less popular media. In the latest SHuSH newsletter, Kenneth Whyte details a fascinating natural experiment we’ve all be involved in over the last two years that seems to prove that library systems have been, in effect, taking money away from book sellers:

“Toronto Public Library” by Jim of JimOnLight is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Those of you who have been reading SHuSH for a while know that I suspect public libraries are doing harm to the publishing industry and author incomes.

Before the shooting starts, my standard qualifiers: I love libraries; they do a lot of fine work and are crucial civic institutions, running many outstanding programs and providing many necessary services, including the lending of books to children and people who genuinely can’t afford to buy them; I am always in libraries for research and to borrow and read hard-to-find books; I don’t want libraries to go away; I don’t want them harmed; I want their lending practices adjusted before they swallow what’s left of commercial publishing, book retailing, and, along with it, what’s left of author incomes.

By way of background, I’ve written at length in previous newsletters about how public libraries in the last decades of the last century abandoned their traditional role as gatekeepers of the culture, responsible for the moral, intellectual, and aesthetic growth of the public, choosing instead to pander to their patrons. They began pimping the likes of Mickey Spillane and Jacqueline Susann to goose the foot traffic and circulation stats they habitually use to demand of their political masters more funding and better buildings.

Over time, librarians have trained people who can afford to buy books for their own entertainment — the vast majority of library reading is for entertainment — to borrow them instead. Today, three out of four books read in the US and four out of five read in Canada are borrowed, not bought. That is bad for publishing, bookselling, and author incomes.

And then the Winged Hussars Wuhan Coronavirus arrived:

I believe it is self-evident that spending loads of taxpayer money to make the most popular books available at no charge at dozens of points around a city (as well as online) undermines retail sales of books, as it would if the same were done for coffee, running shoes, or Leafs’ tickets.

I have to admit, at the same time, that I’ve lacked hard evidence showing a portion of book borrowing represents lost sales. Nobody has thoroughly researched the question (it certainly isn’t in the interests of libraries to do so). The absence of a smoking gun has made it easy for library defenders to throw up their hands: maybe there’s a relationship, maybe not. People love free shit and will cheerfully strangle good faith to retain access to it.

I’ve tried to devise ways to prove conclusively that libraries are seriously undermining book sales. Maybe some huge experiment where we closed the public libraries in a large jurisdiction and studied what happened to retail book sales. But who was going to organize that? It seemed impossible until COVID-19 stepped up.

Libraries across North America and, indeed, around the world, have been closed, semi-closed, or otherwise limited in their borrowing activities throughout the two-year course of the pandemic. According to Library Journal, total circulation of library materials collapsed by 25.7% in 2020 (notwithstanding a huge spike in e-book borrowing). It looks like physical borrowing fell by roughly half. The 2021 numbers aren’t out yet but individual library reports suggest they will look a lot like 2020.

Meanwhile, over in publishing land, the champagne corks are flying. US book sales, which grew healthily in the first pandemic year 2020, grew again in 2021 and are now 19% ahead of the pre-pandemic year, 2019. All the major publishers have reported smashing sales (attributing the increase to their own genius). All categories are up, including adult fiction (31% over 2019) and adult non-fiction (10% over 2019).

Going by these numbers, it appears that a roughly 25% reduction in library borrowing leads over a two-year period to an increase of 19% in bookselling. I wouldn’t bank on those numbers, or even on the rough proportions, but I think the data demonstrates that when you make books more difficult to borrow for free, people turn more frequently to booksellers.

July 10, 2021

Public libraries or public menaces?

In the latest edition of SHuSH, Kenneth Whyte finds a kindred-ish soul in his concerns about the influence public libraries have had in the last fifty years:

“Toronto Public Library” by Jim of JimOnLight is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

It’s not easy being a crank, isolated from one’s fellow man by unpopular convictions, burdened by the certain knowledge of truths society can’t bring itself to admit.

The loneliness of crankdom can be insupportable. So I was overjoyed this month to run across an excellent book by Ed D’Angelo: Barbarians at the Gates of the Public Library: How Postmodern Consumer Capitalism Threatens Democracy, Civil Education, and the Public Good.

D’Angelo, a Ph.D. in philosophy with a master’s of library and information sciences, was supervising librarian at the Brooklyn Public Library for more than twenty years. His politics are not altogether mine (he leans Marxist), and his prose is not what you’d call smooth, but we are in total agreement that public libraries went off the rails sometime in the 1960s and now menace much that is good in life.

If you’re new to this space, you might have missed me mentioning here and there that increasingly aggressive lending practices by public libraries are undermining the entire bookselling ecosystem; that three times as many books are borrowed as bought in the US on an annual basis (four times as many in Canada); that libraries are putting booksellers out of business by advertising how much people can save by borrowing rather than buying books; that most library borrowing is done by people who can afford to pay for books, and who are reading for entertainment, not edification; and that all of this free-and-for-pleasure borrowing is a major reason author incomes are at record lows.

[…]

An honest scholar, Ed notes that there were cracks in this foundation before the 1960s. Back at the turn of the twentieth century, none other than Melvil Dewey, inventor of the Dewey Decimal System and founding member of the American Library Association, dissented from the notion that librarians should instill their values in patrons by directing their reading. He wanted a more mechanical, frictionless distribution of books, and encouraged the hiring of women as librarians on the assumption that they would be less inclined to impose their standards on others.

(Melvil […] was a devil, according to his biographer Wayne Wiegand. He subjected female subordinates to unwanted touching and kissing, and was rumored to have asked them to put their bust sizes on application forms. Forced out of the ALA for sexual harassment, Dewey further distinguished himself as racist and anti-semite. Yet his name was attached to the ALA’s highest honor until 2019.)

Ed also notes that there were stocks of popular (i.e., unedifying) literature in most public libraries even in the early years, but these were intended as the first rung on a ladder of development that “ascended toward the classics of western civilization.”

Starting in the 1960s, writes Ed, that the distribution of popular literature became an end in itself for the public library. Librarians lost confidence or interest in their mission of encouraging enlightened citizenship. They abandoned their role as gatekeepers. It was suddenly square to impose standards or tastes on patrons.

May 1, 2021

When the libraries failed

In another of a series of book reviews by Astral Codex Ten readers, Scott Alexander posted this review of Double Fold by Nicholson Baker, which helps to indicate just when libraries — and librarians — lost their mojo:

“Nottingham central library” by JuliaC2006 is licensed under CC BY 2.0

If you enter a major research library in the US today and request to see a century-old issue of a major American newspaper, such as Chicago Tribune, The Wall Street Journal, or major-but-defunct newspapers such as the New York “World”, odds are that you will be directed to a computer or a microfilm reader. There, you’ll get to see black-and-white images of the desired issue, with individual numbers of the newspaper often missing and much of the text, let alone pictures, barely decipherable.

The libraries in question mostly once had bound issues of these newspapers, but between the 1950s and the 1990s, one after another, they ditched the originals in favor of expensive microfilmed copies of inferior quality. They continued doing this even while the originals became perilously rare; the newspapers themselves were mostly trashed, or occasionally sold to dealers who cut them up and dispersed them. As a consequence, many of these publications are now rarer than the Gutenberg Bible, and some 19th and 20th century newspapers have ceased to exist in a physical copy anywhere in the world.

When Double Fold by Nicholson Baker came out in 2001, it was described as The Jungle of the American library system. After 20 years, the book remains universally known, sometimes admired but often despised, among librarians. The reason for their belligerence is that Baker publicly revealed a decades-long policy of destruction of primary materials from the 19th and 20th centuries, based on a pseudoscientific notion that books on wood-pulp paper are quickly turning to dust, coupled with a misguided futuristic desire to do away with outdated paper-based media. As a consequence, perfectly well preserved books with centuries of life still ahead of them were hastily replaced with an inferior medium which has, at the moment that I am writing this review, already mostly gone the way of the dodo. Despite its notoriety among librarians, however, Double Fold is little-known among the general public, even compared to Baker’s other non-fiction and his novels.

This is a shame, since the mass destruction of books and newspapers by libraries in the post-war era deserves to be better known as one of the most egregious failures of High Modernism, comparable with the wackiest plans of Le Corbusier. The story combines an excessive reliance on simplistic mathematical models, wilful ignorance to the desires of actual library-users and scholars, embracement of miniaturization and modernization as terminal values, and an almost complete disregard of 19th century books as historical artefacts. Unlike industrial farms, which can be broken up, and Brasília-style skyscrapers, which can be torn down and replaced with something else, the losses caused by the mass deaccessioning of books and newspapers from libraries were often irreplaceable.

As part of the uproar that followed the book’s publication, the Association of Research Libraries published an online anti-Baker FAQ, and in 2002, the book Vandals in the Stacks? by Richard J. Cox came out, presenting an attempted refutation of Baker’s theses. I have read both of these and discuss Cox’s arguments later on, but I must admit in advance that I was mostly convinced by Baker’s argumentation much more than by that of his opponents. Nonetheless, it is uncommon to have a polemical book receive a book-length response, and anyone interested in Baker’s thesis is advised to check out Cox as well.

October 23, 2020

The British Library goes “woke”

David Warren views this development with alarm and disdain:

Did you know? That, “Racism is the creation of white people”?

Of course you did, if you are young, woke, and poorly educated, like the white woman who is now the British Library’s Chief Librarian. (“Liz Jolly.”) Her statement, in a video to staff last summer, promoting her Decolonizing Working Group, though perfectly acceptable to Guardian subscribers, was mocked by several African and Asiatic scholars who have depended upon that library’s resources over the years. Noting that history is more complicated than Ms Jolly was ever told, they criticized her as “pig ignorant,” &c.

But her explicitly racist “anti-racist” programme proceeds, with aggressive “anti-racist” exhibitions, new “anti-racist” signage, and so forth. The demand to de-acquisition authors who do not reinforce the current ideological stereotypes has not yet gathered to full force, but has started.

The capture of essentially all major cultural institutions by unhinged political fanatics with daddy issues, is among the signs of our times. Those who resist are driven out of employment; those who accede have a lock on the splendidly-paid positions, for which beleaguered taxpayers are billed. The consequences to Western Civ are not trifling.

Perhaps I am unfair to single out just the one career arts bureaucrat, when there are thousands to choose from. I may even be prejudiced, not only against white people, but against those of the scheduled races who have cooperated in trashing the institutional heritage of the Big Wen.

For London was my Athens, back in the day, and I take these things personally. My British Museum Library ticket was among my most cherished possessions, and the old Reading Room among my favourite haunts. I am now so old that I can remember when such places were ruled, and staffed, by respectably boring establishment types with Oxbridge degrees.

In a different context, we’ve seen just how eager Oxbridge types of the 1930s were eager to join the Soviet spy networks, so the change in establishment staff at non-explicitly communist establishments was only a matter of time…

March 7, 2020

KidLit is woke, woke, woke

Ed West on the amazing amount of propaganda that has been pumped into books for children:

“New Spin on YA” by Salem (MA) Public Library is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

When my daughters were around six and seven, they started French classes at a children’s library in our borough; I had been to our local library countless times but had mainly confined myself to the infant section, and older children’s books were something of a revelation. The entire front desk area was made up of hagiographies of Barack Obama and Nelson Mandela.

And hagiography is the most accurate term: these books were just like the ones I used to read in church. Here Blessed Nelson forgave his jailors, here St Barack healed America of its racial sins – and these are just a couple of examples.

It was a bit of a surprise — learning just how much the tone of kids’ books had changed since I was young and we wore onions on our belts. Nowadays, progressive politics is ever-present in children’s books. Which is fine, if you’re a believer; but if you’re a conservative, you’re faced with raising your children in a culture which is filled with messages you disagree with — sometimes misleading, sometimes anecdotally true but not representative, often just anti-wisdom, giving children the worst possible advice in life. And it’s becoming worse: since about 2016, children’s books have grown way more explicitly political.

Last month, a friend went to Tate Modern and took a picture of the young children’s section. Among the books on display are biographies of Greta Thunberg, something called Queer Heroes, another work called The Rainbow Flag, books about refugees, the bestselling Good Night Book for Rebel Girls — and its countless imitators. Whether you support it or not, this is propaganda; the aim is to raise a generation of progressives just as those Lives of the Saints were designed to bring forth young Christians.

And it works. Conservative ideas are very much in retreat, the subject of a brilliant new book I recently read (which, admittedly, I also wrote).

From a very young age, children are read books and shown films that teach them the core progressive messages: that we are all basically good and only behave badly because of circumstances; that borders and barriers are bad, stereotypes are wrong and girls ought to adopt traditional male gender roles if they want to be respected.

Stereotype inaccuracy is a popular idea — and a false one; in so many kids’ stories the unusual stranger or alien or wild animal who turns up in the neighbourhood will defy the small-minded pessimist who expects the worst. When it comes to gender politics, no self-respecting children’s book in the 21st century has girls aspiring towards being a princess and living happily ever after; to the post-ironic upper-middle-class parents who are the publishers’ main audience, that would just be lame.

March 6, 2020

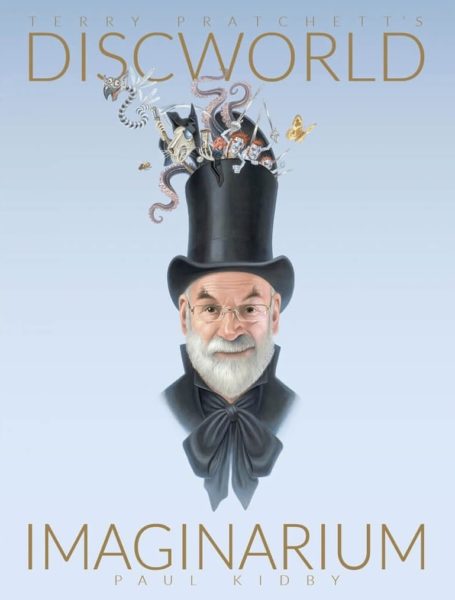

Some of the early influences on Terry Pratchett’s writing

That is, the books that made him love reading and how he incorporated those early works into his own style. This is from a very late interview with Tom Chivers published after his death in 2015:

“I wasn’t particularly interested in books,” he says. “And my mum, God bless her, she rolled up her sleeves and gave me a penny per page, and it worked beautifully. I think she only gave me about thruppence, because the third book was The Wind in the Willows.” He was so enthused after this, she no longer needed to pay him. Indeed, Pratchett got a job in Beaconsfield library. “You’re talking to a man who thinks, mostly, that his school days assisted him not at all, but the library did, in spades.” He looks at me sharply. “You, when you were young, read lots of books, didn’t you? A –” he pauses, and chooses his next word carefully – “a —-load, I believe?” I did, I reassure him. “A library boy. I recognise the kind. I was the same.” He had an indifferent time at school – he grumbles about the “death or glory” nature of the 11-plus (he passed easily), and about old teachers who had a grudge against him at the High Wycombe Technical High School (“sort of half a grammar school. A big woodwork place”). But the fire kindled by Kenneth Grahame, and Ratty, Mole and Badger, grew, and blazed.

Pratchett’s own sense of humour, a sort of gentle, English, observational thing, stems from this period. “Wodehouse, obviously, but also I tore my way through the Just William books. Richmal Crompton was a very good writer. I think it was from her that I learnt irony. It took me a while to work it out.” Do you think you could define irony, I ask him. “Sort of like iron.” I deserved that, I acknowledge. “When you get hit on the head with it, you know it.”

He also fell in love with RJ Yeatman and WC Sellar, authors of 1066 and All That (“in the Thirties, when the middle classes were getting richer, the two of them really got as much fun out of that as you could. The Thirties were an awful lot of fun. Or at least until the end. Bad ending, the decade, admittedly”) and fell out with his headmaster for “bringing in a copy of Mad magazine. How horrible! And a copy of Private Eye. Seditious.” But it was the now defunct satirical magazine Punch which really formed the comic voice in which he now speaks. “I read my way through all the bound Punches. It was the best way to read history; you got it without granny looking over your shoulder, and it was just astonishing.

“And just about any writer of distinction, anywhere in the English language, worked for Punch. Mark Twain. Jerome K Jerome. And they spoke with the same voice, which opened the door for me – the same kind of slightly satirical, people-are-rather-silly-but-they’re-not-that-bad voice, friendly about humanity, fond of its foibles.” Apart from the books, the other influences of his youth are clear in his own writing – especially the later Ankh-set works, in which he frequently extols the virtues of the poor-but-respectable people living in tiny, tidy terraced houses, and of the self-made men and women. “There used to be a sort of dignity in labour,” he says. “I don’t think there is now.”

He has spoken, often, of how his time on local newspapers made him. He started at 16, in high dudgeon at his headmaster: “On my last day at the school, I left all my stuff behind and phoned up the editor of a local newspaper. He actually used some cliché like, ‘I like the cut of your jib, young man’, or something.” It is the stuff of legend that he saw his first dead body the next day, “work experience really meaning something in those days”, as he put it in his author’s bio in his books.

“Truthfully, without over-egging it, as I often do,” he says, “the library and journalism, those things made me who I am. Journalism makes you think fast. You have to speak to people in all walks of life. Especially local journalism. London journalism can p— in someone’s face and they can’t do anything about it. Try that in local journalism, and someone’s down to complain. Everyone should have one local journalism job in their lives, especially if they’re a nosy parker.” He talks of local journalists in the same way he does his parents, with a sense of quiet heroism. “I interviewed an elderly journalist who’d worked in a small town for a very, very long time. I asked: is it boring? And he said: over there, that’s where a couple pushed their daughter into the attic because she’d had a black baby. And over there, that’s where a man was caught in flagrante delicto with a barnyard fowl. And he’d said to the magistrates, ‘Well, it was my fowl’. Even those small moments, they make you realise the world is not as you thought.”

January 31, 2020

The little-known golden age of “The Xeriffe” in the 17th century

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes discusses the economic snapshot of 17th century Europe (and parts of the wider world) provided in the work of Giovanni Botero:

… I’ve spent the past couple of days reading the work of an Italian geographer, Giovanni Botero. His 1590s treatise, on The Strength of all the Powers of Europe and Asia (translated into English in 1601 as The Traveller’s Breviat) tries to provide a comprehensive account of the relative strengths of all the world’s great powers. It can be a bit dry — at times it’s a bit like reading a table of statistics, but in paragraph form, as he goes through every country’s population, geography, and industries, as well as their manpower, the sizes and qualities of their armies and navies, their political systems, taxes, and geopolitical situations. Yet in all that information, we get a snapshot of what characteristics stood out internationally, at a point that was midway through England’s crucial century of change.

I thought I had a pretty good general grasp of the economic history of Europe and the west in the post-Middle Ages period, but Anton mentions something I didn’t know anything about:

Yet there was another region that Botero singled out in terms of its technological and economic achievements, which I had never heard mentioned before: the land of “The Xeriffe”.

The term is usually rendered as sharif, denoting a descendant of the Prophet Muhammad via his grandson, Hasan ibn Ali. In 1600, the title was claimed by the rulers of the Saadi Empire, centred around Fez, in present-day Morocco. Botero claimed that its cities were of marble and alabaster, decorated with great lamps of brass. In Fez in particular were “200 schools of learning, 200 inns, and 400 water mills, every one driven with four or five wheels”, from which the ruler derived a substantial rent. The city also featured “600 conduits, from whence almost every house is served with water.” Indeed, he noted that “the inhabitants are very thrifty, given to traffic [commerce], and especially to the making of clothes of wool, silk, and cotton.”

So here was a remarkable city. One that was wealthy, populous, somewhat industrialised, and given to trade. It was a centre of learning for the entire region, especially under the long rule of one of its sultans, Ahmad al-Mansur “the Golden” and his immediate successors: the library they amassed forms one of the major surviving collections of Islamic manuscripts on literature and science (which was captured during a war in the seventeenth century, and has been in Spain ever since). The Saadi Empire even had some military might: during its rise it successfully contended with Portugal, and it had a large arsenal of gunpowder weapons, which it put to use in conquering parts of Sub-Saharan Africa. It maintained friendly commercial and diplomatic links with both England and the Dutch Republic, uniting with them in their opposition to Spain.

And yet, the Saadi Empire is never mentioned as an efflorescence [defined as “temporary bubblings up of innovation and economic growth, which ultimately resulted in stagnation or decline”]. It doesn’t even feature in debates about the causes of the Long Divergence — the centuries-long reversal of economic fortunes between northwestern Europe and the Islamic world. The latest major book on the reversal, by Jared Rubin (which is excellent, by the way), is entirely devoted to comparisons with the Ottoman Empire, not discussing Morocco even once. That may just be a product of which sources are most readily available in English, or because there are currently quite a few excellent Turkish economic historians, like Şevket Pamuk or Timur Kuran. It’s also possible that the descriptions of Fez’s wealth were exaggerated, or that there are straightforward explanations for its relative economic decline. But, if we’re to fully understand the causes of the Industrial Revolution in Britain, I think the rise and fall of the Saadi Empire is another efflorescence we need to seriously consider.

January 20, 2020

A Drag Queen speaks out against Drag Queen Story Hour for kids

Libby Emmons reports on a rare bird indeed — a Drag Queen who doesn’t think it’s appropriate to have other Drag Queens visit schools and libraries to read to pre-teen kids:

Drag Queen Kitty Demure has taken to Twitter to speak out against the sexualization of children by woke people co-opting drag culture and rebranding it as an educational tool.

“I have absolutely no idea why you would want [drag queens] to influence your child. Would you want a stripper or porn star to influence your child?”

A friendly message to mothers who want their kids influenced by drag. #dragqueensarenotforkids #dragqueenstorybookhour #drag #moms #woke #Liberals pic.twitter.com/EmOovz4E3F

— Kitty Demure (@demure_kitty) January 19, 2020

Demure notes that just as you wouldn’t take your kids out to see porn stars or strippers read stories while in full dress and makeup, you shouldn’t take them to see drag. There’s an effort to introduce kids earlier and earlier to adult sexuality. The idea is that this will help kids be more open-minded and understanding about the difference. What it really does is normalize deviant adult behaviour in children’s minds and override their own instincts. Giving children access to sexual content makes them think this kind of thing is for them, it opens doors that should stay closed until a child is of age.

Demure says here what all of us know: drag culture is adult entertainment. The look is sexualized. The names are sexualized. In fact, the entire concept of drag is a send-up of beauty queen culture. Beauty queen culture is sexualized as well, and while that is sometimes subsumed beneath the surface, it’s obviously fully part of it. That’s what drag plays on. Drag can be lots of fun, but it’s grown-up fun, not for kids.