I should be clear I am making this term up (at least as far as I know) to make a contrast between what Total War has, which are single units made up of soldiers with identical equipment loadouts that have a dual function (hybrid infantry) and what it doesn’t have: units composed of two or more different kinds of infantry working in concert as part of a single unit, which I am going to call composite infantry.

This is actually a very old concept. The Neo-Assyrian Empire (911-609 BC) is one of the earliest states where we have pretty good evidence for how their infantry functioned – there was of course infantry earlier than this, but Bronze Age royal records from Egypt, Mesopotamia or Anatolia tend to focus on the role of elites who, by the late Bronze Age, are increasingly on chariots. But for the early Iron Age Neo-Assyrian empire, the fearsome effectiveness of its regular (probably professional) infantry, especially in sieges, was a key component of its foreign-policy-by-intimidation strategy, so we see a lot more of them.

That infantry was split between archers and spear-and-shield troops, called alternately spearmen (nas asmare) or shield-bearers (sab ariti). In Assyrian artwork, they are almost always shown in matched pairs, each spearman paired off with a single archer, physically shielding the archer from attack while the archer shoots. The spearmen are shown with one-handed thrusting spears (of a fairly typical design: iron blade, around 7 feet long) and a shield, either a smaller round shield or a larger “tower” shield. Assyrian records, meanwhile, reinforce the sense that these troops were paired off, since the number of archers and spearmen typically match perfectly (although the spearmen might have subtypes, particularly the “Qurreans” who may have been a specialist type of spearman recruited from a particular ethnic group; where the Qurreans show up, if you add Qurrean spearmen to Assyrian spearmen, you get the number of archers). From the artwork, these troops seem to have generally worked together, probably lined up in lines (in some cases perhaps several pairs deep).

The tactical value of this kind of composite formation is obvious: the archers can develop fire, while the spearmen provide moving cover (in the form of their shields) and protection against sudden enemy attack by chariot or cavalry with their spears. The formation could also engage in shock combat when necessary; the archers were at least sometimes armored and carried swords for use in close combat and of course could benefit (at least initially) from the shields of the front rank of spearmen.

The result was self-shielding shock-capable foot archer formations. Total War: Warhammer also flirts with this idea with foot archers who have their own shields, but often simply adopts the nonsense solution of having those archers carry their shields on their backs and still gain the benefit of their protection when firing, which is not how shields work (somewhat better are the handful of units that use their shields as a firing rest for crossbows, akin to a medieval pavisse).

We see a more complex version of this kind of composite infantry organization in the armies of the Warring States (476-221 BC) and Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) periods in China. Chinese infantry in this period used a mix of weapons, chiefly swords (used with shields), crossbows and a polearm, the ji which had both a long spearpoint but also a hook and a striking blade. In Total War: Three Kingdoms, which represents the late Han military, these troop-types are represented in distinct units: you have a regiment of ji-polearm armed troops, or a regiment of sword-and-shield troops, or a regiment of crossbowmen, which maneuver separately. So you can have a block of polearms or a block of crossbowmen, but you cannot have a mixed formation of both.

Except that there is a significant amount of evidence suggesting that this is exactly how the armies of the Han Dynasty used these troops! What seems to have been common is that infantry were organized into five-man squads with different weapon-types, which would shift their position based on the enemy’s proximity. So against a cavalry or chariot charge, the ji might take the front rank with heavier crossbows in support, while the sword-armed infantry moved to the back (getting them out of the way of the crossbows while still providing mass to the formation). Of course against infantry or arrow attack, the swordsmen might be moved forward, or the crossbowmen or so on (sometimes there were also spearmen or archers in these squads as well). These squads could then be lined up next to each other to make a larger infantry formation, presenting a solid line to the enemy.

(For more on both of these military systems – as well as more specialist bibliography on them – see Lee, Waging War (2016), 89-99, 137-141.)

Bret Devereaux, “Collection: Total War‘s Missing Infantry-Type”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-04-01.

January 11, 2025

QotD: “Composite” pre-gunpowder infantry units

December 13, 2024

Modern (western) armies never seem to have enough infantry, no matter how high-tech the battlefield gets

Over the last century, one of the apparent constants in military doctrine has been that the latest and greatest technical innovation has somehow eclipsed the importance of boring old infantry units. Tanks were the future! No, tactical airpower was the future! No, nuclear weapons were the future! No, airmobile and helicopter units were the future! No, drones are the future! Yet every time the guns started firing, the limiting factor always seemed to be “not enough infantry” (at least among western militaries). You definitely needed more specialist and support units to handle the latest whizzy toys being deployed, yet it was still the infantry who mattered in the end. That’s just me noodling … it’s only loosely related to the rest of the post.

In my weekly recommendations list from Substack, they included this post from Bazaar of War which discusses the changes in organization of tactical and operation level units over time to best meet the needs of the modern battlefield:

Command post for a single battalion-sized element in a brigade combat team.

Photo by Sgt Anita Stratton, US Army.

Modern ground forces are torn between two competing demands, for infantry and for enablers. Urban operations and large-scale combat over the past decade demonstrate that infantry remains just as essential as ever. Yet that same infantry needs a lot of low-level support just to survive and remain effective: drone operators, EW, and engineers, not to mention armor and artillery. This poses an obvious dilemma for force management—not least when faced with competing demands for air, naval, and missile assets—but also raises questions about force structure.

Organizing the Force

One of the key decisions in how future wars will be fought is what will be the primary tactical unit. Inevitably, certain command levels are much more important than others: those which require greater freedom from higher headquarters than they allow their own subordinates. This partly comes down to a question of where the combined-arms fight is best coordinated, which in turn depends heavily on technology.

This has varied a lot over time. The main tactical formation of the Napoleonic army was the corps, which had organic artillery, cavalry, and engineers that allowed it to fight independent actions with a versatility not available to smaller units. The Western Front of World War II was a war of divisions at the tactical level and armies at the operational, a pattern which continued through the Cold War. The US Army shifted to a brigade model during the GWOT era, on the assumption that future deployments would be smaller scale and lower intensity; only recently has it made the decision to return to a divisional model. Russia also switched to a brigade model around this time, although more for cost and manpower reasons.

Tweaking the Hierarchy

At the same time, certain echelons have disappeared altogether. The subdivisions of Western armies reached their greatest extent in World War I, as new ones were added at the extremities of the model standardized during the French Revolution: fireteams/squads to execute trench raids, army groups to manage large sections of the front. At the same time, cuts were made around the middle. Machine guns were pushed from the regimental level down to battalions over the course of the war, reducing the number of these bulkier regiments in a division; this accordingly eliminated the need for brigades as a tactical unit.

This continued with the next major war. More organic supporting arms and increased mobility made combat more dispersed, creating the need for supply, communications, intelligence, and medical support at lower levels. As units at each echelon grew fatter, it became too cumbersome to have six separate headquarters from battalion to field army. Midway through World War II, the Soviets followed the Western example of eliminating brigades, and got rid of corps to boot (excepting ad-hoc and specialized formations). During the Cold War, the increasing use of combined arms at a lower level caused most NATO militaries to eliminate the regiment/brigade distinction altogether: the majority favored the larger brigade, which could receive supporting units to fight as a brigade combat team, although the US Marines retained regiments as brigades in all but name (the French, by contrast, got rid of most of their battalions, preferring regiments formed of many companies).

November 20, 2024

The Korean War Week 22 – Winter is Coming! – November 19, 1950

The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published 19 Nov 2024Eighth Army commander Walton Walker makes his final preparations for the big push north to the Yalu River. The Communist Chinese prepare their own forces and wait for the Americans to make their move. At the same time, the freezing Korean winter arrives in force, plunging temperatures well below freezing. The Americans must get this done, and soon.

(more…)

November 6, 2024

The Korean War 020 – American Disaster at Unsan! – November 5, 1950

The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published 5 Nov 2024American forces drive onwards, almost oblivious to the emerging Communist Chinese threat. At Unsan, an American regiment finds itself at the mercy of two Chinese divisions, who bear down on it from three sides. Getting out before being overrun will be no easy feat.

Chapters

01:18 Destruction of the 7th

03:41 Unsan Prelude

05:41 The Disaster at Unsan

10:47 Aftermath

13:31 Elsewhere

16:15 Summary

16:30 Conclusion

(more…)

October 16, 2024

Roman Historian Rates 10 Ancient Rome Battles In Movies And TV | How Real Is It? | Insider

Insider

Published Jun 18, 2024Historian Michael Taylor rates depictions of ancient Rome in Gladiator, Spartacus, and Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny.

(more…)

October 13, 2024

The Deadliest Day of the British Army: The Battle of the Somme

The Great War

Published Jun 14, 2024The Battle of the Somme was one of the bloodiest of the First World War. From July to November 1916, millions of men struggled to fight in mud, under crushing shellfire, or in a hail of machine gun bullets. The Somme has been a synonym for the futility of trench warfare, but also the subject of fierce debate – who really won the Battle of the Somme?

(more…)

September 23, 2024

Forgotten War Ep3 – Death in the Arakan

HardThrasher

Published 18 Sept 2024Please consider donations of any size to the Burma Star Memorial Fund who aim to ensure remembrance of those who fought with, in and against 14th Army 1941–1945 — https://burmastarmemorial.org/

(more…)

September 12, 2024

Infantry Combat: The Rifle Platoon by Col. John F. Antal

At anarchonomicon, kulak reviews Antal’s book from the 1990s:

There are a lot of weird experimental products in the world of Military Publishing … there’s no other subject for adults where professional volumes are published in the same format as children’s picture books where every other page is a full page image so that when you hold it in your hands you always have 50% picture/50% text, and yet that’s exactly how military atlases are formatted. They’re amazing!

Likewise military identification/vehicle guides, book length manuals or ship tours, or regimental campaign histories and memorabilia … These push the limits of the publishing medium, because they have to. The subject matter is complex, technical, tactile, risky, and multifaceted enough that aside from experimental horror novels or the vanishingly rare graphic novel … Nothing pushes the limits of paper so completely … indeed there are almost certainly some military history books that rival the experimental horror novel House of Leaves in terms of sheer medium breaking complexity.

And while Colonel John F. Antal hasn’t produced the most complex example of this… He may have produced one of the most experimental.

Infantry Combat: The Rifle Platoon is a simultaneous Military Tactics and Leadership crash course and semi-political argument about the wrong lessons that were learned from Operation Desert Storm (it was first published in 1995) in the format of a “Choose your own Adventure” novel.

And my god does it work. Its argument is incredibly well presented, its intangible concepts and ethos is really strongly conveyed, it teaches an impressive amount of theory and application despite NOT being a textbook of theory or doctrine …

And It just has no conceivable right to work as well as it works.

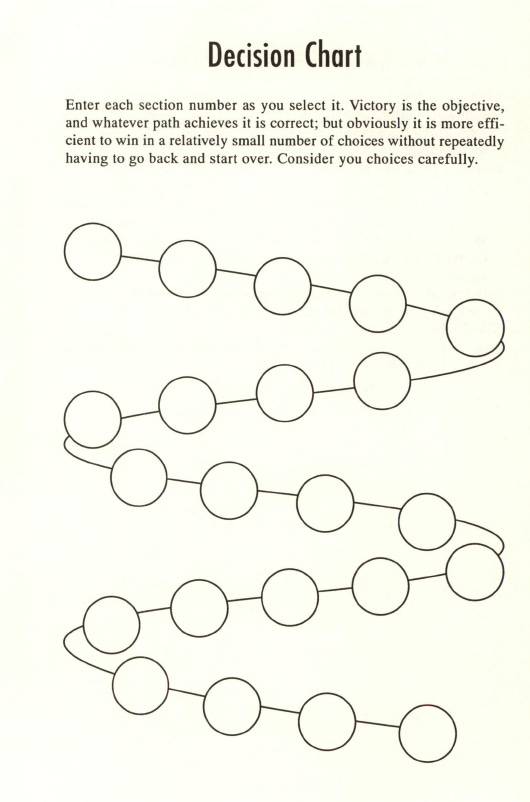

It actually does push the format of the “Choose your own adventure novel” incredibly far in terms of complexity. I’ve never seen one before that included several pages of charts just to track your decisions down the matrix.

The setup is primally simple.

You are US Army 2nd Lieutenant Davis. While it isn’t your first-First day, it is nearly your first after getting to the unit, and a very unlucky one at that.

You graduated West Point, attended ranger school, and this is day 2-3 of your first command.

America’s army is in an unnamed country and temporarily outnumbered as it is invaded, however they’re just dumb Arabs … its fine. Will probably get settled at the negotiating, and beside you have air dominance and the technological marvel of the US Military behind you.

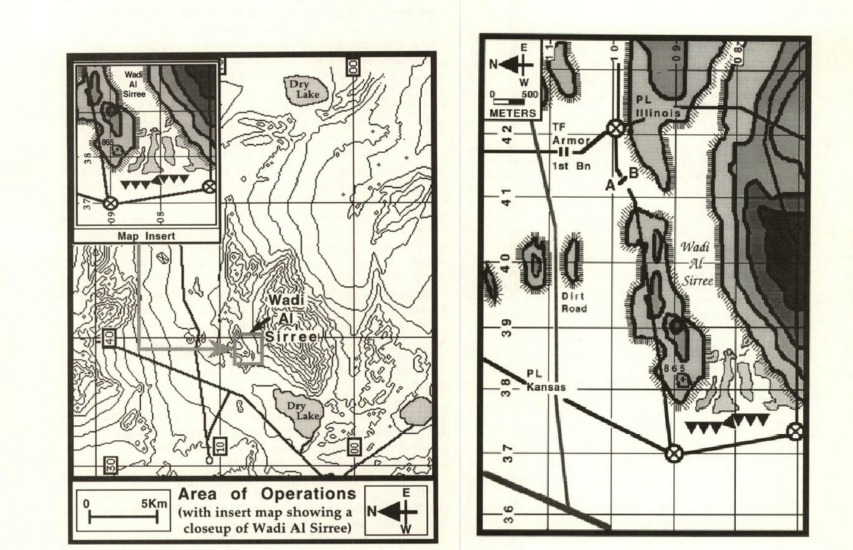

Note this map is oriented 90 degrees off. North is on the left, east at the top. The triangles are a tank ditch meant to stop armoured vehicles (like a massive dry moat)

The main force isn’t going to be attacking you.

Your lone platoon of just 38 will be defending Wadi Al Sirree, a narrow mountain pass separate and a little ahead of your main force.

You might think this is a little exposed but they’re almost certainly going to exploit the open country with their armor and proceed up the dirt road to hit the 1st armoured battalion and the rest of your company. This is the fastest way they can proceed and exploit their momentary numbers in the theater before the rest of the US military arrives. Your pass isn’t valuable much at all for a ground invasion, and besides there’s a massive tank ditch and other obstacles that will deter the enemy. Your troops are really just there as an auxiliary to the land and the ditch. Maybe spot some artillery fire.

But hey! This is a great opportunity to see what war in the late 20th/early 21st century is about up close and personal. Just keep your head down, let your NCOs who have the experience do their jobs, and you’ll get a nice combat medal on your second day on the job. Just try not to get in people’s way.

As you can guess, the job of a Infantry commander is probably a bit more complex than that …

PIAT: The weapon that could punch through steel but needed nerves to match

Forces News

Published Jun 3, 2024Tanks, soft-skin vehicles, bunkers and buildings — the PIAT could deal with them all.

The PIAT — Projector, Infantry, Anti-Tank — was a British weapon that proved its worth during the Normandy Landings.

It was introduced in 1943, first seeing action in Tunisia, but was used to good effect in France, and despite its name it was a true multi-purpose weapon.

(more…)

September 2, 2024

Roman auxiliaries – what was their role in the Imperial Roman army?

Adrian Goldsworthy. Historian and Novelist

Published May 8, 2024The non citizen soldiers of the Roman Auxilia served alongside the Roman citizens of the legions. In the second and third centuries AD, there were at least as many auxiliaries as there were legionaries — probably more. Some were cavalry or archers, so served in roles that complemented the close order infantry of the legions. Yet the majority were infantrymen, wearing helmet and body armour. They looked different from the legionaries, but was their tactical role and style of fighting also different. Today we look at the tactical role of Roman auxiliaries.

Extra reading:

I mention M. Bishop & J. Coulston, Roman Military Equipment which is one of the best starting places. Mike Bishop’s Osprey books on specific types of Roman army equipment are also excellent. Peter Connolly’s books, notably Greece and Rome at War, also remain well worthwhile.

August 31, 2024

Forgotten War Ep2 – You Walk, You Walk Or You Die Mate

HardThrasher

Published 30 Aug 2024Please consider donations of any size to the Burma Star Memorial Fund who aim to ensure remembrance of those who fought with, in and against 14th Army 1941–1945 – https://burmastarmemorial.org/

(more…)

August 30, 2024

QotD: The stalemate in the trenches, 1914-1918

Last time, we introduced the factors that created the trench stalemate in the First World War and we also laid out why the popular “easy answer” of simply going on the defensive and letting the enemy attack themselves to death was not only not a viable strategy in theory but in fact a strategy which had been tried and had, in the event, failed. But in discussing the problem the trench stalemate created on the Western Front, I made a larger claim: not merely that the problem wasn’t solved but that it was unsolvable, at least within the constraints of the time. This week we’re going to pick up that analysis to begin looking at other options which were candidates for breaking the trench stalemate, from new technologies and machines to new doctrines and tactics. Because it turns out that quite to the contrary of the (sometimes well-earned) dismal reputation of WWI generals as being incurious and uncreative, a great many possible solutions to the trench stalemate were tried. Let’s see how they fared.

Before that, it is worth recapping the core problem of the trench stalemate laid out last time. While the popular conception was that the main problem was machine-gun fire making trench assaults over open ground simply impossible, the actual dynamic was more complex. In particular, it was possible to create the conditions for a successful assault on enemy forward positions – often with a neutral or favorable casualty ratio – through the use of heavy artillery barrages. The trap this created, however, was that the barrages themselves tore up the terrain and infrastructure the army would need to bring up reinforcements to secure, expand and then exploit any initial success. Defenders responded to artillery with defense-in-depth, meaning that while a well-planned assault, preceded by a barrage, might overrun the forward positions, the main battle position was already placed further back and well-prepared to retake the lost ground in counter-attacks. It was simply impossible for the attacker to bring fresh troops (and move up his artillery) over the shattered, broken ground faster than the defender could do the same over intact railroad networks. The more artillery the attacker used to get the advantage in that first attack, the worse the ground his reserves had to move over became as a result of the shelling, but one couldn’t dispense with the barrage because without it, taking that first line was impossible and so the trap was sprung.

(I should note I am using “railroad networks” as a catch-all for a lot of different kinds of communications and logistics networks. The key technologies here are railroads, regular roads (which might speed along either leg infantry, horse-mobile troops and logistics, or trucks), and telegraph lines. That last element is important: the telegraph enabled instant, secure communications in war, an extremely valuable advantage, but required actual physical wires to work. Speed of communication was essential in order for an attack to be supported, so that command could know where reserves were needed or where artillery needed to go. Radio was also an option at this point, but it was very much a new technology and importantly not secure. Transmissions could be encoded (but often weren’t) and radios were expensive, finicky high technology. Telegraphs were older and more reliable technology, but of course after a barrage the attacker would need to be stringing new wire along behind them connecting back to their own telegraph systems in order to keep communications up. A counter-attack, supported by its own barrage, was bound to cut these lines strung over no man’s land, while of course the defender’s lines in their rear remained intact.)

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: No Man’s Land, Part II: Breaking the Stalemate”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-09-24.

August 10, 2024

“Heavy casualties” in a modern western army might count as “a skirmish” in earlier conflicts

I sent a link to Severian a few weeks ago, thinking it might be an interesting topic for his audience and he posted a response as part of Friday’s mailbag post. First, my explanation to him about why I thought the link was interesting:

I know that Edward Luttwak is what the Brits call “a Marmite figure” … people love or hate him and not much in between. I’ve read several of his books and found he had interesting things to say about the Roman and Byzantine armies in their respective eras but I haven’t found his modern analysis to be anywhere near as interesting. This time, however, he might well have found that acorn … is the dramatic casualty-aversion of western nations going to be a key element of future, shall we say “adventurism”?

Clearly, [Vladimir Putin and Benjamin Netanyahu] can still get their legions moving when they feel they need to, but could [insert current US President here] get the 101st Airborne into a high-casualty environment (let’s not pretend that Rishi Sunak or Keir Starmer could or would, and Macron’s posturing is nearly as bad as Baby Trudeau’s total lack of seriousness)?

Anyway, here’s the Marmite Man’s latest – https://unherd.com/2024/06/who-will-win-a-post-heroic-war

Sev responded:

US Army soldiers assigned to 2-7 Cavalry, 2nd Brigade Combat Team (BCT),3rd battalion 1st Division, rush a wounded Soldier from Apache Troop to a waiting USMC CH-46E Sea Knight helicopter during operation in Fallujah, Iraq, during Operation IRAQI FREEDOM.

Photo by SFC Johan Charles Van Boers via Wikimedia Commons.

I’ve often said that, from what I can tell — and bearing in mind my entire military experience consists of a .500 record at Risk! — AINO‘s entire force philosophy amounts to “zero casualties, ever”.

Note that this was true even in the 20th century, when America was still America. “Stupendous casualties” by American standards would hardly rate “a spot of bother” by Soviet. Wiki lists the bloodiest American battle as Eisenborn Ridge (part of the Bulge), with approximately five thousand fatalities.

A Soviet commander who didn’t come home with at least five thousand KIA could probably expect to be court-martialed for cowardice.

That same Wiki article separates “battles” from “campaigns” for some reason. There’s an entire “methodology” section I’m not going to wade into, but even looking at “campaigns”, the bloodiest (by their definitions) is Normandy — 29,204 KIA. That’s an entire campaign, which might rate “a hard week’s fighting” by Soviet, German, or Japanese standards.

Please understand, Americans’ unwillingness to take casualties was greatly to their credit. You want to know about “meat assaults”, ask the Germans, Russians, or Japanese (or the British or French in WWI). George Patton might not have been the best American commander, but he was the most American commander — the whole point of battle is to make the other stupid bastard die for his country. I am 100% in favor of minimal losses, for everyone, everywhere.

But “minimal” does not mean “none”. People die in wars. People die training for wars. People die in the vicinity of the training for war, because it’s inherently risky. It doesn’t make one some kind of monster to call these “acceptable” losses; it makes one a realist. One could just as easily say — and with the same justification — that a certain number of car crash fatalities, or iatrogenic deaths, etc. are acceptable losses, because there’s no way to have “interstate commerce” and “modern medicine”, respectively, without them.

The Fistagon seemingly denies this. Forget human losses for a moment, and consider mere equipment. You read up on, say, Air Force fighter planes, and you’re forced to conclude that their operations assume that all planes will be fully operational at all times. Again, saying nothing of the pilots, just the airframes. The Navy seems to assume that all ships everywhere will not only be serviceable, but actually in service, at all times. Just recently, they shot off all their ammo at Houthi and the Blowfish … and seemingly had no idea what to do, because as Milestone D walked us through it, it’s impossible to rearm while underway.

Think about that for a second. How the fuck is that supposed to work in a real war? Can we just put the war on pause for a few months, so all our ships can head back to port to reload?

In fact, I’d go so far as to speculate that that’s the origin of the phrase “meat assault”. What The Media are calling a “meat assault” is simply what was known to a sane age as “an assault”. No qualifiers. You know, your basic attack — go take that hill, and if you take the hill, and if enough of the attacking force survives to hold it, that’s a win. People who absolutely should know better, though, don’t see it that way.

Since we’re here … I remember having conversations with some folks in College Town re: the Battle of Fallujah, while it was happening (technically the Second Battle of Fallujah). Now, obviously quite a few of my interlocutors were ideologically committed to the position that this was senseless butchery. And in the fullness of time, I too have come around to the position that the entire Operation Endless Occupation was senseless butchery. But leaving all that aside, the point I was trying to make was a simple one: Total US casualties were 95 killed, 560 wounded.

Every one of them a senseless crime, I now believe, but considering Fallujah strictly as a military operation, that’s amazing. House-to-house fighting in a heavily urban area, against a fanatically committed opponent who was willing, indeed eager, to use every dirty trick in the book … and US forces took 655 total casualties. That’s about as well as it can possibly be done. The Red Army probably lost 655 men on the train ride getting to Stalingrad. I wouldn’t be surprised at all to learn that 655 is the daily casualty figure across the entire front in Ukraine … hell, I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that there are lots of individual sectors in Ukraine taking those kinds of daily losses. 655 is pretty damn good …

… but I was called every dirty name they could think of for suggesting it. I was called dirty names by people who called themselves conservatives, who were such ostentatious “patriots” that they’d embarrass Toby Keith.

Fallujah was fought in 2004, a time that seems like the Blessed Land of Sanity compared to now. AINO simply won’t take casualties. The Pentagram won’t — lose a tank, and you lose your job. (In battle, obviously. If you abandon it to the Taliban, no problem. And of course if you lose an entire war, it’s medals and promotions for everyone). And because the high command won’t, the field commanders won’t either. And because they won’t … well, “desertion” is an ugly word, but let’s just say Tim Walz won’t be the only guy who suddenly needs to be elsewhere right before it’s time to ship out. And as for the guys actually shanghaied into whatever foreign fuckup … well, “mutiny” is an even uglier word, but does anyone want to bet against it?

August 2, 2024

Why WW1 Turned Into Trench Warfare

The Great War

Published Apr 12, 2024Trench warfare is one of the lasting symbols of the First World War, especially on the Western Front. But when the war began, the German and French armies envisioned sweeping advances and defeating the enemy swiftly. So, how and why did the Western Front in 1914 turn into the trench system we associate with WW1?

(more…)

July 18, 2024

What is a Battle Rifle?

Forgotten Weapons

Published Apr 10, 2024“Battle rifle” is not a formally recognized term like “assault rifle”, but it is widely used, and I think it has a lot of utility. It is intended to differentiate between intermediate-caliber and full-power military rifles, and to that end I propose these four criteria to define a “battle rifle”:

1 – A military style or pattern rifle

2 – Intended primarily to be fired from the shoulder

3 – Self-loading (either semi- or fully automatic)

4 – Chambered for a full power rifle cartridge

(more…)