Feral Historian

Published 22 Aug 2025Science fiction is full of depictions of global superstates and beyond, depictions of humanity as a single unified people. Is this possible? And if so, what might a viable world state actually look like? Or is it all just the fever dream of dirt-league Stalins? Join Damo and myself for a two-part discussion of the inevitability, possibilities, and acceptability of a world state.

00:00 Intro

03:32 A Story of War

09:08 Us and Them

10:52 Culture

17:24 Federation and Nationalism

22:03 Reminders from the ComBloc

23:45 The World State We HaveCheck out Damo’s take • Is a World State…inevitable? Damien Walt…

(more…)

January 14, 2026

Is a World State Inevitable? Feral Historian vs Damien Walter

March 22, 2025

QotD: The Dunbar Number in the ivory tower

As we know, college people are all Leftists, and if Leftists were capable of seeing the skull-fuckingly obvious consequences of their actions, they wouldn’t be Leftists. But I think it’s actually more basic than that. The answer, I submit, involves the Dunbar Number [link], which I’m using as a stand-in for the network of personal relationships that defines any bureaucracy.

Leave your logical brain aside for a second — I’ll pause, to let you pound as many shots as necessary — and think like a chick. Declining enrollment numbers are just a line on a graph. Indeed, the students themselves are mostly an abstraction — professors hate teaching and avoid it whenever possible, which, thanks to grad students, research sabbaticals, and the like, is fairly often. But that radical-even-by-academic-standards lesbian? She’s right there. All the time.

If you’ve never been inside the ivory gulag, it’s hard to convey just how tiny and all-encompassing that world is, but I’ll try. Imagine you’re just out of school and living with two roomies (for the one or two young folks who might still remain among the readership: It was once considered a good thing to move away from home, so much so that even if they had the opportunity to live in Mom’s basement after graduation — even if it would make great financial sense to do so — young folks would endure quite a bit of deprivation in order to make their own way in the world. This often necessitated living in crappy apartments in a dodgy part of town with one or more roommates, for several years). Your roomies do what young guys do — sometimes their girlfriends move in; sometimes they move out; sometimes their friends crash on the couch — but here’s the kicker: Everyone involved does the same job at the same company, such that you’re effectively always at work. Anything you do at “home” gets brought into the office, because everyone you live with — and everyone you could potentially ever live with — is there.

Imagine living life like that. That’s the ivory tower.

Severian, “The Dunbar Problem”, Founding Questions, 2021-10-06.

March 7, 2025

QotD: Infantry combat and esprit de corps

What about the personal relationships that are formed in the context of conflict? Surely, the “band of brothers” is a truly universal experience, right (but note on the complexities of Shakespeare’s Henry V)? Surely the social bonds that held Easy Company together in 1944 and 1945 are the same as those from 1415? Or 415?

Well, no. Not quite.

We can approach this question through the idea of cohesion – the moral force that holds a group of combatants together on the battlefield under the intense emotional stresses of combat. The intense bonds that soldiers form in modern armies (particularly those in the European pattern) are not an accident, but a core part of how those armies, institutionally, seek to build cohesion. [W]e discussed briefly the emergence of the extensively drilled and disciplined “mechanical” soldier of Early Modern Europe, noting that this approach wasn’t necessary for the effective use of firearms (the Ottoman Janissaries, for instance, were quite good with firearms, but were not trained and organized in this way), but rather was a product of elite aristocratic (read: officer) disdain for their up-jumped peasant soldiers and thus the assumption by those aristocrats that the only way to get such men to fight effectively was to relentlessly drill them.

Now the funny thing about this system is that it clearly worked, but not for the reasons its aristocratic pioneers believed. It was only really after the Second World War that systematic study began to be made of unit cohesion (e.g. S.L.A. Marshall, Men Against Fire (1947), though subsequent literature on the topic is voluminous and Marshal’s work has its problems, but its conclusions are broadly accepted having been confirmed in subsequent studies) [NR: Some discussion on Marshall and his theories here]. What emerged quite clearly was that it wasn’t “the cause” or patriotism that held troops together under fire, but group cohesion born out of an intense need not to let fellow soldiers in the unit down. In short, what held units together and made them fight more effectively was (in part, there are many conclusions in Men Against Fire) the strong social bonds between comrades.

And, in fact, the drill and discipline of early modern European armies unintentionally did quite a lot of cohesion building things. Soldiers were removed from civilian society (isolation from larger groups builds unit cohesion), split into very small groups (keeping the core group that coheres below Dunbar’s number aids in group cohesion; thus why the platoon is a natural unit size) and then pushed through difficult and unpleasant training (that drill and discipline) creating a sense of unique shared experience and sacrifice. All of which doesn’t render men machines, but it does create strong social bonds within the units that will keep the men fighting even when they care little for their cause (which they generally did in this period; one does not find a super-abundance of patriotism among, say, the Army of Flanders).

And there is a tendency to point to this cohesion, its modern source in “toughening” boot camp and to say, “aha! That is the true universal about effective soldier-warriors!” Except – and you knew there was going to be an except – except it isn’t. Systems built on the use of drill and discipline for the development of unit cohesion through social bonds are actually, historically speaking, quite rare. We see systems like that in use by the Romans from the Middle Republic forward (but significantly faded by the end of late antiquity; the Byzantine army doesn’t seem to function this way), in China from the Han Dynasty onward, in Japan for the ashigaru infantry from the Sengoku period, and in Europe from the Early Modern period. That sounds like a lot, but that is relatively small minority of the historical period and even then in a relatively small minority of places. It is, for instance, a period that only covers about half of the historical period in Western Europe, the place most often associated with this very system of organization (though that association is perhaps unfair to East Asia).

Instead, most societies relied on existing social bonds formed outside of the experience of war for cohesion. Greek hoplite armies, for instance, generally formed up by polis (read: city) and then within those blocks by still smaller and smaller social divisions, so that family and neighbors would be standing shoulder to shoulder in the battle line (Sparta does this through the system of communal messes, the syssitia, but the idea that you fought alongside the men you dined with socially – your neighbors, generally – was perfectly normal in most Greek cities). That was intentional – it allowed the phalanx to cohere through the social pressure not to be seen as a coward before the men who meant the most to you, whose shaming gaze you would have to endure in civilian life. The same pressures, by the well, held together the (mostly volunteer) armies of the American Civil War (on this, see, McPherson, For Cause and Comrades (1997)).

By contrast, “warrior” classes often rely on a sort of class solidarity along with the demand of an individual military aristocrat to be individually militarily excellent. Richard Kaeuper quips of the literature of the medieval knightly class that it was filled with “utterly tireless, almost obsessional emphasis placed on personal prowess” (R.W. Kaeuper, Chivalry and Violence in Medieval Europe (1999)). We’ve talked a fair bit about the values of mounted aristocrats, both in their role as combatants and in their roles as generals and those values are relatively disconnected from discipline-induced forms of buddy-cohesion. Of course exactly what “good generalship” or “good officership” looks like varies wildly from place to place – Alexander was expected to command his cavalry from the front; Roman emperors rarely took the battlefield and when they did they commanded from the rear since it would be foolish to risk the “brain” of the army in personal combat and in any event someone at the front of a cavalry charge can hardly direct the rest of the army.

One of the things I find most striking about the “warrior ethos” advanced by writers like Pressfield is that it accepts as normal the unique nature of the bonds that hold soldiers together in battle, assuming this bond and its shared sacrifice to be at once unique to combat and also transcendent to all combatants. But one of the key points made very well in Sebastian Junger’s War (2010) and later Tribe (2016) is just how strange that experience is, historically. Junger notes that in earlier societies, soldiers would have returned from war into communities (often small, agricultural communities or tribal communities) every bit as close-knit as the infantry platoon – and indeed, often involving literally the same people as the infantry platoon. Instead, the intense feeling of uniqueness that modern soldiers feel about the bonds of combat is because of the historically unusual deracination produced by modern societies by the industrial revolution and the post-industrial period.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Universal Warrior, Part IIb: A Soldier’s Lot”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-02-05.

December 12, 2023

QotD: “Natural hierarchies” don’t work in distributed systems

This, I think, is a function of something like the Dunbar Number. There IS a “natural hierarchy”, but it only works in person – that is, in a group where everyone interacts face to face. Any given group of humans will naturally sort itself, and again, yeah yeah, I’m not a biologist, but I’ve been to a few bars in my time. If you doubt it, just head down to your local dive and pilot a barstool for a few hours, you’ll see enough basic primate behavior to give Jane Goodall a stiffie.

Politics, being a distributed system, doesn’t work like that. Neither does the corporate world, which is why both invariably end up dominated by sociopathic, sexually deviant shitweasels. Whereas the social interaction in a bar, in a pickup basketball game, in a church group, whatever, naturally bends towards a baboon troop, “social” interaction in a distributed power structure bends towards whoever has the time, energy, and sheer Wille zur Macht, as our friend above would put it, to dominate it.

Example: Even at the height of his power, when he really could have liquidated everyone in the room with a wave of his hand, Joe Stalin didn’t win arguments with his nomenklatura by threatening to have them all shot. Rather, he outworked them. Even when he exercised the most raw power any one human being is capable of wielding, Stalin’s work ethic was legendary – he spent a minimum of fifteen hours a day at his desk, every day, 365 days a year. He simply ground down all lesser men with the sheer force of his leather ass and cast-iron bladder … and compared to Stalin, when it came to paperwork, all men were lesser men.

That’s a cast of mind, reinforced by the habits of a lifetime. Stalin was also a dominant personality by the end, of course, but he certainly didn’t start that way – he was cringingly servile to Lenin, for instance, and even once to Trotsky, which is probably the main reason Trotsky had to die when you come right down to it.

Hitler was the same way, in his own special, bizarre way. While no one would ever accuse Hitler of an overactive work ethic when it comes to government – those who study these things still can’t get their heads around it, the fact that for long, critical periods the Third Reich basically didn’t have a government – but he could wear you down with the best of them when it came to party speeches, organizing, propaganda. No one worked harder at that stuff than Corporal Hitler … and no one knuckled under to authority faster, which is why he remained Corporal Hitler despite four years on the Western Front.

Combine them, and you get the Big Man On Campus thoroughly dominated by the deviant sociopathic shitweasels. The BMOC dominates every personal interaction; therefore, he thinks it’s the rules which get him where he is. Society is set up, he thinks, to produce people such as himself. And since that society is also set up such that the deviant sociopathic shitweasels (we should probably acronymize that; hereafter, DSS) do the boring shit like student government, when the DSS pass some bizarre law the BMOC just rolls with it …

Severian, “Bio-Marxism Grab Bag”, Founding Questions, 2021-01-21.

January 31, 2023

“Thorstein Veblen’s famous ‘leisure class’ has evolved into the ‘luxury belief class'”

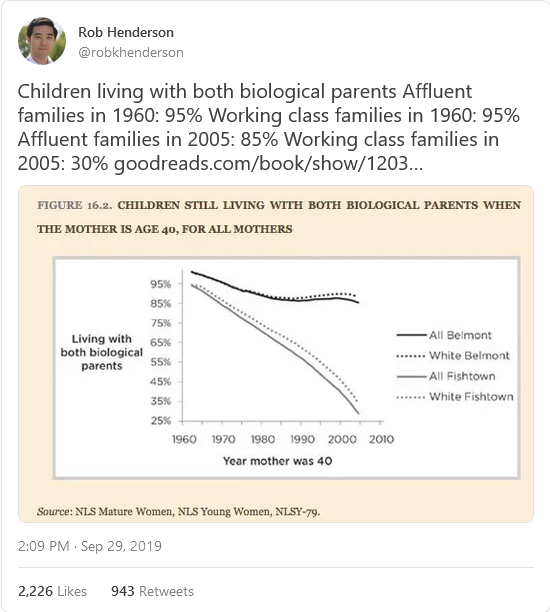

Rob Henderson had a particularly difficult childhood, but thanks to his own efforts ended up going to Yale after leaving the military. He discovered a very different world when he began his studies:

I was bewildered when I encountered a new social class at Yale four years ago: the luxury belief class. My confusion wasn’t surprising given my unusual background. When I was three years old, my mother was addicted to drugs and my father abandoned us. I grew up in multiple foster homes, was then adopted into a series of broken homes, and then experienced a series of family tragedies. Later, after a few years in the military, I went to Yale on the GI Bill. On campus, I realized that luxury beliefs have become fashionable status symbols. Luxury beliefs are ideas and opinions that confer status on the rich at very little cost, while taking a toll on the lower class.

In the past, people displayed their membership in the upper class with their material accoutrements. But today, luxury goods are more affordable than before. And people are less likely to receive validation for the material items they display. This is a problem for the affluent, who still want to broadcast their high social position. But they have come up with a clever solution. The affluent have decoupled social status from goods, and re-attached it to beliefs.

[…]

You might think that rich students at elite universities would be happy because they are in the top 1% of income earners. But remember, they’re surrounded by other members of the 1%. Their social circle, their Dunbar number, consists of 150 baby millionaires. Jordan Peterson has discussed this phenomenon. Citing figures from his experience teaching at Harvard in the 1990s, Peterson noted that a substantial proportion of Ivy League graduates go on to obtain a net worth of a million dollars or more by age 40. And yet this isn’t enough for them. Not only do top university graduates want to be millionaires-in-the-making, they also want the image of moral righteousness. Elite graduates desire high status not only financially, but morally as well.

For our affluent social strivers, luxury beliefs offer them a new way to gain status.

Thorstein Veblen’s famous “leisure class” has evolved into the “luxury belief class”. Veblen, an economist and sociologist, made his observations about social class in the late nineteenth century. He compiled his observations in his classic work, The Theory of the Leisure Class. A key idea is that because we can’t be certain of the financial standing of other people, a good way to size up their means is to see whether they can afford to waste money on goods and leisure. This explains why status symbols are so often difficult to obtain and costly to purchase. These include goods such as delicate and restrictive clothing, like tuxedos and evening gowns, or expensive and time-consuming hobbies like golf or beagling. Such goods and leisurely activities could only be purchased or performed by those who did not live the life of a manual laborer and could spend time learning something with no practical utility. Veblen even goes so far as to say, “The chief use of servants is the evidence they afford of the master’s ability to pay.” For Veblen, butlers are status symbols, too.

Converging on these sociological observations, the biologist Amotz Zahavi proposed that animals evolve certain displays because they are so costly. The most famous example is the peacock’s tail. Only a healthy bird is capable of growing such plumage while managing to evade predators. This idea might extend to humans, too. More recently, the anthropologist and historian Jared Diamond has suggested that one reason why humans engage in displays such as drinking, smoking, drug use, and other physically costly behaviors, is because they serve as fitness indicators. The message is “I’m so healthy that I can afford to poison my body and continue to function.” Get hammered while playing a round of golf with your butler, and you will be the highest status person around.

December 30, 2021

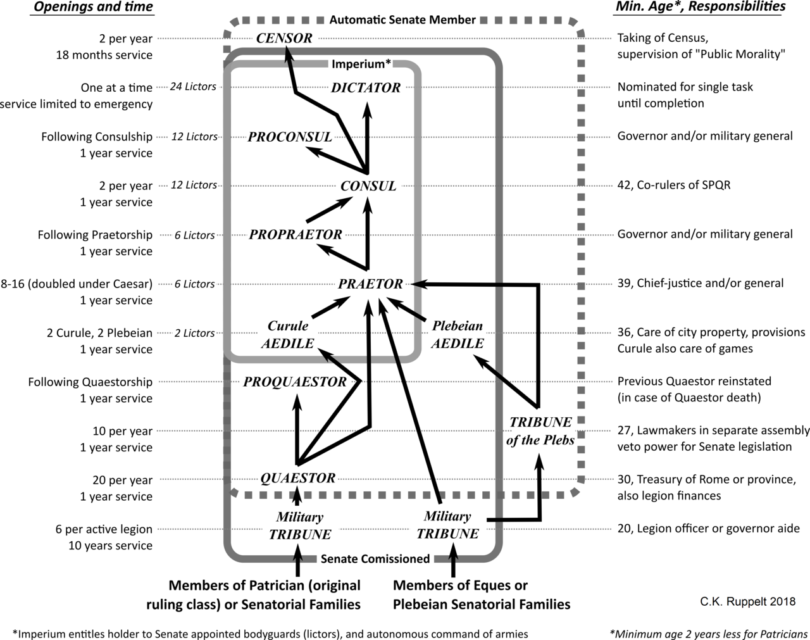

The Cursus Honorum of the late Roman Republic

At Founding Questions, Severian notes that the Cursus Honorum — the formal “career path” for ambitious men in the late Roman Republic was a remarkably effective process … that ended up being a victim of its own success:

Ahhh, God bless the autists at Wiki, they’ve got it down to a chart:

This is from Caesar’s time, and since one of this blog’s main themes is the confusion between process and outcome, let’s put it right up front: This system, the cursus honorum, was designed to produce men like Julius Caesar …

… and you can take that in either sense.

Caesar is one of the most mulled-over men in history, but nobody seriously doubts that he was at least competent at pretty much everything. Maybe he didn’t make the big list of “Greatest Pontifices Maximi” (or however the Latin goes), but he wasn’t a disgrace to the toga, either. If it was a public function in the Late Roman Republic, Caesar was at least decent at it.

And that’s what the cursus honorum was designed to do. It was a three-fer: It gave you competent public officials, but it also gave young ruling class men some seasoning. Most importantly, it was a way of nurturing talent that also hedged against the Peter Principle. If you want to argue that that makes it a four-fer, go nuts, but the point is, it was a pretty good system … up to a point, and if you’re a regular reader, you know what that point is: The Dunbar Number, at which point relationships become too complex to be managed personally, and bureaucratic structures replace them.

One wishes later governments had something like this — if a guy starts out as a quaestor and discovers he can’t handle it, he’ll bring that knowledge with him to the Senate. (Of course, if he can’t even manage to get elected to that, he’ll know full well his level of talent, and he’ll sit down and shut up on the Senate’s back benches). Note too that the bottom rung is military service — since at that time legionaries were all militia, the voters got a good look at you where it really matters, right from the beginning.

By the time a man reaches the top, then, he has intimate experience of ALL the public offices. Not only that, but he’s well known to everyone who matters, since in between the various offices he’s in the Senate, making connections (or out in the provinces, making other — but no less valuable — connections). A consul, then, is pretty much by definition omnicompetent. He did a good enough job in all the previous public offices that he didn’t disqualify himself for the top slot. Also, he’s been thoroughly vetted — everyone who matters, at pretty much every level of society, has had a good look at him (or, at worst, has a good friend who has had a good look at him).

Obviously it wasn’t a perfect system. Rome had her share of inept consuls, because people are people and sometimes “promotion to your level of incompetence” means “promotion to the very top job”. But for the most part it worked well, and even if a guy turned out to be a dud as consul, well, what can you do? Everyone had at least a reasonable expectation that he’d be able to handle it, which is pretty much the best one can consistently achieve in human affairs. Not only that, but because of the candidate’s long experience and careful vetting, you had a much better than average chance of getting a real winner …

… a man like Caesar, who is at minimum competent at everything, and outstanding at lots of things.

May 6, 2021

QotD: Bureaucracy and “Dunbar’s Number”

Dunbar’s number is a suggested cognitive limit to the number of people with whom one can maintain stable social relationships — relationships in which an individual knows who each person is and how each person relates to every other person … By using the average human brain size and extrapolating from the results of primates, [Dunbar] proposed that humans can comfortably maintain 150 stable relationships.

Wikipedia

Let’s stipulate that the “leader” of a “Dunbar Group” can effectively manage ALL of the group’s affairs. In our hypothetical community, “Dunbarville” (note that we’re doing a very Hobbesian “thought experiment” here), our leader – let’s call him Steve – can grasp the essentials of every issue facing the town. He doesn’t need to be an expert without portfolio. He doesn’t have to know all the ins-and-outs of, say, farming to be the effective leader of Dunbarville. However, he has to know that farming is a thing, the basics of how it’s done, understand the importance of well-maintained farms to the community, etc. Steve can delegate the management of Dunbarville’s kolkhoz to an experienced expert farmer, but Steve knows enough to be able to intervene effectively if the farm expert gets too big for his overalls.

Now consider what happens if Steve is any good at his job. Because Dunbarville’s kolkhoz is so well-managed, it can support a much larger population than 150. What does Steve do? Well, he knows that a population greater than 150 will be beyond his capacity to handle 100% effectively … but he also knows that forcing population restrictions on Dunbarville is the fastest way to get himself exiled, after which they’re going to have a baby boom anyway, so Steve does the best he can. In a few years he’s operating at 90% efficiency, then 70%, then 55%, because the community is simply growing too large for any one man to handle.

Now he has to delegate, and the delegation has to be permanent. Steve simply can’t keep up with everything that’s going on in the kolkhoz. So he delegates “kolkhoz management” to Gary. Gary’s not a bad guy – in fact, he’s the dude who managed the kolkhoz so well in the first place. But that task is, itself, now too big for even Gary to handle, so Gary hires some assistants. Worse, Gary knows he’s getting on in years, so to make sure the kolkhoz will keep working at peak, baby-boom-causing efficiency even after he’s gone, he sets up the Gary School of Farm Management …

And so forth, you get the point, we don’t have to run through the whole thing. That’s what I mean by “irreducible complexity” (IC). Once you clear the Dunbar Number, certain tasks have to be independently managed by cadres of experts who are only nominally answerable to the central authority. That’s where bureaucrats come in, and that’s where bureaucrats are good. Steve can’t manage ALL of Dunbarville’s affairs anymore, since it’s now a bustling community of 1,500, but he can manage the 150 bureaucrats who report to him. And since those bureaucrats are supervising only 150 people themselves …

Bureaucrats are, in effect, the re-imposition of a Dunbar Number on an increasingly complex society. When I say that the Roman Empire, for example, was under-bureaucratized, that’s what I mean. Maybe the Emperor had the good sense to limit his high officials to 150, but they had to manage 400 lower officials each, and each of those 400 were responsible for 20,000 peasants, or whatever the numbers actually were. That’s “irreducible complexity,” org-charts version. Unless you’ve got a perfectly balanced ratio of managers to managed, things are going to get very fuzzy at the edges, very fast … and that’s of course assuming complete competence on everyone’s part.

Severian, “Anticipations and Objections (I)”, Founding Questions, 2020-12-16.

February 22, 2020

QotD: Veblen’s “leisure class” evolve into the “luxury belief class” in truly affluent cultures

You might think that, for example, rich kids at elite universities would be happy because their parents are in the top one per cent of income earners. And they will soon join their parents in this elite guild. But remember, they’re surrounded by other members of the one per cent. Their social circle, their Dunbar number, consists of 150 baby millionaires. Jordan Peterson has discussed this phenomenon. Citing figures from his experience teaching at Harvard in the 1990s, Peterson noted that a substantial proportion of Ivy League graduates go on to obtain a net worth of a million dollars or more by age 40. And yet, he observes, this isn’t enough for them. Not only do top university graduates want to be millionaires-in-the-making; they also want the image of moral righteousness. Peterson underlines that elite graduates desire high status not only financially, but morally as well. For these affluent social strivers, luxury beliefs offer them a new way to gain status.

Thorstein Veblen’s famous “leisure class” has evolved into the “luxury belief class.” Veblen, an economist and sociologist, made his observations about social class in the late nineteenth century. He compiled his observations in his classic work, The Theory of the Leisure Class. A key idea is that because we can’t be certain of the financial standing of other people, a good way to size up their means is to see whether they can afford to waste money on goods and leisure. This explains why status symbols are so often difficult to obtain and costly to purchase. These include goods such as delicate and restrictive clothing like tuxedos and evening gowns, or expensive and time-consuming hobbies like golf or beagling. Such goods and leisurely activities could only be purchased or performed by those who did not live the life of a manual laborer and could spend time learning something with no practical utility. Veblen even goes so far as to say, “The chief use of servants is the evidence they afford of the master’s ability to pay.” For Veblen, Butlers are status symbols, too.

Building on these sociological observations, the biologist Amotz Zahavi proposed that animals evolve certain displays because they are so costly. The most famous example is the peacock’s tail. Only a healthy bird is capable of growing such plumage while managing to evade predators. This idea might extend to humans, too. More recently, the anthropologist and historian Jared Diamond has suggested that one reason humans engage in displays such as drinking, smoking, drug use, and other physically costly behaviors is because they serve as fitness indicators. The message is: “I’m so healthy that I can afford to poison my body and continue to function.” Get hammered while playing a round of golf with your butler, and you will be the highest status person around.

Rob Henderson, “Thorstein Veblen’s Theory of the Leisure Class — A Status Update”, Quillette, 2019-11-16.