There have been bad years in human history. There have been worse days in human history. But according to a recent study summarized in Science magazine, the worst year in recorded history was 536AD:

Ask medieval historian Michael McCormick what year was the worst to be alive, and he’s got an answer: “536.” Not 1349, when the Black Death wiped out half of Europe. Not 1918, when the flu killed 50 million to 100 million people, mostly young adults. But 536. In Europe, “It was the beginning of one of the worst periods to be alive, if not the worst year,” says McCormick, a historian and archaeologist who chairs the Harvard University Initiative for the Science of the Human Past.

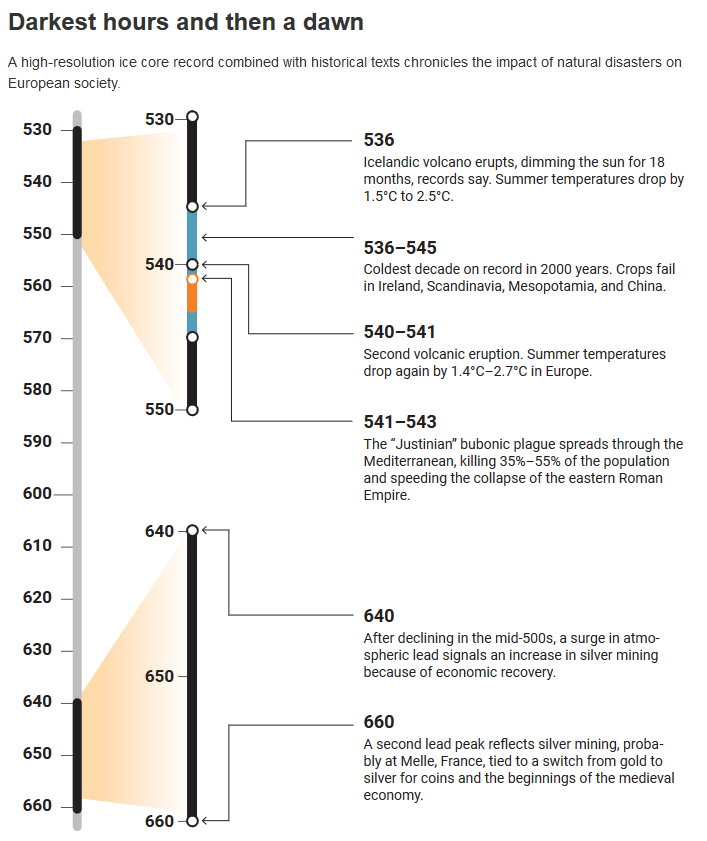

A mysterious fog plunged Europe, the Middle East, and parts of Asia into darkness, day and night — for 18 months. “For the sun gave forth its light without brightness, like the moon, during the whole year,” wrote Byzantine historian Procopius. Temperatures in the summer of 536 fell 1.5°C to 2.5°C, initiating the coldest decade in the past 2300 years. Snow fell that summer in China; crops failed; people starved. The Irish chronicles record “a failure of bread from the years 536–539.” Then, in 541, bubonic plague struck the Roman port of Pelusium, in Egypt. What came to be called the Plague of Justinian spread rapidly, wiping out one-third to one-half of the population of the eastern Roman Empire and hastening its collapse, McCormick says.

Historians have long known that the middle of the sixth century was a dark hour in what used to be called the Dark Ages, but the source of the mysterious clouds has long been a puzzle. Now, an ultraprecise analysis of ice from a Swiss glacier by a team led by McCormick and glaciologist Paul Mayewski at the Climate Change Institute of The University of Maine (UM) in Orono has fingered a culprit. At a workshop at Harvard this week, the team reported that a cataclysmic volcanic eruption in Iceland spewed ash across the Northern Hemisphere early in 536. Two other massive eruptions followed, in 540 and 547. The repeated blows, followed by plague, plunged Europe into economic stagnation that lasted until 640, when another signal in the ice — a spike in airborne lead — marks a resurgence of silver mining, as the team reports in Antiquity this week.

H/T to Blazing Cat Fur for the link.