The Line‘s weekly dispatch is, as usual, mostly behind the paywall but the portion visible to cheapskates contains much of interest:

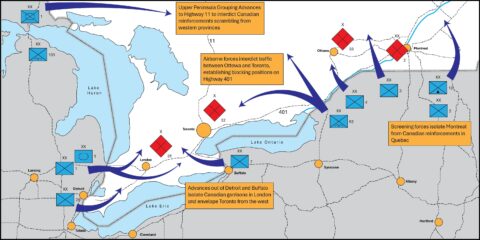

Manifest Destiny, 2025? Big Serge’s updated map for the old US War Plan Red for a military invasion of Canada.

It’s no coincidence that as Canada’s leadership devolved into its own navel, the very-soon-to-be-inaugurated Donald Trump escalated his provocations. This week, Trump threatened to use “economic force” to push Canada to bend the knee. Meanwhile, we cannot help but notice that the idea of a Canadian state is starting to gain significant traction in even moderate and mainstream American conservative circles. Meanwhile, we’ve got Alberta Premier Danielle Smith supping with Kevin O’Leary and Jordan Peterson down in Mar-a-Lago.

Tap tap. May we suggest that you peruse the safety cards tucked into the back of your seat, buckle up, and take note of your nearest emergency exits?

Whether we are talking about some kind of economic union, or a full-blown annexation, the fact that at least some in America are reviving the term “Manifest Destiny” is a possibility that we can no longer afford to dismiss as mere trolling. While we hope that the Trump administration is going to be so bogged down with other policy priorities that “Canada 51” is soon overshadowed, your Line editors have been game theorying out a host of possible scenarios and … none of them look great. If Trump et al get serious about this idea — and, again, we have no way to know if they will get serious about this idea — then we at The Line fear that Canada is in for some serious turmoil in the coming few months.

As I said in an email to Severian the other week, “… Canada will have very little ability to react to whatever Hitler, er, I mean “Trump” will do as soon as he’s inaugurated. It was clear before this that Trudeau cared very little about ordinary Canadians’ lives, but this really is dereliction of duty on a cosmic scale. If Trump does follow through with that huge tariff, the Canadian economy is likely to collapse, as we’re so deeply intertwined with the US on so many levels. Sadly, this might make it even more attractive to Trump, as it would absolutely encourager les autres on a global scale. If the BOM is willing to destroy the economy of his closest trading partner, what might he do to France? Or Germany? Or South Korea?” Back to the dispatch:

To explain our alarm, let’s first look at another news item to cross the desk. This week, Justin Trudeau travelled south to attend the funeral of Jimmy Carter, and stopped at the CNN studios for a quick interview with Jake Tapper on the way through.

On the whole, we think his interview was fine. Look, Trudeau’s been through a lot in the last few days, and considering the circumstances, it’s not reasonable to expect a breakthrough performance. So we’re being a bit unkind to nitpick, but something he said during that interview deserves scrutiny.

Justin Trudeau got far too comfortable with being treated as a progressive superstar, not only among the sycophants with CBC nametags but even on the international stage … perhaps especially on the international stage. Trudeau was always inclined to the performative in everything he did, and he might well only feel fully alive when cameras are rolling. The evidence certainly seems to point in that direction.

The “most prolific Canadian actor” meme was mildly amusing during Trudeau’s first term in office, as he went out of his way to put on elaborate costumes and to perform for the audience. This sort of thing was understandable if not particularly welcome to those who wanted Canada to be taken seriously by our allies and trading partners. It was clichéd to joke about what novelty socks Trudeau was wearing at any given international event … because it was his trademark. As was the clearly diminished respect he got as his time in office went on.

When asked about Trump’s provocations, Trudeau affirmed Canadians’ pride in their own sovereignty by noting — half jokingly, we presume — that we fundamentally define ourselves as “not American”.

Firstly, this is not a particularly diplomatic jibe to be launched at actual ordinary Americans; it made us wince to consider how it must have landed to CNN’s ordinary watching audience.

Secondly, if the only way in which Canadians can define themselves nowadays is “not-American”, Jeez, that’s an extraordinarily thin peg upon which to hang a hat.

This stuff matters.

It is to wince. However, even that pathetic response was better than launching into yet another diatribe about Trudeau’s firm conviction that Canadians are all genocidal white supremacist morons, I guess.

The ability of a population to withstand neighbourly aggression — “economic force”, if you will — depends on two things. The first is internal social cohesion and identity. The second is what the aggressor is willing to do or offer in order to secure capitulation.

In this case, the second part of that equation is outside our control. So we look to the first: does Canada have a strong sense of self right now? Do its leaders command the moral authority necessary to create the social cohesion required to withstand a period of sustained material sacrifice?

If we are “not Americans”, it rather asks the question why aren’t we Americans? And, more crucially, what are we actually willing to give up in order to preserve that independence?

A people can be rallied to make extraordinary sacrifices for a greater ideal, including the ideal of independent nationhood. Look at the sacrifices of blood and treasure made every day in Ukraine, for example.

If necessary, Canadians can band together and survive on lentils and supply managed dairy and eggs for many months or years. We can pull together through a period of inconceivable material hardship — but only if we’re doing it for something. Canadians, as per usual, can talk a big game, but how many of us are willing to suffer a real collapse of our quality of life to preserve a quasi-ironic, tautological, or negative self-identity?

Before Trudeau’s time in office, I wouldn’t have thought to question Canadians’ pride in their country and willingness to defend it. Nearly ten years later, Trudeau and his minions have done a fantastic job of undermining any kind of patriotic enthusiasms in our “post-national state”, haven’t they?

We at The Line don’t believe there is even a vanishingly small chance of the Americans using martial force to secure Canada — and if they choose to amass a brigade at the border on Monday morning, we’re all taking the Pledge of Allegiance by noon, so let’s not grace this fantasy with a lot of real consideration.

I’d love to refute that, but it’s probably true, at least in the more densely populated areas of southern Canada … the US could send a brigade north to Vancouver, another to Calgary, another to Winnipeg, and one to Montreal. Thanks to the lower lakes, it’d take a bit more to secure Toronto and Ottawa but not a lot more. We literally couldn’t stop them, both because our very limited troops are not positioned to stop an invasion from the south and because they’re not even close to being in a ready-to-move condition. Even our local reserves would have to be notified, travel to their local armouries, be issued weapons and the very limited amount of ammunition kept in local storage and by the time they were ready, there’s a foreign flag waving over Queen’s Park and Parliament hill.

Big Serge’s map at the top of this post vastly overstates the number of US troops necessary to secure the major population areas.

However, it is worthwhile to imagine it as a pure thought experiment: what would you really be willing to give up in order to continue to be “not-American”.

Your investment savings? Your property? Your house? Would you sacrifice the life of your child, or your grandchild, to preserve the legal independence of Canada?

We ask this question not because we think it’s going to come to that, but rather because these questions test the integrity of our national concept. They allow us to examine our resilience, and our willingness to withstand an assault of an economic or moral nature. And, folks, we’re just not convinced that our national resilience is very high at the moment.

Well, I’m sure a lot of new Canadians would want the rest of us to defend the place while they take advantage of all the government and corporate positions that need to be “diversified” … surely us evil white supremacists are willing to lay it all on the line for a more diverse society, right?

It was interesting to us to note, this week, that the most powerful moral appeal for the concept of nationhood was proposed in a Globe and Mail oped by Jean Chrétien. While we salute the old patriot, we can’t help but point out that he’s, well, very old — 91, to be precise.

We at The Line have a sneaking suspicion that Canadian patriotism and, more importantly, a willingness to make serious sacrifices to preserve that patriotism, is going to decline precipitously by age cohort in any well-constructed survey of the topic.

Would the young fight to preserve Canada against the Russians or the Chinese? Yes, we think our fellow Canadians could absolutely be called upon to make serious sacrifices to circumvent the rule of autocrats and dictators. But to prevent being subsumed by the — checks notes — wealthiest and most powerful democratic nation on earth (presuming America stays that way)? A nation that shares almost all of our essential values; one that looks and sounds just like us, and would probably provide a better set of opportunities to our kids? The place an increasing number of us are going to do start business and receive timely medical care?

Why?

Why would we do that? Can someone — anyone — please articulate a vision, here? Is anyone in our leadership class even trying?

It’s been noted many times that people are willing to charge even bare-handed into machine guns and cannons for things like “Liberté, égalité, fraternité“, but nobody is going to man the ramparts for “peace and good government”.

We put a lot of the blame for this on Justin Trudeau, and on the identitarian politics that consciously sought to undermine national legitimacy in the pursuit of progressive ends. But, if we’re being honest, we think this complacency of identity predates these social movements by many decades.

The Liberal Party as an institution owns a lot of it for the ways in which the “Natural Governing Party” has tied national identity to its preferred partisan policy options, at the direct expense of more transcendental and bi-partisan national self concepts. The Liberals have usurped “Canada” into a party brand

The national flag is effectively the Liberal Party flag … thanks Mr. Pearson!

and marshalled the very concept of “patriotism” to build consensus for picayune material entitlements. Trudeau couldn’t even help but do this in his CNN interview with Jake Tapper this week: “We delivered $10-a-day childcare. We’re delivering a dental care program that provides free dental care for people who don’t have coverage. We’re moving forward on a price on pollution that puts more money in the pockets of eight out 10 Canadians.”

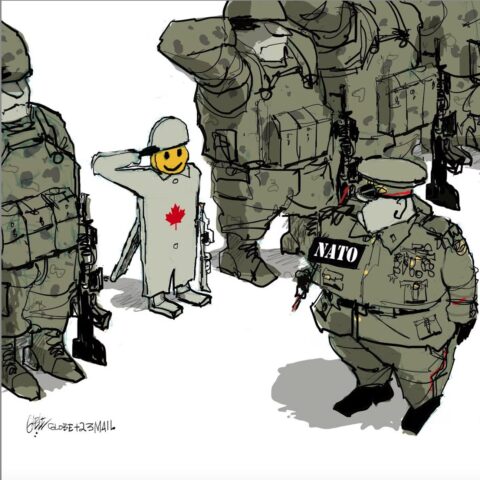

We suppose Trudeau found that argument very compelling argument to Americans marvelling at Canada’s inability to meet its basic NATO commitments.

The weird thing is that Trudeau could have deflected a lot of these criticisms by our NATO allies almost painlessly without spending any more money directly on the Canadian Armed Forces — “It’s well known that Justin Trudeau has no time for military issues, but it’s surprising that he hasn’t done a few things that wouldn’t increase the actual spending on the CAF, but would be “bookkeeping” changes that would shift some existing government spending into the military category, like militarizing the Canadian Coast Guard. (That is, moving the CCG from the Fisheries and Oceans portfolio into the National Defence portfolio, not actually putting armaments on CCG vessels. Something similar could be done with the RCMP, switching it from Public Safety to National Defence with no other funding or operational changes.) That Trudeau hasn’t chosen to make even these symbolic changes shows that he actively opposes fulfilling the commitment his government has made twice in the last ten years for reasons of his own.”

This tactic has been very electorally effective for the Liberals, no doubt, but it’s also reduced the idea of “Canada” to a smug transactional exchange. “Canada” as nothing more than what provinces and citizens can wheedle out of the commonweal in transfer payments, equalization cheques, and grandiose but poorly executed national program spending. At least we’re better than America, though, right? We’re “not American!” — we’re so much more thoughtful and compassionate, as evidenced by the entitlements we’ve voted for ourselves, secure in the knowledge that the troglodytes to the south will spend and bleed and die for our coddled asses if Russia lobs a missile from the North.

Canada has become a question of what we, citizens, are able to get, rather than one of what we’re willing to give. And we’re smarmy, preachy assholes about it, to boot. (There’s a very famous political quote we could drop in here about what citizens can do for their countries and vice versa, but you’ll know why we aren’t, if you can guess the quote! It would be a little on the nose.)

A nation that is unwilling to make serious sacrifices of blood and treasure to protect its own sovereignty is a nation that is going to cease to be a nation sooner or later — and if we judge Canada by its commitment to its military, ours is a nation that has regarded itself as a quasi-ironic post-modern punchline for many generations now.