World War Two

Published 1 Aug 2020Japan needs resources for its seemingly endless war in China, but where to look for them? And who might have a problem with it? Meanwhile in the Soviet Union, Hitler’s forces have been diverted from the Moscow Road, and are on the move in the north and the south.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Or join The TimeGhost Army directly at: https://timeghost.tvFollow WW2 day by day on Instagram @World_war_two_realtime https://www.instagram.com/world_war_two_realtime

Between 2 Wars: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list…

Source list: http://bit.ly/WW2sourcesWritten and Hosted by: Indy Neidell

Director: Astrid Deinhard

Producers: Astrid Deinhard and Spartacus Olsson

Executive Producers: Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson, Bodo Rittenauer

Creative Producer: Joram Appel

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: Indy Neidell

Edited by: Iryna Dulka

Sound design: Marek Kamiński

Map animations: Eastory (https://www.youtube.com/c/eastory)Colorizations by:

– Julius Jääskeläinen – https://www.facebook.com/JJcolorization/

– Norman Stewart – https://oldtimesincolor.blogspot.com/

– Jaris Almazani (Artistic Man) – https://instagram.com/artistic.man?ig…

– Dememorabilia – https://www.instagram.com/dememorabilia/

– Carlos Ortega Pereira, BlauColorizations – https://www.instagram.com/blaucoloriz…

– Olga Shirnina, a.k.a. Klimbim – https://klimbim2014.wordpress.com/

– Daniel WeissSources:

– Mil.ru

– Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe

– Bundesarchiv, CC-BY-SA 3.0 – Bild_101I-265-0024-21A, Bild 146-1976-080-13A

– Yad Vashem 1295/1Soundtracks from the Epidemic Sound:

Gunnar Johnsen – “Not Safe Yet”

Rannar Sillard – “Easy Target”

Johannes Bornlof – “Magnificent March 3”

Fabien Tell – “Break Free”

Brightarm Orchestra – “On the Edge of Change”

Wendel Scherer – “Growing Doubt”

Philip Ayers – “Under the Dome”

Philip Ayers – “Trapped in a Maze”Archive by Screenocean/Reuters https://www.screenocean.com.

A TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

August 2, 2020

July 5, 2020

May 31, 2020

Sink the Bismarck! – The Pride of the Kriegsmarine‘s Demise – WW2 – 092 – May 30 1941

World War Two

Published 30 May 2020This week, the Battle of Crete continues as the Bismarck and Prinz Eugen set sail to the Atlantic, starting one of the most dramatic episodes in the histories of the Royal Navy and the Kriegsmarine.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Or join The TimeGhost Army directly at: https://timeghost.tvFollow WW2 day by day on Instagram @World_war_two_realtime https://www.instagram.com/world_war_t…

Between 2 Wars: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list…

Source list: http://bit.ly/WW2sourcesWritten and Hosted by: Indy Neidell

Director: Astrid Deinhard

Producers: Astrid Deinhard and Spartacus Olsson

Executive Producers: Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson, Bodo Rittenauer

Creative Producer: Joram Appel

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: NN

Edited by: Iryna Dulka

Sound design: Marek Kamiński

Map animations: Eastory (https://www.youtube.com/c/eastory)Colorizations by:

– Norman Stewart – https://oldtimesincolor.blogspot.com/

– Daniel Weiss

– Jaris Almazani (Artistic Man), https://instagram.com/artistic.man?ig…

– Carlos Ortega Pereira, BlauColorizations, https://www.instagram.com/blaucoloriz…Sources:

– Imperial War Museum: A 6152, A 6155, A 3898, IWM A4057, HU 50190, HU 374, FL 2120, E 3464, E 450

– U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph

– Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe

– Drawing of Churchill from Museon

– Battlecruiser Renown shape by Emoscopes from WikimediaArchive by Screenocean/Reuters https://www.screenocean.com.

A TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

May 29, 2020

Der Bismarck: Doomed to Fail? – WW2 Biography Special

World War Two

Published 28 May 2020The Bismarck is without a doubt a force to be reckoned with. But with the Kriegsmarine experiencing an identity crisis throughout the 1930s, the Bismarck‘s design and strategic purpose foreshadow a dramatic ending.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Or join The TimeGhost Army directly at: https://timeghost.tv

Check out our TimeGhost History YouTube Channel: https://www.youtube.com/c/timeghost?s…Follow WW2 day by day on Instagram @World_war_two_realtime https://www.instagram.com/world_war_t…

Between 2 Wars: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list…

Source list: http://bit.ly/WW2sourcesHosted by: Indy Neidell

Written by: Joram Appel

Director: Astrid Deinhard

Producers: Astrid Deinhard and Spartacus Olsson

Executive Producers: Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson, Bodo Rittenauer

Creative Producer: Joram Appel

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: Joram Appel

Edited by: Mikołaj Cackowski

Sound design: Marek Kamiński

Map animations: Eastory (https://www.youtube.com/c/eastory)Colorizations by:

Ruffneck88, Wikimedia Commons

Norman Stewart – https://oldtimesincolor.blogspot.com/Sources:

Bundesarchiv

IWM HU 374, HU 67486, HU 1041, HU 108392, A 6155, D 2373, HU 55631

From the Noun Project: Game by Ecem Afacan, Shield by Nikita KozinSoundtracks from the Epidemic Sound:

Phoenix Tail – “At the Front”

Johannes Bornlof – “The Inspector 4”

Rannar Sillard – “March Of The Brave 10”

Max Anson – “Ancient Saga”

Johannes Bornlof – “Deviation In Time”

Reynard Seidel – “Deflection”Archive by Screenocean/Reuters https://www.screenocean.com.

A TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

May 27, 2020

The Battle to Crack Enigma – The real story of ‘The Imitation Game’ – WW2 Special

World War Two

Published 26 May 2020For the British, breaking the Germans’ seemingly unbreakable codes is one of the most vital battles of the war. If they fail, there is litte to stop the German U-Boats hunting down Allied shipping in the Atlantic.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Or join The TimeGhost Army directly at: https://timeghost.tvFollow WW2 day by day on Instagram @World_war_two_realtime https://www.instagram.com/world_war_t…

Between 2 Wars: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list…

Source list: http://bit.ly/WW2sourcesHosted by: Indy Neidell

Written by: Francis van Berkel

Director: Astrid Deinhard

Producers: Astrid Deinhard and Spartacus Olsson

Executive Producers: Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson, Bodo Rittenauer

Creative Producer: Joram Appel

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: Francis van Berkel

Edited by: Mikołaj Cackowski

Sound design: Marek Kamiński

Map animations: Eastory (https://www.youtube.com/c/eastory)Colorizations by:

Jaris Almazani (Artistic Man), https://instagram.com/artistic.man?ig…

Norman Stewart, https://oldtimesincolor.blogspot.com/

Carlos Ortega Pereira, BlauColorizations, https://www.instagram.com/blaucoloriz…Sources:

Bundesarchiv

Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe

IWM D 23310, A 13709, A 23513

Picture of Enigma G model, courtesy Austin Mills https://flic.kr/p/2bQ9Q

reconstructed bombe machine at Bletchley Park, courtesy Gerald Massey

Picture of Enigma M4 model displayed at Bletchley Park, courtesy Magnus Manske

Picture of John Herivel, courtesy GCHQ

From the Noun Project: Letter by Mochammad Kafi, Desk by monkik, Phone by libertetstudio, person by Adrien Coquet, Letter by Bonegolem, Table by Creative Stall, documents by Johannes Hirsekorn, sitting at desk by IYIKON, Paper by James KopinaSoundtracks from the Epidemic Sound:

Reynard Seidel – “Deflection”

Johannes Bornlof – “The Inspector 4”

Phoenix Tail – “At the Front”

Johannes Bornlof – “Deviation In Time”

Gunnar Johnsen – “Not Safe Yet”

Hakan Eriksson – “Epic Adventure Theme 3”

Howard Harper-Barnes – “London”Archive by Screenocean/Reuters https://www.screenocean.com.

A TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

From the comments:

World War Two

4 hours ago (edited)

Hopefully you’re all staying safe in these difficult times. We’re still marching on so that we can keep all of you entertained when you’re stuck at home. But we can only continue doing so thanks to your ongoing support. Ad revenue has dropped significantly because of COVID, and we rely on your support now more than ever. If you can, please support us on www.patreon.com/timeghosthistory or https://timeghost.tv.Please let us know what other specials you’d like to see. And if you would like to know something about a smaller topic, make sure to submit that as a question for our Q&A series, Out of the Foxholes. You can do that right here: https://community.timeghost.tv/c/Out-of-the-Foxholes-Qs.

Cheers,

Francis

May 24, 2020

Invasion of Crete: a Bloody Mess – WW2 – 091 – May 23 1941

World War Two

Published 23 May 2020Operation Mercury commences as fallschirmjäger airborne troops land on the Greek island of Crete. A bloody and messy battle follows as it turns out to be costly in more ways than one.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Or join The TimeGhost Army directly at: https://timeghost.tvFollow WW2 day by day on Instagram @World_war_two_realtime https://www.instagram.com/world_war_t…

Between 2 Wars: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list…

Source list: http://bit.ly/WW2sourcesWritten and Hosted by: Indy Neidell

Director: Astrid Deinhard

Producers: Astrid Deinhard and Spartacus Olsson

Executive Producers: Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson, Bodo Rittenauer

Creative Producer: Joram Appel

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Edited by: Iryna Dulka

Sound design: Marek Kamiński

Map animations: Eastory (https://www.youtube.com/c/eastory)Colorizations by:

– Julius Jääskeläinen – https://www.facebook.com/JJcolorization/

– Dememorabilia – https://www.instagram.com/dememorabilia/

– Norman Stewart – https://oldtimesincolor.blogspot.com/

– Jaris Almazani (Artistic Man), https://instagram.com/artistic.man?ig…

– Carlos Ortega Pereira, BlauColorizations, https://www.instagram.com/blaucoloriz…Sources:

– Imperial War Museum: A 28473, E 3064E, A 4154, A 4153, A 4149, A 4144, E 3066E, E 3023E, A 4156, E 6066

– Archives municipales de Brest

– Museums Victoria

– Bundesarchiv, CC-BY-SA 3.0: Bild_141-0816, Bild_183-L04232, Bild_101I-166-0527-10A, Bild 101I-166-0527-22 / Weixler, Franz Peter, Bild_183-L19019, Bild 146-1977-115-04, Bild 141-0823, Bild_101I-166-0512-39, Bild_146-1981-159-22, Bild_146-1980-090-34, E 3022EArchive by Screenocean/Reuters https://www.screenocean.com.

A TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

April 16, 2020

The (temporary) return of “dazzle” paint schemes for the Royal Canadian Navy

Well, two RCN ships, if not the entire fleet … Joseph Trevithick reports for The Drive:

HMCS Regina in her dazzle camouflage paint taking part in Task Group Exercise 20-1 in April, 2020.

Canadian Forces photo via The Drive.

Air forces around the world will often give their aircraft specialized paint jobs to commemorate anniversaries and other notable occasions, but it’s far less common to see navies do the same thing with their ships. Recently, however, the Royal Canadian Navy’s Halifax class frigate HMCS Regina recently took part in a training exercise wearing an iconic blue, black, and gray paint job, commonly known as a “dazzle” scheme, a kind of warship camouflage that first appeared during World War I.

At the end of March 2020, Regina, and her unique paint job, had joined HMCS Calgary, another Halifax-class frigate, along with the Kingston-class coastal defense vessel HMCS Brandon and two Orca-class Patrol Craft Training (PCT) vessels, Cougar* and Wolf*, for Task Group Exercise 20-1 (TGEX 20-1) off the coast of Vancouver Island in the northeastern Pacific Ocean. The training continued into the first week of April. TGEX 20-1 was part of Calgary‘s Directed Sea Readiness Training (DSRT) in preparation for that particular ship’s upcoming deployment.

Regina had first emerged in the dazzle scheme in October 2019 ahead of the U.S. Navy-led Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) exercise, a massive naval training event that takes place every two years and includes U.S. allies and partners from around the Pacific region. It reportedly took 272 gallons of paint and cost the Royal Canadian Navy $20,000 to give Regina the dazzle treatment.

The frigate will wear the camouflage pattern until the end of 2020. The Royal Canadian Navy also painted up the Kingston-class HMCS Moncton, which is homeported in Halifax on the other side of the country, in a similar scheme. The paint job on both ships is in commemoration of the 75th anniversary of the end of the Battle of the Atlantic. This refers to the Allied fight to both enforce a naval blockade of Germany during World War II and secure critical maritime supply routes from North America to Europe. The battle officially ended with the surrender of the Nazi regime in May 1945.

* Wikipedia points out that the Orca-class are not formally commissioned ships in the RCN and therefore do not carry the designation “Her Majesty’s Canadian Ship” (HMCS).

March 23, 2020

Naval strategy versus naval tactics in the Battle of the Atlantic

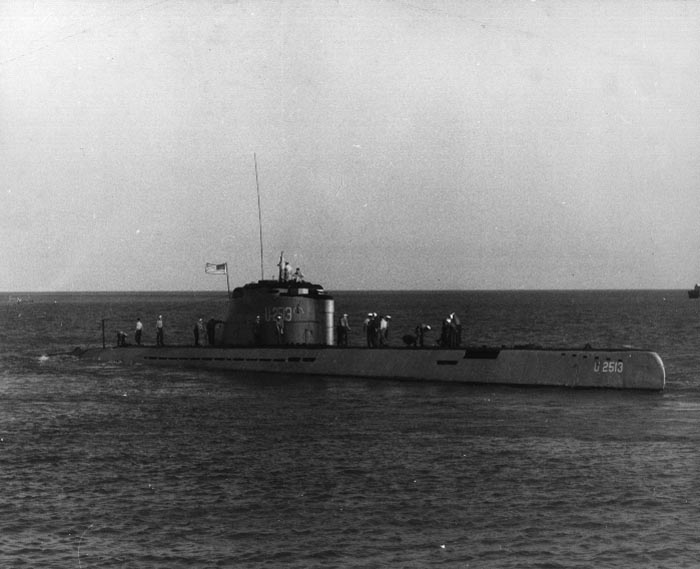

Ted Campbell outlines how the Battle of the Atlantic was fought between the Kriegsmarine and the Royal Navy (and the Royal Canadian Navy and, eventually, the United States Navy) in World War 2:

… there is a rather thick, and quite blurry line between naval strategy and naval tactics. One Army.ca member used the Battle of the Atlantic to distinguish between two doctrines:

- Sea control ~ which was practised by the 2nd World War allies ~ mostly British Admirals Percy Noble and Max Horton in Britain and Canadian Rear Admiral Leonard Murray in St John’s and Halifax; and

- Sea denial ~ which was practised by German Admiral Karl Dönitz.

The difference between the two tactical doctrines was very clear. The strategic aims were equally clear:

- Admiral Dönitz wanted to knock Britain out of the war ~ something that he (and Churchill) understood could be done by starving Britain into submission by preventing food, fuel and ammunition from reaching Britain from North America. (We can be eternally grateful that Adolph Hitler did not share Dönitz’ strategic vision and listened, instead, to lesser men and his own, inept, instincts); and

- Prime Minister Churchill, who really did say that “the only thing that ever really frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril“, who wanted to keep Britain fighting, at the very least resisting, until the Americans could, finally, be persuaded to come to the rescue.

Prime Minister Winston Churchill greets Canadian PM William Lyon Mackenzie King, 1941.

Photo from Library and Archives Canada (reference number C-047565) via Wikimedia Commons.Canada’s Prime Minister Mackenzie King did have a grand strategy of his own. It was to do as much as possible while operating with the lowest possible risk of casualties ~ the conscription crisis of 1917 was, always, uppermost in his mind and he was, therefore, terrified of casualties. He mightily approved of the Navy doing a HUGE share in the Battle of the Atlantic ~ especially by building ships in Canadian yards and escorting convoys which he hoped would be a low-risk affair.

Churchill’s grand strategy was based on Britain surviving … there was, I believe, a “worst case” scenario in which the British Isles were occupied and the King and his government went to Canada or even India. But that has always seemed to me to be a sort of fantasy. The United Kingdom, without the British Isles, made no sense.

(While I believe that Rudolph Hess was, as they say, a few fries short of a happy meal, I think that he and several people in Germany believed that it might be possible to negotiate a peace with Britain which many felt was a necessary precursor to a successful campaign against Russia. The Battle of Britain (die Luftschlacht um England, September 1940 to June 1941) was, clearly, not going in Germany’s favour. Late in 1940, the Nazi high command had been forced to send a German Army formation to Libya to prevent a complete rout of the Italians. Malta still held out, meaning that Britain had air cover throughout the Mediterranean. In short, Britain was not going to go down unless it could be starved into submission ~ and in the spring of 1941, the Battle of the Atlantic was going in Germany’s favour. There was, in other words, some reason for Germans to believe that an armistice might be possible ~ freeing up all of Germany’s power to be used against the USSR.)

(But things were changing for the Allies, too. At just about the same time as Hess was flying to Scotland, then Commodore Leonard Murray of the Royal Canadian Navy, who had been in England on other duties, had met with and persuaded Admiral Sir Percy Noble, who liked Murray and had been his commander in earlier years, that a new convoy escort force should be established in Newfoundland and that it should be a largely Canadian force (with British, Dutch, Norwegian and Polish ships under command, too) and that it should be commanded by a Canadian officer. Admiral Noble insisted, to Canada, that Murray, who he liked, personally, and who had written, extensively, on convoy operations in the 1920s and ’30s, must be that commander. The establishment of the Newfoundland Escort Force, which would be more appropriately renamed the Mid Ocean Escort Force in 1942, was a key decision at the much-debated operational level of war which put an expert tactician (Murray) in command of a major force and allowed him (and Noble) to move closer to achieving Churchill’s strategic aim. The Battle of the Atlantic was not won in 1941, but it seemed to Churchill, Noble and Murray that they were a lot less likely to lose it, even without the Americans.)

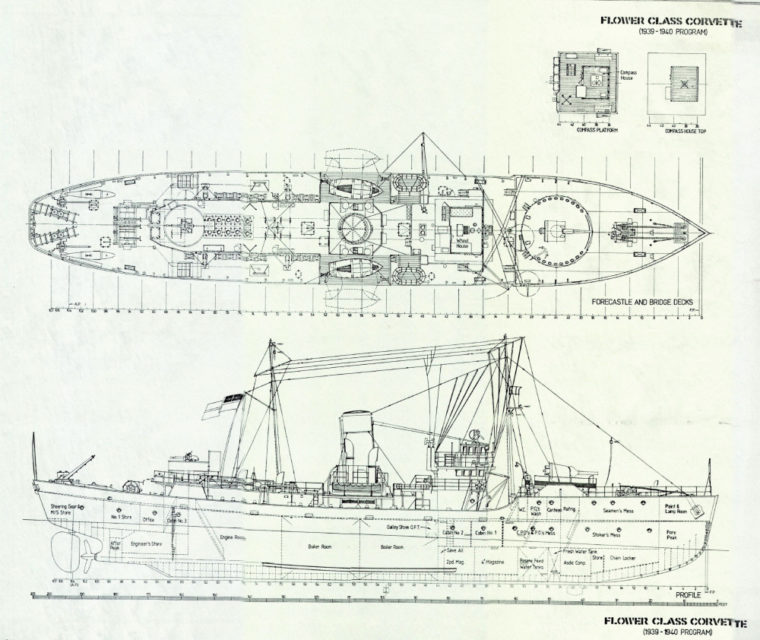

Diagram of the early Flower-class corvettes, via Lt. Mike Dunbar (https://visualfix.wordpress.com/2017/04/12/dreadful-wale-4/)

Anyway, the boundaries of strategy vs. the operational art vs. tactics were as thick and blurry in 1941 as they are today. The decision, taken in 1939, for example, to build little corvettes in the many British and Canadian yards that could not build a real warship was, in retrospect, a key strategic choice, but it was, at the time, totally materialist: just a commonsense, engineer solution to an operational problem ~ lack of ships. Ditto for the eventual decision, which had to be made by Churchill, himself, to reassign some of the big, long-range, Lancaster heavy bombers to Coastal Command. It was, once again, with the benefit of hindsight, a key strategic move, but at the time it would likely have seemed, to Capt(N) Hugues Canuel, the author of that Canadian Naval Review essay, to be materialistic, more concerned with how to use the resources available than with deciding what is needed.

I agree with Capt(N) Canuel that, by and large, Canadians have left strategic and even operational level thinking to first, the British and more recently the American admirals ~ Rear Admiral Murray being known, in the 1930s and early 1940s as a notable exception.

March 22, 2020

Culling the Nazi Wolfpacks – Submarines, Spies, China, and Africa – WW2 – 082 – March 21 1941

World War Two

Published 21 Mar 2020While two more Kriegsmarine U-boat aces go down, the moving parts of the war are getting more complex leaving the intelligence services scrambling to separate fact from fiction — they don’t always get it right.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Or join The TimeGhost Army directly at: https://timeghost.tvFollow WW2 day by day on Instagram @World_war_two_realtime https://www.instagram.com/world_war_t…

Between 2 Wars: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list…

Source list: http://bit.ly/WW2sourcesWritten and Hosted by: Indy Neidell

Produced and Directed by: Spartacus Olsson and Astrid Deinhard

Executive Producers: Bodo Rittenauer, Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson

Creative Producer: Joram Appel

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: Indy Neidell

Edited by: Iryna Dulka

Map animations: Eastory (https://www.youtube.com/c/eastory)Colorizations by:

– Olga Shirnina a.k.a. Klimbim – https://klimbim2014.wordpress.com/

– Dememorabilia – https://www.instagram.com/dememorabilia/

– Julius Jääskeläinen – https://www.facebook.com/JJcolorization/Sources:

– BundesarchivArchive by Screenocean/Reuters https://www.screenocean.com.

A TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

From the comments:

World War Two

2 days ago

Indy is at the studio in Bavaria at the moment, shooting new episodes up to May 2020. We don’t know what impact the virus has on our production beyond that, but for now we seem to be fine. That is, thanks to your support! Most of our other (personal) sources of income has fallen away now – we are not able to pay everyone a fair wage just yet. In fact, most of the budget goes into licensing, equipment, editors, researchers and travel. If you can, please consider to support us on www.patreon.com/timeghosthistory or https://timeghost.tv so we can continue to make these series! Thank you all for your support and appreciation! Take care and be safe!

Cheers, Joram

March 8, 2020

Bulgaria Joins the Fascist Alliance – WW2 – 080 – March 7, 1941

World War Two

Published 7 March 2020German troops pour into Bulgaria as they join the Axis alliance, while British troops enter Greece in anticipation of a German attack. Meanwhile, the British celebrate victories in East-Africa and on the Atlantic.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Or join The TimeGhost Army directly at: https://timeghost.tvFollow WW2 day by day on Instagram @World_war_two_realtime https://www.instagram.com/world_war_t…

Between 2 Wars: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list…

Source list: http://bit.ly/WW2sourcesWritten and Hosted by: Indy Neidell

Produced and Directed by: Spartacus Olsson and Astrid Deinhard

Executive Producers: Bodo Rittenauer, Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson

Creative Producer: Joram Appel

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: Indy Neidell

Edited by: Iryna Dulka

Map animations: Eastory (https://www.youtube.com/c/eastory)Colorizations by:

– Royal Bulgaria In Colour

– Daniel Weiss

– Dememorabilia – https://www.instagram.com/dememorabilia/

– Julius Jääskeläinen – https://www.facebook.com/JJcolorization/

– Norman Stewart – https://oldtimesincolor.blogspot.com/Sources:

– Bundesarchiv

– Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe

– IWM: TR 1762, CM 187, MH 27178, E 2370, E 2380, K 284, E 2376, E 1384, E 2383, E 3245, E 2001, E 2393

– Moscow icon by Graphic Tigers, film icon by Fernando Vasconcelos, oil barrel icon by Musmellow, from the Noun Project

– Slide projector sound by hpebley3 from Freesound.orgArchive by Screenocean/Reuters https://www.screenocean.com.

A TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

February 16, 2020

Enter Erwin Rommel – The British Advance in Africa – WW2 – 077 – February 15 1941

World War Two

Published 15 Feb 2020While the Germans send one of their best generals to North Africa to bail out the Italians, Great Britain switches focus from Libya to Greece, but make symbolically important gains in East Africa.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Or join The TimeGhost Army directly at: https://timeghost.tvFollow WW2 day by day on Instagram @World_war_two_realtime https://www.instagram.com/world_war_t…

Join our Discord Server: https://discord.gg/D6D2aYN

Between 2 Wars: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list…

Source list: http://bit.ly/WW2sourcesWritten and Hosted by: Indy Neidell

Produced and Directed by: Spartacus Olsson and Astrid Deinhard

Executive Producers: Bodo Rittenauer, Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson

Creative Producer: Joram Appel

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: Indy Neidell

Edited by: Iryna Dulka

Map animations: Eastory (https://www.youtube.com/c/eastory)Colorizations by:

– Julius Jääskeläinen – https://www.facebook.com/JJcolorization/

– Norman Stewart – https://oldtimesincolor.blogspot.com/Sources:

– Bundesarchiv

– A German soldier poses atop a tank, photo credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Perquimans County Library

– US National Archive

– IWM: A 4035, HU 39482Archive by Screenocean/Reuters https://www.screenocean.com.

A TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

From the comments:

World War Two

2 days ago

When you know the story going forward it’s fascinating to see how the decisions unfold this week — the reshuffling of command both on the Axis and Allied side might seem like innocuous administrative decisions when you don’t know the future. But if you have a crystal ball, you’ll know that not just Rommel arriving in North Africa, but also the decisions on the British side this week will have momentous impact on the war in total. That’s one of the things we discovered early-on with a chronological narrative, it suddenly puts things in a new perspective. The relationship between events changes, and things that might seem too boring, or undramatic to include in a “great story” take on a whole new meaning, increasing our understanding of cause and effect of the “greater” events that will come. On a different note, we just finished shooting a new batch of videos today and we’ll be announcing some fascinating developments on our program in the coming weeks. Stay tuned, and stay awesome, you all are by far the best community on YouTube!

February 14, 2020

“Wolfpack” – German U-boat Tactics – Sabaton History 054 [Official]

Sabaton History

Published 13 Feb 2020The Battle of Britain had saved the United Kingdom from imminent invasion by the German Wehrmacht, however the war was far from over. To destroy Britain’s economic capabilities to wage war, the German Kriegsmarine had to win the tonnage war in the North Atlantic. The German submarines — the U-Boote, were sent out to hunt. As the British Royal Navy returned to the convoy system to protect its merchant fleet, the Germans as well began organizing their submarines in groups to attack in unison. These hunter-killer teams, the Wolfpacks, would soon haunt the depths of the North Atlantic.

Support Sabaton History on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/sabatonhistory

Listen to “Wolfpack” on the album Primo Victoria:

CD: http://bit.ly/PrimoVictoriaStore

Spotify: http://bit.ly/PrimoVictoriaSpotify

Apple Music: http://bit.ly/PrimoVictoriaAppleMusic

iTunes: http://bit.ly/PrimoVictoriaiTunes

Amazon: http://bit.ly/PrimoVictoriaAmzn

Google Play: http://bit.ly/PrimoVictoriaGooglePlayCheck out the trailer for Sabaton’s new album The Great War right here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HCZP1…

Listen to Sabaton on Spotify: http://smarturl.it/SabatonSpotify

Official Sabaton Merchandise Shop: http://bit.ly/SabatonOfficialShopHosted by: Indy Neidell

Written by: Markus Linke and Indy Neidell

Directed by: Astrid Deinhard and Wieke Kapteijns

Produced by: Pär Sundström, Astrid Deinhard and Spartacus Olsson

Creative Producer: Joram Appel

Executive Producers: Pär Sundström, Joakim Broden, Tomas Sunmo, Indy Neidell, Astrid Deinhard, and Spartacus Olsson

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Edited by: Iryna Dulka

Sound Editing by: Marek Kaminski

Maps by: Eastory – https://www.youtube.com/c/eastoryArchive by: Reuters/Screenocean https://www.screenocean.com

Music by Sabaton.Colorizations:

– Olga Shirnina, a.k.a. Klimbim – https://klimbim2014.wordpress.com/Sources:

– IWM: HU 16546, A 30292

– Bundesarchiv

– Otis Historical Archives, National Museum of Health and Medicine

– Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe

– Canadian ship being attacked, photo courtesy of the Government of Canada, https://www.canada.ca/en/navy/service…An OnLion Entertainment GmbH and Raging Beaver Publishing AB co-Production.

© Raging Beaver Publishing AB, 2019 – all rights reserved.

November 10, 2019

Britain’s First Victory, Germany Plunders Europe & Mussolini’s Folly – WW2 – 063 – November 9, 1940

World War Two

Published 9 Nov 2019The Battle of Britain is finished, but the war is far from over. New German plans are being made for the Balkans and Greece, where the Italian offensive is not as successful as planned.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Or join The TimeGhost Army directly at: https://timeghost.tvFollow WW2 day by day on Instagram @World_war_two_realtime https://www.instagram.com/world_war_t…

Join our Discord Server: https://discord.gg/D6D2aYN.

Between 2 Wars: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list…

Source list: http://bit.ly/WW2sourcesWritten and Hosted by: Indy Neidell

Produced and Directed by: Spartacus Olsson and Astrid Deinhard

Executive Producers: Bodo Rittenauer, Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson

Creative Producer: Joram Appel

Research by: Indy Neidell

Edited by: Iryna Dulka

Map animations: EastoryColorizations: Julius Jääskeläinen https://www.facebook.com/JJcolorization/

Thumbnail Colorization: Julius JääskeläinenEastory’s channel: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCEly…

Archive by Screenocean/Reuters https://www.screenocean.com.Sources:

– Money and factory icons by Adrien Coquet, ship icon by Edward Boatman, all: from the Noun Project

– IWM: HU 1915, ZZZ 1811C, IND 3595, E 1227, E 1107, E 1242, E 1239

– San Demetrio crew by Arranj on Wikimedia Commons

– Narodowe Archiwum CyfroweA TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

From the comments:

World War Two

2 days ago (edited)

Now that the new Greek offensive has been launched a week ago, more troops are moving and more terrain is changing hands. We are very lucky to have Eastory make maps for our episodes, allowing us to visualize movements and geographicial locations. Furthermore, Eastory is a historian who is very skilled in researching the exact locations and movements of fighting units. For these episodes, he has had some help from our loyal community member Avalantis. This really shows how much this channel is a team effort and how important our community is to us and our videos. If you want to contribute as well, you can start with supporting us on https://www.patreon.com/timeghosthistory or https://timeghost.tv. Every dollar counts!

Cheers, the TimeGhost team

October 20, 2019

USA enters WW2 in 1940?! – WW2 – 060 – October 19, 1940

World War Two

Published 19 Oct 2019The World War seems to get bigger and bigger as Italy plans to invade Greece and the USA takes a stance.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Or join The TimeGhost Army directly at: https://timeghost.tvFollow WW2 day by day on Instagram @World_war_two_realtime https://www.instagram.com/world_war_t…

Join our Discord Server: https://discord.gg/D6D2aYN.

Between 2 Wars: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list…

Source list: http://bit.ly/WW2sourcesWritten and Hosted by: Indy Neidell

Produced and Directed by: Spartacus Olsson and Astrid Deinhard

Executive Producers: Bodo Rittenauer, Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson

Creative Producer: Joram Appel

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: Indy Neidell

Edited by: Iryna Dulka

Map animations: EastoryColorisations by Norman Stewart and Julius Jääskeläinen https://www.facebook.com/JJcolorization/

Eastory’s channel: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCEly…

Archive by Screenocean/Reuters https://www.screenocean.com.A TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

September 22, 2019

The Brits teach the Germans to bugger off! – WW2 – 056 – September 21 1940

World War Two

Published on 21 Sep 2019The Battle of Britain continues as planes fight over the South-English shorelines and large parts of London are targeted during the Blitz. However, this week the ultimate goal of this air battle is postponed. The invasion of Britain, Operation Sea Lion, is called off. For now at least.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Or join The TimeGhost Army directly at: https://timeghost.tvFollow WW2 day by day on Instagram @World_war_two_realtime https://www.instagram.com/world_war_t…

Join our Discord Server: https://discord.gg/D6D2aYN.

Between 2 Wars: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list…

Source list: http://bit.ly/WW2sourcesWritten and Hosted by: Indy Neidell

Produced and Directed by: Spartacus Olsson and Astrid Deinhard

Executive Producers: Bodo Rittenauer, Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson

Creative Producer: Joram Appel

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: Indy Neidell

Edited by: Iryna Dulka

Map animations: EastoryColorisations by Norman Stewart and Julius Jääskeläinen https://www.facebook.com/JJcolorization/

Eastory’s channel: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCEly…

Archive by Screenocean/Reuters https://www.screenocean.com.Sources:

– Mussolini colorized by Olga Shirnina, aka Klimbim

– German barge by WerWil on Wikimedia Commons

– IWM: CM3513, MH 6657, ZZZ 2070B, MISC 51237A TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.