Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 24 Jun 2025

Two majestic tiers of grapes, mandarin oranges, and raspberries suspended in pink champagne gelatin topped with whipped cream

City/Region: United States of America

Time Period: 1877The Gilded Age, a period of late 19th century United States history when a handful of people got mind-bogglingly wealthy off of industrialization, conjures up images of the social elite in New York. High society families had more money than most of us could imagine, and they spent it in the most ostentatious ways. One of those ways was by throwing parties that could cost up to the equivalent of millions of dollars in today’s money. These parties would host lavish feasts with dozens of dishes, like this gelée macédoine, which would have been served in a sweet course alongside plum puddings, mince pies, and fruit cakes.

I’m not normally a fan of gelatin, but this was really nice. It wasn’t rubbery at all and the champagne flavor really comes through. It takes a while to make, but feels fancy and is delicious. You could also use the recipe as a base and swap out other types of wine or use other flavorings like liqueurs or spices. If you do add spices (cinnamon was popular at the time), put them into the syrup, and be sure to use a cloth jelly bag or nut milk bag to strain the gelatin mixture. This will ensure a clear jelly.

If you don’t have a gelatin mold, you can use a bundt cake pan, or really any bowl of pan that you have.

Gelée Macédoine. This is made with any kind of jelly; however, jelly made with Champagne or sherry is preferable. Any of the delicate fruits of the season, such as grapes, cherries, peaches, strawberries, raspberries, mulberries, currants (on their stems), plums, and orange sections, or preserved fruits, such as brandied cherries, peaches, etc., are tastefully imbedded in the jelly, so as to show their forms and colors to best advantage.br/>

— Practical Cooking, and Dinner Giving by Mrs. Mary F. Henderson, New York City, 1877

December 1, 2025

Feeding the Robber Barons of the Gilded Age

October 12, 2025

Inventing boring Sundays – a British innovation

Ed West ruminates on the phenomenon of boring British Sundays and explains how they got that way:

Nietzsche thought that this was the whole idea, that the English designed Sundays that way in order to encourage people to appreciate the working week. In Beyond Good and Evil, he described how “The industrious races complain a great deal about having to tolerate idleness: it was a masterpiece of the English instinct to make Sunday so holy and so tedious, a form of cleverly invented and shrewdly introduced fasting, that the Englishman, without being aware of the fact, became eager again for weekdays and workdays.”

There may be some truth in this, so that before the Industrial Revolution there was the “Industriousness Revolution”, with a new emphasis on work rather than leisure. This is something which Joseph Henrich noted from studying reports from the Old Bailey between 1748 to 1803, and “spot-checks” observations about what Londoners were doing at a particular moment:

The data suggest that the workweek lengthened by 40 percent over the second half of the 18th century. This occurred as people stretched their working time by about 30 minutes per day, stopped taking “Saint Mondays” off (working every day except Sunday), and started working on some of the 46 holy days found on the annual calendar. The upshot was that by the start of the 19th century, people were working about 1,000 hours more per year, or about an extra 19 hours per week.

Before the Industriousness Revolution it was common for people to enjoy a number of saints’ days as holidays, including the three-day weekends offered by these “Saint Mondays”. That all changed with the arrival of Protestantism, with its scepticism towards saints’ days, William Tyndale arguing that these were only celebrated by convention and that there wasn’t anything special about them.

While they were keen to abolish holidays, the reformers also believed in making the Sabbath more godly, and so the Boring English Sunday was invented. This followed from a growing sense that leisure time was wasted time, but it was also the case that many of the Protestant reformers just didn’t like people having fun. In God is an Englishman, Bijan Omrani noted how “From the end of the 1500s, Puritan preachers condemned the way people generally spent their Sundays: ‘full heathenishly, in taverning, tippling, gaming, playing and beholding bear-baitings and stage-plays, to the utter dishonour of God'”.

Theologian William Perkins believed that Sunday “should be a day set apart for the worship of God and the increase in duties of religion”. Lincolnshire cleric John Cotton said in 1614 that it should be unlawful to pass Sunday without hearing at least two sermons; the idea of going to church twice would have filled my ten-year-old self with intense horror.

Hugh Latimer asked: “What doth the people do on these holidays? Do they give themselves to godliness, or else ungodliness … God seeth all the whole holidays to be spent miserably in drunkenness, in glossing, in strife, in envy, in dancing, dicing, idleness, and gluttony”.

Latimer also disliked holidays for quite modern-sounding reasons related to social inequality, noting that “in so many holidays rich and wealthy persons … flow in delicates, and men that live by their travail, poor men … lack necessary meat and drink for their wives and their children, and … they cannot labour upon the holidays, except they will be cited, and brought before our officials”.

The reverse argument is now made against allowing supermarkets to drop Sunday trading hours – that it pressures working people into excessive toil so that Waitrose shoppers don’t suffer any inconvenience. Although, reading Latimer, I can’t help but suspect that his real objection was to people having fun.

The reformers won, and English Sundays became notably dull. Banjani quoted children’s writer Alison Uttley, who said of Sundays that “Nobody ever read a newspaper or whistled a tune except hymns”.

April 8, 2025

Free trade, the once-and-future left wing cause

Let’s join Tim Worstall on a brief trip into economic history, when free trade was a pet issue for the left (because it helped the poor and the working class) and protectionism was the position of the right (because it helped the wealthy and the aristocracy):

The people who suffer here are the consumers in the US. The people who benefit are the capitalists in the US. Which is why free trade always has been a left wing position. True, many lefties in recent decades have somewhat strayed from the one true path but given that it’s Trump imposing them some seem to be coming back. Although how much of that is about TDS and how much about reality is still unknown.

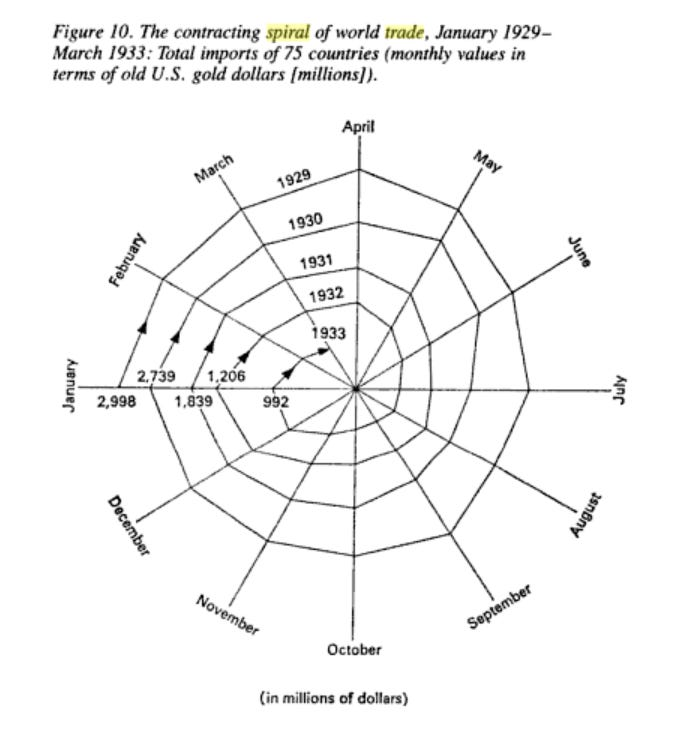

We’ve also got that little point about what happened last time around:

That all started with eggs. There’s fuss about eggs in the US at present. My, how history echoes, eh?

There’s only the one logical, moral or ethical position to have upon trade. As I’ve pointed out before with my model trade treaty:

Note that this applies to all ideas about tariffs — with the one exception of national security where we are indeed willing to give up direct economic benefit in order to keep the French at bay. To tariffs for industrial policy, tariffs for Green, tariffs for trade wars, tariffs as revenue raisers, tariffs, see?

We should remind ourselves that the opposition to Adam Smith and his ideas came from the conservatives. Cobden and the Manchester Liberals were the left wing betes noires of their day. The Guardian was actually set up as a newspaper to push their ideas including that dread free trade.

We did actually get free trade too, in 1846. Which, not by coincidence, is when the Engels Pause stopped happening. Which was, itself, the observation by Karl’s buddy that while the British economy had grown lots — industrialisation, capitalism, etc. — the living standards of the base people hadn’t, not very much. Of course, he was missing a bit — that ability to have a change of cotton underwear even for skivvies (aha, skivvies for skivvies even …) would only feel like an advance to those who had, previously, had to wear woollen knickers. This changed, living standards for the oiks began to rise, strongly, once we had free trade.

Now, there are a few of us still keepers of that sacred flame. But just to lay out the basic argument.

Average wages in an economy are determined by average productivity in that economy. Trade doesn’t, therefore, change wages — not nominal wages that is. Trade does change which jobs are done. That working out of comparative advantage means that we’ll do the things we’re — relative to our own abilities — less bad at and therefore are more productive at. Trade increases domestic productivity and thereby, in the second iteration, raises wages.

Trade also — obviously — gives us access to those things that J Foreigner is more productive at than we are — those things that are cheaper if Foreign, J, does them. This raises real wages again because we get more for our money. We’re better off. This is true whatever the tariffs our own exports face.

Finally, trade doesn’t affect the number of jobs in an economy — that’s determined by the balance of fiscal and monetary policy.

So, who benefits from trade restrictions? Well, the people who lose out from free trade are the domestic capitalists. Pre-1846 it was the still near feudal landlords in fact. What killed those grand aristocratic fortunes was not war nor tax — pace Piketty et al — it was free trade which destroyed agricultural rents.

The same is true today. The people who benefit from tariffs are the domestic capitalists who get to charge higher prices, make larger profits, as a result. The people who lose are all consumers plus, over time, all domestic workers as well. Tariffs increase the capitalist expropriation of the wages of the workers that is.

Tariffs are a right wing, neo-feudal, impoverishment of the people. Free trade is the ultimate leftypolicy to beat back the capitalists.

January 13, 2025

October 6, 2024

The rise of coal as a fuel in England

In the latest instalment of Age of Invention, Anton Howes considers the reasons for the rise of coal and refutes the frequently deployed “just so” story that it was driven by mass deforestation in England:

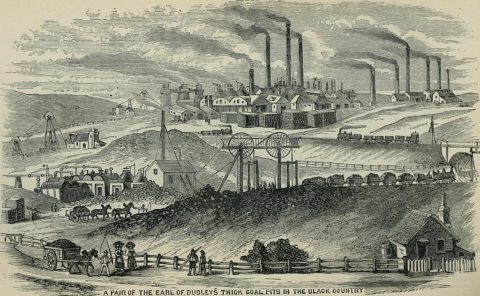

An image of coal pits in the Black Country from Griffiths’ Guide to the iron trade of Great Britain, 1873.

Image digitized by the Robarts Library of the University of Toronto via Wikimedia Commons.

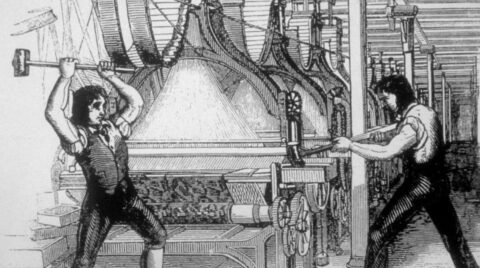

It’s long bothered me as to why coal became so important in Britain. It had sat in the ground for millennia, often near the surface. Near Newcastle and Sunderland it was often even strewn out on the beaches.1 Yet coal had largely only been used for some very specific, small-scale uses. It was fired in layers with limestone to produce lime, largely used in mortar for stone and brick buildings. And it had long been popular among blacksmiths, heating iron or steel in a forge before shaping it into weapons or tools.2

Although a few places burned coal for heating homes, this was generally only done in places where the coal was an especially pure, hard, and rock-like anthracite, such as in southern Wales and in Lowlands Scotland. Anthracite coal could even be something of a luxury fuel. It was burned in the palaces of the Scottish kings.3 But otherwise, the sulphur in the more crumbly and more common coal, like that found near Newcastle, meant that the smoke reeked, reacting with the moisture of people’s eyes to form sulphurous acid, and so making them sting and burn. The very poorest of the poor might resort to it, but the smoke from sulphurous coal fires was heavy and lingering, its soot tarnishing clothes, furnishings, and even skin, whereas a wood fire could be lit in a central open hearth, its smoke simply rising through the rafters and finding its way out through the various crevices and openings of thatched and airy homes. Coal was generally the inferior fuel.

But despite this inferiority, over the course of the late sixteenth century much of the populated eastern coast of England, including the rapidly-expanding city of London, made the switch to burning the stinking, sulphurous, low-grade coal instead of wood.

By far the most common explanation you’ll hear for this dramatic shift, much of which took place over the course of just a few decades c.1570-1600, is that under the pressures of a growing population, with people requiring ever more fuel both for industry and to heat their homes, England saw dramatic deforestation. With firewood in ever shorter supply, its price rose so high as to make coal a more attractive alternative, which despite its problems was at least cheap. This deforestation story is trotted out constantly in books, on museum displays, in conversation, on social media, and often even by experts on coal and iron. I must see or hear it at least once a week, if not more. And there is a mountain of testimonies from contemporaries to back the story up. Again and again, people in the late sixteenth and the seventeenth centuries complained that the woods were disappearing, and that wood fuel prices were on the rise.

And yet the deforestation thesis simply does not work. In fact it makes no sense at all.

Not out of the Woods Yet

This should immediately be obvious from even just a purely theoretical perspective, because wood was almost never exploited for fuel as a one-off resource. It was not like coal or peat or oil, which once dug out of the ground and burned could only be replaced by finding more. It was not a matter of cutting swathes of forest down and burning every branch, stump and root, leaving the land barren and going off in search of more. Our sixteenth-century ancestors were not like Saruman, destroying Fangorn forest for fuel. Instead, acres of forest, and even just the shrubs and trees that made up the hedges separating fields, were carefully maintained to provide a steady yield. The roots of trees were left living and intact, with the wood extracted by cutting away the trunk at the stump, or even just the branches or twigs — a process known as coppicing, and for branches pollarding — so that new trunks or branches would be able to grow back. Although some trees might be left for longer to grow into longer and thicker wood fit for timber, the underwoods were more regularly cropped.4

Given forests were treated as a renewable resource, claiming that they were cut down to cause the price of firewood to rise is like claiming that if energy became more expensive today, then we’d use all the water behind a hydroelectric dam and then immediately fill in the reservoir with rubble. Or it’s like claiming that rising food prices would result in farmers harvesting a crop and then immediately concreting over their fields. What actually happens is the precise opposite: when the things people make become more valuable, they tend to expand production, not destroy it. High prices would have prompted the English to rely on forests more, not to cut them down.

When London’s medieval population peaked — first in the 1290s before a devastating famine, and again in the 1340s on the eve of the Black Death — prices of wood fuel began to rise out of all proportion to other goods. But London had plenty of nearby woodland — wood is extremely bulky compared to its value, so trees typically had to be grown as close as possible to the city, or else along the banks of the Thames running through it, or along the nearby coasts. With the rising price of fuel, however, the city did not even have to look much farther afield for its wood, and nearby coastal counties even continued to export firewood across the Channel to the Low Countries (present-day Belgium and the Netherlands) and to the northern coast of France.5 A few industries did try to shift to coal, with lime-makers and blacksmiths substituting it for wood more than before, and with brewers and dyers seemingly giving it a try. But the stinking smoke rapidly resulted in the brewers and dyers being banned from using it, and there was certainly no shift to coal being burnt in people’s homes.6

1. Ruth Goodman, The Domestic Revolution (Michael O’Mara Books, 2020), p.91

2. James A. Galloway, Derek Keene, and Margaret Murphy, “Fuelling the City: Production and Distribution of Firewood and Fuel in London’s Region, 1290-1400”, The Economic History Review 49, no. 3 (1996): pp.447–9

3. J. U. Nef, The Rise of the British Coal Industry, Vol. 1 (London: George Routledge and Sons, 1932), p.107, pp.115-8

4. Oliver Rackham, Ancient Woodland: Its History, Vegetation and Uses in England (Edward Arnold, 1980), pp.3-6 is the best and clearest summary I have seen.

5. Galloway et al.

6. John Hatcher, The History of the British Coal Industry: Volume 1: Before 1700: Towards the Age of Coal (Oxford University Press, 1993), p.25

June 1, 2024

March 13, 2024

QotD: Filthy coal

… coal smoke had dramatic implications for daily life even beyond the ways it reshaped domestic architecture, because in addition to being acrid it’s filthy. Here, once again, [Ruth] Goodman’s time running a household with these technologies pays off, because she can speak from experience:

So, standing in my coal-fired kitchen for the first time, I was feeling confident. Surely, I thought, the Victorian regime would be somewhere halfway between the Tudor and the modern. Dirt was just dirt, after all, and sweeping was just sweeping, even if the style of brushes had changed a little in the course of five hundred years. Washing-up with soap was not so very different from washing-up with liquid detergent, and adding soap and hot water to the old laundry method of bashing the living daylights out of clothes must, I imagined, make it a little easier, dissolving dirt and stains all the more quickly. How wrong could I have been.

Well, it turned out that the methods and technologies necessary for cleaning a coal-burning home were fundamentally different from those for a wood-burning one. Foremost, the volume of work — and the intensity of that work — were much, much greater.

The fundamental problem is that coal soot is greasy. Unlike wood soot, which is easily swept away, it sticks: industrial cities of the Victorian era were famously covered in the residue of coal fires, and with anything but the most efficient of chimney designs (not perfected until the early twentieth century), the same thing also happens to your interior. Imagine the sort of sticky film that settles on everything if you fry on the stove without a sufficient vent hood, then make it black and use it to heat not just your food but your entire house; I’m shuddering just thinking about it. A 1661 pamphlet lamented coal smoke’s “superinducing a sooty Crust or Furr upon all that it lights, spoyling the moveables, tarnishing the Plate, Gildings and Furniture, and corroding the very Iron-bars and hardest Stones with those piercing and acrimonious Spirits which accompany its Sulphure.” To clean up from coal smoke, you need soap.

“Coal needs soap?” you may say, suspiciously. “Did they … not use soap before?” But no, they (mostly) didn’t, a fact that (like the famous “Queen Elizabeth bathed once a month whether she needed it or not” line) has led to the medieval and early modern eras’ entirely undeserved reputation for dirtiness. They didn’t use soap, but that doesn’t mean they didn’t clean; instead, they mostly swept ash, dust, and dirt from their houses with a variety of brushes and brooms (often made of broom) and scoured their dishes with sand. Sand-scouring is very simple: you simply dampen a cloth, dip it in a little sand, and use it to scrub your dish before rinsing the dirty sand away. The process does an excellent job of removing any burnt-on residue, and has the added advantage of removed a micro-layer of your material to reveal a new sterile surface. It’s probably better than soap at cleaning the grain of wood, which is what most serving and eating dishes were made of at the time, and it’s also very effective at removing the poisonous verdigris that can build up on pots made from copper alloys like brass or bronze when they’re exposed to acids like vinegar. Perhaps more importantly, in an era where every joule of energy is labor-intensive to obtain, it works very well with cold water.

The sand can also absorb grease, though a bit of grease can actually be good for wood or iron (I wash my wooden cutting boards and my cast-iron skillet with soap and water,1 but I also regularly oil them). Still, too much grease is unsanitary and, frankly, gross, which premodern people recognized as much as we do, and particularly greasy dishes, like dirty clothes, might also be cleaned with wood ash. Depending on the kind of wood you’ve been burning, your ashes will contain up to 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH), better known as lye, which reacts with your grease to create a soap. (The word potassium actually derives from “pot ash,” the ash from under your pot.) Literally all you have to do to clean this way is dump a handful of ashes and some water into your greasy pot and swoosh it around a bit with a cloth; the conversion to soap is very inefficient (though if you warm it a little over the fire it works better), but if your household runs on wood you’ll never be short of ashes. As wood-burning vanished, though, it made more sense to buy soap produced industrially through essentially the same process (though with slightly more refined ingredients for greater efficiency) and to use it for everything.

Washing greasy dishes with soap rather than ash was a matter of what supplies were available; cleaning your house with soap rather than a brush was an unavoidable fact of coal smoke. Goodman explains that “wood ash also flies up and out into the room, but it is not sticky and tends to fall out of the air and settle quickly. It is easy to dust and sweep away. A brush or broom can deal with the dirt of a wood fire in a fairly quick and simple operation. If you try the same method with coal smuts, you will do little more than smear the stuff about.” This simple fact changed interior decoration for good: gone were the untreated wood trims and elaborate wall-hangings — “[a] tapestry that might have been expected to last generations with a simple routine of brushing could be utterly ruined in just a decade around coal fires” — and anything else that couldn’t withstand regular scrubbing with soap and water. In their place were oil-based paints and wallpaper, both of which persist in our model of “traditional” home decor, as indeed do the blue and white Chinese-inspired glazed ceramics that became popular in the 17th century and are still going strong (at least in my house). They’re beautiful, but they would never have taken off in the era of scouring with sand; it would destroy the finish.

But more important than what and how you were cleaning was the sheer volume of the cleaning. “I believe,” Goodman writes towards the end of the book, “there is vastly more domestic work involved in running a coal home in comparison to running a wood one.” The example of laundry is particularly dramatic, and her account is extensive enough that I’ll just tell you to read the book, but it goes well beyond that:

It is not merely that the smuts and dust of coal are dirty in themselves. Coal smuts weld themselves to all other forms of dirt. Flies and other insects get entrapped in it, as does fluff from clothing and hair from people and animals. to thoroughly clear a room of cobwebs, fluff, dust, hair and mud in a simply furnished wood-burning home is the work of half an hour; to do so in a coal-burning home — and achieve a similar standard of cleanliness — takes twice as long, even when armed with soap, flannels and mops.

And here, really, is why Ruth Goodman is the only person who could have written this book: she may be the only person who has done any substantial amount of domestic labor under both systems who could write. Like, at all. Not that there weren’t intelligent and educated women (and it was women doing all this) in early modern London, but female literacy was typically confined to classes where the women weren’t doing their own housework, and by the time writing about keeping house was commonplace, the labor-intensive regime of coal and soap was so thoroughly established that no one had a basis for comparison.

Jane Psmith, “REVIEW: The Domestic Revolution by Ruth Goodman”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-05-22.

1. Yeah, I know they tell you not to do this because it will destroy the seasoning. They’re wrong. Don’t use oven cleaner; anything you’d use to wash your hands in a pinch isn’t going to hurt long-chain polymers chemically bonded to cast iron.

March 10, 2024

Viking longships and textiles

Virginia Postrel reposts an article she originally wrote for the New York Times in 2021, discussing the importance of textiles in history:

The Sea Stallion from Glendalough is the world’s largest reconstruction of a Viking Age longship. The original ship was built at Dublin ca. 1042. It was used as a warship in Irish waters until 1060, when it ended its days as a naval barricade to protect the harbour of Roskilde, Denmark. This image shows Sea Stallion arriving in Dublin on 14 August, 2007.

Photo by William Murphy via Wikimedia Commons.

Popular feminist retellings like the History Channel’s fictional saga Vikings emphasize the role of women as warriors and chieftains. But they barely hint at how crucial women’s work was to the ships that carried these warriors to distant shores.

One of the central characters in Vikings is an ingenious shipbuilder. But his ships apparently get their sails off the rack. The fabric is just there, like the textiles we take for granted in our 21st-century lives. The women who prepared the wool, spun it into thread, wove the fabric and sewed the sails have vanished.

In reality, from start to finish, it took longer to make a Viking sail than to build a Viking ship. So precious was a sail that one of the Icelandic sagas records how a hero wept when his was stolen. Simply spinning wool into enough thread to weave a single sail required more than a year’s work, the equivalent of about 385 eight-hour days. King Canute, who ruled a North Sea empire in the 11th century, had a fleet comprising about a million square meters of sailcloth. For the spinning alone, those sails represented the equivalent of 10,000 work years.

Ignoring textiles writes women’s work out of history. And as the British archaeologist and historian Mary Harlow has warned, it blinds scholars to some of the most important economic, political and organizational challenges facing premodern societies. Textiles are vital to both private and public life. They’re clothes and home furnishings, tents and bandages, sacks and sails. Textiles were among the earliest goods traded over long distances. The Roman Army consumed tons of cloth. To keep their soldiers clothed, Chinese emperors required textiles as taxes.

“Building a fleet required longterm planning as woven sails required large amounts of raw material and time to produce,” Dr. Harlow wrote in a 2016 article. “The raw materials needed to be bred, pastured, shorn or grown, harvested and processed before they reached the spinners. Textile production for both domestic and wider needs demanded time and planning.” Spinning and weaving the wool for a single toga, she calculates, would have taken a Roman matron 1,000 to 1,200 hours.

Picturing historical women as producers requires a change of attitude. Even today, after decades of feminist influence, we too often assume that making important things is a male domain. Women stereotypically decorate and consume. They engage with people. They don’t manufacture essential goods.

Yet from the Renaissance until the 19th century, European art represented the idea of “industry” not with smokestacks but with spinning women. Everyone understood that their never-ending labor was essential. It took at least 20 spinners to keep a single loom supplied. “The spinners never stand still for want of work; they always have it if they please; but weavers are sometimes idle for want of yarn,” the agronomist and travel writer Arthur Young, who toured northern England in 1768, wrote.

Shortly thereafter, the spinning machines of the Industrial Revolution liberated women from their spindles and distaffs, beginning the centuries-long process that raised even the world’s poorest people to living standards our ancestors could not have imagined. But that “great enrichment” had an unfortunate side effect. Textile abundance erased our memories of women’s historic contributions to one of humanity’s most important endeavors. It turned industry into entertainment. “In the West,” Dr. Harlow wrote, “the production of textiles has moved from being a fundamental, indeed essential, part of the industrial economy to a predominantly female craft activity.”

February 16, 2024

What remains of the “first” steam powered passenger railway line?

Bee Here Now

Published 23 Oct 2023The Stockton-Darlington Railway wasn’t the first time steam locomotives had been used to pull people, but it was the first time they had been used to pull passengers over any distance worth talking about. In 1825 that day came when a line running all the way from the coal pits in the hills around County Durham to the River Tees at Stockton was opened officially. This was an experiment, a practice, a great endeavour by local businessmen and engineers, such as the famous George Stephenson, who astounded crowds of onlookers with the introduction of Locomotion 1 halfway along the line, which began pulling people towards Darlington and then the docks at Stockton.

This was a day that would not only transform human transportation forever, but accelerate the industrial revolution to a blistering pace.

In this video I want to look at what remains of that line — not the bit still in use between the two towns, but the bit out in the coalfields. And I want to see how those early trailblazers tackled the rolling hills, with horses and stationary steam engines to create a true amalgamation of old-world and new-world technologies.

(more…)

November 26, 2023

QotD: From Industrial Revolution labour surplus to modern era academic surplus

Back in Early Modern England, enclosure led to a massive over-supply of labor. The urge to explore and colonize was driven, to an unknowable but certainly large extent, by the effort to find something for all those excess people to DO. The fact that they’d take on the brutal terms of indenture in the New World tells you all you need to know about how bad that labor over-supply made life back home. The same with “industrial innovation”. The first Industrial Revolution never lacked for workers, and indeed, Marxism appealed back in its day because the so-called “Iron Law of Wages” seemed to apply — given that there were always more workers than jobs …

The great thing about industrial work, though, is that you don’t have to be particularly bright to do it. There’s always going to be a fraction of the population that fails the IQ test, no matter how low you set the bar, but in the early Industrial Revolution that bar was pretty low indeed. So much so, in fact, that pretty soon places like America were experiencing drastic labor shortages, and there’s your history of 19th century immigration. The problem, though, isn’t the low IQ guys. It’s the high-IQ guys whose high IQs don’t line up with remunerative skills.

My academic colleagues were a great example, which is why they were all Marxists. I make fun of their stupidity all the time, but the truth is, they’re most of them bright enough, IQ-wise. Not geniuses by any means, but let’s say 120 IQ on average. Alas, as we all know, 120-with-verbal-dexterity is a very different thing from 120-and-good-with-a-slide-rule. Academics are the former, and any society that wants to remain stable HAS to find something for those people to do. Trust me on this: You do not want to be the obviously smartest guy in the room when everyone else in the room is, say, a plumber. This is no knock on plumbers, who by and large are cool guys, but it IS a knock on the high-IQ guy’s ego. Yeah, maybe I can write you a mean sonnet, or a nifty essay on the problems of labor over-supply in 16th century England, but those guys build stuff. And they get paid.

Those guys — the non-STEM smart guys — used to go into academia, and that used to be enough. Alas, soon enough we had an oversupply of them, too, which is why academia soon became the academic-industrial complex. 90% of what goes on at a modern university is just make-work. It’s either bullshit nobody needs, like “education” majors, or it’s basically just degrees in “activism”. It’s like Say’s Law for retards — supply creates its own demand, in this case subsidized by a trillion-dollar student loan industry. Better, much better, that it should all be plowed under, and the fields salted.

Any society digging itself out of the rubble of the future should always remember: No overproduction of elites!

Severian, “The Academic-Industrial Complex”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-05-30.

November 25, 2023

Crystal Palace Station is Needlessly Magnificent

Jago Hazzard

Published 9 Aug 2023Crystal Palace and the station built for it. Well, one of them.

(more…)

November 19, 2023

Ted Gioia wonders if we need a “new Romanticism”

He raised the question earlier this year, and it’s sticking with him to the point he’s gathering notes on the original Romantic movement and what it was reacting against:

I realized that, the more I looked at what happened circa 1800, the more it reminded me of our current malaise.

- Rationalist and algorithmic models were dominating every sphere of life at that midpoint in the Industrial Revolution — and people started resisting the forces of progress.

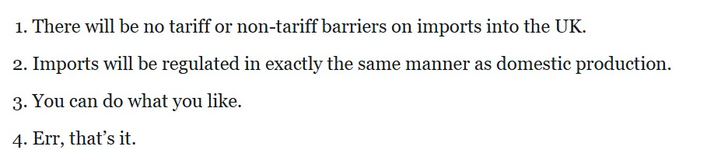

- Companies grew more powerful, promising productivity and prosperity. But Blake called them “dark Satanic mills” and Luddites started burning down factories — a drastic and futile step, almost the equivalent of throwing away your smartphone.

- Even as science and technology produced amazing results, dysfunctional behaviors sprang up everywhere. The pathbreaking literary works from the late 1700s reveal the dark side of the pervasive techno-optimism — Goethe’s novel about Werther’s suicide [Wiki], the Marquis de Sade’s nasty stories [Wiki], and all those gloomy Gothic novels [Wiki]. What happened to the Enlightenment?

- As the new century dawned, the creative class (as we would call it today) increasingly attacked rationalist currents that had somehow morphed into violent, intrusive forces in their lives — an 180 degree shift in the culture. For Blake and others, the name Newton became a term of abuse.

- Artists, especially poets and musicians, took the lead in this revolt. They celebrated human feeling and emotional attachments — embracing them as more trustworthy, more flexible, more desirable than technology, profits, and cold calculation.

That’s the world, circa 1800.

The new paradigm shocked Europe when it started to spread. Cultural elites had just assumed that science and reason would control everything in the future. But that wasn’t how it played out.

Resemblances with the current moment are not hard to see.

“Imagine a growing sense that algorithmic and mechanistic thinking has become too oppressive. Imagine if people started resisting technology. Imagine a revolt against STEM’s dominance. Imagine people deciding that the good life starts with NOT learning how to code.”

These considerations led me, about nine months ago, to conduct a deep dive into the history of the Romanticist movement. I wanted to see what the historical evidence told me.

I’ve devoted hours every day to this — reading stacks of books, both primary and secondary sources, on the subject. I’ve supplemented it with a music listening program and a study of visual art from the era.

What’s my goal? I’m still not entirely sure.

November 15, 2023

July 29, 2023

May 27, 2023

The true purpose of the Great Exhibition of 1851

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes considers the “why” of the 1851 Great Exhibition:

The Crystal Palace from the northeast during the Great Exhibition of 1851, image from the 1852 book Dickinsons’ comprehensive pictures of the Great Exhibition of 1851

Wikimedia Commons.

Ever since researching my book on the history of the Royal Society of Arts, I’ve been fascinated by the Great Exhibition of 1851, which they initiated. Like most people, I had once assumed that the exhibition was just a big celebration of Victorian technological superiority — a brash excuse to rub the British Industrial Revolution in the rest of the world’s faces. But my research into the origins of the event revealed that it was almost the opposite. Far from being a jingoistic expression of superiority, it was actually motivated by a worry that Britain was rapidly losing its place. It was an attempt to prevent decline by learning from other countries. It was largely about not falling behind.

Industrial exhibitions already had a long history in 1851, as a crucial weapon in other countries’ innovation policy arsenals. They were used by countries like France in particular — which held an exhibition every few years from 1798 — as a means of catching up with Britain’s technology. This sounds strange nowadays, when the closest apparent parallels are vanity projects like the Millennium Experience, the recent controversial “Festival of Brexit” that ended up just being a bunch of temporary visitor attractions all over the country, and glitzy mega-events like the World’s Fairs. But the World’s Fairs, albeit notional successors to the Great Exhibition, have strayed very far from the original vision and purpose. They’re now more about celebration, infotainment and national branding, whereas the original industrial exhibitions had concrete economic aims.

Industrial exhibitions were originally much more akin to specialist industry fairs, with producers showing off their latest products, sort of combined with academic conferences, with scientists demonstrating their latest advances. Unlike modern industry fairs and conferences, however, which tend to be highly specialised, appealing to just a few people with niche interests, industrial exhibitions showed everything, altogether, all at once. They achieved a more widespread appeal to the public by being a gigantic event that was so much more than the sum of its parts — often helped along by the impressive edifices that housed them. The closest parallel is perhaps the Consumer Electronics Show, held since 1967 in the United States. But even this only focuses on particular categories of industry, and is largely catered towards attendees already interested in “tech”. Industrial exhibitions were like the CES, but for everything.

The point of all this, rather than just being an event for its own sake, was to actually improve the things on display. This happened in a number of ways, each of them complementing the other.

Concentration generated serendipity. By having such a vast variety of industries and discoveries presented at the same event, exhibitions greatly raised the chances of serendipitous discovery. A manufacturer exhibiting textiles might come across a new material from an unfamiliar region, prompting them to import it for the first time. An inventor working on a niche problem might see the scientific demonstration of a concept that had not occurred to them, providing a solution.

Comparison bred emulation. Producers, by seeing their competitors’ products physically alongside their own, would see how things could be done better. They could learn from their competitors, with the laggards being embarrassed into improving their products for next time. And this could take place at a much broader, country-wide level, revealing the places that were outperforming others and giving would-be reformers the evidence they needed to discover and adopt policies from elsewhere.

Exposure shattered complacency. The visiting public, as users and buyers of the things on display, would be exposed to superior products. This was especially effective for international exhibitions of industry, of which the Great Exhibition was the first, and simulated an effect that had only ever really been achieved through expensive foreign travel — by being exposed to things they hadn’t realised could already be so much better than what they were accustomed to, consumers raised their standards. They forced the usual suppliers of their products to either raise their game or lose out to foreign ones.