The Cynical Historian

Published 1 Nov 2018Today let’s talk about Marxist historians. Edward Palmer Thompson makes perhaps the best introduction to the realm of Marxist history. His work on the English Labor Class, allows for a better understanding of the Marxist project, and how understanding class consciousness can lead to revolution.

————————————————————

references:

Beard, Charles. “Written History as an act of Faith”, The American Historical Review 39, no. 2 (January 1934), 219-231.Marx, Karl. The Essential Marx. ed. Leon Trotsky, abridgment of Das Kapital, Vol. I. 1939; Mineola, N.York: Dover Publications, 2006. https://amzn.to/2MWygco

Thompson, E.P. “The Moral Economy of the English Crowd in the Eighteenth Century”, Past and Present, No. 50 (Feb., 1971), 76-136.

Thompson, E.P. The Making of the English Working Class. New York: Pantheon Books, 1963. https://amzn.to/2KFSESC

Special thanks to Dr. Colleen Hall-Patton for proofreading the script for this episode.

————————————————————

Support the channel through Patreon:

https://www.patreon.com/CynicalHistorian

or pick up some merchandise at SpreadShirt:

https://shop.spreadshirt.com/cynicalh…LET’S CONNECT:

https://discord.gg/Ukthk4U

https://twitter.com/Cynical_History

————————————————————

Wiki:

Edward Palmer Thompson (3 February 1924 – 28 August 1993), usually cited as E. P. Thompson, was a British historian, writer, socialist and peace campaigner. He is probably best known today for his historical work on the British radical movements in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, in particular The Making of the English Working Class (1963). He also published influential biographies of William Morris (1955) and (posthumously) William Blake (1993) and was a prolific journalist and essayist. He also published the novel The Sykaos Papers and a collection of poetry. His work is considered to have been among the most important contributions to labour history and social history in the latter twentieth-century, with a global impact, including on scholarship in Asia and Africa.Thompson was one of the principal intellectuals of the Communist Party in Great Britain. Although he left the party in 1956 over the Soviet invasion of Hungary, he nevertheless remained a “historian in the Marxist tradition”, calling for a rebellion against Stalinism as a prerequisite for the restoration of communists’ “confidence in our own revolutionary perspectives”. Thompson played a key role in the first New Left in Britain in the late 1950s. He was a vociferous left-wing socialist critic of the Labour governments of 1964–70 and 1974–79, and an early and constant supporter of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, becoming during the 1980s the leading intellectual light of the movement against nuclear weapons in Europe.

————————————————————

Hashtags: #History #Marx #EPThompson #ClassConsiousness #Materialism #TheMakingOfTheEnglishWorkingClass

August 1, 2020

June 13, 2020

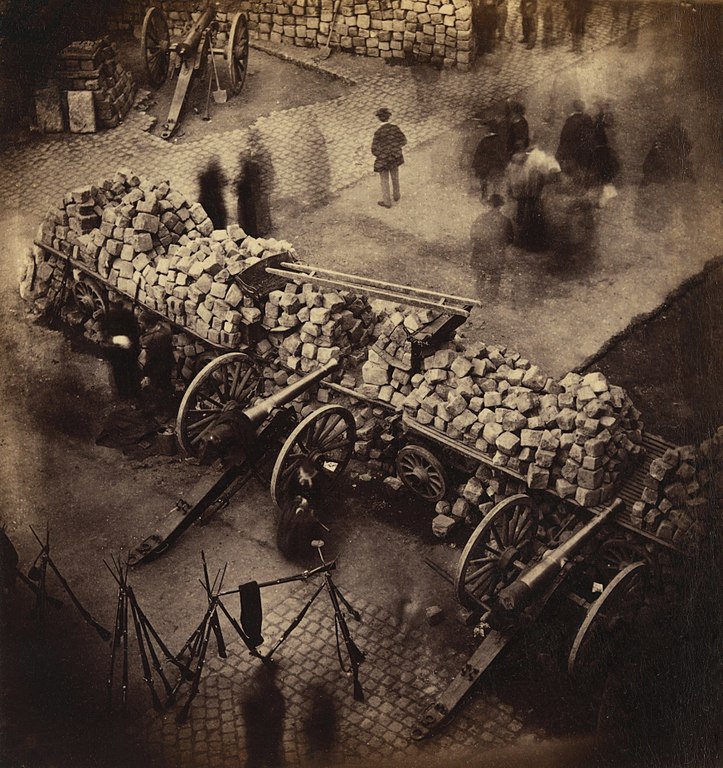

The CHAZ is a little bit 1968, a little bit 1789, but perhaps more 1871

Lawrence W. Reed finds the developments in the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone of Seattle remind him of the Paris Commune:

“‘Autonomous zone’ has armed guards, local businesses being threatened with extortion.”

That was quite a striking headline to behold. My immediate reaction was, “Oh my gosh, the Paris Commune is back!”

Except that it wasn’t Paris, and it wasn’t 1871. It was Seattle, Washington, USA — today. According to multiple reports, radical protesters seized a six-block area of the city. They declared it a police-free fiefdom, posted armed guards at its perimeter, began extorting money from local businesses (normally called “taxation”) and were even requiring residents to provide ID to enter their own homes.

The Paris Commune that lasted just 70 days in the spring of 1871 was born amid the ruins of France’s wartime loss at the hands of Prussia in the fall of the previous year. When the Prussians captured France’s Emperor Napoleon III, the monarchy collapsed, and the French Third Republic was born. In Versailles, just a few miles from Paris, its leaders sat on their hands as Parisians stewed in the toxic juices of defeat, resentment, and a rising tide of Marxist-inspired class warfare. The voices of the big mouths increasingly drowned out those of the more moderate citizens who preferred to get the city back to normal and work for a living.

On March 18, 1871, the socialist radicals seized the upper hand in the City of Lights. They occupied government buildings and ousted or jailed their opposition. It was a “People’s Revolution” (unless you were one of the people who didn’t support it). Karl Marx’s communist scribblings provided the radicals — called “Communards” — with their primary inspiration, but Marx himself later criticized their failure to immediately seize the Bank of France and march on the government in Versailles. In the early days of the Paris Commune, however, he hoped he was witnessing a fulfillment of his own delusions:

The struggle of the working class against the capitalist class and its state has entered upon a new phase with the struggle in Paris. Whatever the immediate results may be, a new point of departure of world-historic importance has been gained.

February 28, 2020

The Robin Hood complex – Social banditry theory and myth making

The Cynical Historian

Published 15 Dec 2016There’s one historical theory that people keep deluding themselves with, and it’s about time I pointed it out. Social banditry, or the “Robin Hood theory” is problematic at best and cultural misanthropy at worst.

Social bandit or social crime is a term invented by the Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm in his 1959 book Primitive Rebels, a study of popular forms of resistance that also incorporate behavior characterized by law as illegal. He further expanded the field in the 1969 study Bandits. Social banditry is a widespread phenomenon that has occurred in many societies throughout recorded history, and forms of social banditry still exist, as evidenced by piracy and organized crime syndicates. Later social scientists have also discussed the term’s applicability to more modern forms of crime, like street gangs and the economy associated with the trade in illegal drugs.

————————————————————

References:

Boessenecker, John. “California Bandidos.” Southern California Quarterly 80, i4 (Dec. 1, 1998), 419-434.Hall-Patton, Joseph. Pacifying Paradise: Violence and Vigilantism in San Luis Obispo. San Luis Obispo: California Polytechnic – San Luis Obispo thesis, 2016. http://www.digitalcommons.calpoly.edu…

Hobsbawm, Eric. Primitive Rebels: Studies in Archaic Forms of Social Movement in the 19th and 20th Centuries. New York: WW Norton & Company, 1965. https://amzn.to/2L6TDY0

Hobsbawm, Eric. Bandits. Rev. ed. New York: The New Press, 2000. https://amzn.to/2L4RagK

Rediker, Marcus. Outlaws of the Atlantic: Sailor, Pirates, and Motley Crews in the Age of Sail. Boston, Mass.: Beacon Press, 2014. https://amzn.to/2OasYf4

Linebaugh, Peter and Marcus Rediker. The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic. Boston, Mass.: Beacon Press, 2000. https://amzn.to/2JKq8tN

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_…

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zorro

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pancho_…

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joaquin…

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salomon…

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_B…

————————————————————

Patreon:

https://www.patreon.com/CynicalHistorianLET’S CONNECT:

https://twitter.com/Cynical_History

—————————————–

Hashtags: #History #SocialBanditry #PrimitiveRebellion #RobinHood #BillyTheKid

September 29, 2019

Being a dictator is a stressful vocation

Gustav Jönsson reviews a new book by Professor Frank Dikötter on twentieth-century dictators:

One of the first things to emerge from Professor Frank Dikötter’s eagerly awaited new book How to Be a Dictator is that it is a stressful vocation: there are rivals to assassinate, dissidents to silence, kickbacks to collect, and revolutions to suppress. Quite hard work. Even the most preeminent ones usually meet ignominious ends. Mussolini: summarily shot and strung upside down over a cheering crowd. Hitler: suicide and incineration. Ceausescu: executed outside a toilet block. Or consider the fate of Ethiopia’s Haile Selassie: rumoured to have been murdered on orders of his successor Mengistu Haile Mariam, he was buried underneath the latter’s office desk. Not the most alluring career trajectory, one might say.

Dikötter’s monograph is a study of twentieth century personality cults. He examines eight such cults: those created by Mussolini, Hitler, Stalin, Mao, Kim Il-sung, Duvalier, Ceausescu, and Mengistu. For them, cultism was not mere narcissism, it was what sustained their regimes; foregoing cultism, Dikötter argues, caused swift collapse. Consider Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge. Cambodians were unsure of Pol Pot’s exact identity for years, even after he had assumed leadership of the country. The Khmer Rouge, meanwhile, was in its initial stages merely called “Angkar” — “The Organisation.” There was no inspiring iconography. There was no ritualised leader worship. There was only dark terror. Dikötter quotes historian Henri Locard: “Failing to induce adulation and submissiveness, the Angkar could only generate hatred.” The Khmer Rouge soon lost its grip on the country. Dikötter makes an obligatory reference: “Even Big Brother, in George Orwell’s 1984, had a face that stared out at people from every street corner.”

Readers of Orwell will remember that INGSOC has no state ideology. There is only what the Party says, which can change from hour to hour. Likewise, Dikötter argues, there was no ideological core to twentieth century dictatorships; there was only the whim of the dictator. Nazism, for example, was not a coherent creed. It contained antisemitism, nationalism, neo-paganism, etc., but its essence was captured in one of its slogans: The Führer is Always Right. That is what the creed amounted to. Indeed, the NSDAP referred to itself simply as “the Hitler movement.” Nazism was synonymous with Hitlerism. Italian Fascism was perhaps even more vacuous. The regime’s slogan was simple: Mussolini is Always Right. Explaining his method of politics, Mussolini said: “We do not believe in dogmatic programmes, in rigid schemes that should contain and defy the changing, uncertain, and complex reality.”

While it is uncontroversial to argue that Nazism and Fascism were without ideology, as Dikötter writes, the “issue is more complicated with communist regimes.” Naturally, Marxism was connected with Stalin, Mao, Ceausescu, Kim, and Mengistu. But Dikötter rightly says that it was Lenin’s revolutionary vanguard, not Marx’s philosophical works, that inspired them. Doctrines can be interpreted in contradictory ways, creating schismatic movements — as shown throughout the history of socialism. In this regard personality cults are far safer because they are substantively empty. Marxist dictators thus subverted Marxism. Engels had said that socialism in one country was impossible, but that is what Stalin’s Soviet Union favoured. Or consider Kim’s North Korea, which in 1972 replaced Marxism with Great Leader Thought. And as Dikötter writes, “Mao read Marx, but turned him on his head by making peasants rather than workers the spearhead of the revolution.” Reading Marx under Marxism, Dikötter says, was highly imprudent: “One was a Stalinist under Stalin, a Maoist under Mao, a Kimist under Kim.” In short, Marxism was whatever the dictator said, and not what Marx had actually written.

May 14, 2019

QotD: Karl Marx, noted racist

For those who see Marx as their hero, there are a few historical tidbits they might find interesting. Nathaniel Weyl, himself a former communist, dug them up for his 1979 book, Karl Marx: Racist. For example, Marx didn’t think much of Mexicans. When the United States annexed California after the Mexican War, Marx sarcastically asked, “Is it a misfortune that magnificent California was seized from the lazy Mexicans who did not know what to do with it?” Engels shared Marx’s contempt for Mexicans, explaining: “In America we have witnessed the conquest of Mexico and have rejoiced at it. It is to the interest of its own development that Mexico will be placed under the tutelage of the United States.”

Marx had a racial vision that might be interesting to his modern-day black supporters. In a letter to Engels, in reference to his socialist political competitor Ferdinand Lassalle, Marx wrote: “It is now completely clear to me that he, as is proved by his cranial formation and his hair, descends from the Negroes who had joined Moses’ exodus from Egypt, assuming that his mother or grandmother on the paternal side had not interbred with a nigger. Now this union of Judaism and Germanism with a basic Negro substance must produce a peculiar product. The obtrusiveness of the fellow is also nigger-like.” Engels shared Marx’s racial philosophy. In 1887, Paul Lafargue, who was Marx’s son-in-law, was a candidate for a council seat in a Paris district that contained a zoo. Engels claimed that Lafargue had “one-eighth or one-twelfth nigger blood.” In a letter to Lafargue’s wife, Engels wrote, “Being in his quality as a nigger, a degree nearer to the rest of the animal kingdom than the rest of us, he is undoubtedly the most appropriate representative of that district.”

Marx was also an anti-Semite, as seen in his essay titled “On the Jewish Question,” which was published in 1844. Marx asked: “What is the worldly religion of the Jew? Huckstering. What is his worldly God? Money. … Money is the jealous god of Israel, in face of which no other god may exist. Money degrades all the gods of man — and turns them into commodities. … The bill of exchange is the real god of the Jew. His god is only an illusory bill of exchange. … The chimerical nationality of the Jew is the nationality of the merchant, of the man of money in general.”

Walter E. Williams, “What Do Leftists Celebrate?”, Townhall.com, 2017-05-10.

December 30, 2018

QotD: The national honour

The Greek historian Thucydides argued that countries go to war for three reasons: honor, fear and interest. He put honor first, and yet that is probably the least appreciated aspect of foreign policy today. Historian Donald Kagan, in his essay “Honor, Interest, Nation-State,” recounts how since antiquity, nations have put honor ahead of interest. “For the last 2,500 years, at least, states have usually conducted their affairs and have often gone to war for reasons that would not pass the test of ‘vital national interests’ posed by modern students of politics.”

“On countless occasions,” he continues, “states have acted to defend or foster a collection of beliefs and feelings that ran counter to their practical interests and have placed their security at risk, persisting in their course even when the costs were high and the danger was evident.”

Americans instinctively understand this when our own honor is at stake. The rallying cry during the Barbary Wars, “Millions for defense, but not one cent for tribute,” has almost become part of the national creed. I am no fan of Karl Marx, but he was surely right when he observed that “shame is a kind of anger turned in on itself. And if a whole nation were to feel ashamed it would be like a lion recoiling in order to spring.”

Both the first and second world wars cannot be properly understood without taking the role national honor plays in foreign affairs. Similarly, Vladimir Putin’s constant testing of the West only makes sense when you take into account the despot’s core conviction that the fall of the Soviet Union was a blow to Russian prestige and honor.

Jonah Goldberg, “Humiliating Mexico Over Border Wall Would Be a Big Mistake”, TownHall.com, 2017-01-27.

December 6, 2018

“Marx was right”

An interesting little bit of history and philosophy over at Rotten Chestnuts:

Marx was right: Society really is shaped by relations between the means of production.

The Middle Ages, for instance, organized itself around defense from marauding barbarian hordes. Fast, heavy cavalry were the apex of military technology at the time; the so-called “feudal” system were the cavalry’s support. The system was field tested in the later Roman empire — medieval titles like “duke” came from the ranks of the Roman posse comitatus — and perfected in the Dark Ages.

When the barbarians had been pacified sufficiently that Europeans had leisure time to think about this stuff, they took the feudal system — at that point a cumbersome relic — as their model for society. Hobbes, Locke, et al saw it as the origin of the Social Contract; Marx saw it as finely tuned oppression. But here’s the fun part:

Hobbes ends his Leviathan with the most absolute monarch that could ever be. He starts* with… wait for it… the equality of man. Marx, on the other hand, ends with the equality of man. He starts with a frank, indeed brutal, acknowledgment of man’s inequality. As much as I love Hobbes (and consider Leviathan the only political philosophy book worth reading), he’s wrong — fundamentally wrong — and Marx is right. Marx went wrong somewhere down the line; Hobbes jumped the track from page one.

Marx only went wrong when he started dabbling in metaphysics. Marxism isn’t the original underpants gnome philosophy, but it’s certainly the best — not least because Marx’s followers were so successful at hiding the deus ex machina that was supposed to bring Communism about. Marx didn’t just say “The Revolution will happen because that’s the way all the trend lines are pointing.” He said “the trend lines are pointing that way, and oh yeah, the animating Spirit of History demands that the Revolution shall happen.” This is so obviously sub-Hegelian junk that his followers dropped it as fast as they could, but to Marx himself it was the key to his philosophy. For all its formidable technobabble, Marxism is just another chiliastic mystery cult.

[…] Enlightenment-wise, Hobbes was the start, Marx the end of political philosophy, and both are flawed beyond redemption. Hobbes sure sounds like a viable alternative to Marx, because Hobbes’s reasoning seems sound, and based on an irrefutable premise: That in the State of Nature, life is nasty, poor, solitary, brutish, and short. But that’s not Hobbes’s premise — the fundamental equality of man in the State of Nature is. Life in the State of Nature is brutal because all men are equal.

* If you’ve read Leviathan, of course, you know he starts the book itself with a long discourse on contemporary physics. Hobbes was an innovator there, too — he’s the first person to put forth his humanistic ideas as the coldly logical deductions of physical science. It’d be fun to taunt the “I fucking love science” crowd with that, except they think Hobbes is a cuddly cartoon tiger and “Leviathan” one of the lesser houses at Hogwarts.

September 22, 2018

QotD: Epicurean influences on Marx

… what’s also interesting is that our friends the Marxists also thought Epicurus was a great philosopher. Marx himself did his doctoral dissertation on the differences between the atomism of Epicurus and his forerunner Democritus.

Most books on Epicureanism published in France in the 20th century were written by Marxists. (Well, I suppose you could say that of most books published in France on any topics in the 20th century…!) I have a booklet on Lucretius at home published in France in the 1950s in a collection called Les classiques du peuple – The classics of the people. In the Acknowledgement section, the author thanks all the Soviet specialists of Epicureanism and materialism for any original insight that might appear in the book.

Marx found in Epicureanism a materialist conception of nature that rejected all teleology and all religious conceptions of natural and social existence.

Martin Masse, “The Epicurean roots of some classical liberal and Misesian concepts“, speaking at the Austrian Scholars Conference, Auburn Alabama, 2005-03-18.

July 23, 2018

QotD: The revolution of the proletariat wouldn’t play out the way Marx imagined

I remember a friend telling me that multi-culti was knocked out of his young skull when he got a job as a construction worker for the summer. Marxism too. He said if revolution came from the proletariat, the resulting society would view wife beating as a sort of little hobby, on the side, nothing bad, just a little indulgence on Saturday night. (Mind you this was not in the US. The US working class is by and large better than this.) And all those prejudices against other races/sexual orientations/etc? Yeah, the working class had no problems with those. Only a privileged twit like Marx could think that the working class all over the world wanted to unite. They tend to be rather more nationalistic than their “betters” after all. More all sorts of “ists” too (racist, sexist and homophobic[ist for completism]). It’s what works at their level, and virtue signaling buys them nothing.

Sarah Hoyt, “A Very Diverse Cake”, According to Hoyt, 2016-08-31.

July 8, 2018

QotD: Marx on how to run a true communist state

What really clinched this for me was the discussion of Marx’s (lack of) description of how to run a communist state. I’d always heard that Marx was long on condemnations of capitalism and short on blueprints for communism, and the couple of Marx’s works I read in college confirmed he really didn’t talk about that very much. It seemed like a pretty big gap.

[…]

I figured that Marx had just fallen into a similar trap. He’d probably made a few vague plans, like “Oh, decisions will be made by a committee of workers,” and “Property will be held in common and consensus democracy will choose who gets what,” and felt like the rest was just details. That’s the sort of error I could at least sympathize with, despite its horrendous consequences.

But in fact Marx was philosophically opposed, as a matter of principle, to any planning about the structure of communist governments or economies. He would come out and say “It is irresponsible to talk about how communist governments and economies will work.” He believed it was a scientific law, analogous to the laws of physics, that once capitalism was removed, a perfect communist government would form of its own accord. There might be some very light planning, a couple of discussions, but these would just be epiphenomena of the governing historical laws working themselves out. Just as, a dam having been removed, a river will eventually reach the sea somehow, so capitalism having been removed society will eventually reach a perfect state of freedom and cooperation.

Singer blames Hegel. Hegel viewed all human history as the World-Spirit trying to recognize and incarnate itself. As it overcomes its various confusions and false dichotomies, it advances into forms that more completely incarnate the World-Spirit and then moves onto the next problem. Finally, it ends with the World-Spirit completely incarnated – possibly in the form of early 19th century Prussia – and everything is great forever.

Marx famously exports Hegel’s mysticism into a materialistic version where the World-Spirit operates upon class relations rather than the interconnectedness of all things, and where you don’t come out and call it the World-Spirit – but he basically keeps the system intact. So once the World-Spirit resolves the dichotomy between Capitalist and Proletariat, then it can more completely incarnate itself and move on to the next problem. Except that this is the final problem (the proof of this is trivial and is left as exercise for the reader) so the World-Spirit becomes fully incarnate and everything is great forever. And you want to plan for how that should happen? Are you saying you know better than the World-Spirit, Comrade?

I am starting to think I was previously a little too charitable toward Marx. My objections were of the sort “You didn’t really consider the idea of welfare capitalism with a social safety net” or “communist society is very difficult to implement in principle,” whereas they should have looked more like “You are basically just telling us to destroy all of the institutions that sustain human civilization and trust that what is baaaasically a giant planet-sized ghost will make sure everything works out.”

Scott Alexander, “Book Review: Singer on Marx”, Slate Star Codex, 2014-09-13.

July 2, 2018

The holy book of Marx and the religion of progress

In the latest Libertarian Enterprise, Sarah Hoyt discusses the religious nature of progressive thought in the western world:

While the left not only filled every nook and cranny of twentieth century “narrative industries” to the point the only way a conservative could work in one of those was under deep, deep cover, the engineers made the internet.

The left didn’t even know it really had any serious opposition left. You can’t blame them too much. Even those of us who were very opposed and very disgusted kept it polite in public and treated them as retarded children who couldn’t take opposition.

Would it have made any difference if we’d talked back, say 30 years ago?

I doubt it.

You see, leftism is as much as anything else a religion. The crazy Marx with his vision of the future created an entire narrative from paradise (pre-capitalism, i.e. it never existed, guys, not even as apes. Apes, as we now know, trade) through fall into capitalism to eventual paradise again, where the New Man (what used to be called the Soviet Man) will be so altruistic and communally oriented that a government isn’t needed. (Like the peace of Islam, there’s only one way to obtain that, and no. Just no. Worldwide species extinction is as fantastical as the idea of that primordial paradise. Humans are humans, and someone will survive. I’m just not interested in letting them send us back ten thousand years.)

You hear it in the talk of the left — particularly the rather intellectually inbred fourth generation, who ate the pap the older people fed them and never had an original thought in their lives — stuff like calling us “reactionaries” (when they’re the ones in power, and have been for a long time, and the ones knee-jerk reacting) and talking about “the future” as belonging utterly to them, and the arrow of history, as though history were the chart in their book, with an arrow beneath.

Their faith doesn’t align particularly well with reality. For instance there’s the whole thing of them talking about us — always — as though we were the ones in power, when they have all the gatekeeping positions and all the contacts.

This dissonance has required them to make up invisible monsters that give us all the power: Patriarchy (a laughable idiocy in America and weak everywhere in the west. While they refuse to see it in the Middle East and Latin America where it actually exists in spades.) Micro aggressions. White privilege (which is so strong that it gives an edge to concentration camp survivors.)

All the while they refuse to admit the real privilege: Leftist privilege. The fastest way to rise in the narrative fields is to be lefter-than-thou. Because they’re in charge and that’s how the system is setup, so they can stay in charge.

Unfortunately this has created their isolation. You see, every song, every movie, ever history book, every fictional book, assures them they’ll win. They know that “the people united shall never be defeated.” They also know that though held back by patriarchy, racism, sexism and all the micro aggressions, the people really are with them. HAVE TO BE, because they’re ideology of the future, and history’s arrow points to their paradise. Every book, movie, etc. says so either subtly or openly. So they KNOW. Everybody knows.

March 21, 2018

Millennials and economics

In the Continental Telegraph, Tim Worstall views-with-alarm the economic illiteracy of many Millennials:

A most amusing piece over in Salon about how American millennials are certain that capitalism just ain’t gonna be around in the future therefore they see no point in saving for their retirements. Boy, ain’t they gonna get a surprise! One of the larger ones being that an absence of capitalism is going to, as it was before the emergence of the system, make having some savings for old age rather more important than it is now.

But there’s more there, of course there is, this is Salon we’re talking about:

The idea that we millennials’ only hope for retirement is the end of capitalism or the end of the world is actually quite common sentiment among the millennial left. Jokes about being unable to retire or anticipating utter social change by retirement age were ricocheting around the internet long before CNN’s article was published.

Well, that’s a generation shopping in the cat food aisle for their meat requirements in retirement then. But more:

Many millennials expressed to me their interest in creating self-sustaining communities as their only hope for survival in old age;

Certainly, that’s one way to do it. Move back to that pre-capitalist idea of the self-sustaining community which takes care of its oldsters. Be useful to have a name for those sorts of things but fortunately we’ve got one that already fits – families. Go and have those 6 to 8 kids and hope like hell that one stays home to change diapers. You did it for them after all.

I’m pretty sure that’s not how they’d see it if you presented it to them that way…

Dear Lord, has anyone even taught them some Marxism? For what’s being described there is the True Communism that will arrive once we’ve abolished economic scarcity. The thing which will come through the productive powers of bourgeois capitalism. You know, as Karl The Beard insisted? As, arguably, we have by any reasonable historical standard. A recent potter around Primark – yes, I know, not high up the list of fashionable outlets – showed that you could, or can, purchase an historically adequate set of clothing for a person for £100. Two day’s minimum wage labour. One set of clothes for everyday, one for Sunday Best. Including a warm coat and more changes of underwear than was usual back then.

No, seriously, there’s not been a period of human history when clothing – to give but one example – was as cheap as it is now. Not in relation to the effort needed to acquire it at least.

There’s actually a serious argument to be made that true communism has already arrived. Certainly Karl and Friedrich would be astonished at a society rich enough to be able to afford diversity advisers – if societal productive surplus is great enough to support that idea then surely communism has indeed arrived?

Boy, aren’t these millennials going to have a surprise when they grow up? That the Good Old Days are now?

November 17, 2017

QotD: Karl Marx and relativism

The most notable philosopher in this tradition was, of course, Karl Marx. He argued that the values of any civilisation — prior, at least, to the socialist culmination — are determined by its mode of production. He says:

In acquiring new productive forces men change their mode of production; and in changing their mode of production, in changing the way of earning their living, they change all their social relations. The hand-mill gives you society with the feudal lord; the steam-mill society with the industrial capitalist. The same men who establish their social relations in conformity with the material productivity, produce also principles, ideas, and categories, in conformity with their social relations. Thus the ideas, these categories, are as little eternal as the relations they express. They are historical and transitory products.

This is a radically subversive claim. It allows any institution, any custom, any set of beliefs — no matter how obviously right or true they might appear — to be dismissed as “ideology” or “false consciousness”. Let this claim be accepted, and our own claims about the naturalness of market behaviour falls to the ground.

With the remaining exception of North Korea and perhaps too of Cuba, the Marxist political experiments of the twentieth century have all long since collapsed, and, bearing in mind their known record of mass-murder and impoverishment, there are few who will admit to regretting their collapse. But Marxism as a critique of the existing order and as a theory of social change, remains alive and well in the universities. In its reformulation by Gramsci, as further developed by Althusser and Foucault among others, it may be called the dominant ideology of our age. Its hold on the English-speaking world has been noted by both conservative and libertarian writers, and is subject to an increasingly lively debate.

Sean Gabb, “Market Behaviour in the Ancient World: An Overview of the Debate”, 2008-05.

April 3, 2017

Ici Londres: Karl Marx didn’t get a single thing right

Published on 22 Mar 2017