In the latest SHuSH newsletter, Kenneth Whyte explains some of the issues publishers face in getting their books printed, as most publishers outsourced the actual physical work of printing and binding many years back:

I had a serious conversation with another publisher this week about the need for publishers to start printing their own books.

Those familiar with publishing history will know that from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century, most publishers printed their own books. Ownership of a press, as much as anything, was what made a publisher a publisher. In the course of the twentieth century, it was decided that publishing books and printing books were different businesses. Virtually all publishers outsourced their printing to high-volume printing specialists who were constantly upgrading their equipment, and who, theoretically, at least, were better, faster, and cheaper than in-house printing operations.

[…]

Apart from that handful of artisans, today’s book publisher can no more operate a printing press than a backhoe. He or she outsources printing to specialists on a project-by-project basis.

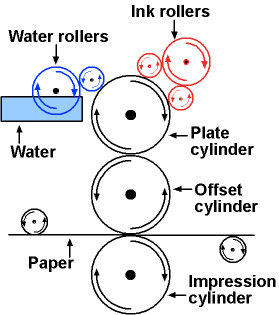

The options for large-scale quality printing are increasingly scarce, thanks to a lot of consolidation in the printing business. Smaller shops (like the artisans) only do paperbacks; hardcovers require a lot of expensive binding equipment. If a publisher wants a big run of a hardcover title, the most likely printers are the industry giants: R.R. Donnelley (above) or CJK Group in the US; Friesens and Marquis in Canada. These companies all use huge offset web presses that are big as gymnasiums and only economically efficient at higher quantities (i.e., in the thousands). The technology involves metal plates and rubber mats and massive rolls of paper (if you’re interested, read more here) and the quality is first rate.

I should have said that the only options for a big run of hardcovers in Canada are Friesens in Altona, Manitoba and Marquis in Montmagny, Quebec. There are no hardcover printing options in Ontario, where so many publishers are concentrated (although Marquis does have a plant in Toronto).

[…]

The reason publishers are now talking about doing their own printing is that it is increasingly difficult to get time on any kind of press. Friesens, when Sutherland House started a few years ago, could usually do a job for us in eight weeks. There were seasons — the dead of winter, the height of summer — when they could deliver even faster and we’d get a discount because their presses weren’t especially busy. COVID-19 changed all that.

People have been buying more books during the pandemic, and publishers have been printing more. Friesens is now fully booked six to eight months out; its fall 2022 schedule is already crowded. The US printers we use as alternatives to Friesens are similarly backed up.

It’s making the decision to print in hardcover hazardous. It used to be that if you printed a few thousand copies of a new book in hardcover and it was in danger of selling out, you could get back on press in six to eight weeks, maybe less, and continue to fill orders. Now, if that original press run is selling fast, you might have to wait six to eight months to print a second edition. You’ll be out-of-print for most of that time, and all momentum will be lost. Some publishers are thus moving immediately to digital paperback formats (none of the digital printers have hardcover binderies) for their second editions, even if it’s only weeks into a book’s life. There is more availability at digital printers, so resorting to the digital paperback format allows you to keep your momentum.