John H. Cochrane on the benefits and harms that aid from rich countries has done to the poor recipient nations around the world:

At half the dinners I go to, someone says, well, yes, a lot of the USAID money was mis-spent, but what about the poor starving children in Africa? If you are in that situation, this is the article for you.

This article is about about the centerpiece of aid: “development” aid, designed to boost economic growth, not about the politicized “nonprofits” that USAID was supporting and their bloated staffs, funneling aid money to political advocacy and employment, promoting American self-loathing around the world, and so forth.

Development spending accounts for almost three-quarters of all aid.

And the enterprise is a colossal failure.

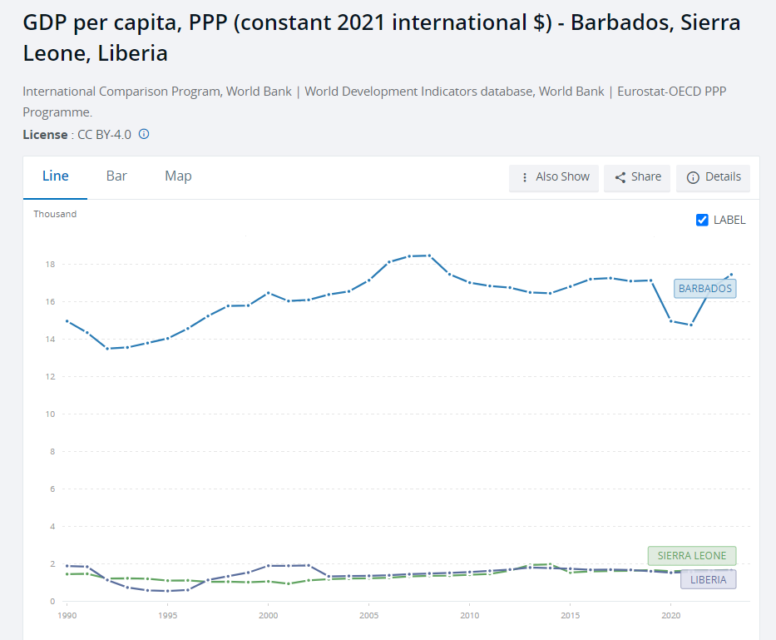

The capital of Malawi, one of the world’s poorest countries, runs on aid. A city built in the 1970s by the World Bank, Lilongwe’s straight streets are filled with charities, development agencies and government offices. Informal villages house cooks and cleaners for foreign officials; the entrance to each is marked with the flag of its national sponsor.

The money is small compared to advanced country GDP, but huge compared to poor country government resources […]

The results of such spending are no better in Malawi than in the US — even if it’s free to the recipient. Add the preference of aid advocates for “sustainable” or “appropriate” and “green” technology, including these days hostility to GMO foods, and social or environmental wrappers, “climate justice” and so on, indeed even the hostility to capitalism, “consumerism” and growth itself and it’s not a surprise this is a rathole. (Again, it’s cheap from our perspective. The problem is that it’s wholly ineffective. If money really could jump start growth, that would be great.)

One of the central conundrums of aid is that it can destroy local industry. Sending food, for example, seems like a no-brainer of mercy. And in a war, crop failure, or other catastrophe it is. But sending food on a regular basis bankrupts local farmers.

Central idea 1: Imagine just how happy the US might be if China decided in its mercy to tax Chinese citizens, buy crops at overvalued prices (which incidentally pleases Chinese farmers), and send bags of rice to the US for free, marked “gift of the CCP”, thereby bankrupting US rice farmers. Or if it decided to send us really cheap electric vehicles to help us speed towards net zero, thereby undermining our own state-supported EV business. Well, you know exactly how our government feels about this sort of thing! And this is exactly what aid does.

Now, a good free market economist welcomes subsidized imports, and a push to leave agriculture and move to export-oriented manufacturing or other higher value industries. But Malawi doesn’t have other higher value industries, and exporting anything to the advanced economies is getting harder and harder. Extending the old proverb, send a man a fish a day forever, and he forgets how to fish.

The article opened my eyes (some more) to the delicate intertwining of economics and politics. We really don’t live in a free market world in the US (note our executives rushing to change ideology and please the new team in Washington), and even less so in poor countries.

Western aid officials often want to prevent local politicians, who control crucial industries, from profiting as a result of their projects, meaning they select obscure sectors for tax breaks, credit and subsidies. With few investors willing to stump up capital, and little interest from local politicians, the businesses duly flop.

Here is a conundrum for you. Without 10% off the top for the big guy, businesses will flounder.