Feral Historian

Published 15 Nov 2024The first book in S.M. Stirling’s Emberverse series, Dies The Fire yanks modern technology out of the world and sets the stage for a multi-faceted exploration of how distinct cultures emerge from small isolated groups and the profound effect individuals can have the societies that coalesce around them.

00:00 Intro

01:28 Founders

03:37 Desperation

04:51 Flawed Assumptions

07:05 Composites and Rhymes

(more…)

March 30, 2025

Dies the Fire and the Founder Effect

March 25, 2025

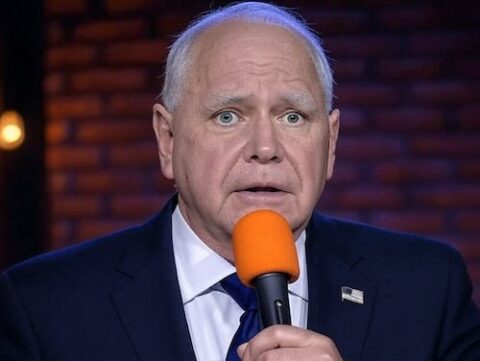

Analyzing the structure of Tim Walz’s “joke”

On his Substack, Jim Treacher shares his deep knowledge of the cultural and linguistic complexities of the humour of Minnesota Governor Tim Walz:

A joke is a delicate thing.

Let’s say you write a joke and then tell it to some people. The joke might “kill” (get a big laugh) with one audience, but then it might “die” (be met with stony silence or outright anger) with another audience.

Maybe you don’t get the wording quite right: “Why did the chicken cross the street? Wait, no …” Maybe the crowd doesn’t understand a reference you’re making. Maybe it’s just not your day. It can take a lot of work to perfect a joke, and any number of things can still go wrong. You’ll fail at least as often as you succeed, and past performance does not guarantee future results.

I’ve never done stand-up comedy because it would require me to leave the house, but I do have a bit of experience writing jokes for television. And sometimes, a joke I thought was funny when I wrote it in the morning just doesn’t land with that evening’s audience. It’s a crummy feeling, but that’s showbiz.

So, I know just how Tim Walz feels these days!

Last week he made a really funny joke, but a lot of people weren’t smart enough to get it because they’re not Democrats […]

I was saying, on my phone, some of you know this, on the iPhone they’ve got that little stock app? I added Tesla to it to give me a little boost during the day. 225 and dropping!

And if you own one, we’re not blaming you. You can take dental floss and pull the Tesla thing off, you know.

Ha ha ha ha ha! [SLAP KNEE, BUST GUT, ETC.]

I will now analyze this brilliant joke, using my hard-won comedy experience, and explain why you’re misguided for not laughing.

You’re welcome.

Now, to the uninitiated, it might sound like Tim Walz is celebrating the misfortune of an opponent. “Ha-ha, your stock is dropping. It’s funny because I don’t like you!” The humor of the bully. Trying to out-Trump Trump.

You might think the audience laughed because they hate Elon Musk so much that they’re happy when he fails, even when it hurts a lot of other people. Maybe even themselves.

But here’s the big twist: That’s not it at all!

See, Governor Walz was being self-deprecating.

When he made that really, really good joke, he already knew that his own state holds 1.6 million shares of Tesla stock in its retirement fund. He was well aware that he was celebrating the misfortune of his own constituents.

But his stage persona didn’t know that.

March 15, 2025

Firefly – We Didn’t Know How Good We Had It

The Critical Drinker

Published 14 Mar 2025It was overlooked in its own time, never finding the audience it deserved, but Firefly has gone on to become a cult classic with the most dedicated on fanbases. And now that I’ve finally arrived to the party 20 years late, I wanted to share my thoughts on Joss Whedon’s Firefly.

March 12, 2025

Free speech in Canada takes yet another hit, as Palestinian activists granted special protections

In the National Post, Tristin Hopper outlines the jaw-dropping contents of the Guide to Understanding and Combatting Islamophobia published by the federal government recently:

The federal government has dropped a new guide that, according to critics, deems it “racist” to criticize Palestinian advocacy or extremism.

The guide also defines both “sharia” and “jihad” as benign terms that are misrepresented by Westerners, with sharia defined as a means “to establish justice and peace in society”.

It’s contained in “The Canadian Guide to Understanding and Combatting Islamophobia“, a document published last week by the Department of Canadian Heritage.

The report endorses the idea of “anti-Palestinian racism”, an activist term with such a broad definition that it technically deems any criticism of Palestinians or “their narratives” to be racist.

“Public discourse often unfairly associates Palestinian and Muslim identities with terrorism,” reads the guide.

The new guide specifically links to a definition of the term circulated by the Arab Canadian Lawyers Association. Their 99-word definition says that it’s racist to link the Palestinian cause to terrorism, to describe it as “inherently antisemitic” or to say that Palestinians are not “an Indigenous people”.

The term is broad enough that merely acknowledging the existence of Israel could fall under its rubric. The definition describes the Jewish state as “occupied and historic Palestine”, and its creation as “the Nakba” (catastrophe). “Denying the Nakba” is specifically cited as one of the markers of “anti-Palestinian racism”.

In a March 4 statement criticizing the new federal report, the Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs (CIJA) said that the term is so vague that “denouncing Hamas – the terrorists behind the October 7 massacre – could be portrayed as an act of racism”.

The new report was praised, meanwhile, by the vocally anti-Israel Centre for Justice and Peace in the Middle East, which called Ottawa’s embrace of the term anti-Palestinian racism “groundbreaking.”

“We are extremely pleased that Canada, through this guide, finally recognizes the unique racism that Palestinians experience daily,” said the group’s acting president Michael Bueckert.

The federal government’s new guide writes that Canada’s “understanding of anti-Palestinian racism” is growing, and directs readers to a 2022 report on the phenomenon by the Arab Canadian Lawyers Association.

March 2, 2025

QotD: Chardonnay

When my editor told me that I could write about anything I wanted in my first column so long as it was Chardonnay, I thought briefly about killing her. In the years since Chardonnay has become a virtual brand name I’ve grown sick to death of hearing my waiter say, “We have a nice Chardonnay”. The “house” chard in most restaurants usually tastes like some laboratory synthesis of lemon and sugar. If on the other hand, you order off the top of the list, you may get something that tastes like five pounds of melted butter churned in fresh-cut oak.

Jay McInerney, Bacchus & Me: Adventures in the Wine Cellar, 2002.

February 9, 2025

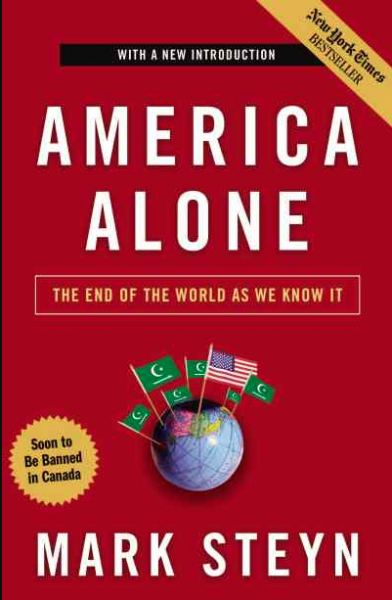

A “certain niche Canadian’s” prophetic look at Western demography

Mark Steyn reminds us that it’s twenty years since he published America Alone: The End of the World as We Know It, which has become more and more accurate every year:

~As some readers may be aware, next year marks the twentieth anniversary of a certain “niche Canadian”‘s boffo international bestseller on demography. So the other day I was musing on whether it was too soon to mark the occasion — only to find I’d been beaten to the punch by the Nigerian media bigfoot Azu Ishiekwene:

It’s nearly 20 years since Mark Steyn wrote a non-fiction book, America Alone: The End of the World as We Know It.

Steyn, a Canadian newspaper columnist, could not have known that the kicker of this book title, which extolled America as the last bastion of civilisation as we know it, would become the metaphor for a wrecking ball.

Steyn thought demographic shifts, cultural decline, and Islam would ruin Western civilisation. The only redeeming grace was American exceptionalism. Nineteen years after his book, America Alone is remembered not for the threats Steyn feared or the grace of American exceptionalism but for an erratic president almost alone in his insanity.

The joke is on Steyn.

Oh, well. It was good while it lasted — which wasn’t as long as it should have, thanks to the dirty stinkin’ rotten corrupt American “justice” system (see below).

~But I thank Mr Ishiekwene for reminding me of the twin theses of my book: on the one hand, “demographic shifts, cultural decline, and Islam” and, on the other, “American exceptionalism”. The first half is undeniable: At one point last year, there were no Anglo-Celtic heads of government anywhere in the British Isles except for Northern Ireland. Nobody even talks about “demographic shifts”, with even “conservative” politicians preferring to focus on “British values” or “French values” or “[Your Country Here] values”, even as those “values”, not least freedom of speech, are remorselessly surrendered. The UK’s “Deputy Prime Minister”, Angela Rayner, is proposing as the state’s reaction to the Southport stabbings, about which the most intemperate Tweeters were less inaccurate than the state propaganda, to restrict free expression even further. Islam? In Britain, Germany, France, the Netherlands, we would rather our children be stabbed and gang-raped than do anything about it, especially if it risks being damned as “Islamophobic”. The delightful Ms Rayner, who once boasted about flashing her soi-disant “ginger growler” across the Commons to Boris Johnson at Question Time, will be keeping it under wraps in the years ahead.

~As for the second part of my book’s arguments — “American exceptionalism” — well, it’s been a rough twenty years. But, to cast Azu Mr Ishiekwene’s contempt for an “an erratic president almost alone in his insanity” in a more generous light, the last three weeks have been a useful reminder that America is still different — or, at any rate, retains the capacity to be different. In his first days in office Trump 47 yanked the US from the World “Health” Organisation and the Paris “climate” accord and the UN “Human Rights” Council. If I have been insufficient in my praise for this energy, it is only because I held out hopes that a man “alone in his insanity” might have simply nuked the WHO. But, such disappointments aside, in Britain (and in the EU it has yet to leave in any meaningful sense), no such decisive acts in the here-and-now can even be contemplated.

And just because I’ve been including a fair bit of USAID-related stuff this week, he comments on Elon Musk’s epic sidequests investigations into US government waste and corruption:

~That’s the good news — and it’s very heartening. The bad news is that almost everything the national government (it is no longer really “federal”) of the United States touches is a racket.

The United States Agency for International Development is so-called in order that gullible rubes who listen to NPR think that it’s something to do with helping starving children in Africa. The cynical rubes who follow Conservative Inc think it’s something to do with helping African dictators’ Swiss bank accounts and endlessly regurgitate the old line about “international aid” taking money from poor people in rich countries to give to rich people in poor countries. But this is the cynicism of the terminally naïve and does a great injustice to the average blood-drenched Somali warlord. As Elon Musk has pointed out, ninety per cent of USAid funds are disbursed in the Washington, DC area. Opponents of that line say, ah, yes, but that’s misleading because some of it then gets passed on outside the Beltway eventually to reach some emaciated Congolese laddie.

Well, I would doubt it. There is no legitimate reason for Bill Kristol and Mona Charen to be receiving any funds from an agency for “international development” — and they surely know it. The least we should expect from them is that they come by their Never Trumpery honestly.

But I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that that 90-10 ratio is pretty standard. The US armed forces account for forty per cent of the planet’s total military spending. Does ninety per cent of that also get disbursed in the District of Columbia? On Thoroughly Modern Milley’s ribbon budget? It’s as good an explanation as any for the failure to win anything since VJ Day. The rube right’s antipathy to foreigners shouldn’t blind us to the fact that the overwhelming majority of the corruption is domestic — and it’s a very bipartisan sewer.

So I wish Trump, Musk et al the best of luck. But, notwithstanding that every rinky-dink District Court judge seems to be labouring under the misapprehension that he’s head of the executive branch of government, Trump has spent the last three weeks doing things. There is no sign that that is even possible in the rest of the west, where the Dutch model seems to prevail: Geert Wilders wins the election, but then gets neutered.

So, in a sense, Azu Ishiekwene is right. There is a yawning chasm between Trump and the poseur attitude-flaunting rest of the west. And yet Mr Ishiekwene is wrong on this: an erratic president is not almost alone in his insanity. In case you haven’t noticed, Panama won’t be renewing its Chinese deal on the Belt & Road Initiative, and El Salvador is happy to gaol anybody Trump sends them. It turns out that the quickest way to solve any international dispute is to threaten the recalcitrant with twenty-five per cent tariffs starting at midnight. If the forty-seventh president doesn’t seem interested in “winning hearts and minds”, it’s because he’s found something more effective.

QotD: Rosé Wine

Anyone who starts analyzing the taste of a rosé in public should be thrown into the pool immediately. Since I am safe in a locked office at this moment, though, let me propose a few guidelines. A good rosé should be drier than Kool-Aid and sweeter than Amstel Light. I should be enlivened by a thin wire of acidity, to zap the taste buds, and it should have a middle core of fruit that is just pronounced enough to suggest the grape varietal (or varietals) from which it was made. Pinot Noir, being delicate to begin with, tends to make delicate rosés. Cabernet, with its astringency, does not. Some pleasingly hearty pink wines are made from the red grapes indigenous to the Rhône and southern France, such as Grenache, Mourvèdre, and Cinsault. Regardless of the varietal, rosé is best drunk within a couple of years of vintage.

Jay McInerney, Bacchus & Me: Adventures in the Wine Cellar, 2002.

January 30, 2025

QotD: Michael Moore

Bowling for Columbine is the latest documentary from Michael Moore, the leftwing multi-millionaire provocateur in his usual cunning disguise as an all-American lardbutt loser — baseball cap, unkempt hair, untucked shirt. This time, the nominal subject is American violence, but, by now, connoisseurs of Roger and Me and Moore’s TV work know that, whatever the subject, the routine never varies: he turns up at company headquarters unannounced and demands to see the chairman. The receptionist says he’s not available, and Moore merrily films the stand-off before moving on to some other target. If he showed up to see me without making an appointment, I’d tell him to piss off and then fire a warning shot. If I showed up to see him unannounced and accompanied by a camera crew, his people would do the same to me.

But most folks are nicer than that.

And so you can’t help noticing that, for a champion of the little guy, he goes to an awful lot of time and effort to make the little guy look like a chump. Moore has no interest in digging deep into his subjects when all the fun’s to be had on the surface of American life — the squeaky receptionists, the bored security guards, the bland PR women, the squaresville company guy in the suit, the State Police trooper with the infelicitous phrasing, the bozo in the pool hall … His vision of America as a wasteland of gun kooks, conspiracy theorists and perky brain-fried mall clerks will doubtless have them rolling in the aisles in Paris this weekend. In my corner of New Hampshire, there were only four other moviegoers in the theater. But Moore, a great favorite with the BBC, now does his shtick with an eye to the non-American market.

Mark Steyn, “Bowling for Columbine”, Steyn Online, 2002-11-30.

January 18, 2025

QotD: On Auguste Rodin’s Fallen Caryatid

“For three thousand years architects designed buildings with columns shaped as female figures. At last Rodin pointed out that this was work too heavy for a girl. He didn’t say, ‘Look, you jerks, if you must do this, make it a brawny male figure’. No, he showed it. This poor little caryatid has fallen under the load. She’s a good girl — look at her face. Serious, unhappy at her failure, not blaming anyone, not even the gods … and still trying to shoulder her load, after she’s crumpled under it.

“But she’s more than good art denouncing bad art; she’s a symbol for every woman who ever shouldered a load too heavy. But not alone women — this symbol means every man and woman who ever sweated out life in uncomplaining fortitude, until they crumpled under their loads. It’s courage, […] and victory.”

“‘Victory’?”

“Victory in defeat; there is none higher. She didn’t give up […] she’s still trying to lift that stone after it has crushed her. She’s a father working while cancer eats away his insides, to bring home one more pay check. She’s a twelve-year old trying to mother her brothers and sisters because Mama had to go to Heaven. She’s a switchboard operator sticking to her post while smoke chokes her and fire cuts off her escape. She’s all the unsung heroes who couldn’t make it but never quit.

Robert A. Heinlein, Stranger in a Strange Land, 1961.

January 13, 2025

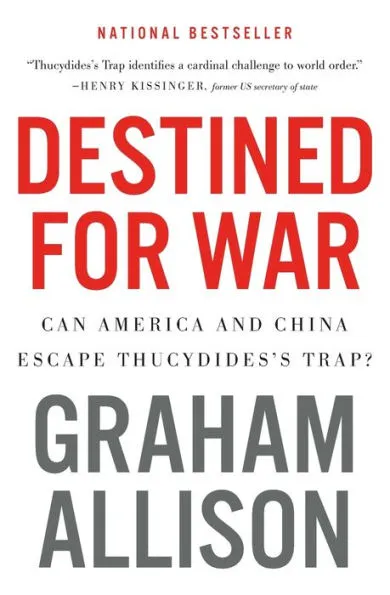

The “Thucydides Trap”

At History Does You, Secretary of Defense Rock provides a handy explanation of the term “the Thucydides Trap”:

In the world of international relations, few concepts have captured as much attention — and sparked as much debate — as the “Thucydides Trap”. Brought to prominence by Harvard political scientist Graham Allison, the term suggests that conflict is almost inevitable when a rising power threatens to displace an established one, a dynamic often invoked to frame the strategic rivalry between the United States and China. Lauded as a National Bestseller and praised by figures like Henry Kissinger and Joe Biden, Allison’s Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap? has become a staple of policy discussions and academic syllabi. Yet beneath the widespread acclaim lies a deeply flawed analysis, one that risks oversimplifying history and perpetuating a fatalistic narrative that could shape policy in dangerous ways. Far from an inescapable destiny, the lessons of history and the nuances of modern geopolitics suggest that the so-called “trap” may be more myth than inevitability.

The term “Thucydides Trap” is derived from a passage in the ancient Greek historian Thucydides’ work History of the Peloponnesian War, where he explained the causes of the conflict between Athens (the rising power) and Sparta (the ruling power) in the 4th century BC. Thucydides famously wrote

It was the rise of Athens and the fear that this instilled in Sparta that made war inevitable.

Allison defines the “Thucydides Trap” as “the severe structural stress caused when a rising power threatens to upend a ruling one”.1 More articles by Allison using this term previously appeared in Foreign Policy and The Atlantic. The book, published in 2017, was a huge hit, being named a notable book of the year by the New York Times and Financial Times while also receiving widespread bipartisan acclaim from current and past policymakers. Historian Niall Ferguson described it as a “must-read in Washington and Beijing”.2 Senator Sam Nunn wrote, “If any book can stop a World War, it is this one”.3 A brief search on Google Scholar reveals the term “Thucydides Trap” has been cited or used nearly 19,000 times. In 2015, Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull even publicly urged President Xi and Chinese Premier Li Keqiang to avoid “falling into the Thucydides Trap”.4 One analyst observed that the term had become the “new cachet as a sage of U.S.-China relations”.5 The term has become so prominent that it is almost guaranteed to appear in any introductory international politics course when discussing U.S.-China relations.

Allison wrote in his essay “The Thucydides Trap: Are the U.S. and China Headed for War?” in The Atlantic published in 2015, “On the current trajectory, war between the United States and China in the decades ahead is not just possible, but much more likely than recognized at the moment” forewarning, “judging by the historical record, war is more likely than not”.6 A straightforward analysis of the 16 cases in the book and previous essays might indicate that, based on historical precedent, there is approximately a 75 percent likelihood of the United States and China engaging in war within the next several decades. Adding the additional cases from the Thucydides Trap Website would still leave a 66 percent chance, more likely than not, that two nuclear-armed superpowers will go to war with one another, a horrifying and unprecedented proposition.7

With such alarm, it’s no surprise that the concept gained such widespread attention. The term is simple to understand and in under 300 pages, Allison delivers a sweeping historical narrative, drawing striking parallels between events from ancient Greece to the present day.8 International Relations as a field often struggles to break through in the public discourse, but Destined for War broke through, making a broad impact on academic and popular discourse.

1. Graham Allison, Destined For War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap? (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017), 29.

2. Ibid., iii.

3. Ibid., vi.

4. Quoted by Alan Greeley Misenheimer, Thucydides’ Other “Traps”: The United States, China, and the Prospect of “Inevitable” War (Washington: National Defense University, 2019), 8.

5. Misenheiemer, 1.

6. “Thucydides’s Trap Case File” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School, accessed December 31, 2024

7. Graham Allison, “The Thucydides Trap: Are the U.S. and China Headed for War?” The Atlantic, September 24, 2015.

8. Misenheimer details what Thucydides actually said about the origins of the Peloponnesian War, 10-17.

January 5, 2025

German democracy hanging by a thread after vicious attacks by Elon Musk

German politicians are growing ever more desperate as evildoers like Elon Musk continue to undermine the political stage by calling for antidemocratic things like free speech:

Alice Weidel, the federal leader of Germany’s “far-right” AfD, has approximately the same policy prescriptions as Donald Trump. Chiefly they are to return to the bourgeois habits that used to make free market states prosperous. But she subscribes to these in mainland Europe, which has been easily spooked since the Nazis offered policies that were not bourgeois.

“Humankind cannot bear very much reality,” as the far-right poet, T. S. Eliot, wrote in Burnt Norton, now the better part of a century ago. (He was arguably plagiarizing the far-right German poet, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.)

One could recommend that my readers look her up on YouBoob, or better search for print, and form their own opinion on this Frau Weidel. (Who speaks English, and Chinese, fluently.)

Compare her, for instance, to the British prime minister, Keir Starmer, who rose to power as the prosecutor protecting Muslim “grooming gangs”, and now puts people in gaol who protest on behalf of their rape and murder victims. The idea that Mr Starmer should have a rôle in the government of a civilized country, is as absurd as the idea that the 14-year-old narcissist who has ruled Canada, or the 82-year-old senescent who has ruled the United States, are respectable members of the human race.

And closer to the scene of crisis, eugyppius reports on the latest Muskian outrage against peace-loving German politicians:

For days, the German establishment have been in an absolute uproar over Elon Musk’s profoundly antidemocratic election interference. You cannot turn on the television or open any newspaper without enduring all manner of wailing about the grave danger Musk poses to German democracy.

The naive and the simpleminded will say that all of this is crazy and that the Federal Republic has become an open-air insane asylum – a strange playground of political hysterics the likes of which the Western world has never seen before. That is because they don’t understand what’s at stake here. Musk did not just say the odd nice thing about Alternative für Deutschland, oh no. He also said various German politicians were fools and traitors, he called for resignations and he published an untoward newspaper editorial. It is amazing the German democracy has not yet collapsed in the face of this unrelenting campaign, and still the absolute madman shows no signs of stopping.

Elon Musk’s frontal assault on the German constitution began on 7 November, when he tweeted four antidemocratic words – “Olaf ist ein Narr” (“Olaf [Scholz] is a fool”) – in response to news that the German government had collapsed. Three days later, he tweeted the same thing about Green Economics Minister and chancellor candidate Robert Habeck, after Habeck gave a speech calling for widespread internet censorship.

Thereafter, all was quiet for a time. German democrats allowed themselves to hope these were but isolated indiscretions and that Musk would allow them to get back to their arcane business of promoting feminism abroad, changing the weather and eliminating “the extreme right”. Lamentably, the peace turned out to be a false one. Musk renewed his campaign against democracy with a vengeance on 20 December, tweeting in the wake of the Magdeburg Christmas market attack that “Scholz should resign immediately” and that he is an “incompetent fool”. That very same day, Musk tweeted for the first time that “Only the AfD can save Germany”, a sentiment he repeated also on 21 December and on 22 December, delighted at the nationwide freakout his casual remarks had incited.

In the course of this freakout, German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier hinted darkly that “outside influence” constitutes “a danger for democracy”:

Outside influence is a danger for democracy – whether it is covert, as was recently apparent in the elections in Romania, or open and blatant, as is currently being practised with particular intensity on the platform X. I strongly oppose all external attempts at influence. The decision on the election is made solely by the eligible citizens in Germany.

The indefatigable Naomi Seibt, who appears to be Musk’s primary informant about German politics, brought these remarks to the evil fascist billionaire’s attention, and he promptly responded that “Steinmeier is an anti-democratic tyrant”. Musk then delivered his coup-de-grace the next day, with an editorial in Welt am Sonntag – the most devastating piece of political prose that Germany has witnessed since Hitler penned Mein Kampf.

By my count, Musk may have directed as many as 700 words against the noble if surprisingly rickety edifice of German democracy – an assault few political systems could withstand. The self-appointed guardians of our liberal order accordingly declared a five-alarm fire, and they have betaken themselves to their keyboards to defend what remains of our free and eminently democratic political system, where anybody can say anything he likes and vote for any party he wishes, so long as what he likes and those for whom he votes have nothing to do with major political parties supported by millions of Germans like Alternative für Deutschland.

December 25, 2024

Drinker’s Christmas Crackers – It’s a Wonderful Life

The Critical Drinker

Published 17 Dec 2020Join me as I review what may be the ultimate Christmas movie — the 1946 classic starring James Stewart and Donna Reed … It’s a Wonderful Life.

December 22, 2024

QotD: “Sparta Is Terrible and You Are Terrible for Liking Sparta”

“This. Isn’t. Sparta.” is, by view count, my second most read series (after the Siege of Gondor series); WordPress counts the whole series with just over 415,000 page views as I write this, with the most popular part (outside of the first one; first posts in a series always have the most views) being the one on Spartan Equality followed by Spartan Ends (on Spartan strategic failure). The least popular is actually the fifth part on Spartan Government, which doesn’t bother me overmuch as that post was the one most narrowly focused on the spartiates (though I think it also may be the most Hodkinsonian post of the bunch, we’ll come back to that in a moment) and if one draws anything out of my approach it must be that I don’t think we should be narrowly focused on the spartiates.

In the immediate moment of August, 2019 I opted to write the series – as I note at the beginning – in response to two dueling articles in TNR and a subsequent (now lost to the ages and only imperfectly preserved by WordPress’ tweet embedding function) Twitter debate between Nick Burns (the author of the pro-Sparta side of that duel) and myself. In practice however the basic shape of this critique had been brewing for a lot longer; it formed out of my own frustrations with seeing how Sparta was frequently taught to undergraduates: students tended to be given Plutarch’s Life of Lycurgus (or had it described to them) with very little in the way of useful apparatus to either question his statements or – perhaps more importantly – extrapolate out the necessary conclusions if those statements were accepted. Students tended to walk away with a hazy, utopian feel about Sparta, rather than anything that resembled either of the two main scholarly “camps” about the polis (which we’ll return to in a moment).

That hazy vision in turn was continually reflected and reified in the popular image of Sparta – precisely the version of Sparta that Nick Burns was mobilizing in his essay. That’s no surprise, as the Sparta of the undergraduate material becomes what is taught when those undergrads become high school teachers, which in turn becomes the Sparta that shows up in the works of Frank Miller, Steven Pressfield and Zack Snyder. It is a reading of the sources that is at once both gullible and incomplete, accepting all of the praise without for a moment thinking about the implications; for the sake of simplicity I’m going to refer to this vision of Sparta subsequently as the “Pressfield camp”, after Steven Pressfield, the author of Gates of Fire (1998). It has always been striking to me that for everything we are told about Spartan values and society, the actual spartiates would have despised nearly all of their boosters with sole exception of the praise they got from southern enslaver-planter aristocrats in the pre-Civil War United States. If there is one thing I wish I had emphasized more in “This. Isn’t. Sparta.” it would have been to tell the average “Sparta bro” that the Spartans would have held him in contempt.

And so for years I regularly joked with colleagues that I needed to make a syllabus for a course simply entitled, “Sparta Is Terrible and You Are Terrible for Liking Sparta”. Consequently the TNR essays galvanized an effort to lay out what in my head I had framed as “The Indictment Against Sparta”. The series was thus intended to be set against the general public hagiography of Sparta and its intended audience was what I’ve heard termed the “Sparta Bro” – the person for whom the Spartans represent a positive example (indeed, often the pinnacle) of masculine achievement, often explicitly connected to roles in law enforcement, military service and physical fitness (the regularity with which that last thing is included is striking and suggests to me the profound unseriousness of the argument). It was, of course, not intended to make a meaningful contribution to debates within the scholarship on Sparta; that’s been going on a long time, the questions by now are very technical and so all I was doing was selecting the answers I find most persuasive from the last several decades of it (evidently I am willing to draw somewhat further back than some). In that light, I think the series holds up fairly well, though there are some critiques I want to address.

One thing I will say, not that this critique has ever been made, but had I known that fellow UNC-alum Sarah E. Bond had written a very good essay for Eidolon entitled “This is Not Sparta: Why the Modern Romance With Sparta is a Bad One” (2018), I would have tried to come up with a different title for the series to avoid how uncomfortably close I think the two titles land to each other. I might have gone back to my first draft title of “The Indictment Against Sparta” though I suspect the gravitational pull that led to Bond’s title would have pulled in mine as well. In any case, Sarah’s essay takes a different route than mine (with more focus on reception) and is well worth reading.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: This. Isn’t. Sparta. Retrospective”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-08-19.

December 14, 2024

December 12, 2024

QotD: The “natural cycle” of empire

One of the recurrent concepts in the study of history is that of the “natural cycle”, and its most enticing form is that of “collapse”. The Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire. The Rise and Fall of Feudalism. The Rise and Fall of the British Empire. All of these are, of course, ridiculous oversimplifications.

Arguably the evolution of the British Empire into a Commonwealth of 70-odd self-governing nations, many of them with stable democratic governments, who can all get together and play cricket and have Commonwealth Games (and impose sanctions and suspensions on undemocratic members): cannot be considered much of a “collapse” when compared to say the Inca or Aztec civilisations. Nor can post Medieval Europe be considered a “collapsed” version. Even Rome left a series of successor states across Europe – some successful and some not. (Though there was clearly a collapse of economics and general living standards in these successor states.) The fact that the Roman Empire survived in various forms both East – Byzantium – and west – Holy Roman Empire, Catholic Church, Christendom, etc – would also argue somewhat against total collapse. Still the idea has been popular with both publishers and readers.

Yet the “natural cycle” theory has been revisited recently by economic historians in such appalling works on “Imperialism and Collapse”, as The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers. [That’s the one where the Paul Kennedy explained how US power “has been declining relatively faster than Russia’s over the last few decades” (p.665) – just before the Berlin Wall came down.]

Nigel Davies, “The Empires of Britain and the United States – Toying with Historical Analogy”, rethinking history, 2009-01-10.