Tom Scott

Published 29 May 2017Inside the beautiful Alnwick Garden, behind a locked gate, there’s the Poison Garden: it contains only poisonous plants. Trevor Jones, head gardener, was kind enough to give a guided tour!

For more information about visiting the Castle, Garden, and poison garden: https://alnwickgarden.com/

(And yes, it’s pronounced “Annick”.)

(more…)

April 3, 2023

The poison garden of Alnwick

March 13, 2023

QotD: The components of an oath in pre-modern cultures

Which brings us to the question how does an oath work? In most of modern life, we have drained much of the meaning out of the few oaths that we still take, in part because we tend to be very secular and so don’t regularly consider the religious aspects of the oaths – even for people who are themselves religious. Consider it this way: when someone lies in court on a TV show, we think, “ooh, he’s going to get in trouble with the law for perjury”. We do not generally think, “Ah yes, this man’s soul will burn in hell for all eternity, for he has (literally!) damned himself.” But that is the theological implication of a broken oath!

So when thinking about oaths, we want to think about them the way people in the past did: as things that work – that is they do something. In particular, we should understand these oaths as effective – by which I mean that the oath itself actually does something more than just the words alone. They trigger some actual, functional supernatural mechanisms. In essence, we want to treat these oaths as real in order to understand them.

So what is an oath? To borrow Richard Janko’s (The Iliad: A Commentary (1992), in turn quoted by Sommerstein [in Horkos: The Oath in Greek Society (2007)]) formulation, “to take an oath is in effect to invoke powers greater than oneself to uphold the truth of a declaration, by putting a curse upon oneself if it is false”. Following Sommerstein, an oath has three key components:

First: A declaration, which may be either something about the present or past or a promise for the future.

Second: The specific powers greater than oneself who are invoked as witnesses and who will enforce the penalty if the oath is false. In Christian oaths, this is typically God, although it can also include saints. For the Greeks, Zeus Horkios (Zeus the Oath-Keeper) is the most common witness for oaths. This is almost never omitted, even when it is obvious.

Third: A curse, by the swearers, called down on themselves, should they be false. This third part is often omitted or left implied, where the cultural context makes it clear what the curse ought to be. Particularly, in Christian contexts, the curse is theologically obvious (damnation, delivered at judgment) and so is often omitted.

While some of these components (especially the last) may be implied in the form of an oath, all three are necessary for the oath to be effective – that is, for the oath to work.

A fantastic example of the basic formula comes from Anglo-Saxon Chronicles (656 – that’s a section, not a date), where the promise in question is the construction of a new monastery, which runs thusly (Anne Savage’s translation):

These are the witnesses that were there, who signed on Christ’s cross with their fingers and agreed with their tongues … “I, king Wulfhere, with these king’s eorls, war-leaders and thanes, witness of my gift, before archbishop Deusdedit, confirm with Christ’s cross” … they laid God’s curse, and the curse of all the saints and all God’s people on anyone who undid anything of what was done, so be it, say we all. Amen.” [Emphasis mine]

So we have the promise (building a monastery and respecting the donation of land to it), the specific power invoked as witness, both by name and through the connection to a specific object (the cross – I’ve omitted the oaths of all of Wulfhere’s subordinates, but each and every one of them assented “with Christ’s cross”, which they are touching) and then the curse to be laid on anyone who should break the oath.

Of the Medieval oaths I’ve seen, this one is somewhat odd in that the penalty is spelled out. That’s much more common in ancient oaths where the range of possible penalties and curses was much wider. The Dikask‘s oath (the oath sworn by Athenian jurors), as reconstructed by Max Frankel, also provides an example of the whole formula from the ancient world:

I will vote according to the laws and the votes of the Demos of the Athenians and the Council of the Five Hundred … I swear these things by Zeus, Apollo and Demeter, and may I have many good things if I swear well, but destruction for me and my family if I forswear.

Again, each of the three working components are clear: the promise being made (to judge fairly – I have shortened this part, it goes on a bit), the enforcing entity (Zeus, Apollo and Demeter) and the penalty for forswearing (in this case, a curse of destruction). The penalty here is appropriately ruinous, given that the jurors have themselves the power to ruin others (they might be judging cases with very serious crimes, after all).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Oaths! How do they Work?”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-06-28.

March 8, 2023

Feeding a Medieval Outlaw

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 7 Mar 2023

(more…)

February 18, 2023

George Hudson: Railway King or Prince of Darkness?

Jago Hazzard

Published 20 Dec 2020Entrepreneur, politician, businessman, visionary, benefactor, conman. There’s a lot to unpick with old George.

(more…)

February 6, 2023

Why Traditional English Cheddar Is Aged In Caves | Regional Eats

Food Insider

Published 9 Oct 2019The earliest record of cheddar anywhere is at Cheddar, in Somerset, in 1170. The land around this village has been at the heart of English cheesemaking since the 15th century. Today, as many Cheddar producers have upscaled and require more land, there is only one traditional cheesemaker left in the village.

(more…)

January 22, 2023

QotD: Evolution of the nation-state

The Hundred Years’ War laid the foundations for the modern state. Exaggerating only a little for effect, when “England” and “France” went to war over some convoluted feudal nonsense in 1337, nobody not directly in the armies’ path cared. By 1453, though, both sides had to clearly articulate just why they were fighting in order to keep the war going. “National chauvinism” turned out to be a pretty good answer for the French — who, after all, were on the receiving end of most of the physical damage — but it worked ok for England, too. Early Modern English history makes a lot more sense when you know about the Pale of Calais.

It took the rest of Europe another 150 years, but the Thirty Years’ War did the trick. What started as another of the endless doctrinal conflicts kicked off by the Reformation ended with the creation of the modern nation-state. Cardinal Richelieu really was a Cardinal — a prince of the Roman Catholic Church, a guy with a legitimate chance of being elected Pope. This man brought Catholic France into the war on the Protestant side for “reasons of state”. This made sense in 1631 … and the war still had another 17 years to run.

Speaking of, the treaty that ended the Thirty Years’ War, the famous Peace of Westphalia, is credited with creating the modern nation-state. Which it did, but since we decided back in 1946 that nationalism was the worst possible sin, we Postmoderns forgot what everyone around the treaty table knew: That “nation” and “state” are inseparable. The nation-state, which for clarity’s sake will henceforth be known as the ethno-state, is the biggest stable form of human organization.

Severian, “The Libertarian Moment?”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-03-19.

January 21, 2023

When did England become that sneered-at “nation of shopkeepers”?

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes considers when the English stopped being a “normal” European nation and embraced industry and commerce instead of aristocratic privilege:

England in the late eighteenth century was often complimented or disparaged as a “nation of shopkeepers” — a sign of its thriving industry and commerce, and the influence of those interests on its politics.

But when did England start seeing itself as a primarily commercial nation? When did the interests of its merchants and manufacturers begin to hold sway against the interests of its landed aristocracy? The early nineteenth century certainly saw major battles between these competing camps. When European trade resumed in 1815 after the Napoleonic Wars, an influx of cheap grain threatened the interests of the farmers and the landowners to whom they paid rent. Britain’s parliament responded by severely restricting grain imports, propping up the price of grain in order to keep rents high. These restrictions came to be known as the Corn Laws (grain was then generally referred to as “corn”, nothing to do with maize). The Corn Laws were to become one of the most important dividing lines in British politics for decades, as the opposing interests of the cities — workers and their employers alike, united under the banner of Free Trade — first won greater political representation in the 1830s and then repeal of the Corn Laws in the 1840s.

The Corn Laws are infamous, but I’ve increasingly come to see their introduction as merely the landed gentry’s last gasp — them taking advantage of a brief window, after over two centuries of the declining economic importance of English agriculture, when their political influence was disproportionately large. In fact, I’ve noticed quite a few signs of the rising influence of urban, commercial interests as early as the early seventeenth century. And strangely enough, this week I noticed that in 1621 the English parliament debated a bill that was almost identical to the 1815 Corn Laws — a bill designed to ban the importation of foreign grain below certain prices.

But in this case, it failed. In the 1620s it seems that the interests of the cities — of commerce and manufacturing — had already become powerful enough to stop it.

The bill appeared in the context of a major economic crisis that, for want of a better term, ought to be called the Silver Crisis of 1619-23. Because of the outbreak of the Thirty Years War, the various mints of the states, cities, and princelings of Germany began to outbid one another for silver, debasing their silver currencies in the process. The knock-on effect was to draw the silver coinage — the lifeblood of all trade — out of England, and at a time when the country was already unusually vulnerable to a silver outflow. (For fuller details of the Silver Crisis and why England was so vulnerable to it, I’ve written up how it all worked here.)

The sudden lack of silver currency was a major problem, and all the more confusing because it coincided with a spate of especially bountiful harvests. As one politician put it, “the farmer is not able to pay his rent, not for want of cattle or corn but money”. A good harvest might seem a time for farmers and their landlords to rejoice, but it could also lead to a dramatic drop in the price of grain. Good harvests tended to cause deflation (which the Silver Crisis may have made much worse than usual by disrupting the foreign market for English grain exports). An influential court gossip noted in a letter of November of 1620 that “corn and cattle were never at so low a rate since I can remember … and yet can they get no riddance at that price”. Just a few months later, in February 1621, the already unbelievable prices he quoted had dropped even further.

Despite food being unusually cheap, however, the cities and towns that ought to have benefitted were also struggling. The Silver Crisis, along with the general disruption of trade thanks to the Thirty Years War, had reduced the demand for English cloth exports. And this, in turn, threatened to worsen the general shortage of silver coin — having a trade surplus, from the value of exports exceeding imports, was one of the only known ways to boost the amount of silver coming into the country. England had no major silver mines of its own.

It’s in this context that some MPs proposed a ban on any grain imports below a certain price. They argued that not only were low prices and low rents harming their farming and landowning constituents, but that importing foreign grain was undermining the country’s balance of trade. They argued that it was one of the many causes of silver being drawn abroad and worsening the crisis.

January 12, 2023

Early royal “spares” in English history

Ed West considers the time-honoured Ottoman habit of strangling the new Sultan’s half-brothers on his accession to the throne and notes that after the practice was discontinued, many notables in the empire thought it also marked a down-turn in the quality of later Sultans. The British crown never had such a formal tradition, although brotherly love seems to have been in very short supply a thousand years ago:

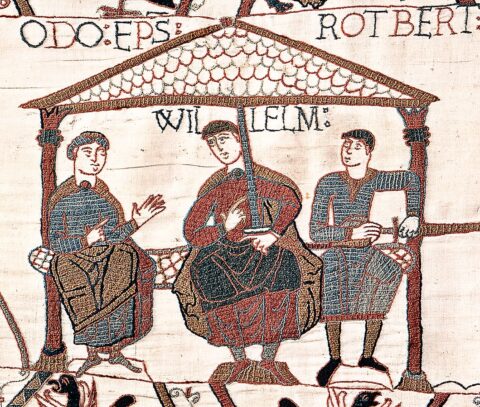

Panel from the Bayeux Tapestry – this one depicts Bishop Odo of Bayeux, Duke William, and Count Robert of Mortain.

Scan from Lucien Musset’s The Bayeux Tapestry via Wikimedia Commons.

Tales of royal brothers at war are a common theme, a staple of Norse sagas in particular, a recent example being the television series Vikings, and the brothers Ragnar and Rollo. William and Harry’s own family story in England begins with a tale told in one 14th century Icelandic saga, Hemings þáttr, which draws on older Norwegian stories to recall two royal brothers who became deadly rivals, Harold and Tostig.

Harold, as Earl of Wessex and the second most powerful man in England, had had his brother installed as Earl of Northumbria, where he had made himself immensely unpopular and provoked an uprising. When in 1065 Harold did a deal with the northerners to remove his sibling — presumably in exchange for the Northumbrians supporting his claim to the throne when the ailing King Edward passed away — Tostig fled abroad, embittered and determined to get revenge. Later accounts suggest that Harold and Tostig were rivals from an early age, one story having the young brothers fighting at the royal court as youngsters. Who knows, maybe Harold got the bigger room.

Tostig, now an exile, travelled around the North Sea looking for someone to help him invade England, finally finding his man with the terrifying Norwegian giant Harald Hardraada. Tostig had told all the Norwegians he was popular back home, but when they arrived in York they found that their English ally was in fact widely despised, and that not a single person came out to greet the former earl.

Tostig was killed soon after, in battle with his brother, having first (supposedly) exchanged words in this legendary meeting.

Harold himself would follow soon, victim of the English aristocracy’s great forefather William the Conqueror, whose success is illustrated by the naming patterns that followed. Harold’s brothers were Sweyn, Tostig, Gyrth, Leofwine and Wulfnoth; the Conqueror’s sons Robert, Richard, William and Henry. We haven’t had any Prince Wulfnoths recently.

The Conqueror’s son Richard having died in a hunting accident, the surviving Norman brothers had similarly fallen out, by one account the feud starting with a practical joke where William and Henry had poured a bucket of urine over eldest brother Robert. But mainly it was over land and power: after their father’s death Robert was made Duke of Normandy, the middle brother became William II of England, while Henry had to make do with just a cash payment.

Yet when William died in a mysterious hunting accident in the New Forest in 1100, Henry was conveniently close enough to reach the Treasury at Winchester within an hour to claim the crown. Six years later he invaded Normandy, with a partly English army, and captured his surviving brother, keeping Robert imprisoned for the rest of his life.

Henry I ruled for 35 years, but his long reign was followed by a civil war between his daughter Matilda and nephew Stephen, resulting in the rise of a new dynasty, the House of Anjou, or Plantagenets — so defined by internal conflict that Francis Bacon called them “a race much dipped in their own blood”.

Matilda’s husband Geoffrey Plantagenet had his brother Elias imprisoned, and Geoffrey’s son, King Henry II, had also gone to war with his younger brother, also Geoffrey. Even Geoffrey Plantagenet’s grandfather Fulk “the Quarreller” had spent over 30 years fighting for control of the county with his older brother, yet another Geoffrey.

Henry II in contrast fought his four sons and, after his death, his heir Richard I would also face rebellion from his younger brother John. When the Lionheart returned from crusade to deal with his deeply unlovable sibling he was remarkably forgiving, telling him: “Think no more of it, brother: you are but a child who has had evil counsellors.” This was despite John being 27 at the time.

More than two centuries later the House of Plantagenet came crashing down with a war pitting cousin against cousin, although brothers also fell out in the form of Edward IV and George, Duke of Clarence.

Both men were tall, blond and handsome, and both had a cruel and violent streak, but here the younger brother was impulsive, vain and foolish. He lacked maturity or self-control, was easily flattered and tempted into unwise decisions. He had been given vast estates and a lavish household but resented his older brother, who had also blocked his marriage to the daughter of the country’s largest landowner.

So Clarence had joined in the overthrow of Edward in 1470, while the youngest brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester, had remained loyal. However, when Edward returned to England the following March and Clarence led 4,000 men out to fight him, he was talked into changing sides again.

Clarence was forgiven, but the two brothers looked upon each other “with no very fraternal eyes”, and five years later he seems to have lost his mind after his wife died during childbirth. He accused the king of “necromancy” and of poisoning his subjects, and when brought before his brother made things much worse by claiming that Edward was a bastard. He was put to death.

Apparently, a soothsayer had also told King Edward that “G” would take his crown, and this must have fuelled his paranoia about George; after all, his other brother, the loyal Richard of Gloucester, would never do such a thing.

Such fraternal feuding ended with the rise of the Tudors and the conflicts between the House of Stuart and Parliament. There would be no more point in younger brothers threatening the monarch because the monarch no longer really had power; the royal family had evolved into a business, “the firm”, one in which hierarchies were clear and immovable, and the fortunes of family members were clearly joined.

January 8, 2023

The (historical) lure of London

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes considers the puzzle that was the phenomenol growth of London, even at a time that England had a competitive advantage in agricultural exports to the continent:

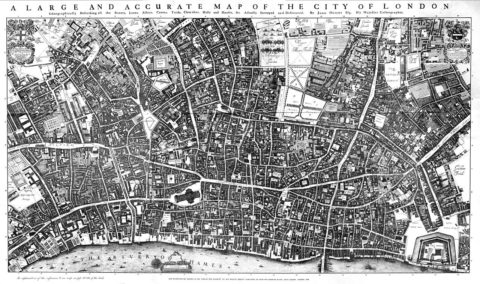

… the extraordinary inflow of migrants to London in the period when it grew eightfold — from an unremarkable city of a mere 50,000 souls in 1550, to one of the largest cities in Europe in 1650, boasting 400,000. I’ve written about that growth a few times before, especially here. It may not sound like much today, but it has to be one of the most important facts in British economic history. It is, in my view, the first sign of an “Industrial Revolution”, and certainly the first indication that there was something economically weird about England. It requires proper explanation.

In brief, the key question is whether the migrants to London — almost all of whom came from elsewhere in England — were pushed out of the countryside, thrown off their land thanks to things like enclosure, or pulled by London’s attractions.

I think the evidence is overwhelmingly that they were pulled and not pushed:

- The English rural population continued to grow in absolute terms, even if a larger proportion of the total population made their way to London. The population working in agriculture swelled from 2.1 million in 1550 to about 3.3 million in 1650. Hardly a sign of widespread displacement.

- As for the people outside of agriculture, many remained in or even fled to the countryside. In the 1560s, for example, York’s textile industry left for the countryside and smaller towns, pursuing lower costs of living and perhaps trying to escape the city’s guild restrictions. In 1550-1650, the population engaged in rural industry — largely spinning and weaving in their homes — swelled from about 0.7 to 1.5 million. Again, it doesn’t exactly suggest rural displacement. If anything, the opposite.

- There were in fact large economic pressures for England to stay rural. England for the entire period was a net exporter of grain, feeding the urban centres of the Netherlands and Italy. The usual pattern for already-agrarian economies, when faced with the demands of foreign cities, is to specialise further — to stay agrarian, if not agrarianise more. It’s what happened in much of the Baltic, which also fed the Dutch and Italian cities. Despite the same pressures for England to agrarianise, however, London still grew. To my mind, it suggests that London had developed an independent economic gravity of its own, helping to pull an ever larger proportion of the whole country’s population out of agriculture and into the industries needed to supply the city.

- As for the supposed push factor, enclosure, the timing just doesn’t fit. Enclosure had been happening in a piecemeal and often voluntary way since at least the fourteenth century. By 1550, before London’s growth had even begun, by one estimate almost half of the country’s total surface had already been enclosed, with a further quarter gradually enclosed over the course of the seventeenth century. A more recent estimate suggests that by 1600 already 73% of England’s land had been enclosed. As for the small remainder, this was mopped up by Parliament’s infamous enclosure acts from the 1760s onwards — much too late to explain London’s population explosion.

- Perhaps most importantly, people flocked specifically to London. In 1550 only about 3-4% of the population lived in cities. By 1650, it was 9%, a whopping 85% of whom lived in London alone. And this even understates the scale of the migration to the city, because so many Londoners were dropping dead. It was full of disease in even a good year, and in the bad it could lose tens of thousands — figures equivalent or even larger than the entire populations of the next largest cities. Waves upon waves of newcomers were needed just to keep the city’s population stable, let alone to grow it eightfold. In the seventeenth century the city absorbed an estimated half of the entire natural increase in England’s population from extra births. If England’s urbanisation had been thanks to rural displacement, you’d expect people to have flocked to the closest, and much safer, cities, rather than making the long trek to London alone.

It’s this last point that I’ve long wanted to flesh out some more. The further people were willing to trek to London, the more strongly it suggests that the city had a specific pull. I’d so far put together a few dribs and drabs of evidence for this. Whereas towns like Sheffield drew its apprentices from within a radius of about twenty miles, London attracted young people from hundreds of miles away, with especially many coming from the midlands and the north of England. Indeed, London’s radius seems to have shrunk over the course of the seventeenth century, suggested that they came from further afield during the initial stages of growth. Records of court witnesses also suggest that only a quarter of men in some of London’s eastern suburbs were born in the city or its surrounding counties.

December 12, 2022

QotD: Oversensitivity is not constrained by the mere passage of time

This newspaper lost its editor-in-chief and guiding light to academia a few weeks ago, and we — you know, the talent! — are all still moping. Meanwhile, however, the job is open, and is being publicly advertised. The pay is pretty good, but if you are thinking of applying, you should really be conscious of what a top editor has to deal with these days. BBC News provided a good example on Wednesday, offering a brief account of a controversy at the Teesdale Mercury, a rural paper in princely, scenic County Durham. (The county called Durham in England, that is.)

It seems a reader of the Mercury ran across a brief news item about the suicide of a 16-year-old girl in its pages, and was horrified at the sensational, detailed nature of the report. The story described Dorothy Balchin as being “of a reserved and morbid disposition” and described the romantic disappointment — a beau’s emigration to Australia — that preceded her suicide. The newspaper noted that a photograph of her boyfriend was found immediately below her hanged body, and even printed the text of two notes she left. In other words, the news copy broke every rule that newspapers now normally observe in mentioning suicide.

But of course no one had thought of any of those rules in the year 1912.

Which is when the story had appeared in the Mercury.

Which didn’t stop some reader from complaining to the paper in the year 2019.

Colby Cosh, “Want a newspaper job? Dream of making films? Be careful what you wish for”, National Post, 2019-05-09.

December 10, 2022

Ed West finds nice-ish things to say about the French

It’s actually part two, which I’m sure would astonish many a Brit:

The Royal Standard of the King of France (and by default, the national flag), used between 1638 and 1790.

Wikimedia Commons.

“When, after their victory at Salamis, the generals of the various Greek states voted the prizes for distinguished individual merit, each assigned the first place of excellence to himself, but they all concurred in giving their second votes to Themistocles,” wrote the great 19th-century historian Edward Creasy. “This was looked on as a decisive proof that Themistocles ought to be ranked first of all. If we were to endeavour, by a similar test, to ascertain which European nation has contributed the most to the progress of European civilization, we should find Italy, Germany, England, and Spain, each claiming the first degree, but each also naming France as clearly next in merit. It is impossible to deny her paramount importance in history.”

France is central to the story of Europe, and indeed of Britain. It is almost impossible to understand England’s history without appreciating the relationship with its closest continental neighbour. It is a love-hate affair originating in a grand inferiority complex, a long rivalry that continues tomorrow [Saturday] when England meet France in the World Cup quarter-finals.

In a piece last year I cited some of the most endearing/maddening things about the French, all of which contributed to a sense of amused frustration on our part:

Only in France would football fans protest that a local restaurant had lost a Michelin Star, as happened in Lyon two years ago. Only in France would an expedition to the Himalayas — of huge national importance — fail because it was weighed down by eight tonnes of supplies, including 36 bottles of champagne and “countless” tins of foie gras. And only in France would you get actual wine terrorists, the Comité Régional d’Action Viticole, who have bombed shops, wineries and other things responsible for importing foreign produce. This is a country which only reluctantly in the 1950s stopped giving school children a nutritious drink for their health, by which the French meant not milk but cider.

This is a country where mistresses are so much part of life that they can legally inherit, and where murder doesn’t really count if it’s done for love. One of France’s most famous socialites, Henriette Caillaux, shot dead the editor of Le Figaro just before the First World War and received just four months in jail because it was a crime passionnel. So that’s all right then.

But there are so many other things to love about our strange neighbours …

The Anglo-French relationship is a difficult one, reflected in the troubled history of royal marriages. Charles I’s Catholic wife Henrietta Maria was a drag on his popularity among excitable Protestant radicals, and turned out to be the last French consort; in the 14th century Edward II’s wife Isabella overthrew him and, perhaps, conspired to have him killed, after a rocky marriage that began badly when he brought his lover to the coronation and acted inappropriately affectionate towards him. But then, as Edith Cresson pointed out, this is to be expected when you marry an Englishman.

In 1514 Louis XII married an English bride, Henry VIII’s sister Mary; she was 18, he was 53, and had syphilis, so she must have been delighted about the whole thing; however, within weeks she had “danced him to death”, the sex apparently proving too exciting for his nervous system. Francesco Vettori, Florence’s ambassador to Rome, wrote that King Louis had a lady “so young, so beautiful and so swift that she had ridden him right out of the world”.

***

Perhaps not a terrible way for a Frenchman to go, and not the last French head of state to die in a similar manner. President Félix Faure expired in 1899 while with his mistress, after which his funeral featured this very understated carriage.

***

Numerous French presidents have had affairs, although Francois Mitterrand actually had a secret second family while in the Élysée Palace. Mitterrand’s last meal was also ultra-French: “He’d eaten oysters and foie gras and capon — all in copious quantities — the succulent, tender, sweet tastes flooding his parched mouth. And then there was the meal’s ultimate course: a small, yellow-throated songbird that was illegal to eat. Rare and seductive, the bird — ortolan — supposedly represented the French soul. And this old man, this ravenous president, had taken it whole — wings, feet, liver, heart. Swallowed it, bones and all. Consumed it beneath a white cloth so that God Himself couldn’t witness the barbaric act.”

***

The French are world outliers in their attitudes to adultery, the only country where a majority of people think it’s fine. Germany is number two in this index of permissiveness while the Americans, of course, are the most disapproving western nation.

December 1, 2022

Medieval Table Manners

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 19 Jul 2022

(more…)

November 30, 2022

QotD: The rise of liberalism

Liberalism, in its own turn, came out of the accidents of European reformations, revolts, and revolutions, in an existing polity of hundreds of more or less independent political units, such as the Dutch cities in their Golden Age, or the Kleinstaaterei of German polities even after 1648. The success of the accidents made people bold — not necessarily and logically, but contingently and factually. For example, the Dutch Revolt 1568–1648 imparted the idea of civic autonomy against the hegemon of the time, Spain, and by analogy against other hegemons international and local. For another example, the initial successes of the English Civil War of the 1640s made ordinary people think they could make the world anew. For still another example, the Radical Reformation of Anabaptists, Mennonites, Congregationalists, and later the Quakers and Methodists let people take charge of their own religious lives, and by analogy their economic lives. The tiny group of English Quakers made for Lloyd’s insurance, Barclay’s bank, Cadbury’s chocolate. It was in the religious case not the doctrines of Calvinism as such (not the Protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism) but a flattened church governance that mattered for inspiriting people.

In sum, as one of the Levellers in the English Civil War of the 1640s, Richard Rumbold, said from the scaffold in 1685, “there was no man born marked of God above another, for none comes into the world with a saddle on his back, neither any booted and spurred to ride him.” It was a shocking thought in a hierarchical society. In 1685 the crowd gathered to see Rumbold hanged surely laughed at such a sentiment. By 1885 it was a solemn cliché.

Dierdre McCloskey, “How Growth Happens: Liberalism, Innovism, and the Great Enrichment (Preliminary version)” [PDF], 2018-11-29.

November 14, 2022

QotD: The first modern revolution

The first modern revolution was neither French nor American, but English. Long before Louis XVI went to the guillotine, or Washington crossed the Delaware, the country which later became renowned for stiff upper lips and proper tea went to war with itself, killed its king, replaced its monarchy with a republican government and unleashed a religious revolution which sought to scorch away the old world in God’s purifying fire.

One of the dark little secrets of my past is my teenage membership of the English Civil War Society. I spent weekends dressed in 17th-century costumes and oversized helmets, lined up in fields or on medieval streets, re-enacting battles from the 1640s. I still have my old breeches in the loft, and the pewter tankard I would drink beer from afterwards with a load of large, bearded men who, just for a day or two, had allowed themselves to be transported back in time.

I was a pikeman in John Bright’s Regiment of Foote, a genuine regiment in the parliamentary army. We were a Leveller regiment, which is to say that this part of the army was politically radical. For the Levellers, the end of the monarchy was to be just the beginning. They aimed to “sett all things straight, and rayse a parity and community in the kingdom”. Among their varied demands were universal suffrage, religious freedom and something approaching modern parliamentary democracy.

The Levellers were far from alone in their ambitions to remake the former Kingdom. Ranters, Seekers, Diggers, Fifth Monarchists, Quakers, Muggletonians: suddenly the country was blooming with radical sects offering idealistic visions of utopian Christian brotherhood. In his classic study of the English Revolution, The World Turned Upside Down, historian Christopher Hill quotes Lawrence Clarkson, leader of the Ranters, who offered a radical interpretation of the Christian Gospel. There was no afterlife, said Clarkson; only the present mattered, and in the present all people should be equal, as they were in the eyes of God:

“Swearing i’th light, gloriously”, and “wanton kisses”, may help to liberate us from the repressive ethic which our masters are trying to impose on us — a regime in which property is more important than life, marriage than love, faith in a wicked God than the charity which the Christ in us teaches.

Modernise Clarkson’s language and he could have been speaking in the Sixties rather than the 1640s. Needless to say, his vision of free love and free religion, like the Leveller vision of universal equality, was neither shared nor enacted by those at the apex of the social pyramid. But though Cromwell’s Protectorate, and later the restored monarchy, attempted to maintain the social order, forces had been unleashed which would change England and the wider world entirely. Some celebrated this fact, others feared it, but in their hearts everyone could sense the truth that Gerard Winstanley, leader of the Diggers, was prepared to openly declare: “The old world … is running up like parchment in the fire”.

Paul Kingsnorth, “The West needs to grow up”, UnHerd, 2022-07-29.

November 5, 2022

Repost: Remember, Remember the Fifth of November

Today is the anniversary of the Gunpowder Plot:

Everyone knows what the Gunpowder Plotters looked like. Thanks to one of the best-known etchings of the seventeenth century we see them “plotting”, broad brims of their hats over their noses, cloaks on their shoulders, mustachios and beards bristling — the archetypical band of desperados. Almost as well known are the broad outlines of the discovery of the “plot”: the mysterious warning sent to Lord Monteagle on October 26th, 1605, the investigation of the cellars under the Palace of Westminster on November 4th, the discovery of the gunpowder and Guy Fawkes, the flight of the other conspirators, the shoot-out at Holbeach in Staffordshire on November 8th in which four (Robert Catesby, Thomas Percy and the brothers Christopher and John Wright) were killed, and then the trial and execution of Fawkes and seven others in January 1606.

However, there was a more obscure sequel. Also implicated were the 9th Earl of Northumberland, three other peers (Viscount Montague and Lords Stourton and Mordaunt) and three members of the Society of Jesus. Two of the Jesuits, Fr Oswald Tesimond and Fr John Gerard, were able to escape abroad, but the third, the superior of the order in England, Fr Henry Garnet, was arrested just before the main trial. Garnet was tried separately on March 28th, 1606 and executed in May. The peers were tried in the court of Star Chamber: three were merely fined, but Northumberland was imprisoned in the Tower at pleasure and not released until 1621.

[. . .]

Thanks to the fact that nothing actually happened, it is not surprising that the plot has been the subject of running dispute since November 5th, 1605. James I’s privy council appears to have been genuinely unable to make any sense of it. The Attorney-General, Sir Edward Coke, observed at the trial that succeeding generations would wonder whether it was fact or fiction. There were claims from the start that the plot was a put-up job — if not a complete fabrication, then at least exaggerated for his own devious ends by Robert Cecil, Earl of Salisbury, James’s secretary of state. The government’s presentation of the case against the plotters had its awkward aspects, caused in part by the desire to shield Monteagle, now a national hero, from the exposure of his earlier association with them. The two official accounts published in 1606 were patently spins. One, The Discourse of the Manner, was intended to give James a more commanding role in the uncovering of the plot than he deserved. The other, A True and Perfect Relation, was intended to lay the blame on Garnet.

But Catesby had form. He and several of the plotters as well as Lord Monteagle had been implicated in the Earl of Essex’s rebellion in 1601. Subsequently he and the others (including Monteagle) had approached Philip III of Spain to support a rebellion to prevent James I’s accession. This raises the central question of what the plot was about. Was it the product of Catholic discontent with James I or was it the last episode in what the late Hugh Trevor-Roper and Professor John Bossy have termed “Elizabethan extremism”?