Ted Gioia on Paul McCartney’s latest single — his first in several years — and what he’s protesting against … clankers in music and the arts:

Paul McCartney is releasing a new track. It’s his first new song in five years — so that’s a big deal. But there’s something even more significant about this 2 minute 45 second release.

The song is silent. It’s a totally blank track — except for a bit of hiss and background noise.

What’s going on? Has Paul McCartney run out of melodies at age 83? Is he nurturing his inner John Cage. Did he simply forget to turn on the mic?

No, none of the above.

Macca is releasing this track as a protest against AI.

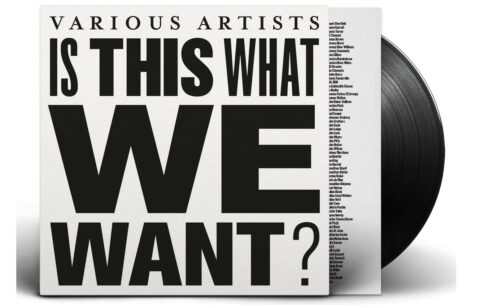

His new “music” is part of an album entitled Is This What We Want? It’s already available on digital platforms, and is now coming out on vinyl. All proceeds will go to the non-profit organization Help Musicians.

“The album consists of recordings of empty studios and performance spaces,” according to the website. In addition to McCartney, more than a thousand musicians are participating, including:

Kate Bush, Annie Lennox, Damon Albarn, Billy Ocean, Ed O’Brien, Dan Smith, The Clash, Mystery Jets, Jamiroquai, Imogen Heap, Yusuf / Cat Stevens, Riz Ahmed, Tori Amos, Hans Zimmer, James MacMillan, Max Richter, John Rutter, The Kanneh-Masons, The King’s Singers, The Sixteen, Roderick Williams, Sarah Connolly, Nicky Spence, Ian Bostridge, and many more.

I keep hearing that protest music is dead — and has been losing momentum since the Vietnam War. But there’s now a new war, and it’s stirring up creators in every artistic idiom.

They are fighting for their livelihoods and IP rights. And, so far, it’s been a losing battle.

You can see the new battle lines across the entire creative landscape.

Vince Gilligan, one of the most brilliant minds in TV, admits that he “hates AI”. He calls it the “world’s most expensive plagiarism machine”. For his new show Pluribus, he has added this disclaimer to the credits:

This show was made by humans.

AI represents the exact opposite of creativity, Gilligan warns. It steals the work of others. So any attempt to legitimize it as a creative tool is built on lies. A bank robber might just as well pretend to be a financier. Or an art forger claim to be Picasso.

[…]

This is the new culture war.

And it’s very different from the old culture war — which was a dim reflection of politics. This new battle is happening inside the culture world itself, and threatens to cut off artists from their own longstanding partners and support systems.

This new culture war will only escalate. The stakes are too high, and artists can’t afford to stay on the sidelines. But they face heavy odds, with the richest people on the planet opposed to their efforts.

How will this battle get decided? It really comes down to the audience. If they prefer AI slop, we will witness the total degradation of arts and entertainment.

I’d like to think that people are too smart to fall for this crude simulation of human creative expression. Who wants to hear a bot sing of love it has never experienced? Who wants a nature poem from a digital construct that exists outside of nature? Who wants a painting made by something with no eyes to see?

Will the public find this charming. Or even plausible? Maybe a few twelve year olds and fools, but not serious people. That’s my hunch.

In any event, we will soon find out.