Mark Steyn on the establishment GOP’s attempt to run the 2024 campaign as though nothing has changed other than the calendar:

I mentioned on Monday that on his long-running Radio Derb John Derbyshire drew his listeners’ attention to an observation of yours truly:

I can’t improve on Steyn — nobody can — so I’ll just quote him from that piece.

I always feel Derb thinks I’m a bit of a pantywaist on the hardcore issues, but in today’s America even a reasonably sentient pantywaist should be able to get to the nub of the issue. Here’s the bit Derb quoted:

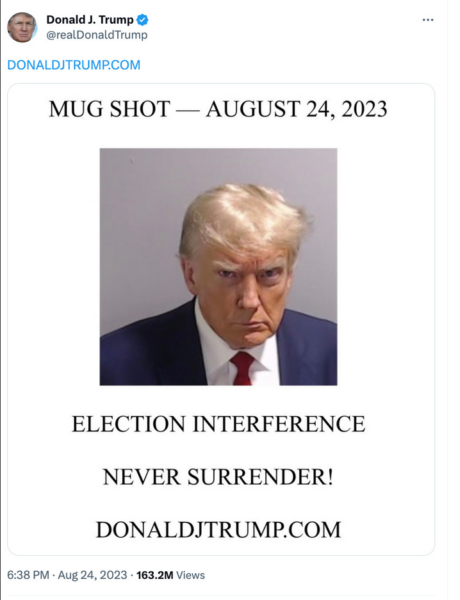

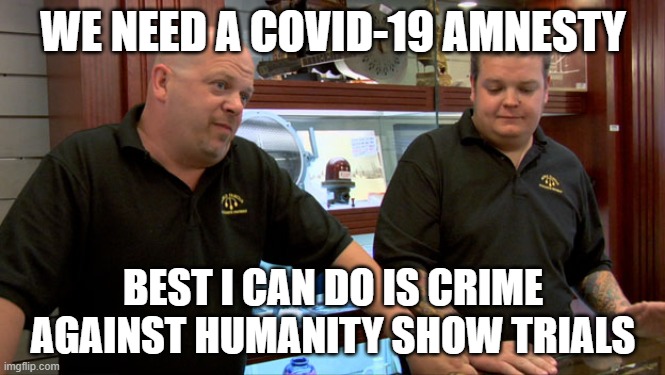

So two years later the American Right still talks about the justice system and the election campaign as if either term means what it does in functioning societies. As I said above, I don’t intend to comment on this week’s Trump indictment either, nor do I wish to talk about who would make the best president, who has the best platform, who has the skill-set to implement the platform … That would be all well and good if we were in, say, France, but, when the dirty stinking rotten corrupt U.S. justice system is criminalizing political opposition, there’s no point pretending this is a normal situation, right?

“There’s no point pretending this is a normal situation, right?” And yet at least three-quarters of the candidates in that Republican debate insisted on doing just that: This is just a normal quadrennial election in the greatest country in the history of countries where we’re renowned around the planet for our uniquely peaceful “peaceful transfer of power”, etc, etc.

Sorry, I don’t buy that — and evidently nor does the GOP base. Which is why Trump has a forty-point lead over his nearest rival, and Nikki Haley’s alleged triumph on stage in that debate has seen her numbers soar to — stand well back! — 6.1 per cent. The avowedly normal vice-president, senator and three governors nipping at her heels can barely muster ten percent between them. There don’t seem to be a lot of takers for “pretending this is normal”.

John Derbyshire quoted me in the context of the latest sentences on the January 6th “insurrectionists”. Dominic Pezzola broke a window at the Capitol and was given ten years; the government had asked for twenty. Joseph Biggs moved a crowd-control barrier and was sentenced to seventeen years; the government had wanted him banged up for thirty-three.

So the prosecutors and the judges seem to have reached a cozy understanding that, whatever sentence the former demand, the Court will be totally reasonable and cut in half. You want another? The feds demanded thirty years for Zachary Rehl; the judge gave him fifteen. And this is after two-and-a-half years in gaol awaiting their “constitutional right” (don’t wave that constitution at me!) to a speedy trial.

Oops, wait, I spoke too soon. The US Attorney wanted thirty-three years for Proud Boys leader Enrique Tarrio, but this time the judge decided to up it to two-thirds of the feds’ demand: twenty-two years. For a guy who wasn’t in Washington on January 6th.

All this of course in an ugly and violent land where actual career criminals who like to beat up disabled women with their own canes have the run of the playground. And with the connivance and support of the Democrat Party, even when very occasionally it all goes wrong for one of their own.

Oh, well. Mr Tarrio is a Proud Boy. I’m not really a Proud Boys type, if only because their founder, Gavin McInnes, has been a bit of an arse about me re Cockwombling Cary Katz and the CRTV cases. Still, I’m all about first principles — and a decade for breaking a window is not, even by lousy American standards, the verdict of a “justice” system.