Polyus

Published 10 Jan 2019The Avian 2/180 Gyroplane was a project that rose from the ashes of the Avro Arrow cancellation. Five former employee formed their own company and set out to build a new kind of autogyro. Their Gyroplane could take off and land vertically and could fly at speeds up to 265 km/h. Although it never made any sales, it is an impressive project that deserves some attention.

(Also sorry for the flickering in the video. I did my best to limit it but the source video didn’t give me much to work with.)

(more…)

February 9, 2023

Attractive VTOL autogyro with unrealised potential; the story of the Avian 2/180 Gyroplane

February 4, 2023

A lobster tale (that does not involve Jordan Peterson)

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes relates some of his recent research on the Parliament of 1621 (promising much more in future newsletters) and highlights one of the Royal monopolies that came under challenge in the life of that Parliament:

One of the great things about the 1621 Parliament, as a historian of invention, is that MPs summoned dozens of patentees before them, to examine whether their patents were “grievances” — illegal and oppressive monopolies that ought to be declared void. Because of these proceedings, along with the back-and-forth of debate between patentees and their enemies, we can learn some fascinating details about particular industries.

Like how 1610s London had a supply of fresh lobsters. The patent in question was acquired in 1616 by one Paul Bassano, who had learned of a Dutch method of keeping lobsters fresh — essentially, to use a custom-made broad-bottomed ship containing a well of seawater, in which the lobsters could be kept alive. Bassano, in his petitions to the House of Commons, made it very clear that he was not the original inventor and had imported the technique. This was exactly the sort of thing that early monopoly patents were supposed to encourage: technological transfer, and not just original invention.

The problem was that the patent didn’t just cover the use of the new technique. It gave Bassano and his partners a monopoly over all imported lobsters too. This was grounded in a kind of industrial policy, whereby blocking the Dutch-caught lobsters would allow Bassano to compete. He noted that Dutch sailors were much hardier and needed fewer provisions than the English, and that capital was available there at interest rates of just 4-5%, so that a return on sales of just 10% allowed for a healthy profit. In England, by comparison, interest rates of about 10% meant that he needed a return on sales of at least 15%, especially given the occasional loss of ships and goods to the capriciousness of the sea — he noted that he had already lost two ships to the rocks.

At the same time, patent monopolies were designed to nurture expertise. Bassano noted that he still needed to rely on the Dutch, who were forced to sell to the English market either through him or by working on his ships. But he had been paying his English sailors higher wages, so that over time the trade would come to be dominated by the English. (This training element was a key reason that most patents tended to be given for 14 or 21 years — the duration of two or three apprenticeships — though Bassano’s was somewhat unusual in that it was to last for a whopping 31.)

But the blocking of competing imports — especially foodstuffs, which were necessaries of life — could be very controversial, especially when done by patent rather than parliamentary statute. Monopolies could lawfully only be given for entirely new industries, as they otherwise infringed on people’s pre-existing practices and trades. Bassano had worked out a way to avoid complaints, however, which was essentially to make a deal with the fishmongers who had previously imported lobsters, taking them into his partnership. He offered them a win-win, which they readily accepted. In fact, the 1616 patent came with the explicit support of the Fishmongers’ Company.

It sounds like it became a large enterprise, and I suspect that it probably did lower the price of lobsters in London, bringing them in regularly and fresh. With a fleet of twenty ships, and otherwise supplementing their catch with those caught by the Dutch, Bassano boasted of how he was able to send a fully laden ship to the city every day (wind-permitting). This stood in stark contrast to the state of things before, when a Dutch ship might have arrived with a fresh catch only every few weeks or months, and when they felt that scarcity would have driven the prices high.

February 2, 2023

MAC Model 1947 Prototype SMGs

Forgotten Weapons

Published 12 Oct 2022Immediately upon the liberation of France in 1944, the French military began a process of developing a whole new suite of small arms. As it applied to SMGs, the desire was for a design in 9mm Parabellum (no more 7.65mm French Long), with an emphasis on something light, handy, and foldable. All three of the French state arsenals (MAC, MAS, and MAT) developed designs to meet the requirement, and today we are looking at the first pair of offerings from Chatellerault (MAC). These are the 1947 pattern, a very light lever-delayed system with (frankly) terrible ergonomics.

Many thanks to the French IRCGN (Criminal Research Institute of the National Gendarmerie) for generously giving me access to film these unique specimens for you!

Today’s video — and many others — have been made possible in part by my friend Shéhérazade (Shazzi) Samimi-Hoflack. She is a real estate agent in Paris who specializes in working with English-speakers, and she has helped me arrange places to stay while I’m filming in France. I know that exchange rates make this a good time for Americans to invest in Europe, and if you are interested in Parisian real estate I would highly recommend her. She can be reached at: samimiconsulting@gmail.com

(Note: she did not pay for this endorsement)

(more…)

February 1, 2023

What’s the Greatest Machine of the 1980s … the FV107 Scimitar?

Engine Porn

Published 19 Jan 2015Light, agile and very fast on all types of terrain, the fabulous Scimitar FV107 armoured reconnaissance vehicle was developed by car manufacturer Alvis, who were asked to build a fast military vehicle that was light enough to be airdropped — simply not an option for full sized battle tanks at the time, which averaged around 13 tonnes. [NR: I think they mean “light tanks” here, as MBTs of the era would have been more like 50+ tons.]

Alvis got the weight down to under 8 tonnes by using a new type of aluminium alloy and minimising armour rating in favour of speed. They built the Scimitar around a 220 horsepower, six cylinder, 4.2 litre Jaguar sports car engine with ground-breaking transmission that allowed differential power to each set of tracks. The result was a sports car of the the military world that might not be the toughest in the field, but could race its way out of trouble at speeds of up to 70 miles an hour.

What makes it great: A revolutionary armoured vehicle that brought the very best of British sports car performance to the battlefield.

Time Warp: The Scimitar was the only armoured vehicle to be used by the British Army in the Falklands War.

This short film features Chris Barrie taking the Scimitar for a spin.

(more…)

January 29, 2023

France’s Ultimate WW1 Selfloading Rifle: The RSC-1918

Forgotten Weapons

Published 14 Sept 2017The French RSC-1917 semiauto rifle was a major step forward in arms technology during World War One, offering a reliable and effective self-loading rifle for issue to squad leaders, expert marksmen, and other particularly experienced and effective troops. No other military was able to field a semiauto combat shoulder rifle during this was in anything but very limited numbers. However, the RSC-1917 definitely had some shortcomings:

– It was just too long, at the same size as the Lebel

– The specialized clip was a logistical problem

– The gas system was fragile and difficult to clean or disassemble

– The magazine cover was easily damagedThese issues were all addressed in the Model 1918 upgrade of the rifle, although it was too late to see active service in the Great War. The new pattern was substantially shorter (both the stock and barrel), it used the standard Berthier 5-round clip, it had a substantially strengthened magazine cover, and a much improved gas system.

Today, we will compare the various features of the 1917 and 1918 rifles, and disassemble the 1918 gas system to show how it worked.

(more…)

January 22, 2023

Where The British Army Figured Out Tanks: Cambrai 1917

The Great War

Published 20 Jan 2023The Battle of Cambrai in 1917 didn’t have a clear winner, but the conclusions that Germany and Britain drew from it, particularly about the use of the tank (in combination with other arms), would have far reaching consequences in 1918.

(more…)

January 18, 2023

Ask Ian: Why No German WW2 50-Cal Machine Guns? (feat. Nick Moran)

Forgotten Weapons

Published 20 Sep 2022From Nathaniel on Patreon:

“Why didn’t Germany or Axis powers have a machine gun similar to the American M2?”Basically, because everyone faced the choice of a .50 caliber machine gun or 20mm (or larger) cannons for anti-aircraft use, and most people chose the cannons — including Germany. There were some .50 caliber machine guns adopted by Axis powers, most notably the Hotchkiss 1930, a magazine-fed 13.2mm gun that was used by both Italy and Japan (among others). However, the use of the .50 caliber M2 by the US was really a logistical holdover form the interwar period. The M2 remained in production because it was adopted by US Coastal Artillery as a water-cooled anti-aircraft gun, and commercial sales by Colt were slim but sufficient to keep the gun in development through the 20s and 30s. It was used as a main armament in early American armor, but obsolete in this role when the war broke out.

However, with the gun in production and no obvious domestic 20mm design, the US chose to simply make an astounding number of M2s and just dump them everywhere, from Jeeps to trucks to halftracks to tanks to self-propelled guns. And that’s not considering the 75% of production that went to coaxial and aircraft versions …

Anyway, back to the question. The German choice for antiaircraft use was the 20mm and 37mm Flak systems, and not a .50 MG on every tank turret. And so, there was really no motive to develop such a gun. The Soviets did choose to go the US route, though, and developed the DShK-38 for the same role as the US M2 — although it was made in only a tiny fraction of the quantity of the M2.

(more…)

January 8, 2023

Caesar Salad and Satan’s Playground

The History Guy: History Deserves to Be Remembered

Published 7 Sep 2022The rare example of a food fad that has maintained its popularity, the tangy dressing on romaine lettuce salad has a history as rich as a coddled egg, involving multiple nations, a bevy of movie stars, an infamous American divorcee, a disputed origin story, and, prominently, alcohol. And, perhaps surprising to many, is unrelated to the notorious Roman dictator.

(more…)

January 5, 2023

Tank Chats #162 | Springer | The Tank Museum

The Tank Museum

Published 2 Sep 2022Join Curator David Willey in his latest Tank Chat as he delves into the Springer, a German demolition vehicle.

(more…)

January 4, 2023

The First Modern Military Rifle: The Modele 1886 Lebel

Forgotten Weapons

Published 5 Dec 2017The Lebel was a truly groundbreaking development in military small arms, being the first rifle to use smokeless powder. This gave it — and in turn the French infantry — a massive advantage in range over everyone else in the world at the time. This advantage was short-lived, but the French did their best to exploit it.

French chemist Paul Vielle successfully developed his smokeless powder (“poudre B“) formula in 1884, and French ordnance spent 1885 experimenting with different calibers of small bore bullet to see what would work best. They also began looking at rifle actions to use, including specifically the Remington-Lee and the Mannlicher. However, a new Minister of War was appointed in January of 1886 and he demanded a completed prototype rifle and ammunition be completed by May 1886. This was a nearly impossibly short deadline to meet, and it meant that the Ordnance officers could not possibly develop a wholly new rifle, and instead would have to modify something already in the inventory.

The only suitable option was the Model 1884/5, a combination of the Gras bolt and Kropatschek tube magazine. The new smokeless cartridge was made by simply necking down the 11mm Gras round, and the 1884 rifle was given a new barrel in 8mm and a new dual-locking-lug bolt head to accommodate the high chamber pressure of the new powder. The result was the Lebel, and it was formally accepted in April 1887 after a relatively short period of testing. The weapon may not have been used the most advanced elements, but it was without any doubt the foremost military rifle in the world at the time, by a substantial margin.

The three main French state arsenals of St Etienne, Chatellerault, and Tulle would all tool up to produce the Lebel, and by the end of 1892 approximately 2.8 million had been produced, enough to equip the entire Army. The rifle would remain in service as France’s primary infantry rifle until World War One, would be declared obsolete in 1920, and remain in inventory and in use until the end of World War Two.

(more…)

January 3, 2023

Debunking the Myths of Leonardo da Vinci

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 9 Aug 2022

(more…)

December 20, 2022

The forgotten Thomas Savery

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes remembers the work of inventor Thomas Savery:

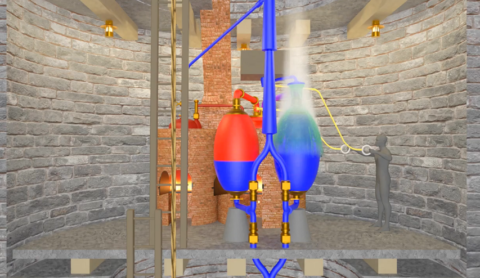

Screenshot from “Savery’s Miners Friend – 1698”, a YouTube video by Guy Janssen (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dt5VvrEIj8w)

We know surprisingly little about Thomas Savery — the inventor of the first widely-used steam engine. Unfortunately, his achievements were almost immediately overshadowed by the engine of Thomas Newcomen, and so he’s often only mentioned as a sort of afterthought — a loose and rather odd-seeming pebble before the firmer stepping stones of Newcomen, Watt, Trevithick, and other steam engine pioneers in the standard and simple narratives of technological progress that people like to tell. I’ve often seen Savery’s name omitted entirely.

He is even neglected by the experts. The Newcomen Society, of which I am a new member, has an excellent journal — it is the best place to find scholarly detail about all steam pioneers, and about the history of engineering in general. Yet even it only mentions Savery in passing. In over a century, Savery has been named in the titles of just three of its articles, and the last was published in 1986.

I think Savery is extremely under-rated, and deserves to be studied more. Fortunately, we do know quite a bit about the engine he designed, which he intended primarily for raising the water out of mines. Steam was admitted into a chamber, and then sprayed with cold water to condense it. This caused mine water to be sucked up a pipe beneath it, by creating a partial vacuum within the chamber and thus exploiting the relative pressure of the atmosphere on the surface of the mine water. Then, hot steam was readmitted to the chamber, this time pushing the raised water further up through another pipe above. Two chambers, the one sucking while the other pushed, created a continuous flow. (Video here.) We have dozens of images and technical descriptions of Savery’s engine, as it continued to be used for decades, especially in continental Europe.

But we know essentially nothing about Savery’s background, training, inspiration, or profession, and most of the supposedly known biographical details we have for him are simply wrong. There is no evidence that he was a “military engineer” or a “trenchmaster”, for example — mere speculation that has been repeated so often as to take on the appearance of fact. Savery simply appears out of nowhere in the 1690s, with his inventions almost fully formed.

Yet in Savery’s own writings we can see a few tantalising hints of how he thought, including some flashes of brilliance. I kept coming across them by chance, when investigating various energy-related themes with Carbon Upcycling. Take the following aside, from Savery’s 1702 prospectus for his steam engine: “I have only this to urge, that water in its fall from any determinate height, has simply a force answerable and equal to the force that raises it”. Savery here seems to be hinting at some idea of the conservation of energy, and perhaps of a theoretical maximum efficiency — in a phrase that is remarkably similar to that used by the pioneers of water wheel theory half a century later, and to Sadi Carnot when he applied the same ideas to early thermodynamics.

Savery, frustratingly, doesn’t expand any further on the point, except to then casually mention the notions of both mechanical work and horsepower — over eighty years before James Watt. Savery noted that when an engine will raise as much water as two horses can in the same time, “then I say, such an engine will do the work or labour of ten or twelve horses” — ten horsepower, rather than two, because you’d need a much larger team of horses from which to rotate fresh ones while the others rested, to keep raising water as continuously as the force of a stream could turn a water-wheel, or his steam engine could pump. (Incidentally, Watt wasn’t even the second person to use horsepower — the same concept was also mentioned by John Theophilus Desaguliers in the 1720s and John Smeaton in the 1770s. Watt just managed to get all the credit later on. Perhaps watts should really be called saveries, even if he was less precise.)

December 18, 2022

QotD: Citation systems and why they were developed

For this week’s musing I wanted to talk a bit about citation systems. In particular, you all have no doubt noticed that I generally cite modern works by the author’s name, their title and date of publication (e.g. G. Parker, The Army of Flanders and the Spanish Road (1972)), but ancient works get these strange almost code-like citations (Xen. Lac. 5.3; Hdt. 7.234.2; Thuc. 5.68; etc.). And you may ask, “What gives? Why two systems?” So let’s talk about that.

The first thing that needs to be noted here is that systems of citation are for the most part a modern invention. Pre-modern authors will, of course, allude to or reference other works (although ancient Greek and Roman writers have a tendency to flex on the reader by omitting the name of the author, often just alluding to a quote of “the poet” where “the poet” is usually, but not always, Homer), but they did not generally have systems of citation as we do.

Instead most modern citation systems in use for modern books go back at most to the 1800s, though these are often standardizations of systems which might go back a bit further still. Still, the Chicago Manual of Style – the standard style guide and citation system for historians working in the United States – was first published only in 1906. Consequently its citation system is built for the facts of how modern publishing works. In particular, we publish books in codices (that is, books with pages) with numbered pages which are typically kept constant in multiple printings (including being kept constant between soft-cover and hardback versions). Consequently if you can give the book, the edition (where necessary), the publisher and a page number, any reader seeing your citation can notionally go get that edition of the book and open to the very page you were looking at and see exactly what you saw.

Of course this breaks down a little with mass-market fiction books that are often printed in multiple editions with inconsistent pagination (thus the endless frustration with trying to cite anything in A Song of Ice and Fire; the fan-made chapter-based citation system for a work without numbered or uniquely named chapters is, I must say, painfully inadequate.) but in a scholarly rather than wiki-context, one can just pick a specific edition, specify it with the facts of publication and use those page numbers.

However the systems for citing ancient works or medieval manuscripts are actually older than consistent page numbers, though they do not reach back into antiquity or even really much into the Middle Ages. As originally published, ancient works couldn’t have static page numbers – had they existed yet, which they didn’t – for a multitude of reasons: for one, being copied by hand, the pagination was likely to always be inconsistent. But for ancient works the broader problem was that while they were written in books (libri) they were not written in books (codices). The book as a physical object – pages, bound together at a spine – is more technically called a codex. After all, that’s not the only way to organize a book. Think of a modern ebook for instance: it is a book, but it isn’t a codex! Well, prior to codex becoming truly common in third and fourth centuries AD, books were typically written on scrolls (the literal meaning of libri, which later came to mean any sort of book), which notably lack pages – it is one continuous scroll of text.

Of course those scrolls do not survive. Rather, ancient works were copied onto codices during Late Antiquity or the Middle Ages and those survive. When we are lucky, several different “families” of manuscripts for a given work survive (this is useful because it means we can compare those manuscripts to detect transcription errors; alas in many cases we have only one manuscript or one clearly related family of manuscripts which all share the same errors, though such errors are generally rare and small).

With the emergence of the printing press, it became possible to print lots of copies of these works, but that combined with the manuscript tradition created its own problems: which manuscript should be the authoritative text and how ought it be divided? On the first point, the response was the slow and painstaking work of creating critical editions that incorporate the different manuscript traditions: a main text on the page meant to represent the scholar’s best guess at the correct original text with notes (called an apparatus criticus) marking where other manuscripts differ. On the second point it became necessary to impose some kind of organizing structure on these works.

The good news is that most longer classical works already had a system of larger divisions: books (libri). A long work would be too long for a single scroll and so would need to be broken into several; its quite clear from an early point that authors were aware of this and took advantage of that system of divisions to divide their works into “books” that had thematic or chronological significance. Where such a standard division didn’t exist, ancient libraries, particularly in Alexandria, had imposed them and the influence of those libraries as the standard sources for originals from which to make subsequent copies made those divisions “canon”. Because those book divisions were thus structurally important, they were preserved through the transition from scrolls to codices (as generally clearly marked chapter breaks), so that the various “books” served as “super-chapters”.

But sub-divisions were clearly necessary – a single librum is pretty long! The earliest system I am aware of for this was the addition of chapter divisions into the Vulgate – the Latin-language version of the Bible – in the 13th century. Versification – breaking the chapters down into verses – in the New Testament followed in the early 16th century (though it seems necessary to note that there were much older systems of text divisions for the Tanakh though these were not always standardized).

The same work of dividing up ancient texts began around the same time as versification for the Bible. One started by preserving the divisions already present – book divisions, but also for poetry line divisions (which could be detected metrically even if they were not actually written out in individual lines). For most poetic works, that was actually sufficient, though for collections of shorter poems it became necessary to put them in a standard order and then number them. For prose works, chapter and section divisions were imposed by modern editors. Because these divisions needed to be understandable to everyone, over time each work developed its standard set of divisions that everyone uses, codified by critical texts like the Oxford Classical Texts or the Bibliotheca Teubneriana (or “Teubners”).

Thus one cited these works not by the page numbers in modern editions, but rather by these early-modern systems of divisions. In particular a citation moves from the larger divisions to the smaller ones, separating each with a period. Thus Hdt. 7.234.2 is Herodotus, Book 7, chapter 234, section 2. In an odd quirk, it is worth noting classical citations are separated by periods, but Biblical citations are separated by colons. Thus John 3:16 but Liv. 3.16. I will note that for readers who cannot access these texts in the original language, these divisions can be a bit frustrating because they are often not reproduced in modern translations for the public (and sometimes don’t translate well, where they may split the meaning of a sentence), but I’d argue that this is just a reason for publishers to be sure to include the citation divisions in their translations.

That leaves the names of authors and their works. The classical corpus is a “closed” corpus – there is a limited number of works and new ones don’t enter very often (occasionally we find something on a papyrus or lost manuscript, but by “occasionally” I mean “about once in a lifetime”) so the full details of an author’s name are rarely necessary. I don’t need to say “Titus Livius of Patavium” because if I say Livy you know I mean Livy. And in citation as in all publishing, there is a desire for maximum brevity, so given a relatively small number of known authors it was perhaps inevitable that we’d end up abbreviating all of their names. Standard abbreviations are helpful here too, because the languages we use today grew up with these author’s names and so many of them have different forms in different languages. For instance, in English we call Titus Livius “Livy” but in French they say Tite-Live, Spanish says Tito Livio (as does Italian) and the Germans say Livius. These days the most common standard abbreviation set used in English are those settled on by the Oxford Classical Dictionary; I am dreadfully inconsistent on here but I try to stick to those. The OCD says “Livy”, by the by, but “Liv.” is also a very common short-form of his name you’ll see in citations, particularly because it abbreviates all of the linguistic variations on his name.

And then there is one final complication: titles. Ancient written works rarely include big obvious titles on the front of them and often were known by informal rather than formal titles. Consequently when standardized titles for these works formed (often being systematized during the printing-press era just like the section divisions) they tended to be in Latin, even when the works were in Greek. Thus most works have common abbreviations for titles too (again the OCD is the standard list) which typically abbreviate their Latin titles, even for works not originally in Latin.

And now you know! And you can use the link above to the OCD to decode classical citations you see.

One final note here: manuscripts. Manuscripts themselves are cited by an entirely different system because providence made every part of paleography to punish paleographers for their sins. A manuscript codex consists of folia – individual leaves of parchment (so two “pages” in modern numbering on either side of the same physical page) – which are numbered. Then each folium is divided into recto and verso – front and back. Thus a manuscript is going to be cited by its catalog entry wherever it is kept (each one will have its own system, they are not standardized) followed by the folium (‘f.’) and either recto (r) or verso (v). Typically the abbreviation “MS” leads the catalog entry to indicate a manuscript. Thus this picture of two men fighting is MS Thott.290.2º f.87r (it’s in Det Kongelige Bibliotek in Copenhagen):

MS Thott.290.2º f.87r which can also be found on the inexplicably well maintained Wiktenauer; seriously every type of history should have as dedicated an enthusiast community as arms and armor history.

And there you go.

Bret Devereaux, “Fireside Friday, June 10, 2022”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-06-10.

December 15, 2022

Kraut Space Magic: the H&K G11

Forgotten Weapons

Published 25 Dec 2018I have been waiting for a long time to have a chance to make this video — the Heckler & Koch G11! Specifically, a G11K2, the final version approved for use by the West German Bundeswehr, before being cancelled for political and economic reasons.

The G11 was a combined effort by H&K and Dynamit Nobel to produce a new rifle for the German military with truly new technology. The core of the system was the use of a caseless cartridge developed in the late 60s and early 70s by Dynamit Nobel, which then allowed H&K to design a magnificently complex action which could fire three rounds in a hyper-fast (~2000 rpm) burst and have all three bullets leave the barrel before the weapon moved in recoil.

Remarkably, the idea went through enough development to pass German trials and actually be accepted for service in the late 1980s (after a funding shutdown when it proved incapable of winning NATO cartridge selection trials a decade earlier). However, the reunification with East Germany presented a reduced strategic threat, a new surplus of East German combat rifles (AK74s), and a huge new economic burden to the combined nations and this led to the cancellation of the program. The US Advanced Combat Rifle program gave the G11 one last grasp at a future, but it was not deemed a sufficient improvement in practical use over the M16 platform to justify a replacement of all US weapons in service.

The G11 lives on, however, as an icon of German engineering prowess often referred to as “Kraut Space Magic” (in an entirely complimentary take on the old pejorative). That it could be so complex and yet still run reliably in legitimate military trials is a tremendous feat by H&K’s design engineers, and yet one must consider that the Bundeswehr may just have dodged a bullet when it ended up not actually adopting the rifle.

Many thanks to H&K USA for giving me access to the G11 rifles in their Grey Room for this video!

(more…)

November 28, 2022

Mulberry Harbours – Rhinos, Whales, Beetles, Phoenixs and Spuds against the Axis

Drachinifel

Published 13 Jul 2022Today we take a look at the artificial harbours designed, built and then installed on the Normandy beaches in 1944.

Many thanks to @Think Defence for finding and collating so many images and letting me use them! Follow them on Twitter or on their website for more interesting articles!

(more…)