Forgotten Weapons

Published 26 Feb 2012The Hino-Komuro pistol (sometimes spelled Komura) was developed by a young Japanese inventor named Kumazo Hino, and financed by Tomijiro Komuro in the first decade of the 20th century. The gun uses a virtually unique blow-forward mechanism, which makes it very interesting to study. The rear of the receiver houses a fixed firing pin, and the barrel is pushed forward upon firing. To cock the gun, the barrel is manually pulled forward about one inch (using serrations on the exposed front section of the barrel). As the barrel is pulled forward, it pulls with it a follower that pulls a cartridge forward out of the magazine and lifts it up into the axis of the bore. When the grip safety and trigger are depressed, the barrel is snapped backwards into the action by a spring. The ready cartridge is chambered and driven backwards with the barrel onto the fixed firing pin.

(more…)

August 20, 2023

1908 Japanese Hino Komura Pistol

August 18, 2023

Did Hitler Cancel the Sturmgewehr?

Forgotten Weapons

Published 10 May 2023It is often said that Hitler personally cancelled the Sturmgewehr development … could that really be true?

Yes! He actually nixed the program three separate times, and the German Army General Staff continued the project behind his back. They knew the rifle was what the Wehrmacht desperately needed if it was to have any hope of victory in the East, and they were determined to bring it to fruition. He did ultimately relent, and approved it to replace the Mauser K98k in early 1944 — but by that time a great deal of opportunity had been lost. Today we will delve into the details of just how the program developed as it pertains to his approval …

(more…)

August 17, 2023

“… the Chinese invented gunpowder and had it for six hundred years, but couldn’t see its military applications and only used it for fireworks”

John Psmith would like to debunk the claim in the headline here:

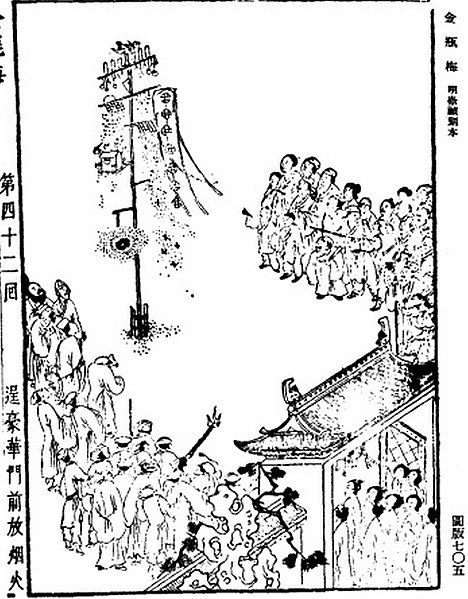

An illustration of a fireworks display from the 1628-1643 edition of the Ming dynasty book Jin Ping Mei (1628-1643 edition).

Reproduced in Joseph Needham (1986). Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 5: Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7: Military Technology: The Gunpowder Epic. Cambridge University Press. Page 142.

There’s an old trope that the Chinese invented gunpowder and had it for six hundred years, but couldn’t see its military applications and only used it for fireworks. I still see this claim made all over the place, which surprises me because it’s more than just wrong, it’s implausible to anybody with any understanding of human nature.

Long before the discovery of gunpowder, the ancient Chinese were adept at the production of toxic smoke for insecticidal, fumigation, and military purposes. Siege engines containing vast pumps and furnaces for smoking out defenders are well attested as early as the 4th century. These preparations often contained lime or arsenic to make them extra nasty, and there’s a good chance that frequent use of the latter substance was what enabled early recognition of the properties of saltpetre, since arsenic can heighten the incendiary effects of potassium nitrate.

By the 9th century, there are Taoist alchemical manuals warning not to combine charcoal, saltpetre, and sulphur, especially in the presence of arsenic. Nevertheless the temptation to burn the stuff was high — saltpetre is effective as a flux in smelting, and can liberate nitric acid, which was of extreme importance to sages pursuing the secret of longevity by dissolving diamonds, religious charms, and body parts into potions. Yes, the quest for the elixir of life brought about the powder that deals death.

And so the Chinese invented gunpowder, and then things immediately began moving very fast. In the early 10th century, we see it used in a primitive flame-thrower. By the year 1000, it’s incorporated into small grenades and into giant barrel bombs lobbed by trebuchets. By the middle of the 13th century, as the Song Dynasty was buckling under the Mongol onslaught, Chinese engineers had figured out that raising the nitrate content of a gunpowder mixture resulted in a much greater explosive effect. Shortly thereafter you begin seeing accounts of truly destructive explosions that bring down city walls or flatten buildings. All of this still at least a hundred years before the first mention of gunpowder in Europe.

Meanwhile, they had also been developing guns. Way back in the 950s (when the gunpowder formula was much weaker, and produced deflagarative sparks and flames rather than true explosions), people had already thought to mount containers of gunpowder onto the ends of spears and shove them in peoples’ faces. This invention was called the “fire lance”, and it was quickly refined and improved into a single-use, hand-held flamethrower that stuck around until the early 20th century.1 But some other inventive Chinese took the fire lances and made them much bigger, stuck them on tripods, and eventually started filling their mouths with bits of iron, broken pottery, glass, and other shrapnel. This happened right around when the formula for gunpowder was getting less deflagarative and more explosive, and pretty soon somebody put the two together and the cannon was born.

All told it’s about three and a half centuries from the first sage singing his eyebrows, to guns and cannons dominating the battlefield.2 Along the way what we see is not a gaggle of childlike orientals marvelling over fireworks and unable to conceive of military applications. We also don’t see an omnipotent despotism resisting technological change, or a hidebound bureaucracy maintaining an engineered stagnation. No, what we see is pretty much the opposite of these Western stereotypes of ancient Chinese society. We see a thriving ecosystem of opportunistic inventors and tacticians, striving to outcompete each other and producing a steady pace of technological change far beyond what Medieval Europe could accomplish.

Yet despite all of that, when in 1841 the iron-sided HMS Nemesis sailed into the First Opium War, the Chinese were utterly outclassed. For most of human history, the civilization cradled by the Yellow and the Yangtze was the most advanced on earth, but then in a period of just a century or two it was totally eclipsed by the upstart Europeans. This is the central paradox of the history of Chinese science and technology. So … why did it happen?

1. Needham says he heard of one used by pirates in the South China Sea in the 1920s to set rigging alight on the ships that they boarded.

2. I’ve left out a ton of weird gunpowder-based weaponry and evolutionary dead ends that happened along the way, but Needham’s book does a great job of covering them.

August 11, 2023

The Weirdest Boats on the Great Lakes

Railroad Street

Published 5 May 2023Whalebacks were a type of ship indigenous to the Great Lakes during the late 1890s and mid 1900s. They were invented by Captain Alexander McDougall, and revolutionized the way boats on the Great Lakes handled bulk commodities. Unfortunately, their unique design was one of the many factors which led to their discontinuation.

(more…)

August 2, 2023

You say you want a revolution …

The latest book review from the Psmiths is Bernard Yack’s The Longing for Total Revolution: Philosophic Sources of Social Discontent from Rousseau to Marx and Nietzsche, by John Psmith:

This is a book by Bernard Yack. Who is Bernard Yack? Yack is fun, because for a mild-mannered liberal Canadian political theorist he’s dropped some dank truth-bombs over the years. For example, check out his short and punchy 2001 journal article “Popular Sovereignty and Nationalism” if you need a passive-aggressive gift for the democratic peace theorist in your life.1 The subject of that essay is unrelated to the subject of the book I’m reviewing, but the approach, the method, and the vibe are similar. The general Yack formula is to take some big trendy topic (like “nationalism”) and examine its deep philosophical and intellectual substructure while totally refusing to consider material conditions. He’s kind of like the anti-Marx — in Yack’s world not only do ideas have consequences, they’re about the only things that do. Even when this is unconvincing, it’s usually very interesting.

The topic of this book is radicalism in the ur-sense of “a desire to get to the root”. What Yack finds interesting about radicalism is that it’s so new. It’s a surprising fact that the entire idea of having a revolution, of burning down society and starting again with radically different institutions, was seemingly unthinkable until a certain point in history. It’s like nobody on planet Earth had the idea, and then suddenly sometime in the 17th or 18th century a switch flips and it’s all anybody is talking about. We’re used to that sort of pattern for scientific discoveries, or for very original ways of thinking about the universe, but “let’s destroy all of this and try again” isn’t an incredibly complex or sophisticated thought, so why did it take so many millennia for somebody to have it?

Well, first of all, is this claim even true? One thing you do see a lot of in premodern history is peasant rebellions, but dig a little deeper into any of them and the first thing you notice is that (sorry vulgar Marxists)2 there’s nothing especially “revolutionary” in any of these conflagrations. The most common cause of rebellion is some particular outrage, and the goal of the rebellion is generally the amelioration of that outrage, not the wholesale reordering of society as such. The next most common cause of rebellions is a bandit leader who is some variety of total psycho and gets really out of control. But again, prior to the dawn of the modern era, these psychos led movements that were remarkably undertheorized. The goal was sometimes for the psycho to become the new king, sometimes the extinguishment of all life on earth, but you hardly ever saw a manifesto demanding the end of kings as such. Again, this is weird, right? Is it really such a difficult conceptual leap to make?

Peasant rebellions are demotic movements, but modern revolutions are usually led by frustrated intellectuals and other surplus elites. When elites did get involved in pre-modern rebellions, their goals were still fairly narrow, like those of the peasants — sometimes they wanted to slightly weaken the power of the king, other times they wanted to replace the king with his cousin. But again this is just totally different in kind from the 18th century onwards, when intellectuals and nobles are spending practically all of their time sitting around in salons and cafés, debating whose plan for the total overhaul of society, morality, and economic relations is best.

The closest you get to this sort of thing is the tradition of Utopian literature, from Plato’s Republic to Thomas More, but what’s striking about this stuff is how much ironic distance it carried — nobody ever plotted terrorism to put Plato’s or More’s theories into practice. Nobody ever got really angry or excited about it. But skip forward to the radical theorizing of a Rousseau or a Marx or a Bakunin, and suddenly people are making plans to bomb schools because it might bring the Revolution five minutes closer. So what changed?

Well this is a Bernard Yack book, so the answer definitely isn’t the printing press. It also isn’t secularization, the Black Death, urbanization, the Reformation, the rise of industrial capitalism, the demographic transition, or any of the dozens of other massive material changes that various people have conjectured as the cause of radical political ferment. Instead Yack points to two abstract philosophical premises: the first is a belief in the possibility of “dehumanization”, the idea that one can be a human being and yet be living a less than human life. The second is “historicism” in the sense of a belief that different historical eras have fundamentally different modes of social interaction.

Both views had some historical precedent (for instance historicism is clearly evident in the writings of Machiavelli and Montesquieu), but it’s their combination that’s particularly explosive, and Rousseau is the first person to place the two elements together and thereby assemble a bomb. Because for Rousseau, unlike for any of the ancient or medieval philosophers, merely to be a member of the human species does not automatically mean you’re living a fully-human life. But if humanity is something you can grow into, then it’s also something that you can be prevented from growing into. Thus: “that I am not a better person becomes for Rousseau a grievance against the political order. Modern institutions have deformed me. They have made me the weak and miserable creature that I am.”

But what if the qualities of social interaction which have this dehumanizing effect are inextricably bound up with the dominant spirit of the age? In that case, it might be impossible to really live, impossible to produce happy and well-adjusted human beings, without a total overhaul of society and all of its institutions. This also clarifies how the longing for total revolution is distinct from utopianism — utopian literature is motivated by a vision of a better or more just order. Revolutionary longing springs from a hatred of existing institutions and what they’ve done to us. This is an important difference, because hate is a much more powerful motivator than hope. In fact Yack goes so far as to say (in a wonderfully dark passage) that the key action of philosophers and intellectuals upon history is the invention of new things to hate. Can you believe this guy is Canadian?

1. Of course, if my reading of MITI and the Japanese Miracle is correct, popular sovereignty may not be around for that much longer.

2. I say “vulgar” Marxists, because for the sophisticated Marxists (including Marx himself) it’s already pretty much dogma that premodern rebellions by immiserated peasants aren’t “revolutionary” in the way they care about.

How Shipping Containers Took Over the World (then broke it)

Calum

Published 5 Oct 2022The humble shipping container changed our society — it made International shipping cheaper, economies larger and the world much, much smaller. But what did the shipping container replace, how did it take over shipping and where has our dependance on these simple metal boxes led us?

(more…)

July 31, 2023

RSC 1917: France’s WW1 Semiauto Rifle

Forgotten Weapons

Published 17 Nov 2015Did you know that the French Army issued more than 80,000 semiautomatic rifles during WWI? They had been experimenting with a great many semiauto designs before the war, and in 1916 finalized a design for a rotating bolt, long stroke gas piston rifle (with more than few similarities to the M1 Garand, actually) which would see field service beginning in 1917. An improved version was put into production in 1918, but too late to see any significant combat use.

The RSC 1917 was not a perfect design, but it was good enough and the only true semiauto infantry rifle fielded by anyone in significant numbers during the war.

July 29, 2023

French 75mm of 1897

vbbsmyt

Published 30 Dec 2021The French 75 is widely regarded as the first modern artillery piece. It was the first field gun to include a hydro-pneumatic recoil mechanism, which kept the gun’s trail and wheels perfectly still during the firing sequence. Since it did not need to be re-aimed after each shot, the crew could reload and fire as soon as the barrel returned to its resting position. In typical use the French 75 could deliver fifteen rounds per minute on its target, either shrapnel or high-explosive, up to about 8,500 m (5.3 mi) away. Its firing rate could even reach close to 30 rounds per minute, albeit only for a very short time and with a highly experienced crew. [wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canon_d…]

The concept for the gun anticipated future conflict being a war of manoeuver — with massed infantry and cavalry attacks — based on the experience of the wars of 1870-1872. Consequently the gun was designed to be able to be moved easily, set up quickly and fire antipersonnel shells (shrapnel) rapidly, and without the need to reset the carriage after each shot. Two critical components were the cased ammunition (shell and cartridge as a single unit) and a recoil system that completely absorbed the recoil forces and returned the gun to its original position without disturbing the gun’s position.

This animation shows the actions necessary to prepare the gun from its “travelling” state to operational state. The carriage has to be “locked” into a fixed position and levelled. The operation of shrapnel shells depends upon setting a time fuse to explode the shell just in front of an attacking force, to shower them with balls, and demonstrates the French Débouchoir mechanical fuse setter that allowed time fuses to be set rapidly and accurately. The liquid (oil) and air (pneumatic) recoil mechanism used a “floating piston” — on one side hydraulic oil and on the other compressed air. The design must keep these two separated while allowing the free piston to move rapidly. The French design laid great emphasis on seals made of silver – being soft enough to conform to the sleeve housing, but as reported by the US when they started manufacturing the 75mm, the key element was highly precise machining of the sleeve housing the free piston.

The French 75mm of 1897 was of less use with the introduction of trench warfare, where howitzers and mortars being the primary artillery, but the 75mm retained some value, one use being firing shrapnel shells at aircraft. A longer time fuse had to be developed to reach the altitude that some aircraft flew at.

(more…)

July 24, 2023

Lorenzoni Repeating Flintlock Pistol

Forgotten Weapons

Published 13 Aug 2012Today we have one of the oldest guns we’ve looked at, a Lorenzoni repeating flintlock pistol. The system was designed by an Italian gunmaker in Florence name Michele Lorenzoni. They were made in very small numbers, and the workmanship is stunning, especially considering that they were first manufactured in the 1680s.

Instead of using a revolving cylinder pre-loaded with multiple shots, the Lorenzoni system utilizes powder and ball magazines in the frame of the gun and a rotating breechblock much like a powder throw tool used today for reloading ammunition.

(more…)

July 23, 2023

Tom Whipple’s history of radar development during WW2

In The Critic, Robert Hutton reviews The Battle of the Beams by historian Tom Whipple, who retells the story of the technological struggle between Britain and Germany during the Second World War to find ways to guide RAF or Luftwaffe pilots to their targets:

In an age when my phone can tell me exactly where I am and how to get where I’m going, it’s hard sometimes to imagine a time when navigation was one of any traveller’s great challenges. At the outbreak of the Second World War, the advice to Royal Air Force pilots trying to find their way was, more or less, to look out of the window and see whether anything on the ground looked familiar. The Luftwaffe, though, had a rather more sophisticated means of finding their targets.

As Britain braced herself for the bomber onslaught of 1940, there was comfort in knowing that radar would give Hurricanes and Spitfires advance warning of where the attack was coming. As soon as the sun went down, so did the fighters: at night, relying on their eyeballs, they simply couldn’t find the enemy.

That wasn’t so bad, as long as the German pilots had the same problem, but one young British scientist began to suspect that the Luftwaffe had developed a technology that allowed them to find their way even in the dark, guided by radio beams. In June 1940 he found himself explaining to Winston Churchill that German bombers could accurately reach any spot over England that they wanted, even in darkness.

Reg “RV” Jones was the original boffin: a gifted physicist who was recruited to the Air Ministry at the start of the war to help make sense of intelligence reports that offered clues about enemy technology. It was a role to which he was perfectly suited: a man who liked puzzles, with the ability to absorb lots of information and see links, as well as the arrogance to insist on his conclusions, even when his superiors didn’t like them.

The story of the radio battle has been told before, not least by Jones himself. His 1978 memoir Most Secret War was a bestseller and remains in print. It is 700 pages long, though, and it assumes a lot of knowledge about the way 1940s radios worked that readers probably had 50 years ago. Since few people under 50 have much clue why a radio would need a valve or what you might do with a slide rule, there is definitely room for a fresh telling.

July 20, 2023

Three phases of a cultural cycle

Chris Bray visits an art museum and shares some thoughts provoked by his experiences:

There’s a moment, in a museum supported by a deep permanent collection, when you transition from glowing oil paint depictions of Lord Major Fluffington P. Farnsworth-Hadenwallace, Seventh Earl of Wherever, Ninth Duke of Someotherplace, posing in his lordly estate with a bowl of fruit and his array of status decorations, to the shocking emergence of late-19th century innovations in painting, and you find yourself thinking that huh, this Renoir dude really knew his stuff, like you’re the first person to ever notice.

These explosive moments of creativity were usually social: artists gathering, talking, seeing the work of other artists and thinking about new ways of seeing and showing. Individual acts of artistic liberation appeared in the context of an emerging cultural freedom. Renoir and Monet hung out together.

You can see the tide coming in and going out. You can watch enormous waves of joyful innovation, or — respectful nod to the German Expressionists — anxious and anguished innovation. It’s on the wall: here’s the moment when people experienced unusual freedom of vision. You can see artists pursuing beauty with disciplined attention, in a cultural atmosphere that allows the pursuit.

And it’s just so abundantly clear that something opened in the world, somewhere between 1870 and … 1950? Or so? And then it began to close, and the closure recently began picking up force. There are periods of general creativity and periods of general stultification and retrenchment; there was one Italian Renaissance, one Scottish Enlightenment, and so on. Weimar Germany, sick as it was, fired more brilliant art into the world in twenty years than many cultures produce in a period of centuries, though a certain teenager who lives in my house would like you to know that Fritz Lang sucks and please stop with those boring movies and I’ll be in my room.

So it seems to me that the first part of the cultural cycle is the making phase, the period of astonishing innovation; then comes the consolidation and appreciation, the moment the heirs to sewing machine fortunes show up and notice how good everything is; then comes the phase when a few monk-equivalents try to keep the record of accomplishment alive in the context of a hostile or indifferent culture, while most institutions reject innovation and turn to scolding, wrecking, and cannibalization. The fifth Indiana Jones movie. She-Hulk. Like that. I just spent twenty minutes in a Barnes and Noble, and the “new fiction” section may still be making me feel tired next week.

We’re living through a decline in fertility — in literal fertility, in rates of people being married and making babies and hanging around to raise children — at the moment when cultural fertility also seems to be going into freefall. Your results may vary, but I’m finding the moment manageable, largely with piles of earlier books and the occasional sprint to a place like the Clark. Fecundity and sterility appear in cycles, but you can time travel. You can reach back. Mary McCarthy got me through June, and Willa Cather is helping with July. Evelyn Waugh covered roughly February through May.

If you’re near the Berkshires, a worthwhile Edvard Munch exhibit is around until mid-October.

It’s very strange to be in the river and then to suddenly notice that it isn’t running — you’ve hit a long stretch of dead water, so still it starts to stink. I assume it will pass. But until then …

July 14, 2023

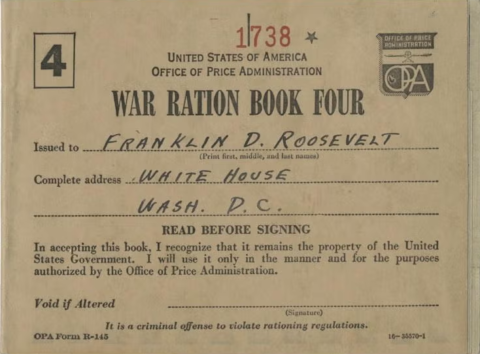

Bread rationing in the United States during WW2

I haven’t studied the numbers, but I strongly suspect that most US government food rationing during the war was effectively theatre to encourage more support of the war effort: except in a very few areas, the US was more than self-sufficient in most foodstuffs. At the Foundation for Economic Education, Lawrence W. Reed recounts one of the least effective government moves in food rationing:

According to an old joke from the socialist and frequently underfed Soviet Union, Stalin goes to a local wheat farm to see how things are going. “We have so many bags of wheat that, if piled on top of each other, they could reach God himself!” the farmer told Comrade Stalin.

“But God does not exist,” the dictator angrily replied. “Exactly!” said the farmer. “And neither does the wheat.” Nobody knows what happened to the farmer, but at least Stalin died in 1953.

Soviet socialism, with its forced collectivism and ubiquitous bread lines, gave wheat a bad name. Indeed, it was lousy at agriculture in general. As journalist Hedrick Smith (author of The Russians) and many other authorities noted at the time, small privately owned plots comprised just three percent of the land but produced anywhere from a quarter to a half of all produce. Collectivized agriculture was a joke.

America is not joke-free when it comes to wheat. We are a country in which sliced bread was both invented and banned, and a country in which growing wheat for your own consumption was ruled to be an act of “interstate commerce” that distant bureaucrats could regulate. No kidding.

On this anniversary — July 7 — of both the birth in 1880 of sliced bread’s inventor and of the day in 1928 that the first sliced bread from his machine was sold, it’s fitting to recall these long-forgotten historical facts.

The Iowa-born jeweler and inventor Otto Rohwedder turned 48 on the very day the first consumer bought the product of his new slicing machine. The bread was advertised as “the greatest forward step in the baking industry since bread was wrapped” and it quickly gave rise to the popular phrase, “the greatest thing since sliced bread.” Before 1928, American housewives cut many a finger by having to slice off every piece of bread from the loaves they baked or bought. Sliced bread was an instant sensation.

Rohwedder earned seven patents for his invention. The original is proudly displayed at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. He likely made a lot more money from the bread slicing machine than he ever did as a jeweler. He died in 1960 at the age of 80.

Enter Claude Wickard, Secretary of Agriculture under Franklin Roosevelt from 1940 to 1945. On January 18, 1943, he banned the sale of sliced bread. Exactly why seems to be in dispute but the most likely rationale was to save wax paper and other resources for war production. He rescinded the ban two months later, explaining then that “the savings are not as much as we expected.”

I’m sure Hitler and Hirohito were relieved.

July 12, 2023

Nazi drone war begins – War Against Humanity 103

World War Two

Published 11 Jul 2023Bombing enemy civilians does nothing to advance a nation’s war effort. But now, Adolf Hitler believes that the V-1 flying bomb, the first of the Vengeance Weapons, will bring London to its knees and unite the German population behind the war effort as never before. The missiles are ready for launch and thousands more civilians will die to satisfy the Führer’s

delusions.

(more…)

July 10, 2023

QotD: Liberal and conservative views on innovation

Liberals and conservatives don’t just vote for different parties — they are different kinds of people. They differ psychologically in ways that are consistent across geography and culture. For example, liberals measure higher on traits like “openness to new experience” and seek out novelty. Conservatives prefer order and predictability. Their attachment to the status quo is an impediment to the re-ordering of society around new technology. Meanwhile, the technologists of Silicon Valley, while suspicious of government regulation, are still some of the most liberal people in the country. Not all liberals are techno-optimists, but virtually all techno-optimists are liberals.

A debate on the merits of change between these two psychological profiles helps guarantee that change benefits society instead of ruining it. Conservatives act as gatekeepers enforcing quality control on the ideas of progressives, ultimately letting in the good ones (like democracy) and keeping out the bad ones (like Marxism). Conservatives have often been wrong in their opposition to good ideas, but the need to win over a critical mass of them ensures that only the best-supported changes are implemented. Curiously, when the change in question is technological rather than social, this debate process is neutered. Instead, we get “inevitablism” — the insistence that opposition to technological change is illegitimate because it will happen regardless of what we want, as if we were captives of history instead of its shapers.

This attitude is all the more bizarre because it hasn’t always been true. When nuclear technology threatened Armageddon, we did what was necessary to limit it to the best of our ability. It may be that AI or automation causes social Armageddon. No one really knows — but if the pessimists are right, will we still have it in us to respond accordingly? It seems like the command of the optimists to lay back and “trust our history” has the upper hand.

Conservative critics of change have often been comically wrong — just like optimists. That’s ultimately not so interesting, because humans can’t predict the future. More interesting have been the times when the predictions of the critics actually came true. The Luddites were skilled artisans who feared that industrial technology would destroy their way of life and replace their high-status craft with factory drudgery. They were right. Twentieth century moralists feared that the automobile would facilitate dating and casual sex. They were right. They erred not in their predictions, but in their belief that the predicted effects were incompatible with a good society. That requires us to have a debate on the merits — about the meaning of the good life.

Nicholas Phillips, “The Fallacy of Techno-Optimism”, Quillette, 2019-06-06.

June 29, 2023

Miller’s Musket Conversion: The Trapdoor We Have At Home

Forgotten Weapons

Published 15 Mar 2023In 1865, brothers William and George Miller of Meriden CT patented a system to convert percussion muskets to use the new rimfire ammunition that was becoming available. Between 1865 and 1867, the local Meridan Manufacturing Company converted 2,000 surplus US Model 1861 muskets (mostly made by Parker & Snow) to the Miller system, using .58 rimfire ammunition. The US military tested one of these conversions in 1867, and found it to suffer from some gas leakage and about a 3% misfire rate. There was no further Army interest, although the New York and Maryland state militias did both purchase small numbers of the guns.

(more…)