Now, obviously, there are reasons why building infrastructure is expensive. One is that politicians have taken unto themselves the power to decide what infrastructure should be built how and where. Therefore infrastructure is built by fuckwits, obvious, innit? We’ve also allowed far too many people to dip their ladle in the gravy — that £300 million planning inquiry into a tunnel under the Thames. And did I say fuckwits already — that £100 million bat tunnel.

But one reason all these things are so expensive is because we’re not doing them on terra nullius. If we start with a bare field a ground source heat pump might well not be that bad an idea. Communal heating systems into an entirely new development, maybe.

But putting ground heat pumps into central London? Can’t do that ‘ere mate, someone’s already built central London right where you want to dig up. HS2 goes right through some of the most expensive — and inhabited by the highly vocal — countryside in the nation. Edinburgh, minor though it is, still has that central London problem.

This also explains why Mercury Comms employed the ferrets. The tubes already existed and fibreoptic could be stuffed down them. They didn’t have to dig up central London, see?

Agreed, this isn’t one of the world’s truly great insights but it is something to keep in mind. The reason building the infrastructure for the next level of civilisation costs so much is because we already have a civilisation. The existence of which gets in the way of the building men …

Tim Worstall, “Why Is Infrastructure So Damn F’n Expensive?”, It’s all obvious or trivial except …, 2024-11-18.

February 21, 2025

QotD: Why does it cost so much to build modern infrastructure?

June 5, 2024

HMCS Charlottetown: A formidable submarine-hunting force in Nato’s fleet

Forces News

Published Mar 1, 2024Conceived in the middle of the Cold War era, the Canadian Royal Navy frigate HMCS Charlottetown has evolved over three decades of service, becoming one of the most capable and adaptable ships in Canada’s navy.

After setting sail for Nato’s Exercise Steadfast Defender in the North Sea, she made a stop in Edinburgh en route to participating in the alliance’s largest training mission since the Cold War.

(more…)

August 29, 2023

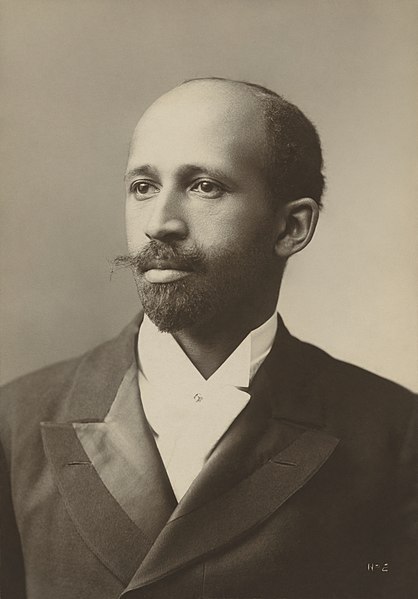

The Souls of Black Folk by W.E.B. Du Bois “runs so fantastically counter to the entire ideology of ‘decolonise'”

In Spiked, Brendan O’Neill finds himself surprised at the inclusion of a very unusual book on a list demanded by those pushing for “decolonization” of university curricula:

W.E.B. Du Bois by James E. Purdy, 1907, gelatin silver print, from the National Portrait Gallery which has explicitly released this digital image under the CC0 license.

Wikimedia Commons.

“Decolonise the curriculum” is a movement that wants university courses to focus less on dead white European males and more on writers of colour. Its argument is that black students need texts that speak directly to them. They need books by authors who look like them. They need books about experiences and ideas they can more readily relate to than they can the stuff written about in “high white culture”. Black students must be able to recognise themselves in what they study, we’re told, or else they’ll feel cheated and demeaned.

I was surprised to find that one of the leading decolonise movements, at the University of Edinburgh, was arguing for WEB Du Bois’ 1903 book, The Souls of Black Folk, to be included on the English curriculum. The activists said it was unreasonable to expect black students to engage with so many white authors. They also need to engage with people like Du Bois, in whose work they might “recognise themselves”. I was surprised, not because I think The Souls of Black Folk shouldn’t be on more university courses – absolutely it should. No, it’s because The Souls of Black Folk runs so fantastically counter to the entire ideology of “decolonise”. It made me wonder if these activists have even read it. Du Bois’ book contains some of the finest arguments you will ever read against the idea that high culture is a white thing that others cannot connect with.

One of my favourite passages in the book, from the chapter on what kind of education black men are fit for, touches on this very question. Here Du Bois makes his critique of those in his own time who were arguing that blacks only require basic education and industrial training. He describes his own experience of higher learning, writing:

I sit with Shakespeare and he winces not. Across the colour line I move arm in arm with Balzac and Dumas … From out the caves of evening that swing between the strong-limbed earth and the tracery of the stars, I summon Aristotle and Aurelius and they come all graciously with no scorn or condescension.

That passage, Du Bois’ moving belief that Shakespeare does not wince at him, captures a central thread of his writing: universalism. Du Bois agitates against accommodating to segregation or low expectations, and argues for the rights of “black folk” to assimilate into the spoils of civilisation; to become, as he puts it, “co-workers in the kingdom of culture”. To those in the late 1800s and early 1900s who argued that black people needed a targeted form of culture, one specific to their needs and capacities, Du Bois said: “We daily hear that an education that encourages aspiration, that sets the loftiest of ideals and seeks as an end culture and character rather than breadwinning, is the privilege of white men, and the danger and delusion of black men.”

Du Bois insisted that it is only through assimilation into the “kingdom of culture” that self-knowledge and self-improvement can truly occur. As he wrote: “Wed with Truth, I dwell above the veil.” The veil he’s referring to is the veil of colour, the one that separated blacks from whites in post-slavery America. For Du Bois, that veil was best lifted via assimilation into the American republic’s political universe and its realm of culture.

Du Bois’ critique of the notion that high culture was for white men, and would prove mystifying to black men, has sadly been superseded by an “anti-racism” with an entirely different outlook. Now, the supposedly radical stance is to believe that high culture is disorientating for black people, and possibly even damaging to their self-esteem, and therefore they require something more targeted. In short, they need release from the kingdom of culture. That, in essence, is what the decolonise movement desires: the “liberation” of non-white peoples from the cultural gains of Western civilisation. Behold the crisis of universalist belief.

July 11, 2022

British Transport Films: Elizabethan Express (1954)

mikeknell

Published 6 May 2014This 1954 documentary is uploaded in a couple of places, but here it is without breaks and in the correct aspect ratio. One of the classic railway films.

April 22, 2022

Lucy Worsely on The Jacobites & the Scottish Enlightenment

Whitehall Moll History Clips

Published 22 Jul 2018A segment on the Jacobites and the Scottish Enlightenment that blossomed in the face of Hanoverian oppression.

November 20, 2021

Meet The Last Artisans Making Traditional Bagpipes By Hand In Scotland’s Capital | Still Standing

Business Insider

Published 2 Jul 2021Bagpipes have been a symbol of Scottish heritage for centuries, but traditional artisans have faced stiff competition with the rise of mass manufacturing. Kilberry Bagpipes is now the last workshop in the capital city of Edinburgh where they still make them by hand.

For more information, visit:

https://kilberrybagpipes.com/——————————————————

#Bagpipes #Scotland #BusinessInsider

Business Insider tells you all you need to know about business, finance, tech, retail, and more.

Visit us at: https://www.businessinsider.com

BI on Instagram: https://read.bi/2Q2D29T

BI on Twitter: https://read.bi/2xCnzGF

BI on Amazon Prime: http://read.bi/PrimeVideoMeet The Last Artisans Making Traditional Bagpipes By Hand In Scotland’s Capital | Still Standing

From the comments:

Kilberry Bagpipes

1 month ago

It was a pleasure having you guys in to film with us! Thank you for putting together such a fantastic video illustrating what we do and why we do it! If anyone has any further questions or is keen to learn to play then please feel free to email us where we will be happy to help!All the best,

Dave and Ruari

The Kilberry Team

May 24, 2021

“The revolution will be defeated when people stop being scared”

Sean Gabb discusses some outrageous elements of the ongoing cultural revolution against freedom of speech in Britain, the United States and many other western nations:

David Hume Tower at the University of Edinburgh (listed building number 50189).

Photo by Enric via Wikimedia Commons.

If I am a self-employed plumber or electrician, I can speak my mind and laugh at the complaints. If, like the great majority in this country, I am a salaried employee — whether in the state or private sectors is unimportant: the pressures to conformity are the same in both sectors — I must be careful what I say. I am scared of the sack. I am scared of sudden redundancy. I am scared of missing out on promotions. I am scared of generally unfair treatment because of my opinions. I therefore hide my opinions. The Peter Tatchells among us then look round complacently, telling themselves and each other that silence equals agreement, and that the few squeaks of opposition are from “disreputable extremists.”

This explains the present unbalanced debates over slavery and colonialism. Take these examples:

- First, in September 2020, the David Hume Tower at Edinburgh University was “denamed”. Someone had bothered to read the 1748 essay “Of National Characters”, and found in one of its footnotes an unfashionable statement about race. It was at once set aside that Hume was a philosopher of at least considerable note. More important was the “non-overt disrespect, offence, and racism that Black students have to go through at the University of Edinburgh”.

- Second, the Music Department at Oxford is presently worried that its curriculum “structurally centres white European music”, and that this causes “students of colour great distress”. It therefore wants to change its focus from the European classical tradition to things like “Artists Demanding Trump Stop Using Their Songs”. It also wants to discourage students from studying musical notation, as this is a “colonialist representational system”.

I could give a third illustration, and a fourth. I could fill a pamphlet with more. Some would be more alarming, though few less absurd. But these two can stand well enough for all the others. What makes these debates so irritating is that they are not debates. One side can put its case just as it pleases. The other is reduced to accepting all the main charges and begging for mitigation: “What Hume said was evil and unpardonable — but he was important for other things.” Or: “I feel your pain, but Mozart owned no slaves, and everyone knows that Beethoven was really black.” Because it has been so humbly begged, full mitigation will, in both cases, be granted. Hume will continue to be studied in the universities. Music students at Oxford will continue to use the standard notation and to analyse the usual classics. But preventing these things was never part of the agenda. The agenda was and is to transform what were honoured or unquestioned parts of our civilisation into things useful but more or less suspect, things subject to a toleration that may be varied or withdrawn at any time without notice.

It should be plain that we are, in both England and America, living through a revolution. This is not a normal revolution as these things are considered. Unlike in France or Russia, there has been no overthrow of an established order, no burst of state violence, no establishment after that of an overtly new order. There are no secret police. There are no labour camps. No one is beaten to death in a police cell. All the same, we are living through a revolution. It is a revolution that has involved the gradual capture of education, the media, the administration, the charities and the more permeable religious institutions, and the recent aligning of the larger or more glamorous business concerns. I see no point in discussing its ultimate objects. I am not sure if these are wholly agreed. But its provisional object is the destruction of our traditional identity, and of our liberty so far as this stands in the way of that provisional object.

These two elements of the provisional object are equally important. Our civilisation is being pulled apart because doing so strips away the mass of associations that, left in place, might hold up the more alarming parts of the transformation. Opposition is so feeble not only because that is all that will be tolerated: feeble opposition is all that can be tolerated. This is a revolution in which opponents are not murdered, but only scared into silence. They are scared into silence chiefly by fear of destroyed or blighted careers. The revolution will be defeated when people stop being scared. Then, there will be vicious and unrelenting public mockery, and commercial boycotts, and shareholder rebellions, and lost elections, and the general feeling of solidarity and impunity still sometimes found in a football stadium.

January 16, 2021

Howard Anglin reviews The Riotous Passions of Robbie Burns

The Line now apparently also does book reviews:

I don’t know what I was expecting before I picked up John Ivison’s new book, The Riotous Passions of Robbie Burns, but it was not this. In my head, I’d already started composing the end of my review. Something round and pat and full of holiday hygge like: “So light the fire, pour yourself a dram of Annandale whisky, and enjoy …” Because Ivison grew up in Dumfries, where Burns spent the last years of his life, I suppose I expected a more personal narrative, not a work of historical fiction. One expects fiction from political journalists in their day jobs, not in a labour of love composed off the clock.

What I really expected was more of Burns’ poetry — the source of his enduring fame, after all — and less of his person, which was the source of his contemporary infamy. Instead, Ivison gives us something more interesting and unusual: the poetry of Burns’ non-poetic speech. Ivison has taken snippets, and sometimes cribbed whole paragraphs from, Burns’s copious surviving correspondence and woven them into dialogue that carries the story of the poet’s stay in Edinburgh between 1786 and 1788. By putting Burns’ actual words into his mouth, even if sometimes out of context, Ivison gives the reader a direct and plausible impression of Burns the man. We hear verbatim both the coarse tavern wit and the elemental passion that spilled into his prolific verse — sometimes into unprintable doggerel (literally: his poems later collected as The Merry Muses of Caledonia were banned as obscene in the U.K. until 1965), sometimes into achingly beautiful verses like “Flow gently, sweet Afton” or “Ae Fond Kiss.”

Ivison’s book sets us in Edinburgh at a time when, as he writes, “it was said if you stood at the Mercat Cross with a pistol, you could hit 50 geniuses, 50 bankers, 50 lawyers and 50 rogues at any given hour” (no doubt allowing for some overlap between latter two categories). Our narrator and guide is the newly-arrived and impressionable young lawyer’s apprentice, John Bruce, a composite and Zelig-like stand in for many young men of the poet’s acquaintance. (The only record of Burns meeting a John Bruce that I can find was a Rev. John Bruce, Minister of the Highland town of Forfar, whom the poet found “pleasant, agreeable and engaging.”) Through Burns, Bruce and the reader are introduced to the ways of women, drink, the printing business, drink, aristocratic libertinism, and a little more drink.

The two main plots, such as they are, link Bruce and Burns to the notorious escapades of Deacon Brodie, whom Burns met in real life, and to the poet’s long, futile, but apparently sincere courtship of the unhappily-married Agnes (sometimes Nancy) Maclehose. The real life letters between Burns and Maclehose, written under the pseudonyms “Sylvander” and “Clarinda,” make for moving reading and, in this telling, for surprisingly convincing dialogue between Burns and Maclehose and between Burns and Bruce. The text is especially affecting when the poet is in the grip of what he called his “low spirits & blue devils” and his usually florid speech turns fatalistic, brooding, and palpably human.

But the plots are not the point of this charming book; they are frames on which to hang Burns’s words and excuses to showcase Edinburgh as it was coming of age as an intellectual and commercial capital, with all the growing pains that entailed. Filling the city with historical characters, Ivison shows us the city as Burns found it, its population bursting out of the overbuilt medieval closes and wynds that lined the Royal Mile running down the hill from the castle and spreading across the North Bridge to New Town and down to the sea port at Leith.

August 13, 2019

Titania McGrath reviews the very best show at the Edinburgh Fringe this year

It is, of course, her own show:

There are over 2,000 shows at this year’s Edinburgh Festival Fringe, but only one that is really worth seeing. Titania McGrath’s Mxnifesto is a tour de force of political oratory that is unlikely to be surpassed in my lifetime. I have seen every single performance, except for the nights I’ve had off (usually when my self-diagnosed PTSD has flared up), and its cultural significance is indisputable. I’d go so far as to suggest that the Edinburgh Fringe should cease after this current year, given that its purpose has now surely been fulfilled.

I was warned against writing this piece. Apparently, it is frowned upon to write a review for your own show. I consider this yet another attempt to silence women’s voices by the forces of heteronormative patriarchy. Why should I, as a proud independent woman, not proclaim my own worth? I will not bend the knee to swaggering males who seek to oppress me with their “opinions”. I will not seek permission before declaring my own genius. Mxnifesto is a fucking masterpiece and I am only awarding it five stars because to give it six it might seem arrogant.

As one walks into the auditorium at the Pleasance Above, a charming little theater space that emphasizes McGrath’s humility, there is a collective tremble of anticipation among the crowd. After all, McGrath has a reputation not only for her wisdom, but also for her righteous anger. Like Joan of Arc, she has successfully fought for justice against incredible odds. But unlike Joan of Arc, she didn’t make the stupid mistake of getting herself burned to death in the process.

From the program description:

Titania McGrath is a radical intersectionalist poet committed to feminism, social justice and armed peaceful protest. As a millennial icon on the forefront of online activism, Titania is uniquely placed to explain to you why you are wrong about everything and how to become truly woke. “The latest genius twist in Britain’s long tradition of satirical spoof” (Daily Express). “Outrageous and hilarious” (Irish Independent). “Brilliant” (Daniel Sloss). “Titania McGrath is a genius” (Spectator). “Hilarious… perfectly captures the joyless tone of the woke Stasi” (Times). “Lampooning the language of social justice is a cheap shot” (Observer).

June 4, 2019

Missing Isle of Lewis chess piece discovered in Edinburgh

It’s always irritating when you lose a chess piece, but this one’s been missing for a long, long time:

A medieval chess piece that was missing for almost 200 years had been unknowingly kept in a drawer by an Edinburgh family.

They had no idea that the object was one of the long-lost Lewis Chessmen – which could now fetch £1m at auction.

The chessmen were found on the Isle of Lewis in 1831 but the whereabouts of five pieces have remained a mystery.

The Edinburgh family’s grandfather, an antiques dealer, had bought the chess piece for £5 in 1964.

He had no idea of the significance of the 8.8cm piece (3.5in), made from walrus ivory, which he passed down to his family.

They have looked after it for 55 years without realising its importance, before taking it to Sotheby’s auction house in London.

The Lewis Chessmen are among the biggest draws at the British Museum and the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh.

They are seen as an “important symbol of European civilisation” and have also seeped into popular culture, inspiring everything from children’s show Noggin The Nog to part of the plot in Harry Potter And The Philosopher’s Stone.

Sotheby’s expert Alexander Kader, who examined the piece for the family, said his “jaw dropped” when he realised what they had in their possession.

H/T to Colby Cosh for the link.

November 20, 2016

Know your audience, children’s division

M. Harold Page, guest-posting at Charles Stross’s blog:

Little Harry blinks at me through his heavy Sellotaped glasses. “What’s that for?”

“It’s a submachine gun,” I say. “It fires lots of bullets.” I mime. “Bang bang bang!”

I’m helping out on a school trip. Normally I avoid volunteering – it’s too easy for self employed parents to end up as the school’s go-to. However this visit is to Edinburgh Castle and my daughter Morgenstern was very keen I should put in a showing…

So here I am helping to herd 5-year olds through the military museum. Morgenstern is nowhere in sight, but little Harry has latched onto me.

“Oh,” says Harry. He copies my mime and sprays the room. “Bang bang bang bang bang bang bang bang bang bang bang bang bang.”

“Not like that,” I say. “Three round bursts or you’ll run out of bullets. Plus the thing pulls up.” I mime. “So like this: Bang bang bang!… Bang bang bang!”

Solemnly, Harry discharges three imaginary bullets. “Bang bang bang!”

“Right,” I say, “Now, the other side have guns too. You have to use cover… better if you have a hand grenade, of course.”

His blue eyes widen. “What’s a hand grenade?”

So together we have a great time clearing each gallery with imagined grenade, automatic fire and bayonet.

Later on the way back to the bus Harry says, “My Daddy says wars are bad because people get killed…”

Yes, I had in fact spent the afternoon teaching (my best recollection of) World War Two house clearing tactics to the son of a local clergyman and peace activist.

January 5, 2014

Infamous Edinburgh bodysnatchers’ final five victims?

If you’ve ever visited Edinburgh, you’ll probably have heard about the sinister pairing of Burke and Hare, the bodysnatchers who murdered 16 people and sold the bodies to medical students for dissection. In 2012, five skeletons were uncovered during a townhouse renovation in the Haymarket district, and it’s speculated that the four adults and a child were previously unknown victims:

Archaeologists have only now determined that the five date back to the early 19th century following studies by Historic Scotland and consultants Guard Archaeology.

Altogether around 60 bones were found, including four adult jawbones and others believed to be from a child.

The bodies are thought to be those of criminals or dwellers of the poor houses. Those that were not claimed were frequently used for either dissection, to be anatomical skeletons, or both.

Irish immigrants William Burke and William Hare murdered 16 people in Edinburgh in 1828 and sold the bodies as dissection material, but it is thought unlikely that the pair were responsible for the five found in Grove Street as the notoriety of their crimes means that all their victims are believed to have been accounted for.

John Lawson, from the Edinburgh City Council Archaeology Service, was the first to examine the remains on site.

He said: “At the end of the Enlightenment period there was significant demand for cadavers and which indeed outstripped supply, and that led to a thriving illegal trade, with Burke and Hare clearly the most infamous of those who supplied bodies to medical schools.

“We can’t rule out that those found on Grove Street were sold by the resurrectionists, as they were called, although it might be a stretch to say it was Burke and Hare themselves, given their crimes are well-documented.”

He said that most would be used for dissection, with the skeletons of others used to teach anatomy to students.

But Lawson said it was still unclear why they would have been buried in the garden.

This is a good example of the division of work in the newsroom: the headline says the bodies are linked to Burke and Hare, while the article itself quotes an expert saying it’s “a stretch” to say that. Headlines are usually written by editors, rather than the journalists who put the stories together.

March 29, 2012

Edinburgh may be killing the cultural golden goose

Tiffany Jenkins talks about the origins of the world famous Edinburgh Fringe Festival and the powers-that-be who seem to be determined to strangle it with red tape:

In 1947, eight theatre groups turned up to perform at the newly formed Edinburgh International Festival, an annual event established to celebrate and enrich postwar European cultural life. The theatre groups had not been invited, and were not part of the official programme. So instead they created a spontaneous festival on the side. Growing year on year, with the theatre groups encouraging others to participate, this alternative to the Edinburgh International Festival eventually established itself, in 1959, as the Festival Fringe Society.

Today, Scotland is home to some of the top cultural events in the world. Many take place in Edinburgh during the August months, attracting high-profile authors, artists, comics and theatre companies from all over the globe. At the heart of this cultural firmament is the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, an event now funded and supported by government and local councils. Yet, in a nasty twist, those very same central and local authorities, currently enjoying the prestige of being associated with a world-renowned festival of culture, are seemingly intent on stifling the spontaneous, do-it-yourself impulse that originally gave birth to the Fringe.

[. . .]

From 1 April 2012, it will become necessary to have a ‘Public Entertainment License’ to undertake any kind of public art in Scotland. Previously a licence was only required for events charging admission. Starting next month, even the smallest local events being run for free — say in a café or a bookshop — will require one, which must be applied for six weeks beforehand. This will include exhibitions in temporary places, gigs in record shops, free film screenings, music in pubs. You know, even really dodgy stuff — like poetry readings to 10 men and a dog.

Apart from the form-filling and curtailment of spontaneity — you cannot just ring around a few friends and suggest a performance at the weekend — this will cost money too. In the past, fees for a ‘public entertainment licence’ have ranged from £120 to £7,500, requiring several months’ notice to be given to the council and three weeks public notice. Nothing will happen without long-term planning. Small venues, like cafes, which support artists and performers by hosting free events, won’t be able to cover the costs. And they shouldn’t have to. Art doesn’t need a licence, and nor do we to enjoy it.

What we are seeing is the hyper-regulation of everyday life where anything we choose to do spontaneously and between ourselves is seen as dangerous or threatening. The authorities want to monitor, codify and regulate the most normal, everyday interactions and behaviour.

January 10, 2012

Scottish independence on the front-burner

An interesting summary of the independence debate in Scotland from The Economist:

Put up or shut up. That is the risky (but arguably rather canny) message that David Cameron has sent to the pro-independence head of the Scottish devolved government in Edinburgh, Alex Salmond. Specifically, Mr Cameron has announced that the British government and Westminster Parliament are willing to give Mr Salmond the referendum on Scotland’s future that he says he wants — as long as it is a proper, straight up-and-down vote on whether to stay in the United Kingdom or leave, and is held sooner rather than later.

It is not that Mr Cameron wants to break the three hundred year old union between London and Edinburgh. Both emotionally and intellectually, he is fiercely committed to the union as a source of strength for both Scotland and Britain, insist Conservative colleagues who have discussed the question with him. Publicly, he has pledged to oppose Scottish independence with “every fibre” of his being.

But Mr Cameron and his ministers also feel that Scotland has been drifting in a constitutional limbo, ever since Mr Salmond’s Scottish National Party (SNP) won an outright majority at Scottish parliamentary elections in 2011 (a feat that was supposed to be impossible, under the complex voting system used in Scotland). The SNP campaigned on a simple manifesto pledge to hold a referendum on the future of Scotland. But after his thumping win Mr Salmond slammed on the brakes and started talking about holding a consultative vote in the second half of his term in office, ie, some time between 2014 and 2016.