Imagine there’s a new $10,000 medication. Insurance companies are legally required to give it to people who really need it and would die without it. But they don’t want somebody who’s only a little bit sick demanding it as a “lifestyle” drug. In principle doctors are supposed to help with this, but doctors have no incentive to ever say no to their patients. If the insurance just sends the doctor a form asking “does this patient really need this medication?”, the doctor will always just check “yes” and send it back. Even if the form says in big red letters PLEASE ONLY SAY YES IF THERE IS AN IMPORTANT MEDICAL NEED, the doctor will still check “yes” more often than a rational central planner allocating scarce resources would like. And insurance companies are sometimes paranoid about refusing to do things doctors say are important, because sometimes the doctor was right and then they can get sued.

But imagine it takes the doctor an hour of painful phone calls to even get the right person from the insurance company on the line. Now there’s a cost involved. If your patient is going to die without the medication, you’ll probably groan and start making the phone calls. But if your patient doesn’t really need it, and you just wanted to approve it in order to be nice, now you might start having a heartfelt talk with your patient about the importance of trying less expensive medications before jumping right to the $10,000 one.

Organizations have a legal incentive not to deny people things, because the people involved can sue them. But they have an economic incentive not to say yes to every request they get. Seeing how much time and exasperation people are willing to put up with in order to get what they want is an elegant way of separating out the needy from the greedy if every other option is closed to you.

This story makes sense and would help explain why bureaucracy gets so bad, but I’m not sure it really fits the evidence. People complain a lot about bureaucracy in places like the Department of Motor Vehicles, but the DMV doesn’t lose anything by giving you a drivers license and isn’t interested in separating out people who really want licenses from people who only want them a little. If the DMV can be as bureaucratic as it is without any conspiratorial explanation, maybe everything is as bureaucratic as it is without any conspiratorial explanation.

Scott Alexander, “Bureaucracy as Active Ingredient”, Slate Star Codex, 2018-08-31.

January 13, 2021

QotD: Bureaucracy as a filter

January 5, 2021

QotD: Tax “loopholes”

… “loopholes” is a term most often used by people who don’t understand accounting or tax law, to complain about how somebody else used the existing laws created by congress to pay less than what that person thinks is “fair.” Regular people have heard the bullshit term loopholes tossed around so much that they start to believe that it is some magical easy button that rich guys can just push that makes it so they don’t have to pay taxes.

Nope. They’re just laws. These “loopholes” exist because at some point in time congress (both democrat and republican both!) decided that they wanted to promote some type of behavior or discourage some other behavior. So they basically put a reward into the law saying if you do this thing we like, you’ll pay less taxes! Or the opposite, congress wanted to discourage some behavior, so if you do that thing we don’t want, it will cost you more.

Both sides have done this forever, state and federal. We want you to drive electric cars so if you buy an electric car you get a tax break this year. YAY! Uh oh, we want you to stimulate the economy by buying this kind of machinery faster, so you have to depreciate your assets this other way or you’ll pay more! BOO! You get a discount for paying your employees health insurance, YAY! Oh, wait … Not that kind of health insurance. BOO!

So on and so forth, up and down, these perks come and go, all based upon whatever behavior congress is trying to promote at that time (or what favors they are doing for their friends). Why was mortgage interest deductible? Because at one point congress said “we really want people to own houses!” Even regular people have things that are considered “loopholes” to somebody.

So when the blue check mark journalism major (who probably dropped out of PoliSci because “there’s too much math”) declares that it is immoral that some rich dude didn’t pay his fair share because he used loopholes, those are basically a bunch of meaningless buzz words strung together to prey on the feelings of the gullible.

Larry Correia, “No, You Idiots. That’s Not How Taxes Work – An Accountant’s Guide To Why You Are A Gullible Moron”, Monster Hunter Nation, 2020-09-28.

December 26, 2020

Repost – The market failure of Christmas

Not to encourage miserliness and general miserability at Christmastime, but here’s a realistic take on the deadweight loss of Christmas gift-giving:

In strict economic terms, the most efficient gift is cold, hard cash, but exchanging equivalent sums of money lacks festive spirit and so people take their chance on the high street. This is where the market fails. Buyers have sub-optimal information about your wants and less incentive than you to maximise utility. They cannot always be sure that you do not already have the gift they have in mind, nor do they know if someone else is planning to give you the same thing. And since the joy is in the giving, they might be more interested in eliciting a fleeting sense of amusement when the present is opened than in providing lasting satisfaction. This is where Billy Bass comes in.

But note the reason for this inefficient spending. Resources are misallocated because one person has to decide what someone else wants without having the knowledge or incentive to spend as carefully as they would if buying for themselves. The market failure of Christmas is therefore an example of what happens when other people spend money on our behalf. The best person to buy things for you is you. Your friends and family might make a decent stab at it. Distant bureaucrats who have never met us — and who are spending other people’s money — perhaps can’t.

So when you open your presents next week and find yourself with another garish tie or an awful bottle of perfume, consider this: If your loved ones don’t know you well enough to make spending choices for you, what chance does the government have?

November 14, 2020

People are working from home? Gotta tax that!

I am … unimpressed … with this sudden urge to impose new taxes on people who are currently working from home (I was working from home before it was cool, so I clearly have an interest in this issue). In the Vancouver Sun, Colby Cosh discusses the “wisdom” of this latest proposed tax grab:

This is the first time I have heard this “obvious” idea in any setting, but maybe that’s me. Telecommuting has experienced rapid growth in the decades I’ve been doing it, but before the pandemic it remained more or less at barely detectable levels. [Deutsche Bank economist Luke] Templeman believes that, “Our economic system is not set up to cope with people who can disconnect themselves from face-to-face society. Those who can WFH receive direct and indirect financial benefits and they should be taxed in order to smooth the transition process for those who have been suddenly displaced.”

As Templeman describes it, you would have to have been a crazy idiot not to work from home all along if it were possible. “WFH offers direct financial savings on expenses such as travel, lunch, clothes and cleaning. … Then there are the intangible benefits of working from home, such as greater job security, convenience and flexibility. There is also the benefit of additional safety.”

This would be my own assessment, except for the gibberish parts (job security?), but you will notice that this is the opposite of [Bank of England chief economist Andy] Haldane’s October argument. Haldane thinks there are negative externalities and even net costs to the individual in working from home. Templeman thinks WFH is an inarguable optimum … and is hot as a $2 pistol to disincentivize it.

Does this make sense? Not economically. Templeman is making more of a moral argument that the great shift to WFH is permanent, for which there is some survey evidence, and that it is proper to tax the resulting windfall to ease the adjustment for affected sectors (businesses designed to cater to office workers, basically). This might persuade you, if like Templeman you mistake an “economic system” for the arrangements produced by that system; but if it does, wait till you see how he proposes to do it:

The tax will only apply outside the times when the government advises people to work from home (of course, the self-employed and those on low incomes can be excluded). The tax itself will be paid by the employer if it does not provide a worker with a permanent desk. If it does, and the staff member chooses to work from home, the employee will pay the tax out of their salary for each day they work from home. This can be audited by co-ordinating with company travel and technology systems.

There is more gibberish here, and at least one idea of Godzilla-scale terribleness — an incentive for employers to “provide” a desk for the purpose of shifting the WFH tax onto the employee. Undeterred, Templeman proposes for modelling purposes that the tax could be a flat five per cent of salary (which is also ridiculous if there’s a single eligibility threshold).

November 8, 2020

QotD: Tribal and post-tribal economies

… it was a problem of permitting, by and large. Portugal isn’t as bad, mind, nowhere near but in the seventies a lot of places were designated “green belts” everywhere, so that to build on them (and you had to build on them, or you were stymied in growth) you had to know who to bribe, and of course have the money to do it. This isn’t the only reason why favelas end up housing even the middle class. There’s a ton of other reasons, including but not limited to land ownership and property rights, and a shit-ton of stuff. But permitting is part of it.

This is because people don’t view their public posts as something they do to make society better/serve society or even do a job, but as a way to enrich themselves/benefit their friends/make it easier to make money in the future.

Everything, from truly shoddy workmanship to rushed, corner/cutting work, to outright corruption comes from viewing a job not as something you take pride in and work to do your best at, but from viewing a job as an opportunity to enrich yourself and your family while doing as little work as humanly possible. In fact in some societies, this is viewed as a duty. As someone in comments cited there are places in Africa where locals can’t run a shop, because all their relatives near and distant will expect to be given merchandise for free … or even money out of the till.

A lot of this is because the idea of the individual as independent of the tribe and the family is a very new thing in most of the world. We kind of have a head start on it because we are/are descended from those who left family and tribe behind.

[…]

Also in most of the world working for money is vaguely shameful. Particularly so if you’re working for someone else. […] And even here not only does that attitude persist, but it’s trying to make itself normal. Particularly in politics.

So, take pride in what you do, and do the best job you can. It’s not just important for you, it’s a building block of society. Do the best you can, and control as much as you can, so maybe you will have just reward which is an incentive to do better.

This way is civilization built. This way do things actually improve.

Sarah Hoyt, “BUILD!”, According to Hoyt, 2018-07-25.

November 4, 2020

The replication crisis in all fields is worse than you imagine

It may sound like a trivial issue, but it absolutely is not: scientific studies that can’t be replicated are worthless, yet our lives are often impacted by these failed studies, especially when politicans are guided by junk science results:

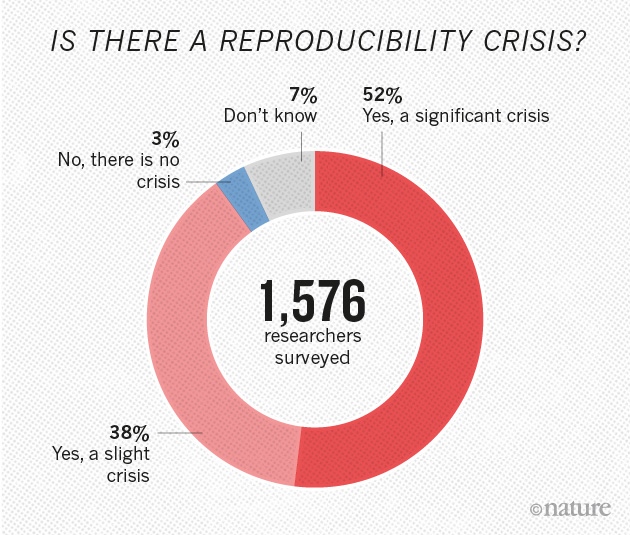

More than 70% of researchers have tried and failed to reproduce another scientist’s experiments, and more than half have failed to reproduce their own experiments. Those are some of the telling figures that emerged from Nature‘s survey of 1,576 researchers who took a brief online questionnaire on reproducibility in research.

The data reveal sometimes-contradictory attitudes towards reproducibility. Although 52% of those surveyed agree that there is a significant ‘crisis’ of reproducibility, less than 31% think that failure to reproduce published results means that the result is probably wrong, and most say that they still trust the published literature.

Data on how much of the scientific literature is reproducible are rare and generally bleak. The best-known analyses, from psychology and cancer biology, found rates of around 40% and 10%, respectively. Our survey respondents were more optimistic: 73% said that they think that at least half of the papers in their field can be trusted, with physicists and chemists generally showing the most confidence.

The results capture a confusing snapshot of attitudes around these issues, says Arturo Casadevall, a microbiologist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, Maryland. “At the current time there is no consensus on what reproducibility is or should be.” But just recognizing that is a step forward, he says. “The next step may be identifying what is the problem and to get a consensus.”

Failing to reproduce results is a rite of passage, says Marcus Munafo, a biological psychologist at the University of Bristol, UK, who has a long-standing interest in scientific reproducibility. When he was a student, he says, “I tried to replicate what looked simple from the literature, and wasn’t able to. Then I had a crisis of confidence, and then I learned that my experience wasn’t uncommon.”

The challenge is not to eliminate problems with reproducibility in published work. Being at the cutting edge of science means that sometimes results will not be robust, says Munafo. “We want to be discovering new things but not generating too many false leads.”

September 19, 2020

The perils and pitfalls of developing open source software

In The Diff, Byrne Hobart looks at the joys and pains-in-the-ass of open source software development:

“How university open debates and discussions introduced me to open source” by opensourceway is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

We’re in a strange in-between state where software is increasingly essential, the most important bits of it are built by dedicated volunteers, and there’s no great way to encourage them to a) keep doing this, and b) stay motivated as the work gets less and less fun. That was my main takeaway from Nadia Eghbal’s Working in Public, published this week.

The book is a tour of the open source phenomenon: who builds projects, how they get made and updated, and why. This is an important topic! Almost all of the software I use to write this newsletter is either built from open source products or relies on them: the text is composed in Emacs, on a computer running Linux; I browse the web using Chrome, which mostly consists of open-source Chromium code; my various i-devices run Unix-based OSes (iOS is not open-source, but there are as many open-source implementations of Unix as you want); etc. All of this software Just Works, and I don’t directly pay for any of it. Clearly there are some incentives at work, or it wouldn’t exist in the first place, but generally the more complex an activity is, the harder it is to coordinate without pricing signals. Somehow, open-source projects don’t fall victim to this.

As Working in Public shows, they do face a demoralizing lifecycle. When a project starts, it’s one coder trying to solve a problem they face, and trying to solve it their way. Sometimes, there’s a good reason their preferred solution doesn’t exist yet, and the project languishes. Sometimes, the project catches on, acquiring new users, new contributors, and new bug reports and feature requests.

[…]

Software projects go through this exact cycle: at first, they’re mostly producing and building on “software capital,” code that executes the underlying logic of the process. Over time, more of the work involves integration and compatibility, and as all the easy edge cases get identified, the remaining bugs are a) disproportionately rare (or they would have been spotted by now) and b) disproportionately hard to fix (because they have to be the result of a rare and thus complicated confluence of circumstances). So, over time, a software project falls into the Baumol Trap, where high productivity in the fun stuff produces more and more un-fun work where productivity gains are hard to come by.

This is depressing for project creators. Early on, they have the triumphant experience of building exactly what they want, and solving their nagging problem. And the result is that they’re cleaning up after a bunch of requests from people who are either annoyed that it doesn’t work for them or have unsolicited feedback on how it ought to work. No wonder Linus Torvalds gets so mad. Running a successful open source project is just Good Will Hunting in reverse, where you start out as a respected genius and end up being a janitor who gets into fights.

Emphasis mine, not in the original article.

H/T to Colby Cosh for sharing the link.

September 18, 2020

From innovation to absolutism — English inventors and the Divine Right of Kings

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes looks at how innovations during the late Tudor and Stuart eras sometimes bolstered the monarchy in its financial battles with Parliament (which, in turn, eventually led to actual battles during the English Civil War):

King Charles I and Prince Rupert before the Battle of Naseby 14th June 1645 during the English Civil War.

19th century artist unknown, from Wikimedia Commons.

The various schemes that innovators proposed — from finding a northeast passage to China, to starting a brass industry, to colonising Virginia, or boosting the fish industry by importing Dutch salt-making methods — all promised to benefit the public. They were to support the “common weal”, or commonwealth. And to a certain extent, many projects did. The historian Joan Thirsk did much pioneering work in the 1970s to trace the impact of various technological or commercial projects, revealing that even something as mundane as growing woad, for its blue dye, could have a dramatic impact on local economies. With woad, the income of an ordinary farm labouring household might be almost doubled, for four months in the year, by employing women and children. In the late 1580s, the 5,000 or so acres converted to woad-growing in the south of England likely employed about 20,000 people. That may seem small today, but at a time when the population of a typical market town was a paltry 800 people, even a few hundred acres of woad being cultivated here or there might draw in workers from across the whole region. In the mid-sixteenth century, even the entire population of London had only been about 50-70,000. As Thirsk discovered, innovative projectors also sometimes fulfilled their other public-spirited promises, for example by creating domestic substitutes for costly imported goods, or securing the supplies of strategic resources.

But the ideal of benefiting the commonwealth could also, all too frequently, be elided with serving the interests of the Crown. Projectors might promise the monarch a direct share of an invention’s profits, or that a stimulated industry would result in higher income from tariffs or excise taxes. Increasingly, they proposed schemes that were almost entirely focused on maximising state revenue, with little evidence of new technology. They identified “abuses” in certain industries — at this remove, it’s difficult to tell if these justifications were real — and asked for monopolies over them in order to “regulate” them, then making money by selling licences. Last week I mentioned patents over alehouses, and on playing cards. They also offered to increase the income from the Crown’s property, for example by finding so-called “concealed lands” — lands that had been seized during the Reformation, but which through local resistance or corruption had ostensibly not been paying their proper rents. The projectors would take their share of the money they identified as “missing”. And they proposed enforcing laws, especially if the punishments involved levying fines or confiscating property. The projectors offered to find the lawbreakers and prosecute them, after which they’d take their share of the financial punishments.

Projectors thus came to present themselves as state revenue-raisers and enforcers, circumventing all of the traditional constraints on the monarch’s money and power. They provided an alternative to Parliaments, as well as to city corporations and guilds, in raising money and propagating their rule. Taking it a step further, projectors offered the tantalising possibility that kings like James I and Charles I might rule through proclamation and patents alone, without having to answer to anybody. They thus experimented with absolutism for much of 1610-40, only occasionally being forced to call Parliament for as briefly as possible when the pressing financial demands of war intervened.

In the process, with the growing multitude of projects — a few bringing technological advancement, but many merely lining the pockets of courtier and king — the designation “projector” became mud. It was as if, today, the Queen were to use her prerogative to grant a few of her courtiers monopolies on collecting all traffic fines, or litter penalties, to be rewarded solely on commission. Or if she were to award an unscrupulous private company the right to award all alcohol-selling licences (perhaps on the basis that underage drinking was becoming common). The country would soon be awash with hidden speed cameras and incognito litter wardens, and the price of alcohol would go through the roof. The people responsible would not be popular. A recent book by economic historian Koji Yamamoto meticulously charts the changing public perceptions of projects, describing the ways in which innovators then struggled, for decades, to regain the public’s trust.

August 13, 2020

QotD: The discovery of anaesthesia and antisepsis

The first demonstration of the ether gas was performed at Massachusetts General Hospital in October, 1846, by a Boston dentist, William T. G. Morton. For the first time, surgical operations could be performed painlessly. Within two months, the invention was known and being applied in every capital of Europe, and in little more time it became commonplace internationally. The number of surgical operations vastly increased, as it was no longer necessary to hold patients down, and act very quickly.

Joseph Lister first used carbolic acid (phenol) to perform sterile surgery at the Glasgow Royal Infirmary, in August, 1865. This would have the effect of vastly increasing the survival rate from these now commonplace surgical operations. But the news took years to circulate, and by the twentieth century surgeons were still working with infected equipment in filthy environments. Indeed, I have read accounts of the horrors of battlefield medicine in the First World War: men with survivable injuries, lost by the hundred thousands from ignorant, unnecessarily unhygienic medical procedures.

As Dr Gawande points out — in passing — both advances made life easier on patients. But the second saved lives on a — vastly — greater scale. The first was unique, in making life easier for doctors, who no longer had to operate on screaming, writhing customers. This also, incidentally, hugely increased their trade, and thus their income. Washing up, effectively, only added nuisance.

I already knew this history — my mommy was a ward matron, after all — but until the comparison was spelt out, the full significance was lost on me. I had read the “official” versions in several standard medical histories. They assume the slow spread of antisepsis was a problem of communications. Gentle reader will note that this is a lie. Methods of communication did not slow in the generation between the two inventions.

David Warren, “Heaven, Hell, & Alder Hey”, Essays in idleness, 2018-05-09.

July 28, 2020

QotD: Incentives and opportunity costs

The first and most important thing in all economics is that incentives matter. If you can grasp that and also get to grips with the second, that there are always opportunity costs, then you’re going to be doing better than 90% of the economics profession itself. But do remember that incentives matter, incentives really, really, matter. Changes in tax law have stopped people from dying for example.

No, really, there was one of those natural experiments, when inheritance tax laws changed at the end of the year. There was a definite blip downwards in the death rate of people rich enough to pay inheritance tax at the end of the year, a corresponding one upwards again as the new, lower, rates came into effect in January. Incentives really, really, matter.

Tim Worstall, “What’s The Over And Under On Tesla’s 200,000th Car Being Delivered On July 1?”, Continental Telegraph, 2019-05-03.

July 26, 2020

QotD: Bureaucracy at its heart

Nassim Nicholas Taleb summed up in a simple aphorism what most of us instinctively know about bureaucracies:

Bureaucracy is a construction designed to maximize the distance between a decision-maker and the risks of the decision.

When something goes wrong, the bureaucrats play the blame-shifting game. Musical chairs will begin, and some poor fool will be stuck without a chair. When something goes right, of course, executive management will take credit. Your job as a bureaucrat is to be an implicitly political creature; to make your boss look good and, for yourself, to evade blame.

Bureaucracies become much worse when they are divorced from the profit motive. At least a large corporation must theoretically serve its customers in some positive manner, or they won’t remain in business for long. So while the internal politics of a large corporation are likely to suck like a Hoover, the external face of the company is often still somewhat pleasant for the customer.

With government bureaucracy, even that small consolation is lost. Go to the DMV, or any large government bureau. Long lines, smelly “customers”, and agents with extremely unpleasant attitudes abound. The motive is not to serve citizens well, or even to serve them quickly, but rather to meet the bare minimum necessary to avoid blame — and sometimes not even that.

Thales, “Bureacracy is Designed to Suck”, The Declination, 2018-05-02.

July 15, 2020

Donald Shoup, the “Sir Isaac Newton of parking” or an “‘academic bottom-feeder’ who found a wonderful, rich ecological niche down there in the depths”

Colby Cosh, after taunting Ontarians yet again over our just-barely-past-Prohibition views on alcohol in public places, goes on to praise the work of UCLA economist Donald Shoup and his insights into the economics of parking:

“Parking meter FAIL” by kingdesmond1337 is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Parking — boring topic, ain’t it? Shoup latched onto it as a young-ish man because he was a follower of Henry George (1839-1897), the intriguing “single tax” economic theorist of the 19th century. George favoured a tax on the unimproved value of land parcels as a way of socializing pure rent (the value earned from occupying a mere location) and encouraging development. It is a concept that many economists still like, although it is potentially difficult to apply at scale. The widely used concept of tax increment financing is one example of Georgism in practice.

Shoup started out trying to fit parking spaces into the Georgist picture, but the boring topic was so underexamined that he found himself having to build a general theory of parking. He quantified the relationship between parking and traffic, finding that people “cruising” for parking spots were more destructive than anyone had imagined, and he inspired waves of research into the hidden market values of parking spots, which are rarely bought or sold in their own right. He happily describes himself as an “academic bottom-feeder” who found a wonderful, rich ecological niche down there in the depths.

Shoup has spent decades travelling the world and preaching against the concept of free parking, often meeting with bad-tempered resistance. Nevertheless, he has made a lot of headway in the world of urban planning. Any economist can see immediately how bundling a “free” parking space with an apartment or a job might be inefficient. The renter or homeowner has to pay a hidden extra cost for an amenity he might not choose to use, and the commuter is being given an incentive to drive to work — an incentive whose cash value he might prefer to keep. Shoup soon found, on empirical investigation, that most urban parking lots show signs of less-than-optimum use.

[…]

Of course, too little parking is as much of an efficiency problem as too much, which is why Shoup and his followers want parking to be priced wherever possible: if more is really needed, let a market create it. (To my eyes he has at least as much Hayek in him as Henry George.) In the era of Uber and smartphones, it is a lot easier to imagine a fully Shoupista world in which prices for parking spots update in real time and drivers look up prices at or near their destination before setting out.

May 21, 2020

The Great Exhibition of 1851 also served (for some) as the 19th century equivalent of the “Missile Gap” controversy

In the latest edition of his Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes discusses the changing role of the British government and how the Great Exhibition was also useful as subtle domestic propaganda for a more active role for government in the British economy:

The Crystal Palace from the northeast during the Great Exhibition of 1851, image from the 1852 book Dickinsons’ comprehensive pictures of the Great Exhibition of 1851

Wikimedia Commons.

… a whole new opportunity for reform was provided by the Great Exhibition of 1851. As I explained in the previous newsletter, an international exhibition of industry functioned as an audit of the world’s industries. It, and its successors, the world’s fairs, gave some indication of how Britain stood relative to rival nations, especially France, Prussia, and the United States. And whereas some people saw the Great Exhibition as a clear mark of Britain’s superiority, for would-be reformers it was a chance to expose worrying weaknesses. Thus, Henry Cole and the other original organisers of the exhibition at the Society of Arts exacerbated fears of Britain’s impending decline, giving them an excuse to create the systems they desired.

They identified two areas of worry: science and design. Britain of course had many eminent scientists and artists — some of the best in the world — but other countries seemed to have become better at diffusing scientific training and superior taste throughout the workforce as a whole. Design skills were an issue because France appeared to be catching up with Britain when it came to the mechanisation of industry; if it caught up on machinery while maintaining its lead in fashion, then Britain would not be able to compete. And scientific training appeared more useful than ever, with the latest scientific advances “influencing production to an extent never before dreamt of”. Visitors to the Great Exhibition had marvelled at the recent inventions of artificial dyes, a method of processing beetroot sugar, and the latest improvements to photography and the electric telegraph. Thus, for Britain to maintain its lead, it would need to improve the education of its workers.

The reformers’ scare tactics worked. The aftermath of the Great Exhibition saw the creation of a government Department of Science and Art under the direction of Henry Cole, who in turn oversaw the agglomeration of various museums, design schools, and other cultural institutions to what is now the “Museum Mile” in South Kensington. (Curiously, the area was originally called Brompton, but when Cole opened a museum of design and industry there, he named it the South Kensington Museum. Kensington was a much more aristocratic area nearby, though it had no “south” at the time. The museum evolved, rather complicatedly, into what is now the Victoria & Albert Museum. But unlike so many top-down area re-brands, the name South Kensington stuck.)

And that was just the beginning. Cole and his allies then oversaw a dramatic expansion of the state into education, largely through the use of examinations. Although state-funding for education had initially centred on building new schools, getting any more involved was a highly contentious issue. Most schools were controlled and funded by religious organisations, but were split between the established Anglican church and dissenters. When the government first became involved in schools, it was thus bitterly opposed by many dissenters as they feared that their children might become indoctrinated to Anglicanism. And naturally, the government could not teach dissenting religions. Yet the proposed compromise of teaching no religion at all was unacceptable to both sides. Schools were crucial, the groups believed, to keeping religion alive.

So the utilitarians came up with a workaround. Rather than getting the state too involved directly in managing the schools themselves, it would instead influence the curriculum. By holding examinations, and then paying teachers based on the outcomes of the tests, they could incentivise the teaching of certain subjects and leave the schools free to teach whatever religious beliefs they pleased. Indeed, by diverting more and more time towards teaching particular subjects, the reformers saw it as a secularising blow “against parsonic influence”. The tactic was initially applied to adult education. The Society of Arts would first trial out examinations without payments, to test their viability. Then Cole would have his department take over the examinations, first for drawing, and later for science, using his budget to fund payment-by-results. The effects were dramatic. The Society’s relatively popular examinations in chemistry, for example, rarely had more than a hundred candidates a year. But when the department instituted its payments, it soon drew in thousands. By 1862, when the government wanted to improve the teaching of reading, writing, and arithmetic in schools, they adopted Cole’s suggestion that they also use payment-by-results.

May 18, 2020

Safetyism

Safetyism is a disposition that has been gaining strength for decades and is having a triumphal moment just now because of the virus. Public health, one of many institutions that speak on behalf of safety, has claimed authority to sweep aside whole domains of human activity as reckless, and therefore illegitimate.

I suspect the ease with which we have lately accepted the authority of health experts to reshape the contours of our common life is due to the fact that safetyism has largely displaced other moral sensibilities that might offer some resistance. At the level of sentiment, there appears to be a feedback loop wherein the safer we become, the more intolerable any remaining risk appears. At the level of bureaucratic grasping, we can note that emergency powers are seldom relinquished once the emergency has passed. Together, these dynamics make up a kind of ratchet mechanism that moves in only one direction, tightening against the human spirit.

Acquiescence in this appears to be most prevalent among the meritocrats who staff the managerial layer of society. Deferring to expert authority is a habit inculcated in the “knowledge economy”, naturally enough; the basic currency of this economy is epistemic prestige.

Among those who work in the economy of things, on the other hand, you see greater skepticism toward experts (whether they make their claim on epistemic or moral grounds) and less readiness to accept the adjustment of social norms by fiat – whether that means using new pronouns or wearing surgical masks. I am regularly in welding supply stores, auto parts stores and other light-industry venues. Nobody is wearing masks in these places. They are very small businesses: an environment largely free of the moral fashions and corresponding knowledge claims that set the tone in large organisations. There is no HR in a welding shop.

A pandemic is a deadly serious business. But we would do well to remember that bureaucracies have their own interests, quite apart from the public interest that is their official brief and warrant. They are very much in the business of tending and feeding the narratives that justify their existence. Further, given the way bureaucracies must compete for funding from the legislature, each must make a maximal case for the urgency of its mission, hence the necessity of its expansion, like a shark that must keep moving or die. It is clearer now than it was a few months ago that this imperative of expansion puts government authority in symbiosis with the morality of safetyism, which similarly admits no limit to its expanding imperium. The result is a moral-epistemic apparatus in which experts are to rule over citizens conceived as fragile incompetents.

But what if this apparatus were revealed to be not very serious about safety, the very ideal that underwrites its authority? What then?

May 5, 2020

The perverse incentives of the Wuhan Coronavirus outbreak

David Warren has clearly taken his cynical pills today:

The daily count of deaths from the Red Chinese Batflu is among the prized, scare-mongering features of our mass media. I am among those who consider these numbers to be significantly overstated, for a reason that Nikolai Gogol would understand. Each corpse is worth cash to some public authority, usually from a higher authority; and as always, finally from the taxpayers. Each also saves money for government programmes, that can be reallocated to the purchase of new votes. As the corpse providers from this virus are very old, and suffering from other life-threatening conditions, in almost every case, this statistical inflation is easy to perform. Death certificates are issued for any who died with “Covid-19,” whether or not they died from it, and more are then added of those who were never tested. Anything respiratory will do. It’s all judgement calls — on which side of the bread is buttered.

Compare if you will the Hong Kong Flu of 1968 and 1969. I was just reading a memoir, from down that memory hole. The death toll was actually higher then, than ours is now, and from within a smaller population; the victims included children and the young. Yet there were no interruptions in economic life; no public emergency theatricals; and at the height of the second wave of that scourge, we had events like Woodstock. (Those were the days, my friend.)

A neat way to correct for all our “judgement calls” might be to look at overall death rates, and see if they have risen or fallen. It is too early to get a clear view, but soon it may be too late, for vested interests will have tampered with them. All my life I have been learning to trust statistics, less — especially from those who dress in labcoats and affect that earnest look. Sometimes an exception must be considered, however. An unpredictable minority may be honest; some others might get numbers right by mistake.