Biographics

Published 23 Mar 2020Check out Brilliant: https://brilliant.org/biographics

Check out Business Blaze: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCYY5…

This video is #sponsored by Brilliant.

TopTenz Properties

Our companion website for more: http://biographics.org

Our sister channel TopTenz: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCQ-h…

Our Newest Channel about Interesting Places: https://studio.youtube.com/channel/UC…Credits:

Host – Simon Whistler

Author – Morris M.

Producer – Jennifer Da Silva

Executive Producer – Shell HarrisBusiness inquiries to biographics.email@gmail.com

Source/Further reading:

Oxford National Dictionary of Biography: https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.109…

Interesting podcast on his life: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b04n…

Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/biography/…

History Today: https://www.historytoday.com/archive/…

The Thames Tunnel: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/histor…

The atmospheric railway: https://www.theguardian.com/science/t…

SS Great Britain accident: https://www.ssgreatbritain.org/about-…

August 31, 2021

Isambard Kingdom Brunel: The Genius of the Industrial Revolution

August 2, 2021

The World of the Franco-Prussian War – The 19th Century up to 1870 I GLORY & DEFEAT

realtimehistory

Published 30 Jun 2021Support Glory & Defeat: https://realtimehistory.net/gloryandd…

Welcome to the first primer episode for Glory & Defeat. In this first primer episode we will take a broad look at the industrial revolution and the emerging new ideologies of the 19th century: Communism and Nationalism.

» OUR PODCAST

https://realtimehistory.net/podcast – interviews with historians and background info for the show.» LITERATURE

Hobsbawm, Eric: The long nineteenth century. 3 Bände. London 1962-1987Kugler, Martin: “Fehleinschätzungen der Menschheit”, in: Die Presse v. 28.2.2010. o.S

Osterhammel, Jürgen: Die Verwandlung der Welt. Eine Geschichte des 19. Jahrhunderts. München 2009

Bruckmüller, Ernst et. al. (ed.): Putzger. Historischer Weltatlas. Berlin 2001

Staas, Christian: “Im Schatten der Schlote”, in: Geo Epoche Nr. 30. Die industrielle Revolution. 2008. S. 72-85

Bischoff, Jürgen: “Vorwärts durch Raum und Zeit”, in: Geo Epoche Nr. 30. Die industrielle Revolution. 2008. S. 56-71

» SOURCES

Engels, Friedrich: Die Lage der arbeitenden Klasse in England. Leipzig 1845» OUR STORE

Website: https://realtimehistory.net»CREDITS

Presented by: Jesse Alexander

Written by: Cathérine Pfauth, Prof. Dr. Tobias Arand, Jesse Alexander

Director: Toni Steller & Florian Wittig

Director of Photography: Toni Steller

Sound: Above Zero

Editing: Toni Steller

Motion Design: Philipp Appelt

Mixing, Mastering & Sound Design: http://above-zero.com

Maps: Battlefield Design https://www.battlefield-design.co.uk/

Research by: Cathérine Pfauth, Prof. Dr. Tobias Arand

Fact checking: Cathérine Pfauth, Prof. Dr. Tobias ArandChannel Design: Battlefield Design

Contains licensed material by getty images

All rights reserved – Real Time History GmbH 2021

July 2, 2021

Britain’s “agricultural revolution”

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes wonders about the almost-forgotten revolution that pre-dated the much better known Industrial Revolution:

Illustration of a seed drill from Horse-hoeing husbandry, 4th edition by Jethro Tull, 1762 (original work 1731).

Wikimedia Commons.

Whatever happened to “the Agricultural Revolution” of seventeenth and eighteenth-century Britain? In recent years I’ve hardly seen the term used at all, and the last major book on the subject was seemingly published twenty-five years ago. It has become almost totally eclipsed by its more famous sibling “the Industrial Revolution”, with its vivid associations of cotton, coal, and exponential hockey-stick graphs.

Yet for all that popularity, nearly every book investigating the causes of modern economic growth complains about the use of The Industrial Revolution. Even one of the pioneers of economic history, T. S. Ashton, who actually wrote the book The Industrial Revolution, complained on the very second page about the term’s inaccuracy. Much like “Holy Roman Empire”, there’s an error in every word. It involved too many series of changes to really be a The, was about so much more than just industry, and was too gradual a process to properly call a revolution. Yet Ashton had to concede that the term had “become so firmly embedded in common speech that it would be pedantic to offer a substitute.” And this was in 1948. In the intervening three quarters of a century, the term has become all the more difficult to dislodge.

I am, like everyone else, guilty of perpetuating the term Industrial Revolution. It’s a useful shorthand for people to at least get a rough idea of what I’m talking about, for me to then refine. Best to start with what people know, or at least what they think they know, and go from there. You may think of the Industrial Revolution as being about cotton, coal, and steam, but the period also saw major developments in every other industry, from agriculture to watch-making, and everything in-between. And so on. My preferred terms, like “acceleration of innovation”, always require at least a paragraph or two of explanation first.

With the term Agricultural Revolution, however, there’s just no need to reference it. Nobody really talks about it, or has anything more than a very vague conception of what it may mean. At best, people recall a few things from decades-old textbooks: names like “Turnip” Townshend or Jethro Tull, and perhaps a smattering of jargon like selective breeding, crop rotation, or enclosures. Even these are widely misunderstood. See last week’s post, for patrons, on how we get almost everything about the enclosure movement wrong. As for the Agricultural Revolution’s timing, who knows? When, over the course of the sixteenth, seventeenth, eighteenth, and maybe even nineteenth centuries is it supposed to have occurred? With the Industrial Revolution, there’s at least a “classic” period of 1760-1830, with a few decades of leeway. That is of course up for debate, and I’m especially keen on pushing it back much earlier, but it’s at least a half-decent starting point. With the Agricultural Revolution, there’s just no baseline at all. The experts themselves can’t agree.

For all that the term Agricultural Revolution has lost its salience, however, early modern changes to the productivity of agriculture were perhaps the most important of all. The ability to support a much larger population is itself a major economic achievement. For all that we obsess over historical measures of GDP per person, we often forget the much earlier and extraordinary increase in just the sheer number of people. In the early seventeenth century England’s population not only recovered to its pre-Black Death peak of about 5 million, but then from 1700 onwards it began to exceed it. By 1800, after just another century, the population of Britain had doubled to 10 million. And this in a period throughout which the country was a net exporter of grain.

March 19, 2021

QotD: English food

For someone who remembers the old days, the food is the most startling thing about modern England. English food used to be deservedly famous for its awfulness — greasy fish and chips, gelatinous pork pies, and dishwater coffee. Now it is not only easy to do much better, but traditionally terrible English meals have even become hard to find. What happened?

Maybe the first question is how English cooking got to be so bad in the first place. A good guess is that the country’s early industrialization and urbanization was the culprit. Millions of people moved rapidly off the land and away from access to traditional ingredients. Worse, they did so at a time when the technology of urban food supply was still primitive: Victorian London already had well over a million people, but most of its food came in by horse-drawn barge. And so ordinary people, and even the middle classes, were forced into a cuisine based on canned goods (mushy peas!), preserved meats (hence those pies), and root vegetables that didn’t need refrigeration (e.g. potatoes, which explain the chips).

But why did the food stay so bad after refrigerated railroad cars and ships, frozen foods (better than canned, anyway), and eventually air-freight deliveries of fresh fish and vegetables had become available? Now we’re talking about economics — and about the limits of conventional economic theory. For the answer is surely that by the time it became possible for urban Britons to eat decently, they no longer knew the difference. The appreciation of good food is, quite literally, an acquired taste — but because your typical Englishman, circa, say, 1975, had never had a really good meal, he didn’t demand one. And because consumers didn’t demand good food, they didn’t get it. Even then there were surely some people who would have liked better, just not enough to provide a critical mass.

And then things changed. Partly this may have been the result of immigration. (Although earlier waves of immigrants simply adapted to English standards — I remember visiting one fairly expensive London Italian restaurant in 1983 that advised diners to call in advance if they wanted their pasta freshly cooked.) Growing affluence and the overseas vacations it made possible may have been more important — how can you keep them eating bangers once they’ve had foie gras? But at a certain point the process became self-reinforcing: Enough people knew what good food tasted like that stores and restaurants began providing it — and that allowed even more people to acquire civilized taste buds.

Paul Krugman, “Supply, Demand, and English Food”, https://web.mit.edu/krugman/www/mushy.html.

February 21, 2021

Missing the point of the 1851 Great Exhibition

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes explains why the 1951 Festival of Britain failed to reproduce the success of the Great Exhibition of a century earlier, even though it did succeed in other ways:

The Crystal Palace from the northeast during the Great Exhibition of 1851, image from the 1852 book Dickinsons’ comprehensive pictures of the Great Exhibition of 1851

Wikimedia Commons.

… the idea that I tend to get most excited about, which I mentioned only in passing last month, is how we might resurrect the spirit of the nineteenth-century exhibitions of industry.

The best-known of these is undoubtedly the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations of 1851, still famous for its Crystal Palace. Held in Hyde Park, London, it attracted six million visitors, and has been emulated many times since. The World Fairs of today number the Great Exhibition as their first. Yet most people today don’t really appreciate what the Great Exhibition was actually for. They see it as a big, international event, with millions of visitors, who saw all sorts of fancy and exciting things — a chance for Britain, and many other countries since, to show off. The result is that many of the events that seek to capture something of the spirit of the original exhibition — 1951’s Festival of Britain, most of the World Fairs since the Second World War, the Millennium Experience, the 2018 Great Exhibition of the North, and now an upcoming “definitely-not-a-Festival-of-Brexit” (currently branded as Festival UK* 2022) — totally and utterly miss the point.

This is perhaps best illustrated by the runup to the 1951 Festival of Britain. Its proposers in the 1940s saw that the centenary of the Great Exhibition was coming up, so they proposed that there should be something similar to mark it. Yet by doing so, they did things entirely back-to-front. The Great Exhibition had a purpose; the exhibition was just the medium. It was the tool for a specific and sophisticated agenda. The Festival of Britain, by contrast, started with the idea of an exhibition, and then flailed about for a reason why. The government had a vague idea of organising an event to lift the country’s spirits after the Second World War, as well as to have it Britain-focused so as to craft a new national identity as the old empire disintegrated. But as its director-general Gerald Barry put it when they actually started work on the event: “we sat before our blotting pads industriously doodling, in the hope perhaps that a coherent pattern might eventually emerge, on the same principle that if you set down twelve apes before twelve typewriters they will (or so it is said) in the course of infinity type out the complete works of Shakespeare.”

Looking at the build-up to Festival UK* 2022, it’s hard not to get the same impression. The government wanted something to vaguely help craft a post-Brexit identity, on which it is happy to spend well over a hundred million pounds. Yet to make it happen it has funded a “research and development” project: a whole bunch of committees tasked with coming up with ideas of what to actually do (so far, it’s to be “a collection of ten large-scale, public engagement projects”). This is not to say that the event won’t, in some sense, succeed. The 1951 Festival of Britain, after all, was widely lauded. Barry’s twelve apes at their typewriters didn’t quite write Shakespeare, but they did manage to come up with something that many people remembered fondly. Perhaps some of the projects in 2022 will be similarly impressive.

Yet that doesn’t change the fact that the more recent projects miss the point. In fact, I’d say they are the exact inverse of the Great Exhibition. For a start, the 1851 event was entirely self-funded. It had government support, of course, including a cross-party Royal Commission to oversee the team that did the day-to-day running of things, but it raised its money through a public subscription and, when this was insufficient, took out a loan backed by a group of wealthy guarantors. Fortunately, the guarantors never had to pay out, as the event made so much through ticket sales that it was wildly profitable — so much so that the Royal Commission for the Great Exhibition of 1851 still exists. It purchased the 87 acres of land immediately south of the exhibition site, at South Kensington, for a more permanent collection of cultural institutions including many of London’s major museums. It helped fund a subsequent exhibition of industry on that site in 1862 — which actually had even more visitors, though it’s hardly remembered today. And even now, the Royal Commission continues to dispense over £3m every year to students and researchers.

That self-funding was important, I think, because it removed one of the main criticisms faced by modern large-scale events: that they are expensive wastes of taxpayer money on the vanity projects of politicians. The crowd-funding and finding of sufficient guarantors meant that the event needed to be accepted by the public at large, and even had them committed to the project before it had even begun. It necessitated a clear, exciting message from the get-go, rather than a post-hoc rationalisation.

And what was that message? For nineteenth-century organisers, an exhibition of industry was not just some grand display with a certain je ne sais quoi. It was intended as an engine of improvement: a direct way to actually encourage invention rather than just celebrate it, to raise the standards of consumers, and to lower barriers to trade. It was even a tool of industrial policy, and a springboard for reform.

February 14, 2021

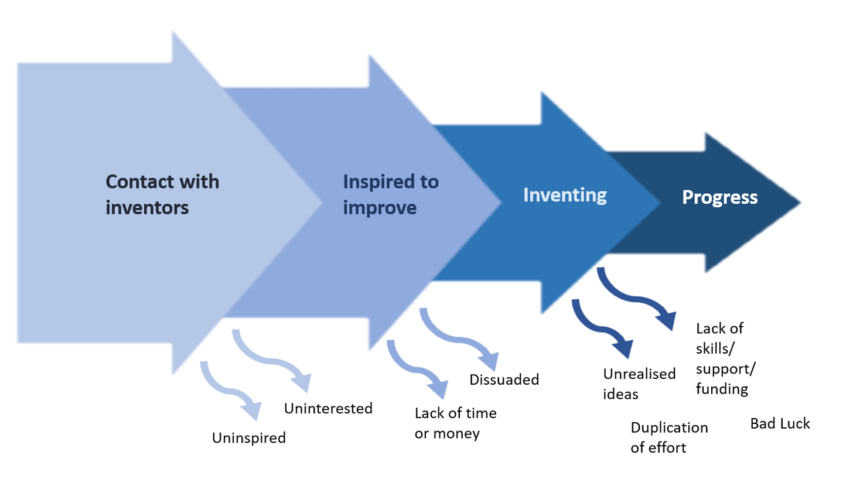

Helping to make more innovators

In the most recent Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes considers what “spark” seems to be needed to get people to think of innovations and how it can be done — albeit less efficiently — by reading about innovators or for more modern audiences, watching movies:

As I mentioned last time, increasing the supply of people becoming inventors is possibly one of the most significant, world-changing things that anyone can do. So I’ve been thinking a lot lately about what I call upstream policies: things that expose people to the idea of invention, increasing the chances that they themselves will be inspired with an improving mentality — a mindset of seeing problems where others do not, and then developing solutions to them. Contrary to “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it”, the inventor is the person who can’t help but see the extra potential to improve things, and can’t resist applying their fixes too.

During the Industrial Revolution, most exposure to invention seems to have been face-to-face. There are a handful of cases where reading about inventors may have played a role in inspiring some people to invent. John Harrison, the clockmaker who created a timepiece so advanced that it allowed sailors to find their longitude even at sea, was allegedly given a copy of the scientific lectures of Nicholas Saunderson by a visiting clergyman when he was just a boy. (Whether it was the book or really the clergyman who inspired him, however, it is difficult to say.) Likewise, Francis Maceroni, an early nineteenth-century pioneer of kite-surfing, who also applied himself to improving swimming, paddle wheels, rockets, asphalt paving, and steam carriages, among other things, seems to have first been exposed to innovation by reading various books on science, including the works of Benjamin Franklin. Or take the young George Stephenson, pioneer of railway locomotion, who read a history of inventions that apparently prompted him to try to invent a perpetual motion machine (before another book, this time on mechanics, revealed to him the error in trying).

Inspiration can be indirect, with the written word complementing face-to-face interactions, or even prompting them to seek them, as well as giving people a taste of the improving mentality. I suspect that books like Samuel Smiles’s bestseller Self Help — essentially a collection of pulled-themselves-up-by-their-bootstraps stories about inventors — played a part in inspiring people to also have a go at improvement in the late nineteenth century, a little after the period I mainly study.

Today, however, we have many more media available to us to encourage people to become inventors — from radio and film, to video games and various other kinds of social media. Yet I’m not sure we’re doing it all that well. As I mentioned last time, I’ve been working my way through a bunch of the films that were suggested to me (the list is here), and so far I have largely been disappointed.

January 23, 2021

Innovation is infectious … you catch it from other innovators

An interesting notion on how people innovate or invent is discussed in Anton Howes’ latest Age of Invention newsletter:

… my research on the Industrial Revolution has yielded a general model of how to think about it.

Core to the model is the observation that innovation spreads from person to person. It is a mentality, that we pick up from others. Of my sample of inventors, active c.1550-1850, the vast majority of them had had some kind of contact with an inventor before inventing anything themselves. So far, I’ve found evidence of that contact for about 83% of them, and for the remainder we frankly know next to nothing about them anyway. On the balance of probability, I suspect that all inventors had and continue to have such prior contact, even if the evidence has been lost to the mists of time.

Supposing I’m right about this — and there’s also more recent evidence from the largest and most detailed ever study of modern American inventors to support it — then such exposure to an inventor is the ultimate cause of innovation. Everything else we worry about when promoting innovation, from funding to intellectual property rights, or from education to social acceptance, is in a sense downstream of it.

Absent any exposure to inventors, people simply don’t become inventors. Knowing about invention as an activity is a necessary precondition to becoming an inventor yourself. The vast majority of people never innovate, for the very simple reason that it never occurs to them to do so. People are faced with problems all the time, but they generally have all sorts of pre-existing responses to them. Famine? The millennia-old response was to tighten belts or starve. Not to try to innovate with agricultural techniques. Trade route collapse? The millennia-old response was to take the hit, or try to shift to other familiar markets. Not to try to send ships into the icy unknown. As I’ve noticed time and time and time again, necessity is not the mother of invention. It only appears that way in retrospect — it’s when faced with a crisis that pre-existing inventors step forth to solve problems in ways they had already been investigating. Without them, there would be no such innovative response. Crises have an effect on the direction of invention — that is, on what problems people identify and then try to solve — but not on its underlying supply.

But this is not to say that exposure to an inventor is sufficient. Supposing you do meet an inventor. Your contact might be too fleeting to have an impact, or you might not be predisposed to be inspired by them. You might lack curiosity, or be distracted by some other preoccupation. Or perhaps the inventor you met might not be an especially inspiring person. Some people are simply more interesting than others. So from an initial spring of people who come into contact with inventors, we can immediately narrow the flow of new inventors down to those for whom such exposure actually had an impact.

But we then have to narrow it down further. Of the people who have met an inventor and been inspired by them, some might be distracted by other activities, or be dissuaded by social barriers, or lack the resources to tinker around with things, whether it be money or time.

January 1, 2021

The paradox of innovation – the more you have, the less impact each individual innovation has

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes considers the oddity that as the British economy expanded during the early Industrial Revolution, each new discovery had less and less direct impact on the economy as a whole:

What this means is that when there were even some slight improvements in agriculture alone, the effects on living standards could be dramatic. But absent such improvements, a rich culture of innovation affecting everything from clothes to watches to books, wine, glassware, metals, and pottery would have been almost entirely masked from the figures. Importantly, the same applies not only to the composition of average notional consumption baskets, but to the contributions of different sectors to the economy as a whole. While the total amount of food has increased dramatically for the past few hundred years, for example, agriculture’s share of the economy steadily fell (from over 40% of the English economy in 1600, and an even greater share of total employment, to less than 1% today, with a similar trend repeated worldwide). So the relative importance of your typical agricultural innovation for overall growth rates has fallen dramatically. Perhaps it’s no wonder that twentieth-century agricultural pioneers like Norman Borlaug still don’t really get their due.

The same goes, more recently, for manufacturing. The reason the textbooks always name Kay, Hargreaves, Crompton, Cartwright and Arkwright, is because they made improvements to what was already one of the most important sectors of the economy: textiles. In the eighteenth century, textiles as a whole accounted for a whopping 16-17% of the British economy. So any growth in the value of wool, linen, and increasingly cotton goods, had an appreciable impact on overall economic growth. Today, by contrast, you’d be hard pressed to find many sectors that account for even 5% of the country’s economy (except construction, and possibly financial services, depending on how broadly you define them). And while Britain may have long lost its role as the workshop of the world, textile production in China today still only accounts for about 7% of the country’s economy. To put it another way, the modern Arkwrights and Cartwrights and Cromptons of China, to have any comparable effect on national statistics, would have to make productivity improvements to their industry that are at least three times as impressive.

And impressive they are, though you won’t have heard of them. Arkwright and Crompton multiplied the number of threads that a single machine could spin, from one to dozens. Today, thread is spun by the thousands, at speeds they could have scarcely comprehended, and with entire factories hardly needing a single pair of human hands. Automatic sensors monitor the yarn’s tension and detect any defects while it is being spun, with robots even whizzing along to repair any snaps, able to find a loose end and piece the yarn together again — a task that once required the nimble fingers of small children. From an eighteenth-century perspective, our textile machines routinely now do magic, and are getting ever more fantastical every day. Imagine showing Arkwright the use of lasers in fading and cutting jeans.

But by replacing human labour, innovation has become ever more hidden. Many people don’t realise that British manufacturing is actually larger and more valuable than ever. It’s just that it employs fewer people than ever, so hardly anybody gets to witness its great strides forwards (to witness a flavour of manufacturing’s modern marvels, I recommend checking out MachinePix).

And more importantly, the overall effect of each innovation has also been steadily diluted — itself the result of growth. Innovation has, in a sense, been the victim of its own success. By creating ever more products, sprouting new industries, and diversifying them into myriad specialisms, we have shrunk the impact that any single improvement can have. When cotton was king, a handful of inventors might hope to affect the entire national textile industry in some way. Nowadays, there’s not a chance. Doubling the productivity of cotton spinning is all well and good, but what about nylon, polyester, rayon, and the host of other fibres we have since invented? And which kind of spinning machine would you improve? An old-fashioned ring-spinner, a newer rotor spinner, or perhaps even one of the brand new air-jet types?

If you make an improvement, it’s not going to be to the industry as a whole — it’ll be specific. And actually improvements have always been specific; it’s just that the industries have since multiplied and narrowed. Inventors once made drops into a puddle, but the puddle then expanded into an ocean. It doesn’t make the drops any less innovative. This paradox of progress affects all innovation, such that it is no wonder that the number of researchers has been increasing while national-level productivity growth has appeared fairly stagnant. Even general-purpose technologies, like the recent dramatic improvements to telecommunications, computing, and software, have had a muted effect, being applied more slowly than we’d have liked. I expect that all future general-purpose technologies will fare even worse, for it takes still further effort and innovation to apply a technology to a given industry, and those industries will continue to multiply. All future general-purpose technologies, that is, except improvements to energy.

December 14, 2020

Hall Model 1819: A Rifle to Change the Industrial World

Forgotten Weapons

Published 7 Sep 2020http://www.patreon.com/ForgottenWeapons

https://www.floatplane.com/channel/Fo…

Cool Forgotten Weapons merch! http://shop.bbtv.com/collections/forg…

John Hall designed the first breechloading rifle to be used by the United States military, and the first breechloader issued in substantial numbers by any military worldwide. His carbines would later be the first percussion arms adopted by any military force. Hall developed a breechloading flintlock rifle in 1811, had it tested by the military in 1818, and formally adopted as a specialty arm in 1819.

Hall’s contribution actually goes well beyond having a novel and advanced rifle design. He would be the first person to devise a system of machine tools capable of producing interchangeable parts without hand fitting, and this advance would be the foundation of the American system of manufacturing that would revolutionize industry worldwide. Hall did this work at the Harpers Ferry Arsenal, where he worked from 1819 until his death in 1841.

I plan to expand on the details of a variety of Hall rifle models in future videos, and today is meant to be an introduction to the system. Because it was never a primary arm in time of major war, Hall is much less well recognized than he should be among those interested in small arms history.

Contact:

Forgotten Weapons

6281 N. Oracle #36270

Tucson, AZ 85740

August 25, 2020

How we used to “dine out” (and someday might be able to again)

In The Critic, Alexander Larman reviews The Restaurant: A history of eating out by William Sitwell:

The recent enforced lockdown closure was a potential death blow to the entire [restaurant] industry. Which makes William Sitwell’s luxurious book both a celebration and an unintentional requiem for what may be a bygone time.

His central thesis is clear: the history of dining out is also a social history of evolving cultures and tastes. This means that the subjects he writes about range from ancient Pompeii to the growth of the sushi conveyor belt restaurant, encompassing everything from medieval taverns and the French Revolution to the rise of Anglo-Indian cuisine.

It is a broad and impressive spectrum, but perhaps Sitwell has, like some of the less fortunate people he describes, bitten off more than he can chew. His opening chapter about Pompeii is rich in surprising detail (graffiti uncovered outside one tavern when it was excavated ranged from the poetic — “Lovers are like bees in that they lead a honeyed life” — to the crude — “I screwed the barmaid”) and an insightful evocation of the dining culture in Ancient Rome.

He is then, unfortunately, faced with the insurmountable difficulty that the restaurant, as we know it today, did not exist until the late eighteenth century, meaning that his definition of “eating out” has to do some extremely heavy lifting.

There is as much padding in the early chapters as there is around some of his subjects’ waistlines. Much of what he writes is very interesting and often amusing, such as the way in which coffee, first drunk in London around the time of the Restoration, became associated both with health-giving properties and reportedly making men impotent, withered “cock-sparrows”. Yet there are also lengthy sections that have little or nothing to do with restaurants, such as a potted history of the Industrial Revolution.

Nevertheless, when Sitwell finally gets into his stride and begins to write about eateries proper, his authority and enthusiasm are palpable. He describes the dawn of fine dining in Paris in the nineteenth century evocatively. London lagged behind, although gentlemen’s clubs such as the Athenaeum and Reform offered some delights for the wealthy thanks to chefs (French, naturally) such as Alexis Soyer who implemented what one biographer called “the most famous and influential working kitchen in Europe” in 1841, complete with gas-fired stoves, butcher’s rooms and a fireplace devoted to the roasting of game and poultry.

August 16, 2020

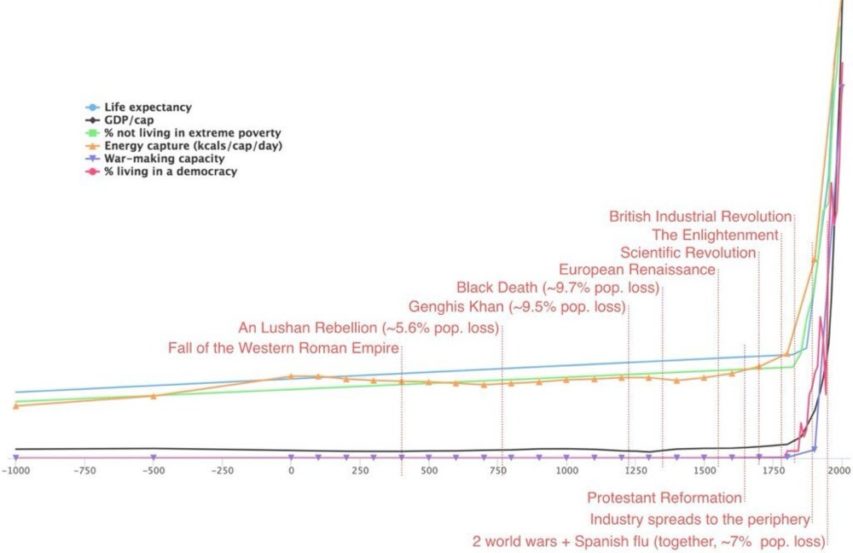

This is a “hockey stick” graph you can believe

Brian Micklethwait says this graph, unlike the more famous (debunked) “hockey stick”, shows one of the most important moments in human history:

If that graph, or another like it, is not entirely familiar to you, then it damn well should be. It pinpoints the moment when our own species started seriously looking after its own creature comforts. This was, you might say, the moment when most of us stopped being treated no better than farm animals, and we began turning ourselves into each others’ pets.

Patrick Crozier and I will be speaking about this amazing moment in the history of the human animal in our next recorded conversation. That will, if the conversation happens as we hope and the recording works as we hope, find its way to here.

I’m not usually one for podcasts, in the same way that I’m not an audiobook user: I find I’m unable to do other things while listening to the spoken word, and it’s always far faster to read a text than to have it read to you. In this particular case, I might try to make an exception, and give up hope of doing anything else productive while I listen.

August 3, 2020

Romanticizing the past

Sarah Hoyt points out that the past really is a foreign country and they do things very differently there … and for good reasons:

An image of coal pits in the Black Country from Griffiths’ Guide to the iron trade of Great Britain, 1873.

Image digitized by the Robarts Library of the University of Toronto via Wikimedia Commons.

So, quickly: The industrial revolution was not a disaster to your average peasant. It was a disaster for landowners.

Yes, yes, the conditions in the factories were terrible. By our standards. The lifespan was very short. By our standards. The anomie of the big cities, yadda yadda. When compared to what? Small villages? Ask those of us raised in them. Yes, there was child labor. As compared to what at that time? Other than the life of the upper classes?

Look, we don’t have to guess about this stuff. In India, in China, in other places that came to the industrial revolution very late, we’ve seen peasants leave the land where their ancestors had labored, to flock to the big cities, to take work we find horrible and exploitative at wages we find ridiculous.

And even if China has added “labor camp” and prisoner wrinkles to it, note that’s because China is a shitty communist country, not because the migration wasn’t there before. Also the labor camp aspects, as much as one can tell (and it’s hard to tell, due to the raging insanity of the regime) seem to have grown as the people grew more prosperous, as a result of the industrial revolution and thereby demanded higher wages, which positioned China more poorly as the “factory of the world.”

In fact, idealizing “living off the land” has been in place since at least the Roman empire, and probably before. It’s also been MISERABLE at least since then and probably before.

Because pre-industrial revolution farming sucked. It sucked horribly. And it kept you on the edge of subsistence. It double sucked when you were subjected to a Lord. Look, systems of serfdom, etc. didn’t come about because living in a Lord’s domain was so great, and everyone wove wreaths and danced around maypoles all the time, okay?

The bucolic paradise of a farmer’s life was mostly a creation of city dwellers, often noblemen, who saw it from the outside.

There are estimations that most people had trouble rearing even one child, and most of one generation’s peasants were people fallen from higher status. I don’t know. That might be exaggerated. Or it might not.

Even during the industrial revolution, it was normal for ladies bountiful to take baskets of food to tenant farmers because … they couldn’t make it on their own.

And btw, the more the industrial revolution pulled people to the cities, the more the Lords and “elites” talked about how great the countryside was and how terrible the factories/cities/new way of living were.

A lot of artists and pseudo bohemians jumped in on this bandwagon and so did Marx, who was both a pseudo bohemian, by birth “elite” (Well, his family had a virtual slave attached to him. He impregnated her too, as was his privilege), and by self-flattery intellectual.

Therefore the factories were the worst thing ever, the men who owned them, aka capitalists were terrible, terrible people — mostly because Marx wasn’t one, and probably because they laughed at him — and the proletariat they exploited horribly would rise up and —

All bullshit of course. Later on his fiction needed retconning by Anthony Gramsci who, having the sense to realize the “workers” weren’t rising up, just getting wealthier and escaping the clutches of the “elites” more made the “proletariat” a sort of “world proletariat” centered on poorer/more dysfunctional countries. This had the advantage of making the exploited masses always be elsewhere (or the supposed exploiters) and therefore made it easier to pitch group against group to the eternal profit of rather corrupt “elites.” Mostly political classes which are descended from “the best people.”

July 4, 2020

The birth of the steam age

In the latest installment of his Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes explores the very early steam age in England:

Why was the steam engine invented in England? An awful lot hinges on this question, because the answer often depends on our broader theories of what caused the British Industrial Revolution as a whole. And while I never tire of saying that Britain’s acceleration of innovation was about much, much more than just the “poster boy” industries of cotton, iron, and coal, the economy’s transition to burning fossil fuels was still an unprecedented and remarkable event. Before the rise of coal, land traditionally had to be devoted to either fuel, food, or clothing: typically forest for firewood, fields for grain, and pastures for wool-bearing sheep. By 1800, however, English coal was providing fuel each year equivalent to 11 million acres of forest — an area that would have taken up a third of the country’s entire surface area, and which was many times larger than its actual forest. By digging downward for coal, Britain effectively increased its breadth.

And coal found new uses, too. It had traditionally just been one among many different fuels that could be used to heat homes, alongside turf, gorse, firewood, charcoal, and even cow dung. When such fuels were used for industry, they were generally confined to the direct application of heat, such as in baking bricks, evaporating seawater to extract salt, firing the forges for blacksmiths, and heating the furnaces for glass-makers. Over the course of the seventeenth century, however, coal had increasingly become the fuel of choice for both heating homes and for industry. Despite its drawbacks — it was sooty, smelly, and unhealthy — in places like London it remained cheap while the price of other fuels like firewood steadily increased. More and more industries were adapted to burning it. It took decades of tinkering and experimentation, for example, to reliable use coal in the smelting of iron.

Yet with the invention of the steam engine, the industrial uses of coal multiplied further. Although the earliest steam engines generally just sucked the water out of flooded mines, by the 1780s they were turning machinery too. By the 1830s, steam engines were having a noticeable impact on British economic growth, and had been applied to locomotion. Steam boats, steam carriages, steam trains, and steam ships proliferated and began to shrink the world. Rather than just a source of heat, coal became a substitute for the motive power of water, wind, and muscle.

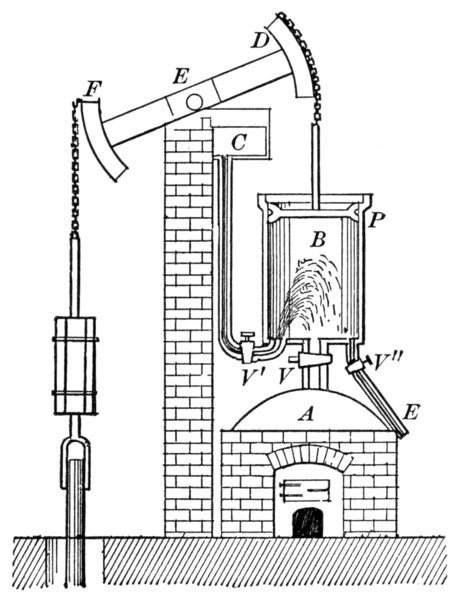

So where did this revolutionary invention come from? There were, of course, ancient forms of steam-powered devices, such as the “aeolipile”. Described by Hero of Alexandria in the 1st century, the aeolipile consisted of a hollow ball with nozzles, configured in such a way that the steam passing into the ball and exiting through the nozzles would cause the ball to spin. But this was more like a steam turbine than a steam engine. It could not do a whole lot of lifting. The key breakthroughs came later, in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, and instead exploited vacuums. In a steam engine the main force was applied, not by the steam itself pushing a piston, but by the steam within the cylinder being doused in cold water, causing it to rapidly condense. The resulting partial vacuum meant that the weight of the air — the atmospheric pressure — did the real lifting work. The steam was not there to push, but to be condensed and thus pull. It saw its first practical applications in the 1700s thanks to the work of a Devon ironmonger, Thomas Newcomen.

Science was important here. Newcomen’s engine could never have been conceived had it not been for the basic and not at all obvious observation that the air weighed something. It then required decades of experimentation with air pumps, barometers, and even gunpowder, before it was realised that a vacuum could rapidly be created through the condensation of steam rather than by trying to suck the air out with a pump. And it was still more decades before this observation was reliably applied to exerting force. An important factor in the creation of the steam engine was thus that there was a sufficiently large and well-organised group of people experimenting with the very nature of air, sharing their observations with one another and publishing — a group of people who, in England, formalised their socialising and correspondence in the early 1660s with the creation of the Royal Society.

Newcomen’s Atmospheric Steam Engine. The steam was generated in the boiler A. The piston P moved in a cylinder B. When the valve V was opened, the steam pushed up the piston. At the top of the stroke, the valve was closed, the valve V’ was opened, and a jet of cold water from the tank C was injected into the cylinder, thus condensing the steam and reducing the pressure under the piston. The atmospheric pressure above then pushed the piston down again.

Original illustration from Practical Physics for Secondary Schools. Fundamental principles and applications to daily life, by Newton Henry Black and Harvey Nathaniel Davis, 1913, via Wikimedia Commons.

June 25, 2020

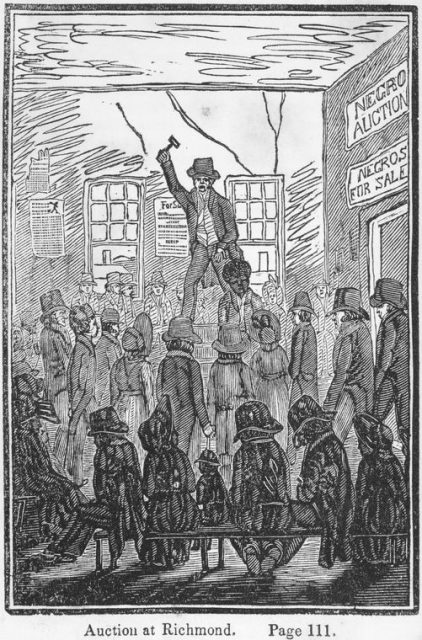

Capitalism and slavery

In Quillette, Matthew Lesh explains why glib claims that slavery was somehow “essential” to early capitalism or that slavery was the cause of western wealth just don’t hold up to any historical scrutiny:

Auction at Richmond. (1834)

“Five hundred thousand strokes for freedom; a series of anti-slavery tracts, of which half a million are now first issued by the friends of the Negro” by Wilson Armistead and “Picture of slavery in the United States of America” by George Bourne.

New York Public Library via Wikimedia Commons.

It has become a common trope that slavery and the slave trade is responsible for the industrial revolution, if not our entire modern prosperity. Slavery is often called capitalism’s “dark side.” A recent column in the Guardian claimed the slave trade “heralded the age of capitalism” and Guardian columnist George Monbiot said on Twitter: “The more we discover about our own history, the less the ‘trade’ on which Britain built its wealth looks like exchange, and the more it looks like looting. It meant extracting stolen resources and the products of slavery, debt bondage and land theft from other nations.” The same line has been taken by London Mayor Sadiq Khan, who tweeted: “It’s a sad truth that much of our wealth was derived from the slave trade.”

But what did the “father of modern economics,” Adam Smith, actually think about slavery? And is it responsible for our modern prosperity?

Adam Smith argued not only that slavery was morally reprehensible, but that it causes economic self-harm. He provided economic and moral ammunition for the abolitionist movement that came to fruition after his death in 1790. Smith was pessimistic about the potential for full abolition, but he was on the side of the angels.

Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, contains perhaps the best known economic critique of slavery. Smith argued that free individuals work harder and invest in the improvement of land, motivated by their interest in earning a higher income, than slaves. Smith refers to ancient Italy, where the cultivation of corn degraded under slavery. The cost of slavery is “in the end the dearest of any,” Smith writes.

His thinking about slavery can be traced further back. In the Lectures on Justice, Police, Revenue and Arms, delivered in 1763 long before Britain’s abolitionist movement was formalised, Smith writes:

Slaves cultivate only for themselves; the surplus goes to the master, and therefore they are careless about cultivating the ground to the best advantage. A free man keeps as his own whatever is above his rent, and therefore has a motive to industry.

Smith describes how serfs in Western Europe — in feudal relationships with lords — were progressively transformed into free tenants as they acquired cattle and tools. Harvests were more evenly divided between landlord and tenant to encourage better use of land, and tenants eventually progressed to simply giving the landlord a sum for lease. As government became more established, the influence of lords over the lives of tenants was also loosened.

Capitalism was, as Marx described, the next stage in human development after feudal slave relations. Smith’s commercial society is in direct opposition to a slave society. Smith, at his core, is an advocate for individuals being free to specialize and trade, including to trade their labor. Everyone acting with regard to their “own interest,” not because of coercion, creates general prosperity.

Smith’s case against slavery is proven by history: The huge uptick in human prosperity came largely after the end of feudal relations and the abolition of slavery and the slave trade. We are many magnitudes richer than when lords held slaves, or even chattel slavery proliferated in the Americas. The setting free of humanity led to extraordinary innovation and entrepreneurialism. This is only possible, as Smith argued, when individuals can benefit from the fruits of their own labor (slaves cannot hold property in their own name, and hence cannot trade or choose to specialise).

We didn’t become rich because a few hundred years ago people toiled on farms in awful conditions. In fact, the opposite. “It was precisely the replacement of human muscle power with that of steam and machines which did away with the vileness of chattel slavery and forced labor,” Tim Worstall has explained.

May 21, 2020

The Great Exhibition of 1851 also served (for some) as the 19th century equivalent of the “Missile Gap” controversy

In the latest edition of his Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes discusses the changing role of the British government and how the Great Exhibition was also useful as subtle domestic propaganda for a more active role for government in the British economy:

The Crystal Palace from the northeast during the Great Exhibition of 1851, image from the 1852 book Dickinsons’ comprehensive pictures of the Great Exhibition of 1851

Wikimedia Commons.

… a whole new opportunity for reform was provided by the Great Exhibition of 1851. As I explained in the previous newsletter, an international exhibition of industry functioned as an audit of the world’s industries. It, and its successors, the world’s fairs, gave some indication of how Britain stood relative to rival nations, especially France, Prussia, and the United States. And whereas some people saw the Great Exhibition as a clear mark of Britain’s superiority, for would-be reformers it was a chance to expose worrying weaknesses. Thus, Henry Cole and the other original organisers of the exhibition at the Society of Arts exacerbated fears of Britain’s impending decline, giving them an excuse to create the systems they desired.

They identified two areas of worry: science and design. Britain of course had many eminent scientists and artists — some of the best in the world — but other countries seemed to have become better at diffusing scientific training and superior taste throughout the workforce as a whole. Design skills were an issue because France appeared to be catching up with Britain when it came to the mechanisation of industry; if it caught up on machinery while maintaining its lead in fashion, then Britain would not be able to compete. And scientific training appeared more useful than ever, with the latest scientific advances “influencing production to an extent never before dreamt of”. Visitors to the Great Exhibition had marvelled at the recent inventions of artificial dyes, a method of processing beetroot sugar, and the latest improvements to photography and the electric telegraph. Thus, for Britain to maintain its lead, it would need to improve the education of its workers.

The reformers’ scare tactics worked. The aftermath of the Great Exhibition saw the creation of a government Department of Science and Art under the direction of Henry Cole, who in turn oversaw the agglomeration of various museums, design schools, and other cultural institutions to what is now the “Museum Mile” in South Kensington. (Curiously, the area was originally called Brompton, but when Cole opened a museum of design and industry there, he named it the South Kensington Museum. Kensington was a much more aristocratic area nearby, though it had no “south” at the time. The museum evolved, rather complicatedly, into what is now the Victoria & Albert Museum. But unlike so many top-down area re-brands, the name South Kensington stuck.)

And that was just the beginning. Cole and his allies then oversaw a dramatic expansion of the state into education, largely through the use of examinations. Although state-funding for education had initially centred on building new schools, getting any more involved was a highly contentious issue. Most schools were controlled and funded by religious organisations, but were split between the established Anglican church and dissenters. When the government first became involved in schools, it was thus bitterly opposed by many dissenters as they feared that their children might become indoctrinated to Anglicanism. And naturally, the government could not teach dissenting religions. Yet the proposed compromise of teaching no religion at all was unacceptable to both sides. Schools were crucial, the groups believed, to keeping religion alive.

So the utilitarians came up with a workaround. Rather than getting the state too involved directly in managing the schools themselves, it would instead influence the curriculum. By holding examinations, and then paying teachers based on the outcomes of the tests, they could incentivise the teaching of certain subjects and leave the schools free to teach whatever religious beliefs they pleased. Indeed, by diverting more and more time towards teaching particular subjects, the reformers saw it as a secularising blow “against parsonic influence”. The tactic was initially applied to adult education. The Society of Arts would first trial out examinations without payments, to test their viability. Then Cole would have his department take over the examinations, first for drawing, and later for science, using his budget to fund payment-by-results. The effects were dramatic. The Society’s relatively popular examinations in chemistry, for example, rarely had more than a hundred candidates a year. But when the department instituted its payments, it soon drew in thousands. By 1862, when the government wanted to improve the teaching of reading, writing, and arithmetic in schools, they adopted Cole’s suggestion that they also use payment-by-results.