The struggle for power between the Spanish Republican parties is an unhappy, far-off thing which I have no wish to revive at this date. I only mention it in order to say: believe nothing, or next to nothing, of what you read about internal affairs on the Government side. It is all, from whatever source, party propaganda — that is to say, lies. The broad truth about the war is simple enough. The Spanish bourgeoisie saw their chance of crushing the labour movement, and took it, aided by the Nazis and by the forces of reaction all over the world. It is doubtful whether more than that will ever be established.

I remember saying once to Arthur Koestler, ‘History stopped in 1936’, at which he nodded in immediate understanding. We were both thinking of totalitarianism in general, but more particularly of the Spanish civil war. Early in life I have noticed that no event is ever correctly reported in a newspaper, but in Spain, for the first time, I saw newspaper reports which did not bear any relation to the facts, not even the relationship which is implied in an ordinary lie. I saw great battles reported where there had been no fighting, and complete silence where hundreds of men had been killed. I saw troops who had fought bravely denounced as cowards and traitors, and others who had never seen a shot fired hailed as the heroes of imaginary victories; and I saw newspapers in London retailing these lies and eager intellectuals building emotional superstructures over events that had never happened. I saw, in fact, history being written not in terms of what happened but of what ought to have happened according to various ‘party lines’. Yet in a way, horrible as all this was, it was unimportant. It concerned secondary issues — namely, the struggle for power between the Comintern and the Spanish left-wing parties, and the efforts of the Russian Government to prevent revolution in Spain. But the broad picture of the war which the Spanish Government presented to the world was not untruthful. The main issues were what it said they were. But as for the Fascists and their backers, how could they come even as near to the truth as that? How could they possibly mention their real aims? Their version of the war was pure fantasy, and in the circumstances it could not have been otherwise.

The only propaganda line open to the Nazis and Fascists was to represent themselves as Christian patriots saving Spain from a Russian dictatorship. This involved pretending that life in Government Spain was just one long massacre (vide the Catholic Herald or the Daily Mail — but these were child’s play compared with the Continental Fascist press), and it involved immensely exaggerating the scale of Russian intervention. Out of the huge pyramid of lies which the Catholic and reactionary press all over the world built up, let me take just one point — the presence in Spain of a Russian army. Devout Franco partisans all believed in this; estimates of its strength went as high as half a million. Now, there was no Russian army in Spain. There may have been a handful of airmen and other technicians, a few hundred at the most, but an army there was not. Some thousands of foreigners who fought in Spain, not to mention millions of Spaniards, were witnesses of this. Well, their testimony made no impression at all upon the Franco propagandists, not one of whom had set foot in Government Spain. Simultaneously these people refused utterly to admit the fact of German or Italian intervention at the same time as the Germany and Italian press were openly boasting about the exploits of their’ legionaries’. I have chosen to mention only one point, but in fact the whole of Fascist propaganda about the war was on this level.

This kind of thing is frightening to me, because it often gives me the feeling that the very concept of objective truth is fading out of the world. After all, the chances are that those lies, or at any rate similar lies, will pass into history. How will the history of the Spanish war be written? If Franco remains in power his nominees will write the history books, and (to stick to my chosen point) that Russian army which never existed will become historical fact, and schoolchildren will learn about it generations hence. But suppose Fascism is finally defeated and some kind of democratic government restored in Spain in the fairly near future; even then, how is the history of the war to be written? What kind of records will Franco have left behind him? Suppose even that the records kept on the Government side are recoverable — even so, how is a true history of the war to be written? For, as I have pointed out already, the Government, also dealt extensively in lies. From the anti-Fascist angle one could write a broadly truthful history of the war, but it would be a partisan history, unreliable on every minor point. Yet, after all, some kind of history will be written, and after those who actually remember the war are dead, it will be universally accepted. So for all practical purposes the lie will have become truth.

George Orwell, “Looking back on the Spanish War”, New Road, 1943 (republished in England, Your England and Other Essays, 1953).

April 6, 2019

QotD: Truth and propaganda in the Spanish Civil War

March 24, 2019

QotD: France and the Nazi Final Solution

Less happy is the story of France. The Germans realized that the Vichy French were attached to assimilated French Jews, so they started by demanding only those foreign Jews who had come to France as refugees. There were a hundred thousand of these, and Marshal Petain of France said that they had “always been a problem” and he was glad to have “an opportunity to get rid of them” (in his defense, he was under the impression that Jews sent to Germany would be “resettled in the East”). After this had been going on for a while, Eichmann figured that the French were on his side, and asked for permission to take the native French Jews as well. The French, having sent tens of thousands of stateless Jews to the concentration camps, were suddenly outraged that the Nazis would dare lift a finger against French Jews, and shut down the entire deportation program. I am sure the French count this as a moral victory nowadays, though it’s a very selective sort of morality.

Scott Alexander, “Book review: Eichmann in Jerusalem”, Slate Star Codex, 2017-01-30.

March 15, 2019

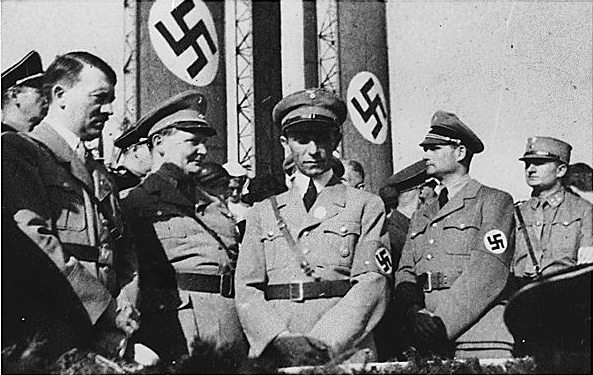

Big business and the rise of Hitler and the Nazi party

Alec Stapp reviews a new book by Tim Wu which contends that big business in the US is going to enable the rise of fascism just as it did in Germany in the 1930s … except that wasn’t how it happened in the Weimar Republic:

The recent increase in economic concentration and monopoly power make the United States “ripe for dictatorship,” claims Columbia law professor Tim Wu in his new book, The Curse of Bigness. With the release of Senator Elizabeth Warren’s proposal to “break up” technology companies like Amazon and Google, fear of bigness is clearly on the rise. Professor Wu’s book adds a new dimension to that fear, arguing that cooperation between political and economic power are “closely linked to the rise of fascism” because “the monopolist and the dictator tend to have overlapping interests.” Economist Hal Singer calls this the book’s “biggest innovation.”

The argument is provocative, but wrong. As I show below, the claim that big business contributed to the rise of the Nazi Party is simply inconsistent with the consensus among German historians. While there is some evidence industrial concentration contributed in Hitler’s ability to consolidate power after he was appointed chancellor in 1933, there is no evidence monopolists financed Hitler’s rise to power, and ample evidence showing industry leaders opposed his ascent.

Thomas Childers, a professor of history at the University of Pennsylvania, calls the idea that Hitler was bankrolled by big corporate donors a “persistent myth.” This, among myriad other reasons, should give us pause before comparing 1930s Germany to the present-day United States. If fascism does come to the United States, big business won’t be to blame.

[…]

In the run-up to the presidential election in the spring of 1932, Hitler gave a speech to “a gathering of some 650 members of the Düsseldorf Industry Club in the grand ballroom of Düsseldorf’s Park Hotel.” British historian Sir Ian Kershaw recounts the event in Hitler: A Biography (p. 224):

Hitler’s much publicized address … did nothing, despite the later claims of Nazi propaganda, to alter the skeptical stance of big business. The response to his speech was mixed. But many were disappointed that he had nothing new to say, avoiding all detailed economic issues by taking refuge in his well-trodden political panacea for all ills. And there were indications that workers in the party were not altogether happy at their leader fraternizing with industrial leaders. Intensified anti-capitalist rhetoric, which Hitler was powerless to quell, worried the business community as much as ever. During the presidential campaigns of spring 1932, most business leaders stayed firmly behind Hindenburg, and did not favour Hitler … The NSDAP’s funding continued before the ‘seizure of power’ to come overwhelmingly from the dues of its own members and the entrance fees to party meetings. Such financing as came from fellow-travellers in big business accrued more to the benefit of individual Nazi leaders than the party as a whole. Göring, needing a vast income to cater for his outsized appetite for high living and material luxury, quite especially benefited from such largesse. Thyssen in particular gave him generous subsidies, which Göring — given to greeting visitors to his splendrously adorned Berlin apartment dressed in a red toga and pointed slippers, looking like a sultan in a harem — found no difficulty in spending on a lavish lifestyle.

As Ralph Raico, a professor of history at Buffalo State College, points out, the aim of these “relatively minor subsidies” to particular Nazis “was to assure (the donors) of ‘friends’ in positions of power, should the Nazis enter the state apparatus.” In Hitler: Ascent, 1889-1939, German historian and journalist Volker Ullrich details the extent of the industrialists’ support for center-right parties during the time of the Düsseldorf speech (p. 292):

[T]he American historian Henry A. Turner and others following in his footsteps have corrected this outmoded narrative about the relationship between National Socialism and major German industry. By no means had the entire economic elite of the Ruhr Valley attended Hitler’s speech… The crowd’s reaction to Hitler was also by no means as positive as (Nazi Press Chief Otto) Dietrich’s report had its readers believe. When Thyssen concluded his short word of thanks with the words “Heil, Herr Hitler,” most of those in attendance found the gesture embarrassing. Hitler’s speech also did little to increase major industrialists’ generosity when it came to party donations. Even Dietrich himself admitted as much in his far more sober memoirs from 1955: “At the ballroom’s exit, we asked for donations, but all we got were some well-meant but insignificant sums. Above and beyond that there can be no talk of ‘big business’ or ‘heavy industry’ significantly supporting, to say nothing of financing, Hitler’s political struggle.” On the contrary, in the spring 1932 Reich presidential elections, prominent representatives of industry like Krupp and Duisberg came out in support of Hindenburg and donated several million marks to his campaign.

The period immediately following Hitler’s speech to the Düsseldorf Industry Club was similarly fruitless for fundraising, as Richard J. Evans, a professor of history at the University of Cambridge, describes in The Coming of the Third Reich (p. 245):

Neither Hitler nor anyone else followed up the occasion with a fund-raising campaign amongst the captains of industry. Indeed, parts of the Nazi press continued to attack trusts and monopolies after the event, while other Nazis attempted to win votes in another quarter by championing workers’ rights. When the Communist Party’s newspapers portrayed the meeting in conspiratorial terms, as a demonstration of the fact that Nazism was the creature of big business, the Nazis went out of their way to deny this, printing sections of the speech as proof of Hitler’s independence from capital. The result of all this was that business proved not much more willing to finance the Nazi Party than it had been before.

Hitler lost the spring 1932 presidential election to Hindenburg. But the Nazi party achieved a plurality of seats in parliament for the first time in the July 1932 elections. Unable to form a government without Nazi cooperation after yet another round of elections in November 1932, Hindenburg appointed Hitler chancellor on January 30, 1933. With Hitler now in power, things changed.

In a 2014 review, Larry Schweikart wrote:

Still, more than a few voices critical of such historical hanky-panky have been raised. Perhaps the most influential is that of Henry A. Turner, Jr., who has provided an accurate and verifiable history of the Weimar period in his German Big Business and the Rise of Hitler. Turner sensibly avoids class struggle as a theme and simply asks if big business liked Hitler. Did business leaders support him? Did they give him money? Turner concludes that they did not. Only “through gross distortion can big business be accorded a crucial, or even major, role in the downfall of the Republic” (p. 340). Turner claims that bias “appears over and over again in treatments of the political role of big business even by otherwise scrupulous historians” (p. 350).

In his own examination of the evidence, Turner looked at the correspondence of German business leaders, minutes of their meetings, and their contributions. While it might be reassuring for some to think that Hitler came to power through the financial support of a few evil businessmen, the facts are that most of the Nazis’ money came from the German people. Turner carefully discusses Hitler’s policy stances toward business. Hitler was always wary of alienating the businessmen, but his failure to present a clear, procapitalistic economic program made the corporate leaders all the more leery of him. Modern Marxists, quite naturally, would like to implicate capitalism in the Holocaust. But, of course, Hitler’s themes were those of Stalin and, in our own day, Gorbachev. Nazism, as Turner suggests but never makes sufficiently clear, resembled Marxism in many ways, including Jew-hatred and hostility to the individual. In any case, Turner’s book has completely refuted the accepted notions that German corporations supported Hitler.

H/T to Colby Cosh for the initial link.

March 14, 2019

How Hollywood Helped Hitler | Between 2 Wars | 1926 Part 2 of 2

TimeGhost History

Published on 13 Mar 2019The rise of the media superstar and the rise of Naziism had a lot to do with each other. The early death of one of the first media superstars, Rudolph Valentino in 1926 shows us exactly how and why.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Hosted by: Indy Neidell

Directed by: Astrid Deinhard

Written by: Spartacus Olsson

Produced by: Astrid Deinhard

Executive Producers: Bodo Rittenauer, Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson

Creative Producer: Joram Appel

Post Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Edited by: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: Spartacus OlssonColorized Pictures by Olga Shirnina

https://klimbim2014.wordpress.comVideo Archive by Screenocean/Reuters http://www.screenocean.com

A TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

From the comments:

TimeGhost History

2 hours ago

After a week of radio silence, we’re back with another Between Two Wars episodes. We’re continuing in the spirit of where we left off, and enter the crazy and hyped-up world of superstars. We hope that you like our video! If you do, please consider supporting us on Patreon or via our website timeghost.tv. We are still only just managing to cover the minimum that is required to produce this content. Every dollar truly counts. -> https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

January 18, 2019

January 10, 2019

QotD: Pacifism

The majority of pacifists either belong to obscure religious sects or are simply humanitarians who object to the taking of life and prefer not to follow their thoughts beyond that point. But there is a minority of intellectual pacifists whose real though unadmitted motive appears to be hatred of western democracy and admiration of totalitarianism. Pacifist propaganda usually boils down to saying that one side is as bad as the other, but if one looks closely at the writings of younger intellectual pacifists, one finds that they do not by any means express impartial disapproval but are directed almost entirely against Britain and the United States. Moreover they do not as a rule condemn violence as such, but only violence used in defence of western countries. The Russians, unlike the British, are not blamed for defending themselves by warlike means, and indeed all pacifist propaganda of this type avoids mention of Russia or China. It is not claimed, again, that the Indians should abjure violence in their struggle against the British. Pacifist literature abounds with equivocal remarks which, if they mean anything, appear to mean that statesmen of the type of Hitler are preferable to those of the type of Churchill, and that violence is perhaps excusable if it is violent enough. After the fall of France, the French pacifists, faced by a real choice which their English colleagues have not had to make, mostly went over to the Nazis, and in England there appears to have been some small overlap of membership between the Peace Pledge Union and the Blackshirts. Pacifist writers have written in praise of Carlyle, one of the intellectual fathers of Fascism. All in all it is difficult not to feel that pacifism, as it appears among a section of the intelligentsia, is secretly inspired by an admiration for power and successful cruelty. The mistake was made of pinning this emotion to Hitler, but it could easily be retransfered.

George Orwell, “Notes on Nationalism”, Polemic, 1945-05.

December 16, 2018

QotD: Transferring nationalist passions

The intensity with which they are held does not prevent nationalist loyalties from being transferable. To begin with, […] they can be and often are fastened up on some foreign country. One quite commonly finds that great national leaders, or the founders of nationalist movements, do not even belong to the country they have glorified. Sometimes they are outright foreigners, or more often they come from peripheral areas where nationality is doubtful. Examples are Stalin, Hitler, Napoleon, de Valera, Disraeli, Poincare, Beaverbrook. The Pan-German movement was in part the creation of an Englishman, Houston Chamberlain. For the past fifty or a hundred years, transferred nationalism has been a common phenomenon among literary intellectuals. With Lafcadio Hearne the transference was to Japan, with Carlyle and many others of his time to Germany, and in our own age it is usually to Russia. But the peculiarly interesting fact is that re-transference is also possible. A country or other unit which has been worshipped for years may suddenly become detestable, and some other object of affection may take its place with almost no interval. In the first version of H. G. Wells’s Outline of History, and others of his writings about that time, one finds the United States praised almost as extravagantly as Russia is praised by Communists today: yet within a few years this uncritical admiration had turned into hostility. The bigoted Communist who changes in a space of weeks, or even days, into an equally bigoted Trotskyist is a common spectacle. In continental Europe Fascist movements were largely recruited from among Communists, and the opposite process may well happen within the next few years. What remains constant in the nationalist is his state of mind: the object of his feelings is changeable, and may be imaginary.

But for an intellectual, transference has an important function […]. It makes it possible for him to be much more nationalistic — more vulgar, more silly, more malignant, more dishonest — that he could ever be on behalf of his native country, or any unit of which he had real knowledge. When one sees the slavish or boastful rubbish that is written about Stalin, the Red Army, etc. by fairly intelligent and sensitive people, one realises that this is only possible because some kind of dislocation has taken place. In societies such as ours, it is unusual for anyone describable as an intellectual to feel a very deep attachment to his own country. Public opinion — that is, the section of public opinion of which he as an intellectual is aware — will not allow him to do so. Most of the people surrounding him are sceptical and disaffected, and he may adopt the same attitude from imitativeness or sheer cowardice: in that case he will have abandoned the form of nationalism that lies nearest to hand without getting any closer to a genuinely internationalist outlook. He still feels the need for a Fatherland, and it is natural to look for one somewhere abroad. Having found it, he can wallow unrestrainedly in exactly those emotions from which he believes that he has emancipated himself. God, the King, the Empire, the Union Jack — all the overthrown idols can reappear under different names, and because they are not recognised for what they are they can be worshipped with a good conscience. Transferred nationalism, like the use of scapegoats, is a way of attaining salvation without altering one’s conduct.

George Orwell, “Notes on Nationalism”, Polemic, 1945-05.

November 13, 2018

A Kristallnacht album

9 November, 1938. The Germans called it Kristallnacht, the “Night of Broken Glass”, Reichspogromnacht or simply Pogromnacht. Elisheva Avital tells the story of a photo album from that terrible event that came into her grandfather’s possession at some point during World War 2:

November 10, 2018

Hitler’s Beer Hall Disaster I BETWEEN 2 WARS I 1923 Part 1 of 2

TimeGhost History

Published on 10 Nov 2018When Germany spirals into hyperinflation and the French occupy the Ruhr, Adolf Hitler and Erich Ludendorff make a grab for power.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Hosted by: Indy Neidell

Written and directed by: Spartacus Olsson

Writing and Research Contributed by: Rune V. Hartvig

Produced by: Astrid Deinhard

Executive Producers: Bodo Rittenauer, Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus OlssonArchive by Screenocean/Reuter https://www.screenocean.com

A TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH

And from the comments:

We jump ahead briefly to 1923 as this week is the anniversary of the Hitlerputsch and the Georg Elser Bomb in 1939. We will return to part 4 of 1920 in shortly. Many thanks to Rune V. Hartvig for contributing to the writing of this episode.

READ BEFORE YOU COMMENT: This episode was recorded before we had our studio, therefore our the sound is not great. Also READ OUR RULES:

RULES OF CONDUCT

STAY CIVIL AND POLITE we will delete any comments with personal insults, or attacks.

AVOID PARTISAN POLITICS AS FAR AS YOU CAN we reserve the right to cut off vitriolic debates.

HATE SPEECH IN ANY DIRECTION will lead to a ban.

RACISM, XENOPHOBIA, OR SLAMMING OF MINORITIES will lead to an immediate ban.

PARTISAN REVISIONISM, ESPECIALLY HOLOCAUST AND HOLODOMOR DENIAL will lead to an immediate ban.Thanks for reading, and now…. let’s make history!

November 8, 2018

80 years on from Kristallnacht

Jerrold Sobel reminds us that 80 years ago today, the Nazis got their desired pretext to launch a domestic terror campaign against the Jews:

Destroyed shopfront of a Jewish business in Magdeburg, November 9, 1938.

Photo Bundesarchiv Bild 146-1979-046-19, via Wikimedia Commons.

Hitler came into power in 1933 with a plan to expand Germany’s rule and to completely annihilate world Jewry. During this time between his ascension and 1938, progressively strident anti-Semitic laws known as the Nuremberg Laws were enacted in which governmental policies regulated every aspect of Jewish life.

As conditions increasingly worsened for Jews, a Polish Jewish student, Herschel Grynszpan, whose family was being deported after a lifetime living in Germany, acted out against the Nazis and assassinated a German diplomat, Ernst vom Rath, on November 7, 1938. Hitler could not have been happier: it was the pretext he had been seeking to up the ante of anti-Semitism from “law-based” to mob violence.

By November 9, rioting was already in full swing in all quarters of the Reich, which by this time included Austria. Minister of propaganda Josef Goebbels encouraged Hitler to allow further punishment of the Jews through more “spontaneous demonstrations” of violence. According to Goebbels’s diary, Hitler responded: “[D]emonstrations should be allowed to continue. The police should not be withdrawn. For once the Jews should get the feel of popular anger.”

And did they ever. On the nights of November 9 and 10, 1938, unspeakable assaults upon Jewish women and men took place in Germany and Austria. When the majority of the mayhem finally ended on November 11, 30,000 Jewish men had been arrested and taken to concentration camps. Although figures vary, at least 100 fatalities were initially reported, the number growing into the hundreds due to subsequent mistreatment of those arrested.

Over 1,400 synagogues were burnt to the ground, and more than 7,500 businesses were likewise looted and torched. Jewish hospitals, homes, and schools fared no better. Those two nights of havoc would ignominiously become known as Kristallnacht: the night of the broken glass.

Soon, the world came to know the depredations wrought upon the Jewish people those nights. It was just the beginning, a precursor to the greatest ethnic mass murder of a people in the history of the world: the Holocaust.

October 16, 2018

Modernism and the “so-called international style … is the blight of Germany (and of almost everywhere else where it has been tried)”

Theodore Dalrymple on the awful concrete-and-glass monoliths of modern architecture, especially those designs by Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, and Gropius:

The modernism and so-called international style that is the blight of Germany (and of almost everywhere else where it has been tried, which is almost everywhere in the world), and which the author of the article appears to think is apolitical, was hardly without its intellectual, ideological, and political foundations.

And what hideous intellectual, ideological, and political foundations they were! The great figures of modernism — great, that is, in the scope and degree of their baleful influence, not great in artistic or aesthetic merit — were from the first totalitarian in spirit. They were toadies to the rich and bullies to the poor; they were communists and fascists (not in the merely metaphorical sense, either), and by a mixture of ardent self-promotion, bureaucratic scheming, and intellectual terrorism managed to gain virtual control of the world’s schools of architecture. Just try saying in a French architectural school what is perfectly obvious, that Le Corbusier was not a genius except in self-advertisement, that his fascist ideas were repugnant, that he regarded humans in his cities much as we all regard bedbugs in beds, that during the Occupation he suggested deporting millions of people from Paris because he thought they had no business to be there, that his designs were incompetent, and that his constructions were instinct with and the very embodiment of his odious ideas, and see how far you get up the academic ladder! (How, incidentally, were the world’s most beautiful cities and buildings erected without the aid of architectural schools?) Anyone interested in the ideological foundations, as well as effects, of architectural modernism should read James Stevens Curl’s recently published Making Dystopia: The Strange Rise and Survival of Architectural Barbarism (Oxford), a magisterial and to me unanswerable account of one of the greatest aesthetic disasters to have befallen Europe in all its history. A single modernist building in a townscape is like a dead mouse in a bowl of soup, that is to say you cannot very well ignore it however splendid its surroundings may otherwise be.

Ah, you might protest, we have moved on from Mies van der Rohe et al., and so we have. (By the way, Professor Curl is very amusing on the opportunistic evolution of Mies van der Rohe’s name, as well as his equally opportunistic passage from being pro-Nazi to purely careerist refugee from Nazism.) Nonetheless two things need to be said about this supposed moving on from modernism to postmodernism and other isms: first that the damage, reparable only by demolition on a vast and inconceivable scale, has been done, and second that change is not by itself necessarily for the better. The capacity of eminent architects to spend vast sums of money to build aesthetic monstrosities fit to make Vitruvius weep is illustrated by the Whitney Museum in New York and the Philharmonie in Paris, the latter in particular of truly astonishing hideousness, that would have been almost comical had it not absorbed and wasted so much money, in the process becoming for many generations of the future as pleasing an aesthetic experience as a foreign body in the eye.

The mystery is how and why the patrons, those who choose the designs, stand for it. The key, I suppose, is to be found in Hans Christian Andersen — the Emperor’s New Clothes. The patrons are afraid to be thought by the architects not to understand: an accusation that Le Corbusier leveled decades ago at all those who did not approve of his plans to destroy old cities and cover the world with an ocean of raw concrete and a forest of almost identical towers. In other words, it is intellectual and moral cowardice that makes the world go round.

October 7, 2018

QotD: Hitler’s over-arching “grand strategy”

… on the internal evidence of Mein Kampf, it is difficult to believe that any real change has taken place in Hitler’s aims and opinions. When one compares his utterances of a year or so ago with those made fifteen years earlier, a thing that strikes one is the rigidity of his mind, the way in which his world-view doesn’t develop. It is the fixed vision of a monomaniac and not likely to be much affected by the temporary manoeuvres of power politics. Probably, in Hitler’s own mind, the Russo-German Pact represents no more than an alteration of time-table. The plan laid down in Mein Kampf was to smash Russia first, with the implied intention of smashing England afterwards. Now, as it has turned out, England has got to be dealt with first, because Russia was the more easily bribed of the two. But Russia’s turn will come when England is out of the picture — that, no doubt, is how Hitler sees it. Whether it will turn out that way is of course a different question.

Suppose that Hitler’s programme could be put into effect. What he envisages, a hundred years hence, is a continuous state of 250 million Germans with plenty of “living room” (i.e. stretching to Afghanistan or thereabouts), a horrible brainless empire in which, essentially, nothing ever happens except the training of young men for war and the endless breeding of fresh cannon-fodder. How was it that he was able to put this monstrous vision across? It is easy to say that at one stage of his career he was financed by the heavy industrialists, who saw in him the man who would smash the Socialists and Communists. They would not have backed him, however, if he had not talked a great movement into existence already. Again, the situation in Germany, with its seven million unemployed, was obviously favourable for demagogues. But Hitler could not have succeeded against his many rivals if it had not been for the attraction of his own personality, which one can feel even in the clumsy writing of Mein Kampf, and which is no doubt overwhelming when one hears his speeches …. The fact is that there is something deeply appealing about him. One feels it again when one sees his photographs — and I recommend especially the photograph at the beginning of Hurst and Blackett’s edition, which shows Hitler in his early Brownshirt days. It is a pathetic, dog-like face, the face of a man suffering under intolerable wrongs. In a rather more manly way it reproduces the expression of innumerable pictures of Christ crucified, and there is little doubt that that is how Hitler sees himself. The initial, personal cause of his grievance against the universe can only be guessed at; but at any rate the grievance is here. He is the martyr, the victim, Prometheus chained to the rock, the self-sacrificing hero who fights single-handed against impossible odds. If he were killing a mouse he would know how to make it seem like a dragon. One feels, as with Napoleon, that he is fighting against destiny, that he can’t win, and yet that he somehow deserves to. The attraction of such a pose is of course enormous; half the films that one sees turn upon some such theme.

George Orwell, “Review of Mein Kampf” by Adolf Hitler”, 1940.

September 17, 2018

“Nazis on Drugs” – Wehrmacht & Meth – Wunderwaffe?

Military History not Visualized

Published on 17 Aug 2018There some over-blown claims out there that the “Blitzkriege” were mainly achieved due to the use of Meth (Pervitin) and that historians had ignored this issue. Is it true or false? In this video we take a look at Pervitin, the Wehrmacht, the early German victories aka “Blitzkriege” and various aspects. Was Pervitin a Wunderwaffe? Was the Wehrmacht on Meth? How long was it used? And some aspects.

September 16, 2018

QotD: Austria’s share of the Nazi legacy

This ambiguity, or (to put it less kindly) dishonesty, if it really exists, replicates in symbolic fashion the attitude of Austria to its historical record in the 1930s and 40s. Officially, Austria was a victim of Nazi aggression; in reality, it was an enthusiastic participant in Nazi crimes. But whatever crimes Austrians as individuals committed during the war, they committed them as Germans, not as Austrians. They were responding only to force majeure; the Austrian state was not implicated.

Suspicion of Austria runs deep, and with good reason. Everyone thinks (though it cannot be proved or disproved) that Kurt Waldheim, the former Secretary-General of the United Nations, was elected president of the country not in spite of his Nazi past, but because of it. The Austrians claim that they insisted on voting for him because they resented the hypocritical reaction of the outside world to his candidature – surely, they said, powers with the combined intelligence resources of the United States, the Soviet Union, Britain and France must have known of his Nazi past when they accepted him as Secretary-General, so why should the Austrians themselves not accept him as President? Once again the Austrians were able to conceive of themselves as the injured party in the whole business.

Even the Austrian prohibition of Holocaust denial, under which the British Nazi-supporting historian David Irving was (in my view wrongfully) imprisoned until he recanted, or at least pretended to recant, is ambiguous. On the one hand, of course, it is a recognition of the moral monstrosity of what the Nazis did, and of the Austrians’ special responsibility for it; but on the other, it implies a deep mistrust of the Austrian people, who (it must have been feared by those who framed the law) might recant their anti-Nazism if they could.

Of course, there have been Austrians who were deeply disgusted by their countrymen. The greatest Austrian writer of the post-war period, Thomas Bernhard, inserted a famous clause in his will that repays reflection. He ordered that, for the duration of his legal copyright after his death, nothing he had ever written, including his plays, should ever be published or performed:

within the borders of the Austrian state, however that state

describes itself. I categorically emphasize that I want to have

nothing to do with the Austrian state and I safeguard myself

concerning my person and my work not only against every

interference but also against every approach by this Austrian

state to my person and my work for all time to come.‘For all time to come:’ that is a pretty strong injunction, implying as it does that the Austrian soul, or whatever you want to call it, is so tainted by its original sin, or sins, that it is irrecoverably and irremediably evil.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Austria and Evil”, New English Review, 2008-05.

September 5, 2018

QotD: Why did appeasing the Fascist dictators seem such a sensible policy?

It is a familiar student essay question, whether the revolution could have been averted, but for the world war and resultant loss of up to three million Russian lives. It seems more useful merely to suggest that, in the political and ideological climate of the early 20th century, the collectivist experiment was bound to be attempted somewhere, and Russia or China were obvious testbeds. The consequences for millions of Russian peasants, together with the ferocity of Soviet oppression, were successfully concealed from most western eyes for half a century. The 1789 French revolution killed only a few thousand aristocrats and transferred land to peasants, who thus became ardent upholders of property rights. The Russian version required liquidation of the entire governing class and transfer of land to collective ownership, an incomparably more radical proceeding. Douglas Smith’s 2012 book Former People gives a harrowing account of the fate of the Tsarist aristocracy.

In the West, the gullibility of the Webbs, Bernard Shaw and the rest of the ‘true believers’ was fed by a desperation to suppose the Soviet example viable. ‘Looking around us at our own hells,’ wrote the historian Philip Toynbee, who became a communist at Cambridge, ‘we had to invent an earthly paradise somewhere else’. As late as 1945, the leftist publisher Victor Gollancz brought posterity’s contempt upon himself by declining to publish Animal Farm, George Orwell’s great satire on Bolshevism.

For a counter-revolutionary contemporary perspective, it is impossible to understand the 1930s appeasement of the dictators without grasping the traumatic impact of events in Russia on the propertied classes everywhere. The Winter Palace was stormed only 16 years before Hitler came to power. For at least two decades, Europe’s ‘haves’ were far more frightened of Bolshevism than of fascism.

The ‘clubland hero’ novels of John Buchan and Sapper offer embarrassing glimpses of the British bourgeois view of Lenin’s people and their followers in the decades following the revolution. A belief took hold in polite circles that the bloodiest revolutionaries were not merely communists but also Jews, which meant they were doubly damned in St James’s clubs.

Max Hastings, “The centenary of the Russian revolution should be mourned, not celebrated”, The Spectator, 2016-12-10.