Tom Scott

Published 17 Oct 2022At the Swiss Military Museum in Full, there’s the last remaining example of a 1970s tank-driving simulator. But there’s no virtual worlds here: it’s connected to a real camera and a real miniature model. ■ More about the museum: https://www.festungsmuseum.ch/

(more…)

February 5, 2023

This 1970s tank simulator drives through a tiny world

QotD: Annual cycles of plenty and scarcity in pre-modern agricultural societies

This brings us to the most fundamental fact of rural life in the pre-modern world: the grain is harvested once a year, but the family eats every day. Of course that means the grain must be stored and only slowly consumed over the entire year (with some left over to be used as seed-grain in the following planting). That creates the first cycle in agricultural life: after the harvest, food is generally plentiful and prices for it are low […] As the year goes on, food becomes scarcer and the prices for it rise as each family “eats down” their stockpile.

That has more than just economic impacts because the family unit becomes more vulnerable as that food stockpile dwindles. Malnutrition brings on a host of other threats: elevated risk of death from injury or disease most notably. Repeated malnutrition also has devastating long-term effects on young children […] Consequently, we see seasonal mortality patterns in agricultural communities which tend to follow harvest cycles; when the harvest is poor, the family starts to run low on food before the next harvest, which leads to rationing the remaining food, which leads to malnutrition. That malnutrition is not evenly distributed though: the working age adults need to be strong enough to bring in the next harvest when it comes (or to be doing additional non-farming labor to supplement the family), so the short rations are going to go to the children and the elderly. Which in turn means that “lean” years are marked by increased mortality especially among the children and the elderly, the former of which is how the rural population “regulates” to its food production in the absence of modern birth control (but, as an aside: this doesn’t lead to pure Malthusian dynamics – a lot more influences the food production ceiling than just available land. You can have low-equilibrium or high-equilibrium systems, especially when looking at the availability of certain sorts of farming capital or access to trade at distance. I cannot stress this enough: Malthus was wrong; yes, interestingly, usefully wrong – but still wrong. The big plagues sometimes pointed to as evidence of Malthusian crises have as much if not more to do with rising trade interconnectedness than declining nutritional standards). This creates yearly cycles of plenty and vulnerability […]

Next to that little cycle, we also have a “big” cycle of generations. The ratio of labor-to-food-requirements varies as generations are born, age and die; it isn’t constant. The family is at its peak labor effectiveness at the point when the youngest generation is physically mature but hasn’t yet begun having children (the exact age-range there is going to vary by nuptial patterns, see below) and at its most vulnerable when the youngest generation is immature. By way of example, let’s imagine a family (I’m going to use Roman names because they make gender very clear, but this is a completely made-up family): we have Gaius (M, 45), his wife, Cornelia (39, F), his mother Tullia (64, F) and their children Gaius (21, M), Secundus (19, M), Julia1 (16, F) and Julia2 (14, F). That family has three male laborers, three female laborers (Tullia being in her twilight years, we don’t count), all effectively adults in that sense, against 7 mouths to feed. But let’s fast-forward fifteen years. Gaius is now 60 and slowing down, Cornelia is 54; Tullia, we may assume has passed. But Gaius now 36 is married to Clodia (20, F; welcome to Roman marriage patterns), with two children Gaius (3, M) and Julia3 (1, F); Julia1 and Julia2 are married and now in different households and Secundus, recognizing that the family’s financial situation is never going to allow him to marry and set up a household has left for the Big City. So we now have the labor of two women and a man-and-a-half (since Gaius the Elder is quite old) against six mouths and the situation is likely to get worse in the following years as Gaius-the-Younger and Clodia have more children and Gaius-the-Elder gets older. The point of all of this is to note that just as risk and vulnerability peak and subside on a yearly basis in cycles, they also do this on a generational basis in cycles.

(An aside: the exact structure of these generational patterns follow on marriage patterns which differ somewhat culture to culture. In just about every subsistence farming culture I’ve seen, women marry young (by modern standards) often in their mid-to-late teens, or early twenties; that doesn’t vary much (marriage ages tend to be younger, paradoxically, for wealthier people in these societies, by the by). But marriage-ages for men vary quite a lot, from societies where men’s age at first marriage is in the early 20s to societies like Roman and Greece where it is in the late 20s to mid-thirties. At Rome during the Republic, the expectation seems to have been that a Roman man would complete the bulk of their military service – in their twenties and possibly early thirties – before starting a household; something with implications for Roman household vulnerability. Check out Rosenstein, op. cit. on this).

On top of these cycles of vulnerability, you have truly unpredictable risk. Crops can fail in so many ways. In areas without irrigated rivers, a dry spell at the wrong time is enough; for places with rivers, flooding becomes a concern because the fields have to be set close to the water-table. Pests and crop blights are also a potential risk factor, as of course is conflict.

So instead of imagining a farm with a “standard” yield, imagine a farm with a standard grain consumption. Most years, the farm’s production (bolstered by other activities like sharecropping that we’ll talk about later) exceed that consumption, with the remainder being surplus available for sale, trade or as gifts to neighbors and friends. Some years, the farm’s production falls short, creating that shortfall. Meanwhile families tend to grow to the size the farm can support, rather than to the labor needs the farm has, which tends to mean too many hands (and mouths) and not enough land. Which in turn causes the family to ride a line of fairly high risk in many cases.

All of this is to stress that these farmers are looking to manage risk through cycles of vulnerability […]

I led in with all of that risk and vulnerability because without it just about nothing these farmers do makes a lot of sense; once you understand that they are managing risk, everything falls into place.

Most modern folks think in terms of profit maximization; we take for granted that we will still be alive tomorrow and instead ask how we can maximize how much money we have then (this is, admittedly, a lot less true for the least fortunate among us). We thus tend to favor efficient systems, even if they are vulnerable. From this perspective, ancient farmers – as we’ll see – look very silly, but this is a trap, albeit one that even some very august ancient scholars have fallen into. These are not irrational, unthinking people; they are poor, not stupid – those are not the same things.

But because these households wobble on the edge of disaster continually, that changes the calculus. These small subsistence farmers generally seek to minimize risk, rather than maximize profits. After all, improving yields by 5% doesn’t mean much if everyone starves to death in the third year because of a tail-risk that wasn’t mitigated. Moreover, for most of these farmers, working harder and farming more generally doesn’t offer a route out of the small farming class – these societies typically lack that kind of mobility (and also generally lack the massive wealth-creation potential of industrial power which powers that kind of mobility). Consequently, there is little gain to taking risks and much to lose. So as we’ll see, these farmers generally sacrifice efficiency for greater margins of safety, every time.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Bread, How Did They Make It? Part I: Farmers!”, A collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-07-24.

February 4, 2023

Federal regulation of the Canadian book market has resulted in 95% of the market now being foreign owned

For the record, I don’t think this kind of cultural regulation is a good idea to start with, but as Ken Whyte points out, if staving off foreign ownership was the primary intent, could it have failed any more comprehensively than this?

Sometime last year, the Association of Canadian Publishers, which represents most of the independent book publishers in English Canada (Sutherland House is not a member), began discussing a radical — some might say dangerous — new form of regulation for the Canadian book industry.

The ACP started from the reasonable position that the existing federal approach to regulating the Canadian book industry has failed. That approach is to encourage a Canadian-owned book sector and, ipso facto, to discourage foreign ownership of Canadian publishing. Successive Canadian governments, Conservative and Liberal, have paid lip-service to the policy and failed to enforce it. The multinational publishers — Simon & Schuster, Penguin Random House, HarperCollins — have moved into Canada in a big way. Great chunks of the Canadian-owned industry, including McClelland & Stewart and Harlequin Books, have been sold to foreign buyers.

The multinationals now account for about 95 or 96 percent of book sales in Canada. All but the last 5 or 6 percent of their revenue comes from sales of imported books, most of them produced in the US or UK.

The Canadian-owned component of the book sector, which produces the vast majority of Canadian author books, has shrunk to about 4 or 5 percent of the market and sales of Canadian-authored books, says the ACP, have “flatlined”.

So you can see why the ACP is interested in a new approach: for more than half a century, while pursuing an official policy of encouraging Canadian-ownership, our government has managed to hand almost the whole of our book industry to foreign-owned firms.

I, too, am interested in a new approach. It’s the ACP’s next step that worries me.

The ACP has been watching over the past couple of years as the federal government rewrites its Broadcasting Act. The thrust of Bill C-11 is to bring foreign-owned streaming services operating in Canada — the likes of Netflix, Apple, YouTube — under the jurisdiction of the Canadian Radio-televison and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC). The bill would grant the CRTC the power to impose on streaming services the same rules it imposes on the likes of CTV and Global and the companies that own them. It would compel streamers to use Canadian talent, abide by Canadian diversity requirements, prioritize Canadian content on their platforms, and give a percentage of their revenues to a fund to support the production of Canadian content.

It has occurred to the ACP that no one in government is asking foreign-owned book publishers to abide by Canadian content quotas or to deliver percentages of their revenue to a fund to support Canadian-owned book producers: “The absence of a CRTC or related regulatory body, along with the policies and programs that such a body can enact, has meant that non-Canadian firms enjoy unfettered access to the Canadian marketplace.”

That’s not quite right. Non-Canadian firms dominate Canadian publishing because the feds won’t enforce their existing policy, not because we don’t have a CRTC for books. In any event, the ACP is embracing the spirit of Bill C-11.

Oh, goody! Government bureaucratic oversight is bound to make Canadians more interested in reading Canadian books, right? I see no way that this could possibly fail.

Poland’s Descent into Civil War – War Against Humanity 097

World War Two

Published 2 Feb 2023Poland, occupied, abandoned or even threatened by her allies is left to fight her own war. A war that under the influence of internal and external forces looks more and more like a full blown civil war inside the world war.

(more…)

A lobster tale (that does not involve Jordan Peterson)

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes relates some of his recent research on the Parliament of 1621 (promising much more in future newsletters) and highlights one of the Royal monopolies that came under challenge in the life of that Parliament:

One of the great things about the 1621 Parliament, as a historian of invention, is that MPs summoned dozens of patentees before them, to examine whether their patents were “grievances” — illegal and oppressive monopolies that ought to be declared void. Because of these proceedings, along with the back-and-forth of debate between patentees and their enemies, we can learn some fascinating details about particular industries.

Like how 1610s London had a supply of fresh lobsters. The patent in question was acquired in 1616 by one Paul Bassano, who had learned of a Dutch method of keeping lobsters fresh — essentially, to use a custom-made broad-bottomed ship containing a well of seawater, in which the lobsters could be kept alive. Bassano, in his petitions to the House of Commons, made it very clear that he was not the original inventor and had imported the technique. This was exactly the sort of thing that early monopoly patents were supposed to encourage: technological transfer, and not just original invention.

The problem was that the patent didn’t just cover the use of the new technique. It gave Bassano and his partners a monopoly over all imported lobsters too. This was grounded in a kind of industrial policy, whereby blocking the Dutch-caught lobsters would allow Bassano to compete. He noted that Dutch sailors were much hardier and needed fewer provisions than the English, and that capital was available there at interest rates of just 4-5%, so that a return on sales of just 10% allowed for a healthy profit. In England, by comparison, interest rates of about 10% meant that he needed a return on sales of at least 15%, especially given the occasional loss of ships and goods to the capriciousness of the sea — he noted that he had already lost two ships to the rocks.

At the same time, patent monopolies were designed to nurture expertise. Bassano noted that he still needed to rely on the Dutch, who were forced to sell to the English market either through him or by working on his ships. But he had been paying his English sailors higher wages, so that over time the trade would come to be dominated by the English. (This training element was a key reason that most patents tended to be given for 14 or 21 years — the duration of two or three apprenticeships — though Bassano’s was somewhat unusual in that it was to last for a whopping 31.)

But the blocking of competing imports — especially foodstuffs, which were necessaries of life — could be very controversial, especially when done by patent rather than parliamentary statute. Monopolies could lawfully only be given for entirely new industries, as they otherwise infringed on people’s pre-existing practices and trades. Bassano had worked out a way to avoid complaints, however, which was essentially to make a deal with the fishmongers who had previously imported lobsters, taking them into his partnership. He offered them a win-win, which they readily accepted. In fact, the 1616 patent came with the explicit support of the Fishmongers’ Company.

It sounds like it became a large enterprise, and I suspect that it probably did lower the price of lobsters in London, bringing them in regularly and fresh. With a fleet of twenty ships, and otherwise supplementing their catch with those caught by the Dutch, Bassano boasted of how he was able to send a fully laden ship to the city every day (wind-permitting). This stood in stark contrast to the state of things before, when a Dutch ship might have arrived with a fresh catch only every few weeks or months, and when they felt that scarcity would have driven the prices high.

“Ghost Riders In The Sky”

Audio Saurus

Published 30 Oct 2015Neil LeVang in 1961 on The Lawrence Welk Show.

QotD: Leftists against humanity

Yesterday in a group, a friend said what is obvious about the left is that they seriously oppose human reproduction and longevity. Ultimately human life, I guess.

Here’s the list as to why:

NOT AN EXHAUSTIVE LIST:

1) Pushing to maximize abortion

2) Pushing to maximize homosexuality

3) Multiple different initiatives to make child rearing more difficult and expensive including

a) Ramping up the intensity of social services scrutiny, effectively necessitating high intensity “helicopter parenting”

b) Turning schools into indoctrination factories that don’t prepare children to function independently but do prepare them to have constant fights with their parents over their indoctrination

c) Making healthcare more expensive through constantly ramping regulation, making the actual having of children more difficult and prohibitively expensive

d) Pushing to nationalize healthcare, granting them further power over who lives or dies – allowing limitation of IVF, and also

e) legitimizing legal euthanasia while also pushing to make healthcare decisions for the public (see Canada right now)4) Pushing from other regulatory angles to make the de facto standard a two-income family, ensuring children are raised in daycares and further pushing family budgets to the brink

5) Using the student loan system to turn the bulk of reproductive age, upwardly mobile people into collateral in a deal that passes billions of dollars directly from the US government to the same system that then indoctrinates those kids to the point of full societal dysfunction; encouraging, as much as possible, the use of sex as entertainment ONLY

6) Turning sterilizing yourself into the hot new fad for kids

7) Turning the simple identification of gender into a minefield so that even sex between people who aren’t mutilating themselves is suddenly difficult to even consider

8) Willfully manipulating nursing homes into putting elderly people in a position where they are MOST LIKELY to die during COVID

9) Adopting COVID policies which foreseeably shut down cancer diagnostics and treatment for almost two years, which is the most likely cause of the 10 fold increase in the rate of cancers since the COVID lockdowns (although I can’t entirely discount that the vaccines themselves are partially responsible because, sing it with me now, you can’t ensure the long term safety of something that hasn’t been around long enough to have long term safety data, which is why we do clinical trials and not mass experiments on the general public. I note in passing that the drug companies are so trustworthy they demanded legal indemnity as a condition of participating, while swearing blind that the product was safe and effective even though it was physically fucking impossible for them to have data to back that up due to minor problems like the requisite quantity of time not passing.)

Sarah Hoyt, “I Don’t Believe in Aliens”, According to Hoyt, 2022-10-31.

February 3, 2023

“Lady of The Dark” – Milunka Savić – Sabaton History 117

Sabaton History

Published 2 Feb 2023One of the most badass and decorated soldiers of the Great War was a woman. Serving first in the Balkan Wars, this Serbian war heroin became a celebrity when she won the Karađorđe’s Star — the highest Serbian decoration — in 1914 and 1916. Those weren’t her only decorations either — watch to find out more.

(more…)

Tank Chats #166 | SOMUA S35 | The Tank Museum

The Tank Museum

Published 14 Oct 2022Join David Willey in this week’s Tank Chat as he details the history of the SOMUA S35, a French cavalry tank of the Second World War.

(more…)

QotD: Democracy

They’re all, Democrats and Republicans alike, playing Washington Bingo, which is the Glass Bead Game for retards — nobody really knows what it is or why anyone bothers, but it keeps them occupied in nice cushy offices, with weekends in the Hamptons.

Democracy always devolves into ochlocracy, as some Dead White Male said, but since the last Dead White Male died centuries before Twitter, he didn’t realize that ochlocracy was just a pit stop on the way to kakistocracy.

“Democracy” only works — if, in fact, it does work, which is a very fucking open question — in a stakeholder society. When Madison and the boys pledged their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor to each other, they meant all of that literally — Washington could well have died a pauper, Alexander Hamilton ordered his cannon to fire on his own house, and so on. They had skin in the game, which is why they were so public-spirited — if they screwed up, they personally would have to live with the consequences. These days, of course, getting “elected” — or even selected to run for “election” — is a free pass to Easy Street. The rules apply only to the plebs, and only so long — and, insh’allah, the day is soon coming — as we have to pretend to let them “vote” on stuff.

Severian, “The Stakeholder State”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-01-22.

February 2, 2023

Stop FAILING in your woodwork. Use these strategies instead.

Rex Krueger

Published 1 Feb 2023Simple steps lead to great progress, the same is true in your woodworking.

(more…)

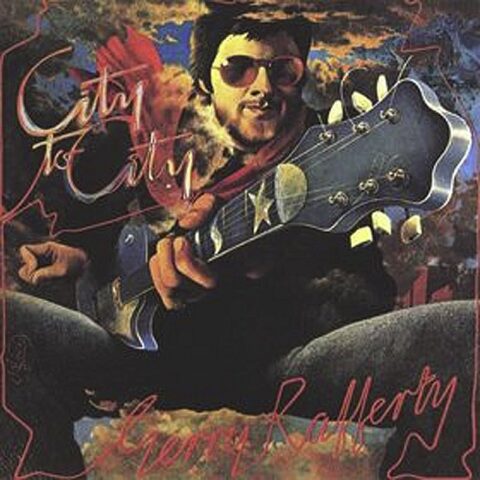

Gerry Rafferty’s “Baker Street” lyrics

When I first subscribed to Ted Gioia’s Honest Broker substack, I figured I’d find one or two posts a month that I found interesting enough to share on the blog … I have to be careful not to link to several of his posts every week. He writes a lot about the music industry, so when this popped up in my inbox, I assumed it was Ted and got to the point of scheduling it before I realized it was Jon Miltimore instead:

I was recently in a bar having dinner with a friend when Gerry Rafferty’s hit 1978 song “Baker Street” came on. When my friend mentioned that he loved the song, I agreed and noted the song’s powerful lyrics.

“Really?” he responded. “I never paid much attention to the lyrics.”

Most people, of course, remember “Baker Street” for its wailing saxophone, and my friend was no different. Nor was I, for many years. But at some point—I don’t know when—I began to pay attention to the song’s lyrics. They go like this:

Winding your way down on Baker Street

Light in your head and dead on your feet

Well, another crazy day

You’ll drink the night away

And forget about everythingThis city desert makes you feel so cold

It’s got so many people, but it’s got no soul

And it’s taken you so long

To find out you were wrong

When you thought it held everythingYou used to think that it was so easy

You used to say that it was so easy

But you’re trying, you’re trying now

Another year and then you’d be happy

Just one more year and then you’d be happy

But you’re crying, you’re crying nowWay down the street there’s a light in his place

He opens the door, he’s got that look on his face

And he asks you where you’ve been

You tell him who you’ve seen

And you talk about anythingHe’s got this dream about buying some land

He’s gonna give up the booze and the one-night stands

And then he’ll settle down

In some quiet little town

And forget about everythingBut you know he’ll always keep moving

You know he’s never gonna stop moving

‘Cause he’s rolling, he’s the rolling stone

And when you wake up, it’s a new morning

The sun is shining, it’s a new morning

And you’re going, you’re going homeThe lyrics — in contrast to the seductive sax and upbeat strings and keyboard — are rather dark. It’s not your typical rock/pop song about finding or losing love.

I’ve never heard “Baker Street” explained, but my take on the song is this: It’s about two lonely people in a city. They find comfort in booze, chemicals, and (occasionally) each other. The relationship is probably dysfunctional, but they are struggling to change. Struggling to grow. Struggling to find meaning.

“Baker Street” peaked at #3 in the UK and held the #2 spot in the U.S. for six consecutive weeks. I think part of the reason the song was such a success is because the lyrics touched on something a little deeper than most rock tunes, something that resonated with audiences. And though the song is 40 years old now, I have a hunch it resonates even more now than it did then.

MAC Model 1947 Prototype SMGs

Forgotten Weapons

Published 12 Oct 2022Immediately upon the liberation of France in 1944, the French military began a process of developing a whole new suite of small arms. As it applied to SMGs, the desire was for a design in 9mm Parabellum (no more 7.65mm French Long), with an emphasis on something light, handy, and foldable. All three of the French state arsenals (MAC, MAS, and MAT) developed designs to meet the requirement, and today we are looking at the first pair of offerings from Chatellerault (MAC). These are the 1947 pattern, a very light lever-delayed system with (frankly) terrible ergonomics.

Many thanks to the French IRCGN (Criminal Research Institute of the National Gendarmerie) for generously giving me access to film these unique specimens for you!

Today’s video — and many others — have been made possible in part by my friend Shéhérazade (Shazzi) Samimi-Hoflack. She is a real estate agent in Paris who specializes in working with English-speakers, and she has helped me arrange places to stay while I’m filming in France. I know that exchange rates make this a good time for Americans to invest in Europe, and if you are interested in Parisian real estate I would highly recommend her. She can be reached at: samimiconsulting@gmail.com

(Note: she did not pay for this endorsement)

(more…)