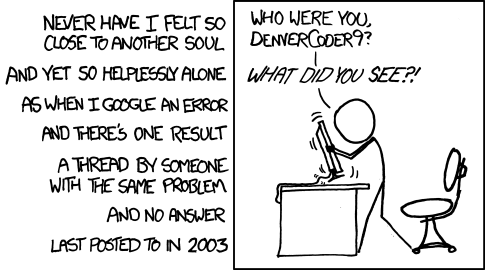

This xkcd installment is amazingly accurate, at least based on my experiences:

Wisdom of the Ancients

Remember to mouse-over the cartoon: you’re missing at least half the humour if you don’t read the mouse-over text of any xkcd cartoon.

This xkcd installment is amazingly accurate, at least based on my experiences:

Wisdom of the Ancients

Remember to mouse-over the cartoon: you’re missing at least half the humour if you don’t read the mouse-over text of any xkcd cartoon.

GCHQ grew out of the WW2 code-breaking group based at Bletchly Park and is the British equivalent of the NSA. Recently it was announced that GCHQ will start offering its expertise to private businesses:

Some of the secret technologies created at the government’s giant eavesdropping centre GCHQ are to be offered to private industry as part of new cyber security strategy being unveiled by ministers on Friday.

The idea is likely to be one of the most contentious in the plans, which could lead to the government being paid substantial sums for software developed by the intelligence agency based in Cheltenham.

Opening up GCHQ to commercial opportunities will not deflect it from defending national security, which remains its priority, ministers argue, and the agency has insisted it will not be side-tracked.

However, the new cyber strategy makes clear that the dangers posed by espionage and crime on the web cannot be faced without better co-operation between the two sectors, and that they will have to work together more closely in future.

It’s not quite what it seems like:

My weekly technology law column [. . .] notes the resulting decision seemed to cause considerable confusion as some headlines trumpeted a “Canadian compromise,” while others insisted that the CRTC had renewed support for UBB. Those headlines were wrong. The decision does not support UBB at the wholesale level (the retail market is another story) and the CRTC did not strike a compromise. Rather, it sided with the independent Internet providers by developing the framework the independents had long claimed was absent — one based on the freedom to compete.

For many years, Canada has maintained policies theoretically designed to foster an independent ISP market. Those policies required the large Internet providers such as Bell and Rogers to make part of their network available to independent competitors. Since the large providers were not supportive of increased competition, the CRTC established mandatory rules on access, pricing, and speed matching.

Yet despite years of tinkering with the rules, the independents only garnered a tiny percentage of the marketplace (approximately six percent). The UBB issue illustrates why the independent providers have struggled since the original proposal would have allowed Bell to charge independent ISPs based on the amount of data used.

While that sounds reasonable, the cost of running a network has little to do with the amount of data consumed. Rather, it is linked to the capacity of the network — the fatter the pipe, the greater the cost, irrespective of how much data is actually consumed.

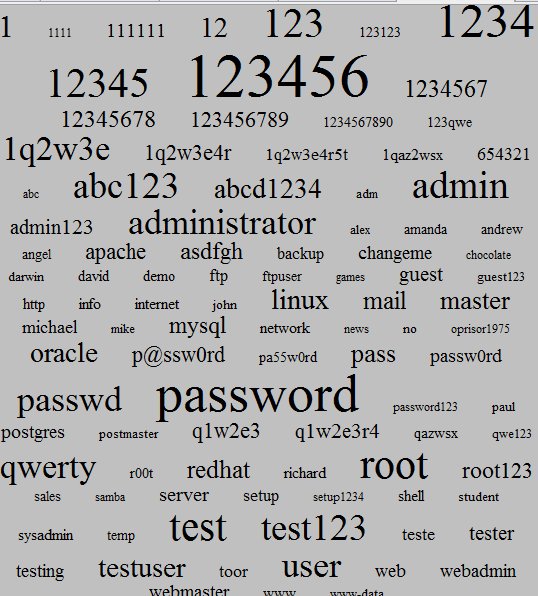

Do you use any of the following terms as your password? If so, congratulations, you’re helping keep the rest of us from being as easily hacked as you are:

1. password

2. 123456

3. 12345678

4. qwerty

5. abc123

6. monkey

7. 1234567

8. letmein

9. trustno1

10. dragon

11. baseball

12. 111111

13. iloveyou

14. master

15. sunshine

16. ashley

17. bailey

18. passw0rd

19. shadow

20. 123123

21. 654321

22. superman

23. qazwsx

24. michael

25. football

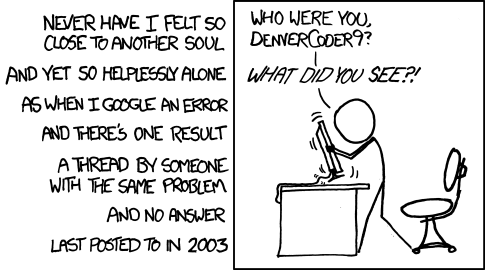

This list is from SplashData, who produce (among other things) a password-keeper utility. Last year, Gawker published the 50 top passwords in a graphic:

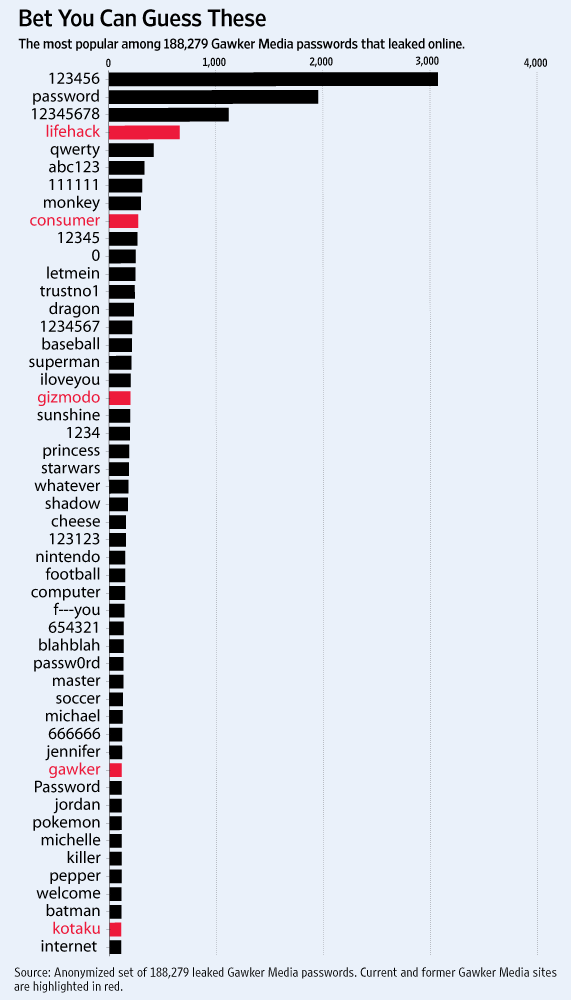

Here’s a word cloud from an earlier post on passwords:

Other posts on this topic: opportunities for humour with your bank’s secret questions, xkcd on the paradox of passwords, Passwords and the average user, More on passwords, And yet more on passwords, and Practically speaking, the end is in sight for passwords.

If you don’t already associate SOPA with evil, Michael Geist explains why you should:

The U.S. Congress is currently embroiled in a heated debated over the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA), proposed legislation that supporters argue is needed combat online infringement, but critics fear would create the “great firewall of the United States.” SOPA’s potential impact on the Internet and development of online services is enormous as it cuts across the lifeblood of the Internet and e-commerce in the effort to target websites that are characterized as being “dedicated to the theft of U.S. property.” This represents a new standard that many experts believe could capture hundreds of legitimate websites and services.

For those caught by the definition, the law envisions requiring Internet providers to block access to the sites, search engines to remove links from search results, payment intermediaries such as credit card companies and Paypal to cut off financial support, and Internet advertising companies to cease placing advertisements. While these measures have unsurprisingly raised concern among Internet companies and civil society groups (letters of concern from Internet companies, members of the US Congress, international civil liberties groups, and law professors), [. . .] the jurisdictional implications demand far more attention. The U.S. approach is breathtakingly broad, effectively treating millions of websites and IP addresses as “domestic” for U.S. law purposes.

The long-arm of U.S. law manifests itself in at least five ways in the proposed legislation.

Brendan O’Neill thinks much better of women than those pushing for censorship (or worse):

One of the great curiosities of modern feminism is that the more radical the feminist is, the more likely she is to suffer fits of Victorian-style vapours upon hearing men use coarse language. Andrea Dworkin dedicated her life to stamping out what she called “hate speech” aimed at women. The Slutwalks women campaigned against everything from “verbal degradation” to “come ons”. And now, in another hilarious echo of the 19th-century notion that women need protecting from vulgar and foul speech, a collective of feminist bloggers has decided to “Stamp Out Misogyny Online”. Their deceptively edgy demeanour, their use of the word “stamp”, cannot disguise the fact that they are the 21st-century equivalent of Victorian chaperones, determined to shield women’s eyes and cover their ears lest they see or hear something upsetting.

According to the Guardian, these campaigners want to stamp out “hateful trolling” by men — that is, they want an end to the misogynistic bile and spite that allegedly clogs up their email inboxes and internet discussion boards. Leaving aside the question of who exactly is supposed to do all this “stamping out” of heated speech — The state? Well, who else could do it? — the most striking thing about these fragile feminists’ campaign is the way it elides very different forms of speech. So the Guardian report lumps together “threats of rape”, which are of course serious, with “crude insults” and “unstinting ridicule”, which are not that serious. If I had a penny for every time I was crudely insulted on the internet, labelled a prick, a toad, a shit, a moron, a wide-eyed member of a crazy communist cult, I’d be relatively well-off. For better or worse, crudeness is part of the internet experience, and if you don’t like it you can always read The Lady instead.

Ars Technica has what should be the final legal chapter in the Righthaven saga:

Looks like it’s time to turn out the lights on Righthaven. The US Marshal for the District of Nevada has just been authorized by a federal court to use “reasonable force” to seize $63,720.80 in cash and/or assets from the Las Vegas copyright troll after Righthaven failed to pay a court judgment from August 15.

Righthaven made a national name for itself by suing mostly small-time bloggers and forum posters over the occasional copied newspaper article, initially going so far as to demand that targeted websites turn over their domain names to Righthaven. The several hundred cases went septic on Righthaven, however, once it became clear that Righthaven didn’t own the copyrights over which it was suing. Righthaven, ailing, was soon buffeted by negative court decisions as a result.

[. . .]

The appeals court has refused to act on Righthaven’s request to delay its August judgment further, and the money was due last Friday. When it didn’t show up, Randazza Legal Group went back to the Nevada District Court to request a Writ of Execution to use the court’s enforcers, the US Marshals, to collect the money. The court clerk issued the writ today, and Righthaven’s $34,045.50 judgment has now ballooned to $63,720.80 with all the additional costs and fees from the delay.

I spoke to Marc Randazza this evening, who tells me, “We’re going to enlist the US Marshal in marking sure this court’s order has some meaning.” He looks forward to heading over to Righthaven’s offices as soon as possible. Should Righthaven not have the cash in its bank accounts, the writ allows Randazza to “identify to the US Marshal or his representative assets that are to be seized to satisfy the judgment/order.”

The degree of threat that Righthaven and other lawfare groups posed to bloggers and anyone else who quoted material on the internet was discussed back in May.

The headline on this article says it all: E-PARASITES Bill: ‘The End Of The Internet As We Know It’.

We already wrote about the ridiculously bad E-PARASITES bill (the Enforcing and Protecting American Rights Against Sites Intent on Theft and Exploitation Act), but having now had a chance go to through the full bill a few more times, there are even more bad things in there that I missed on the first read-through. Now I understand why Rep. Zoe Lofgren’s first reaction to this bill was to say that “this would mean the end of the Internet as we know it.”

She’s right. The more you look at the details, the more you realize how this bill is an astounding wishlist of everything that the legacy entertainment gatekeepers have wanted in the law for decades and were unable to get. It effectively dismantles the DMCA’s safe harbors, what’s left of the Sony Betamax decision, puts massive liability on tons of US-based websites, and will lead to widespread blocking of websites and services based solely on accusations of some infringement. It’s hard to overstate just how bad this bill is.

And, while its mechanisms are similar to the way China’s Great Firewall works (by putting liability on service providers if they fail to block sites), it’s even worse than that. At least the Chinese Great Firewall is determined by government talking points. The E-PARASITES bill allows for a massive private right of action that effectively lets any copyright holder take action against sites they don’t like. (Oh, and the bill is being called both the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) and E-PARASITES (which covers the PROTECT IP-like parts of the bill, SOPA refers to the larger bill that also includes the felony streaming part).

Cory Doctorow points out that no “adult content” filter is a replacement for parental guidance and supervision:

Last week’s announcement of a national scheme to “block adult content at the point of subscription” (as the BBC’s website had it) was a moment of mass credulity on the part of the nation’s media, and an example of how complex technical questions and hot-button save-the-children political pandering are a marriage made in hell when it comes to critical analysis in the press.

Under No 10’s proposal, the UK’s major ISPs — BT, Sky, TalkTalk and Virgin — will invite new subscribers to opt in or out of an “adult content filter.” But for all the splashy reporting on this that dominated the news cycle, no one seemed to be asking exactly what “adult content” is, and how the filters’ operators will be able to find and block it.

Adult content covers a lot of ground. While the media of the day kept mentioning pornography in this context, existing “adult” filters often block gambling sites and dating sites (both subjects that are generally considered “adult” but aren’t anything like pornography), while others block information about reproductive health and counselling services aimed at GBLT teens (gay, bisexual, lesbian and transgender).

[. . .]

The web is vast, and adult content is a term that is so broad as to be meaningless. Even if we could all agree on what adult content was, there simply aren’t enough bluenoses and pecksniffs to examine and correctly classify even a large fraction of the web, let alone all of it (despite the Radio 4 newsreader’s repeated assertion that the new filter would “block all adult content”.)

What that means is that parents who opt their families into the scheme are in for a nasty shock: first, when their kids (inevitably) discover the vast quantities of actual, no-fooling pornography that the filter misses; and second, when they themselves discover that their internet is now substantially broken, with equally vast swathes of legitimate material blocked.

Cory Doctorow reports on remarks by the head of the UN World Intellectual Property Organization:

Last June, the Swiss Press Club held a launch for the Global Innovation Index at which various speakers were invited to talk about innovation. After the head of CERN and the CEO of the Internet Society spoke about how important it was that the Web’s underlying technology hadn’t been patented, Francis Gurry, the Director General of the UN’s World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), took the mic to object.

In Gurry’s view, the Web would have been better off if it had been locked away in patents, and if every user of the Web had needed to pay a license fee to use it (and though Gurry doesn’t say so, this would also have meant that the patent holder would have been able to choose which new Web sites and technologies were allowed, and would have been able to block anything he didn’t like, or that he feared would cost him money).

This is a remarkable triumph of ideology over evidence. The argument that there wasn’t enough investment in the Web is belied by the fact that a) the Web attracted more investment than any of the network service technologies that preceded it (by orders of magnitude), and; b) that the total investment in the Web is almost incalculably large. The only possible basis for believing that the Web really would have benefited from patents is a blind adherence to the ideology that holds that patents are always good, no matter what.

Just imagine: instead of our current anarchic, idiosyncratic-but-still-amazingly-useful Web, we’d have a bureaucratically regulated superset of the old walled garden models like Compuserve, where innovation was stifled long before it got into the users’ hands.

Andrew Orlowski posts some of his comments at a recent (British) Conservative Conference Fringe discussion on digital policy:

You all know what an entrepreneur is. But who has heard of the word nontrepreneur?

There were amused and bemused looks.

Well you’re going to be hearing it a lot.

We’re in an exciting time for the internet. This great wave of utopian rhetoric and getting everyone online, for the last 15 years, has come to an end. Almost everyone who wants to be online is online. Something quite new and interesting has happened in the past three years, people are beginning to pay for stuff.

The internet today lacks markets and it’s half-finished. The platforms and infrastructure that recognise and create value aren’t there.

Now words come to define political eras and philosophies, and the last ten years were defined by words like ‘beaconicity’ and ‘targets’ and all these agencies spending other people’s money. I have a horrible feeling that Cameron’s technology policy, despite being guided by people with strong classical liberal instincts, will be defined by the fluff of Silicon Roundabout.

Silicon Roundabout is, essentially, a prank on the media. Let’s see who’s involved. You’ve got what I call faux capitalists — people who want to be thought of as capitalists but are terrified of risk and don’t back ambitious high-risk ventures. You’ve got entrepreneurs who can’t run a business. And you’ve got programmers who can’t program. All looking for each other. Then there’s a vast army of hangers-on: mentors, facilitators. And they all socialise endlessly, instead of doing any work. The socialising is work.

This does not create wealth.

As soon as we start to “un-fetishise” this myth of two guys in a garage, and start to think more seriously about, say, payment platforms or credit systems that make buying stuff nice and easy, as easy as real life, then we’ll create markets. You won’t get this from Shoreditch.

That’s a bit of good news on the civil liberties front:

A controversial Internet surveillance bill has been omitted from the federal Conservative party’s proposed crime legislation.

Today, Canadian Minister of Justice and Attorney General Rob Nicholson held a press conference to introduce the Conservatives’ promised omnibus crime act, titled The Safe Streets and Communities Act, which focuses on crime and terrorism. However, an expected component of the act regarding Internet surveillance known as “Lawful Access” legislation was nowhere to be found.

The set of Lawful Access bills would have warranted Canadian law enforcement and intelligence agencies the power to acquire the personal information and activity of web users from internet service providers (ISPs). ISPs would also be required by an additional provision to install surveillance equipment on their networks.

The legislation would essentially give law enforcement the ability to track people online without having to obtain a warrant. The federal NDP and Green parties, and civil liberties groups among others decried the bill as overly-invasive, dangerous and potentially costly for internet users.

That’s the good news. The rest of the bill, as Grace Scott points out, is awash with “tough on crime” noises:

The Safe Streets and Communities Act will increase penalties for sex offenders, those caught with possession or producing illicit drugs for the purposes of trafficking, and intends to implement tougher sentencing on violent and repeat youth crime. It also plans to eliminate the use of conditional sentences, or house arrest, for serious and violent crimes.

Although the new .xxx domain is available for registration, you probably won’t find a google.xxx or a microsoft.xxx domain:

Businesses in the adult entertainment industry — and outside of it — from today have the opportunity to register or block .xxx domain names that match their trademarks.

ICM Registry, which has operated .xxx since it signed a contract with ICANN earlier this year, has launched a three-pronged “sunrise period” that will run for the next 52 days.

The pre-launch phase is designed to allow trademark owners to either snag a .xxx domain if they’re in the porn business, or to pay to have their brands blocked forever if they’re not.

While the sunrise has been characterised by many critics as a “shakedown”, ICM is doing things a little differently to domain registries that have launched in the past.

As we have previously reported, a big chunk of the 15,000 names ICM has reserved match the names of celebrities — actors, politicians, sportsmen, singers — to prevent embarrassment.

It did not extend the same courtesy to big corporate brands.

However, uniquely to .xxx, any non-porn company wishing to take their .xxx name out of circulation permanently needs only pay a one-time fee, rather than paying up-front and renewing annually.

Powered by WordPress