… But we can approach this the other way too, looking at capitalism rather than engineering. As Adam Smith didn’t quite say (but as I do, often) capitalists are lazy, stupid and greedy. Finding that new way to make money is really difficult. So, very few try. Once someone does try and find then all the lazy — and greedy, did I mention that? — capitalist bastards copy what is being done. This hauls vast amounts of capital into that area, competition erodes the profits being made by the pioneer and the end result is that it’s consumers who make out like bandits. The result (here) is that the entrepreneur makes 3% or so of the money and the consumers near all the rest. This is the very thing that makes this capitalist and free market thing work.

Tim Worstall, “Folks Are Copying SpaceX – That’s How Capitalism Works”, It’s all obvious or trivial except …, 2024-09-16.

December 17, 2024

QotD: Capitalism is a combination of laziness, stupidity, and greed

September 17, 2024

Unbearable anti-humanism

Tim Worstall responds to a recent dispatch-from-dystopia from Christopher Ketcham, decrying the “Unbearable Anthropocentrism” he sees in the world:

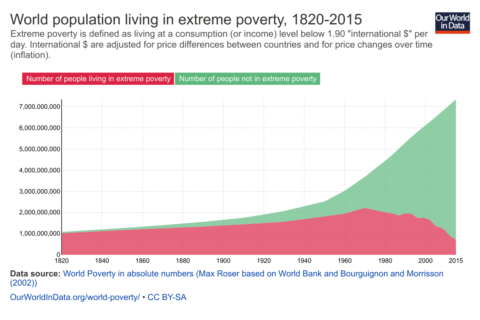

No idea who Ketcham is built then he doesn’t know who I am so we’re equal there. His complaint is that Our World in Data tends to show that the world is becoming a better place. Poverty is decreasing, infant mortality rates are falling, more folk have at least a square and ever increasing numbers are getting three and so on.

This is, as the cool kids say, problematic. Because if the thing to be opposed — capitalism and markets — is making the world a better place then where will we get the revolutionary fortitude to get rid of what is making the world a better place?

Something must be wrong here, right? Well, yes, it is:

For obvious reasons, Roser’s cheerful view of capitalist business-as-usual – and the data that would seem to support it – has made him a darling of libertarian market fundamentalists, who have lavished praise on his work.

See, this is problematic. So, what?

Given the support that Roser enjoys from billionaire oligarchs at the pinnacle of the capitalist system, one wonders if it is a coincidence that so much of the data he headlines for public consumption happens to valorize that system.

Oooooh, no, the claim isn’t that he’s writing lies. It’s just a question that is being asked. Could it, you know, I wonder if …

To which the correct answer is that Ketcham is a tosser. For it really is true that these last 40 years of global neoliberalism have coincided — at the very least coincided with — the greatest reduction in abject poverty in the entire history of our species.

But because capitalism, markets, the ghastly little tosser has to spread shade on someone reporting — honestly reporting — this truth. Hey, sure, we can have lots of lovely arguments about causation and so on. But reporting facts is wrong if they’re politically inconvenient? Someone will only report facts if they’re being paid — bribed — to do so?

Fuck off laddie, go die in a ditch.

Like, you know, far too many of us all did before this capitalism, markets, shit.

Fuck off.

June 21, 2024

“Neoliberal ideology is antidemocratic at its very core. Its aim is to give free-reign over our societies to corporations, not citizens”

Tim Worstall responds to a recent Medium essay by Julia Steinberger which illustrates that “neoliberal” has joined “fascist” as a generic term to indicate strong disapproval of a person, organization, or idea:

The idea that an adult woman can believe these things is just amazeballs. But here we are. A tweet from Julia Steinberger leads to her Medium essay about what’s wrong with the world.

An upheaval in 10 chapters:

1. The cause. We know the climate crisis is brought to us by highly unequal and undemocratic economic systems.

Err, no? Emissions are emissions. 100 people emitting one tonne each is exactly the same as 1 person emitting 100 tonnes. Sure, it’s true that a more unequal society will have more people emitting those 100 tonne personal amounts. But a more equal society will have more people able to emit another 1 tonne each. For, more equality is by definition the movement of some of those assets of the richer to those poorer — the economic assets which either allow or do the emitting. Sure, Jim Ratcliffe’s £50,000 private jet flight emits more than my £100 Easyjet one. But if we take the £50k off Jim and give it to 500 folk like me then all 500 of us might spend the marginal income on an Easyjet flight each — which would be more emissions than Jim’s spending of the money.

It simply is not true that economic inequality is the heart, the core or the cause of climate change. It’s idiocy to think it is too.

Of course, we know what’s happening here. Climate Change is Bad, M’Kay? Which it is, obviously. Economic inequality is Bad, M’Kay? Well, there the evidence is a great deal more mixed but whatever. But in the minds of the stupid all bad things have the same cause. So, if inequality is bad, climate change is bad, then they must be the same thing because they’re Bad, M’Kay?

2. The rise. The recent history of these economic systems, in the Americas and Eurasia, is dominated by the ascendance of neoliberal ideology.

Oh, that is good. Given that I am a neoliberal — a fully paid up one, Senior Fellow at the Adam Smith Institute and all — that’s very good. Given HS2, looming wealth taxation, the increased bite of idiot regulation and all that I can’t say that I see neoliberalism as winning right now but that might depend upon your starting point. If you’re a socialist — or an idiot but I repeat myself — you might well regard the plenitude of bananas in the supermarket as neoliberal. After all, that is something that socialism never did achieve.

3. The threat. Neoliberal ideology is antidemocratic at its very core. Its aim is to give free-reign over our societies to corporations, not citizens.

And, well, you know, bollocks. The very beating heart of neoliberalism is that corporations need to be controlled and they’re best controlled by the citizens. In the form of free markets rather than voting on which bureaucrats get the gold plated pension, true. But neoliberals are between indifferent and actually against capitalist power. The whole nub of the idea is that markets do the job of controlling capitalists better than bureaucrats, politicians or, obviously, capitalists.

There’s not really any way for her thesis to survive after getting so much of the basics wrong, is there?

But just one more tidbit:

Hayek and his neoliberal colleagues now needed another, antidemocratic way, to organise society. They didn’t want democracy, but they wanted some kind of self-maintaining organisation — by which they meant hierarchy. Organisation was supposed to be supplied by the market, and hierarchy by competition within markets. (It’s worth noting that neoliberals in the 1950s did not, although they should have, predict that unfettered markets lead to concentrations in monopolies or cartels. They would arguably disapprove of the vast corporations running our current economies, even though their market-above-democracy policies predictably brought them into being.)

Well, that wasn’t actually the last tidbit. But the idea that Friedman, Mises, Menger, Hayek and the rest didn’t worry about monopolies? Jesu C is really bouncin’ on that pogo stick right now. And then the idea that democracy will be better bulwark against monopolies than markets? Can you actually do backflips on a pogo stick?

June 4, 2024

QotD: “Let the market handle it”

The argument is quite common. It’s also wrong. Its error is that it incorrectly identifies the set of choices for dealing with problems (and with “problems”).

Rodrik’s argument appears to be the height of reasonableness. “It is dogmatic and dangerous,” the argument’s champions rightly note, “to assume that one solution or one approach is the answer to every problem. Some problems call for the use of screwdrivers, others call for the use of hammers. Only a benighted fool insists on using a screwdriver to hammer in nails and on using a hammer to insert screws. The wise, non-ideological, enlightened, open-minded, reasonable, and scientifically aware person sometimes uses a screwdriver and other times uses a hammer. What could be more reasonable?!”

The error in this formulation is that markets are many tools. Markets are a toolkit with far more tools in it than government has access to. While government has only a few tools – mostly hammers (some sledge), saws, and clamps – the market is filled with many, almost countless, tools. And the market’s tools are much more varied, nuanced, specialized, and creative than are the government’s simple set of tools.

Put differently, to say “Let the market handle it” is just a shorthand way of saying “Let whoever is most willing, most able, most experienced, most knowledgeable, and best equipped be free to try his or her hand at dealing with each specific problem.” And to say “Let the market always handle it” is not – contrary to what Rodrik’s argument suggests – to propose a single, simple fix for all problems; it is to propose that the field be left open for as many fixes as are feasible to be tried. To say “Let the market always handle it” is to warn that using government as a fix crowds out – prevents – experimentation with many other possible fixes.

In short, the choice is not between only two alternative possible fixes: the market or the government. Instead, the choice is between a gigantically large and varied set of possible fixes (the market, with its many detailed specialized carpenters and master builders) or a tiny set featuring one possible fix (the government, with its hammering, sawing, and clamping officials, none of whom – unlike the case with market participants – can be reasonably presumed to know enough of the finer details of any of the problems that they are called upon to “fix”).

The truly reasonable person – the one who understands the benefits of having access to as many “solutions” to problems as possible – supports the market because he or she knows that to turn to government solutions is to drastically reduce the number of “solutions” that will be tried.

Don Boudreaux, “Very Bad Framing, or In Defense of ‘Let the Market Handle It'”, Café Hayek, 2016-08-12.

November 23, 2023

QotD: The Austrian and Chicago schools of economics

[Bureaucracies will always expand far beyond the “problem” they were instituted to address] was, anyway, the view of that “Austrian school economist”, Ludwig von Mises, proponent like the rest in that school of “classical liberalism”. His hatred of bureaucracy was a wonderful, animated thing. In his great book, Human Action, and many others, he could become almost boring on the topic. What distinguishes the Austrian school from, say, the famous Chicago school of Milton Friedman and his ilk, was its European origin. (They were, however, consciously allied.) The “Austrians” go back, to Catholic antecedents, and their interests are not reducible to “pure economics” (scare quotes because there is no such thing). Over time it extended to broad social questions, and through a constant interest in the history of ideas. These were multilingual and multicultural, in the manner of the old Habsburg empire; where our American classical liberalism has been almost unilingually English, provincially distrustful of foreign thinkers, and buzzing with statistics. (You’ll need a degree in math.)

War propelled the “Austrian” thinkers westward, and the fall of the Berlin wall propelled the “Chicago” school east. The terms no longer have geographical significance.

What all classical liberals have in common is the passionate vindication and defence of human freedom. That is what makes them, unlike progressives, readable in subsequent generations. Their subject matter cannot become dated. The “Austrians” are also necessary to understand modern history, positively as well as negatively, in the evolution of, for instance, the Christian Democratic movement that conceived a peaceful post-war Europe, in defiance of secularizing bureaucratic trends and mass-man “ideals”. Alas, this was overall defeated by the Eurocratic trend-setters, determined to build a magnificent autocratic monument to themselves.

I have the most enchanting memory of opening the box that contained an American reprint of Human Action (big thick book), which I had ordered at the age of fifteen. I no longer own a copy, but gather it still stands as a monument to the resistance — a study of “praxeology”, or purposeful human choices, stretching so wide that even religion and morality could be touched. (Conventional economics has no time for either.) A half-century later, I can even remember the construction of an earnest reading list, that was soon abandoned when I went on the road.

One may see the great division in Western thought and politics, which the Austrian-school Friedrich Hayek traced back to Bacon and Descartes, and can be traced farther to the Nominalists of the later Middle Ages. Humans live in freedom and make choices, to be restrained only by the plainest moral codes. Or, by the alternative thesis, we are components of a machine, which the man with Power can monkey with, by implanting stimuli here and there.

We are creatures of God, or — we are replaceable parts in a bureaucracy.

David Warren, “Austrian schoolboy”, Essays in Idleness, 2019-09-17.

November 4, 2023

October 5, 2021

QotD: Entrepreneurship

If entrepreneurs see value in the […] economic landscape, and perceive there are rich profits to be made in turning around businesses and then flogging them off, it is very good news indeed for the country’s economy. By releasing capital from uneconomic areas and focussing it on lucrative new bits, the overall pie gets bigger, jobs get created, and productivity is also increased.

In fact, one could almost create a new economic law: the amount of abuse raining down on entrepreneurs is directly proportional to the good they do. I haven’t seen much reason to doubt this law yet.

Johnathan Pearce, “Gordon Gekko goes to Germany”, Samizdata.net, 2005-05-05.

November 27, 2019

QotD: The evolution of markets

It is a settled assumption among most libertarians, classical liberals and English-speaking conservatives that market behaviour is part of human nature. Whether or not we care to make a point of it, we stand with John Locke and, through him, with the men of the Middle Ages and with the Greeks and Romans, in trying to derive what is right from what is natural.

We believe that there is a natural inclination to promote our own welfare and that of our loved ones. We further believe that, given reasonable security of life and property, this inclination will lead to the emergence of a system of voluntary exchange. That is, we will seek to trade the things we have or can create for other things that we regard as of greater value to ourselves.

In doing so, ratios of exchange that we call prices will be revealed. These prices, in turn, will provide general information about what should be produced, in what ways and in what quantities. Furthermore, changes in price will provide information about changes in preferences or in abilities to produce. Custom will set aside one or more goods to serve as money. Institutions will emerge that channel savings into productive investment, that spread risk, and that moderate expected fluctuations in price. Laws will develop to police the transfer of property and performance of contracts.

We believe that market economies emerge spontaneously and are self-regulating and self-sustaining. This is not to say that all market societies will be the same. Their exact shape will depend on the intellectual and moral qualities of the individuals who comprise them. They will reflect pre-existing patterns of trust and honesty and the general cultural and religious values of a people. They will also be more or less distorted by government intervention. But we do say that market behaviour is natural — that, in the absence of extreme government coercion, or extreme disorder, buying and selling to increase our own welfare is what we naturally do.

Sean Gabb, “Market Behaviour in the Ancient World: An Overview of the Debate”, 2008-05.

November 23, 2019

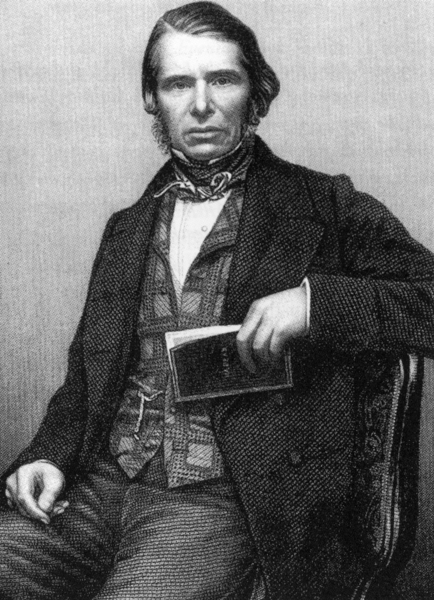

Sir Charles Trevelyan, head of the Irish relief efforts during the potato famine, and creator of the modern civil service

By happenstance, after posting the OSP video on the history of Ireland, a post at Samizdata covered one of the questions I had from OSP’s summary, specifically that the famine was worsened by British “laissez-faire mercantilism”. Mercantilism is rather different from any kind of laissez-faire system, so it was puzzling to hear Blue link them together as though they were the same thing. Of course, I live in a province currently governed by the Progressive Conservative party, so it’s not like I’m unable to process oxymorons as they go by…

Anyway, this post by Paul Marks looks at the man in charge of the relief efforts:

Part of the story of Sir Charles Trevelyan is fairly well known and accurately told. Charles Trevelyan was head of the relief efforts in Ireland under Russell’s government in the late 1840s – on his watch about a million Irish people died and millions more fled the country. But rather than being punished, or even dismissed in disgrace, Trevelyan was granted honours, made a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (KCB) and later made a Baronet, not bad for the son of the Cornishman clergyman. He went on to the create the modern British Civil Service – which dominates modern life in in the United Kingdom.

Charles Edward Trevelyan (contemporary lithograph). This appeared in one of the volumes of “The drawing-room portrait gallery of eminent personages principally from photographs by Mayall, many in Her Majesty’s private collection, and from the studios of the most celebrated photographers in the Kingdom / engraved on steel, under the direction of D.J. Pound; with memoirs by the most able authors”. Many libraries own copies.

Public domain, via Wikimedia.With Sir Edwin Chadwick (the early 19th century follower of Jeremy Bentham who wrote many reports on local and national problems in Britain – with the recommended solution always being more local or central government officials, spending and regulations), Sir Charles Trevelyan could well be described as one of the key creators of modern government. If, for example, one wonders why General Douglas Haig was not dismissed in disgrace after July 1st 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme when twenty thousand British soldiers were killed and thirty thousand wounded for no real gain (the only officers being sent home in disgrace being those officers who had saved some of them men by ordering them stop attacking – against the orders of General Haig), then the case of Sir Charles Trevelyan is key – the results of his decisions were awful, but his paperwork was always perfect (as was the paperwork of Haig and his staff). The United Kingdom had ceased to be a society that always judged someone on their success or failure in their task – it had become, at least partly, a bureaucratic society where people were judged on their words and their paperwork. A General, in order to be great, did not need to win battles or capture important cities – what they needed to do was write official reports in the correct administrative manner, and a famine relief administrator did not have to actually save the population he was in charge of saving – what he had to do was follow (and, in the case of Sir Charles, actually invent) the correct administrative procedures.

But here is where the story gets strange – every source I have ever seen in my life, has described Sir Charles Trevelyan as a supporter of “Laissez Faire” (French for, basically, “leave alone”) “non-interventionist” “minimal government” and his policies are described in like manner. […]

Which probably explains why Blue used the term in the previous video. Then these “laissez-faire” policies are summarized, which leads to this:

None of the above is anything to do with “laissez faire” it is, basically, the opposite. Reality is being inverted by the claim that a laissez faire policy was followed in Ireland. A possible counter argument to all this would go as follows – “Sir Charles Trevelyan was a supporter of laissez faire – he did not follow laissez faire in the case of Ireland, but because he was so famous for rolling back the state elsewhere (whilst spawning the modern Civil Service) – it was assumed that he must have done so in the case of Ireland“, but does even that argument stand up? I do not believe it does. Certainly Sir Charles Trevelyan could talk in a pro free market way (just as General Haig could talk about military tactics – and sound every inch the “educated soldier”), but what did he actually do when he was NOT in Ireland?

I cannot think of any aspect of government in the bigger island of the then UK (Britain) that Sir Charles Trevelyan rolled back. And in India (no surprise – the man was part of “the Raj”) he is most associated with government road building (although at least the roads went to actual places in India – they were not “from nowhere to nowhere”) and other government “infrastructure”, and also with the spread of government schools in India. Trevelyan was passionately devoted to the spread of government schools in India – this may be a noble aim, but it is not exactly a roll-back-the-state aim. Still less a “radical”, “fanatical” devotion to “laissez faire“.

August 10, 2019

QotD: Progressives and spontaneous order

I suspect that the single biggest factor that distinguishes “Progressives” from libertarians and free-market conservatives is the simple fact that “Progressives” do not begin to grasp the reality of spontaneous order. “Progressives” seem unable to appreciate the reality that productive and complex economic and social orders not only can, but do, emerge unplanned from the countless local decisions of individuals each pursuing his or her own individual plans. Therefore, “Progressives” naturally adopt a creationist view of society and of the economy: without a conscious and visible (and well-intentioned) guiding hand, society and the economy cannot possibly work very well. Indeed, it seems that for many (most?) “Progressives,” the idea that a spontaneously ordered economy can work better than one directed consciously from above – or, indeed, that a spontaneously ordered economy can work at all – is so absurd that when “Progressives” encounter people who oppose “Progressive” schemes for regulating the economy, “Progressives” instantly and with great confidence conclude that their opponents are either stupid or, more often, evil cronies for the rich and the powerful.

Conduct an on-going experiment: whenever well-meaning “Progressives” (of which there are very many) propose this government intervention or oppose that policy of reducing government’s role in the economy, ask if these “Progressives'” stated reasons can be understood to be nothing more than a reflection of a failure to understand the power and range of spontaneous-ordering forces in private-property settings. The answer will almost always be “yes.” Very often, no further explanation for “Progressives'” policy stances is necessary.

“Progressives” simply don’t “get” spontaneous order in human society. They see a problem and leap to the only conclusion that for them is sensible – namely, that that problem’s only realistic “solution” is that it be directly addressed by government officials. Indeed, even “Progressives'” frequent misdiagnoses of the results of trade-offs as being “problems” (or “market failures”) reflect a failure to understand spontaneous-ordering processes. Many phenomena and patterns that “Progressives” assume to be problems – for example, increasing inequality of monetary incomes – are often the benign results of the countless and nuanced individual trade-offs made by individuals. For “Progressives,” though, these “outcomes” are often assumed to be the consequence of sinister designs.

Don Boudreaux, “Bonus Quotation of the Day…”, Café Hayek, 2017-06-24.

July 8, 2019

May 25, 2019

February 26, 2019

Laissez-faire versus “Fairtrade”

In the Guardian, a sad tale of the fading bright hopes of the (relatively small number of) affluent westerners who passionately supported the “Fairtrade” movement:

When, in 2017, Sainsbury’s announced that it was planning to develop its own “fairly traded” mark, more than 100,000 people signed a petition condemning the move. Today, on the eve of Fairtrade Fortnight, the fact that most supermarkets have moved away from the standards developed by the Fairtrade Foundation is worrying.

While some grocery chains have sought the foundation’s stamp of approval, many have gone their own way. This means most consumers have little sense of which organisation is doing what to protect the wages and rights of developing world workers. Over the next two weeks, the foundation plans to focus its publicity efforts on cocoa farmers in west Africa and the way the Fairtrade mark can improve their lives.[…]

That is a sad situation. After the great financial crash of 2008, a commodity boom that lasted from 2013 to 2017 turned into a slump that has robbed farmers and developing world governments of vital cash. Just as they were managing to stabilise their finances and set aside money to invest, the world price tumbled and wiped out their profit. Fairtrade practices protect farmers from this sort of setback and allow them to plan for the future.

Of course they have their critics. These are most mostly from the US – people who favour unfettered markets and seek to undermine the Fairtrade ideal, saying it is a form of protectionism that dampens innovation and ultimately ruins farms.

Theirs is an almost religious adherence to the free market that discounts the gains in stability and security that Fairtrade provides, and the scope of the community premium to promote universal education and the rights of women.

But without large employers making strides to adopt the standardised and transparent Fairtrade practices put forward by the foundation, it will be left to consumers to drive the project forward.

At the Continental Telegraph, Tim Worstall responds:

The Guardian tells us that the Great White Hope of global trade, Fairtrade, isn’t in fact working. On the basis that no one seems to be doing very much of it. To which the answer is great – for the only fair trade is laissez faire.

This does not mean that Fairtrade should not have been tried – to insist upon that would be to breach our basic insistence upon the value of peeps just getting on with doing what they want, laissez faire itself. But the very value of that last is that we go try things out, see whether they work and if they don’t we stop doing them. If they do then great, we do more of them.

[…]

So, trying out Fairtrade, why not? Let’s go see how many other people feel the same way? In exactly the same way we find out whether people like Pet Rocks, skunk or Simon Cowell. Product gets put on the market we see whether it adds to human welfare or not. If people value it – and revealed preferences please, by actually buying it – at more than the use of those scarce resources in other uses then that’s adding to human welfare and long may it thrive. If it doesn’t, if it’s subtracting value from the human experience, then we’ll stop doing it as those trying go bust.

This is not an aberration of the system it is the system and it’s why laissez faire works. Peeps get to do whatever and we keep doing more of what works, less of what doesn’t.

Fairtrade? No, I never thought it was going to work as anything other than virtue signalling for Tarquin and Jocasta but that’s fine. Why shouldn’t Tarquin and Jocasta gain their jollies by virtue signalling? As it turns out, now that we’ve tried it, no one else gives a faeces*. So, we can stop. Except, obviously enough, for those specialist outlets like the Co Op where the odd can still gain their jollies. It being that very mark of a laissez faire, liberal, society that the jollies of the odd are still catered to in due proportion to the desire for them.

*From Gibbon, all the fun stuff’s in Latin.

October 1, 2017

Deirdre McCloskey on the rise of economic liberty

Samizdata‘s Johnathan Pearce linked to this Deirdre McCloskey article I hadn’t seen yet:

Since the rise during the late 1800s of socialism, New Liberalism, and Progressivism it has been conventional to scorn economic liberty as vulgar and optional — something only fat cats care about. But the original liberalism during the 1700s of Voltaire, Adam Smith, Tom Paine, and Mary Wollstonecraft recommended an economic liberty for rich and poor understood as not messing with other peoples’ stuff.

Indeed, economic liberty is the liberty about which most ordinary people care.

Adam Smith spoke of “the liberal plan of [social] equality, [economic] liberty, and [legal] justice.” It was a good idea, new in 1776. And in the next two centuries, the liberal idea proved to be astonishingly productive of good and rich people, formerly desperate and poor. Let’s not lose it.

Well into the 1800s most thinking people, such as Henry David Thoreau, were economic liberals. Thoreau around 1840 invented procedures for his father’s little factory making pencils, which elevated Thoreau and Son for a decade or so to the leading maker of pencils in America. He was a businessman as much as an environmentalist and civil disobeyer. When imports of high-quality pencils finally overtook the head start, Thoreau and Son graciously gave way, turning instead to making graphite for the printing of engravings.

That’s the economic liberal deal. You get to offer in the first act a betterment to customers, but you don’t get to arrange for protection later from competitors. After making your bundle in the first act, you suffer from competition in the second. Too bad.

In On Liberty (1859) the economist and philosopher John Stuart Mill declared that “society admits no right, either legal or moral, in the disappointed competitors to immunity from this kind of suffering; and feels called on to interfere only when means of success have been employed which it is contrary to the general interest to permit — namely, fraud or treachery, and force.” No protectionism. No economic nationalism. The customers, prominent among them the poor, are enabled in the first through third acts to buy better and cheaper pencils.

[…]

Indeed, economic liberty is the liberty about which most ordinary people care. True, liberty of speech, the press, assembly, petitioning the government, and voting for a new government are in the long run essential protections for all liberty, including the economic right to buy and sell. But the lofty liberties are cherished mainly by an educated minority. Most people — in the long run foolishly, true — don’t give a fig about liberty of speech, so long as they can open a shop when they want and drive to a job paying decent wages. A majority of Turks voted in favour of the rapid slide of Turkey after 2013 into neo-fascism under Erdoğan. Mussolini and Hitler won elections and were popular, while vigorously abridging liberties. Even a few communist governments have been elected — witness Venezuela under Chavez.

September 19, 2017

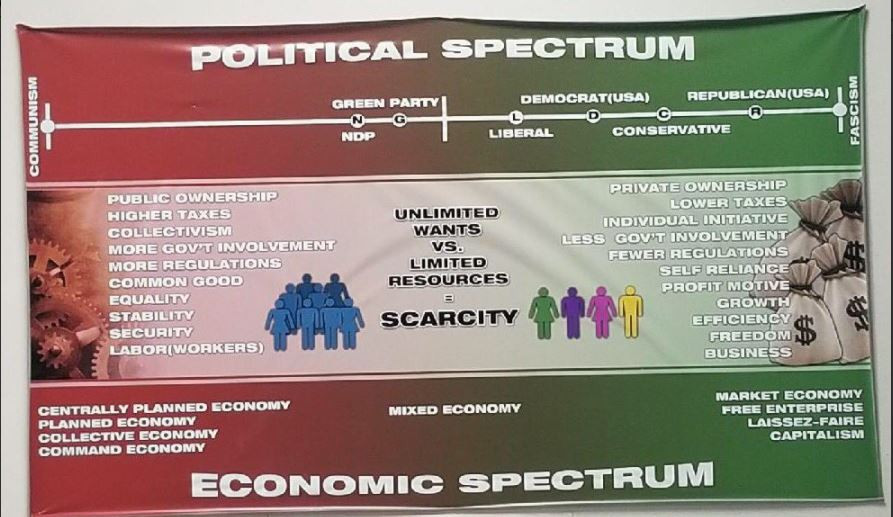

Even in a progressive educational bubble, this isn’t correct

Holly Nicholas shared this photo, which is said to be from an Alberta school:

If this is indeed how public schools are presenting the political spectrum (and it’s unfortunately easy to believe that they do), the closest thing to a “centrist” party in Canada is the loony left Green Party … who somehow pip the NDP on the right. The far right end of the spectrum, Fascism, is graphically indicated to be all about “Market Economy, Free Enterprise, and Laissez-Faire Capitalism”, because as we all remember, Hitler and Mussolini were in no way fans of state intervention in the economy, right?

The graphic does, however, support certain shibboleths of the left including implying that libertarians (who are actually in favour of market economies, free enterprise, and laissez-faire capitalism) are in the same economic and political basket as actual fascists. Nice work, faceless agitprop graphic artist!