Sumer just before the dawn of civilization was in many ways an idyllic place. Forget your vision of stark Middle Eastern deserts; in the Paleolithic the area where the first cities would one day arise was a great swamp. Foragers roamed the landscape, eating everything from fishes to gazelles to shellfish to wild plants. There was more than enough for everyone; “as Jack Harlan famously showed, one could gather enough [wild] grain with a flint sickle in three weeks to feed a family for a year”. Foragers alternated short periods of frenetic activity (eg catching as many gazelles as possible during their weeklong migration through the area) with longer periods of rest and recreation.

Intensive cereal cultivation is miserable work requiring constant toil with little guarantee of a good harvest. Why would anyone leave this wilderness Eden for a 100% wheat diet?

Not because they were tired of wandering around; Scott presents evidence that permanent settlements began as early as 6000 BC, long before Uruk, the first true city-state, began in 3300. Sometimes these towns subsisted off of particularly rich local wildlife; other times they practiced some transitional form of agriculture, which also antedated states by millennia. Settled peoples would eat whatever plants they liked, then scatter the seeds in particularly promising-looking soil close to camp – reaping the benefits of agriculture without the back-breaking work.

And not because they needed to store food. Hunter-gatherers could store food just fine, from salting animal meat to burying fish and letting it ferment to just having grain in siloes like everyone else. There is ample archaeological evidence of all of these techniques. Also, when you are surrounded by so much bounty, storing things takes on secondary importance.

And not because the new lifestyle made this happy life even happier. While hunter-gatherers enjoyed a stable and varied diet, agriculturalists subsisted almost entirely on grain; their bones display signs of significant nutritional deficiency. While hunter-gatherers were well-fed, agriculturalists were famished; their skeletons were several inches shorter than contemporaneous foragers. While hunter-gatherers worked ten to twenty hour weeks, agriculturalists lived lives of backbreaking labor. While hunter-gatherers who survived childhood usually lived to old age, agriculturalists suffered from disease, warfare, and conscription into dangerous forced labor.

Scott Alexander, “Book Review: Against The Grain“, Slate Star Codex, 2019-10-15.

April 15, 2024

QotD: Cereal cultivation also helped grow the centralized state

November 20, 2023

QotD: Flax and linen in the ancient and medieval world

Linen fabrics are produced from the fibers of the flax plant, Linum usitatissimum. This common flax plant is the domesticated version of the wild Linum bienne, domesticated in the northern part of the fertile crescent no later than 7,000 BC, although wild flax fibers were being used to produce textiles even earlier than that. Consequently the use of linen fibers goes way back. In fact, the oldest known textiles are made from flax, including finds of fibers at Nahal Hemar (7th millennium BC), Çayönü (c. 7000 BC), and Çatalhöyük (c. 6000 BC). Evidence for the cultivation of flax goes back even further, with linseed from Tell Asward in Syria dating to the 8th millennium BC. Flax was being cultivated in Central Europe no later than the second half of the 7th millennium BC.

Flax is a productive little plant that produces two main products: flax seeds, which are used to produce linseed oil, and the bast of the flax plant which is used to make linen. The latter is our focus here so I am not going to go into linseed oil’s uses, but it should be noted that there is an alternative product. That said, my impression is that flax grown for its seeds is generally grown differently (spaced out, rather than packed together) and generally different varieties are used. That said, flax cultivated for one purpose might produce some of the other product (Pliny notes this, NH 19.16-17)

Flax was a cultivated plant (which is to say, it was farmed); fortunately we have discussed quite a bit about farming in general already and so we can really focus in on the peculiarities of the flax plant itself; if you are interested in the activities and social status of farmers, well, we have a post for that. Flax farming by and large seems to have involved mostly the same sorts of farmers as cereal farming; I get no sense in the Greco-Roman agronomists, for instance, that this was done by different folks. Flax farming changed relatively little prior to mechanization; my impression reading on it is that flax was farmed and gathered much the same in 1900 BC as it was in 1900 AD. In terms of soil, flax requires quite a lot of moisture and so grows best in either deep loam or (more commonly used in the ancient world, it seems) alluvial soils; in both cases, it should be loose, unconsolidated “sandy” (that is, small particle-sized) soil. Alluvium is loose, often sandy soil that is the product of erosion (that is to say, it is soil composed of the bits that have been eroded off of larger rocks by the action of water); the most common place to see lots of alluvial soil are in the flood-plains of rivers where it is deposited as the river floods forming what is called an alluvial plain.

Thus Pliny (NH 19.7ff) when listing the best flax-growing regions names places like Tarragona, Spain (with the seasonally flooding Francoli river) or the Po River Basin in Italy (with its large alluvial plain) and of course Egypt (with the regular flooding of the Nile). Pliny notes that linen from Sætabis in Spain was the best in Europe, followed by linens produced in the Po River Valley, though it seems clear that the rider here “made in Europe” in his text is meant to exclude Egypt, which would have otherwise dominated the list – Pliny openly admits that Egyptian flax, while making the least durable kind of linen (see below on harvesting times) was the most valuable (though he also treats Egyptian cotton which, by his time, was being cultivated in limited amounts in the Nile delta, as a form of flax, which obviously it isn’t). Flax is fairly resistant to short bursts of mild freezing temperatures, but prolonged freezes will kill the plants; it seems little accident that most flax production seems to have happened in fairly warm or at least temperate climes.

Flax is (as Pliny notes) a very fast growing plant – indeed, the fastest growing crop he knew of. Modern flax grown for fibers is generally ready for harvesting in roughly 100 days and this accords broadly with what the ancient agronomists suggest; Pliny says that flax is sown in spring and harvested in summer, while the other agronomists, likely reflecting practice further south suggest sowing in late fall and early winter and likewise harvesting relatively quickly. Flax that is going to be harvested for fibers tended to be planted in dense bunches or rows (Columella notes this method but does not endorse it, De Rust. 2.10.17). The reason for this is that when placed close together, the plants compete for sunlight by growing taller and thinner and with fewer flowers, which maximizes the amount of stalk per plant. By contrast, flax planted for linseed oil is more spaced out to maximize the number of flowers (and thus the amount of seed) per plant.

Once the flax was considered ready for harvest, it was pulled up out of the ground (including the root system) in bunches in handfuls rather than as individual plants […] and then hung to dry. Both Pliny and Columella (De Rust. 2.10.17) note that this pulling method tended to tear up the soil and regarded this as very damaging; they are on to something, since none of the flax plant is left to be plowed under, flax cultivation does seem to be fairly tough on the soil (for this reason Columella advises only growing flax in regions with ideal soil for it and where it brings a good profit). The exact time of harvest varies based on the use intended for the flax fibers; harvesting the flax later results in stronger, but rougher, fibers. Late-pulled flax is called “yellow” flax (for the same reason that blond hair is called “flaxen” – it’s yellow!) and was used for more work-a-day fabrics and ropes.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Clothing, How Did They Make It? Part I: High Fiber”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-03-05.

November 8, 2023

Sampling the alternate history field

Jane Psmith confesses a weakness for a certain kind of speculative fiction and recommends some works in that field. The three here are also among my favourites, so I can comfortably agree with the choices:

As I’ve written before, I am an absolute sucker for alternate history. Unfortunately, though, most of it is not very good, even by the standards of genre fiction’s transparent prose. Its attraction is really the idea, with all its surprising facets, and means the best examples are typically the ones where the idea is so good — the unexpected ramifications so startling at the moment but so obvious in retrospect — that you can forgive the cardboard characters and lackluster prose.

But, what the heck, I’m feeling self-indulgent, so here are some of my favorites.

- Island in the Sea of Time et seq., by S.M. Stirling: This is my very favorite. The premise is quite simple: the island of Nantucket is inexplicably sent back in time to 1250 BC. Luckily, a Coast Guard sailing ship happens to be visiting, so they’re able to sail to Britain and trade for grain to survive the winter while they bootstrap industrial civilization on the thinly-inhabited coast of North America. Of course, it’s not that simple: the inhabitants of the Bronze Age have obvious and remarkably plausible reactions to the sudden appearance of strangers with superior technology, a renegade sailor steals one of the Nantucketers’ ships and sets off to carve his own empire from the past, and the Americans are thrust into Bronze Age geopolitics as they attempt to thwart him. The “good guys” are frankly pretty boring, in a late 90s multicultural neoliberal kind of way — the captain of the Coast Guard ship is a black lesbian and you can practically see Stirling clapping himself on the back for Representation — but the villainous Coast Guardsmen and (especially) the natives of 1250 BC get a far more complex and interesting portrayal.1 Two of them are particularly well-drawn: a fictional trader of the thinly attested Iberian city-state of Tartessos, and an Achaean nobleman named Odikweos, both of whom are thoroughly understandable and sympathetic while remaining distinctly unmodern. The Nantucketers, with their technological innovations and American values, provide plenty of contrast, but Stirling is really at his best in using them to highlight the alien past.

- Lest Darkness Fall, by L. Sprague de Camp: An absolute classic of the genre. I may not love what de Camp did with Conan, but the man could write! One of the great things about old books (this one is from 1939) is that they don’t waste time on technobabble to justify the silly parts: about two pages into the story, American archaeologist Martin Padway is struck by lightning while visiting Rome and transported back in time to 535 AD. How? Shut up, that’s how, and instead pay attention as Padway introduces distilled liquor, double-entry bookkeeping, yellow journalism, and the telegraph before taking advantage of his encyclopedic knowledge of Procopius’s De Bello Gothico to stabilize and defend the Italo-Gothic kingdom, wrest Belisarius’s loyalty away from Justinian, and entirely forestall the Dark Ages. If this sounds an awful lot like the imaginary book I described in my review of The Knowledge: yes. The combination of high agency history rerouting and total worldview disconnect — there’s a very funny barfight about Christology early on, and later some severe culture clash that interferes with a royal marriage — is charming. Also, this was the book that inspired Harry Turtledove not only to become an alt-history writer but to get a Ph.D. in Byzantine history.

[…]

- Ruled Britannia, by Harry Turtledove: Turtledove is by far the most famous and successful alternate history author out there, with lots of short pieces and novels ranging from “Byzantine intrigue in a world where Islam never existed” (Agent of Byzantium) to “time-travelling neo-Nazis bring AK-47s to the Confederacy” (The Guns of the South), but this is the only one of his books I’ve ever been tempted to re-read. The jumping-off point, “the Spanish Armada succeeded”, is fairly common for the genre2 — the pretty good Times Without Number and the lousy Pavane (hey, did you know the Church hates and fears technology?!) both start from there — but Turtledove fasts forward only a decade to show us William Shakespeare at the fulcrum of history. A loyalist faction (starring real life Elizabethan intriguers like Nicholas Skeres) wants him to write a play about Boudicca to inflame the population to free Queen Elizabeth from her imprisonment in the Tower of London, while the Spanish authorities (represented, hilariously, by playwright manqué Lope de Vega) want him to write one glorifying the late Philip II and the conquest of England. Turtledove does a surprisingly good job inventing new Shakespeare plays from snippets of real ones and from John Fletcher’s 1613 Bonduca, but of course I’m most taken by his rendition of the Tudor world. Maybe I should check out some of his straight historical fiction …

1. Well, except for the peaceful matriarchal Marija Gimbutas-y “Earth People” being displaced from Britain by the invading Proto-Celts; they’re also “good guys” and therefore, sadly, boring.

2. Not as common as “the Nazis won”, obviously.

I agree with Jane about Island in the Sea of Time, but my son and daughter-in-law strongly preferred the other series Stirling wrote from the same start point: what happened to the world left behind when Nantucket Island got scooped out of our timeline and dumped back into the pre-collapse Bronze Age. Whereas ISOT has minimal supernatural elements to the story, the “Emberverse” series beginning with Dies the Fire went on for many, many more books and had much more witchy woo-woo stuff front-and-centre rather than marginal and de-emphasized.

While I quite enjoyed Ruled Britannia, it was the first Turtledove series I encountered that I’ve gone back to re-read: The Lost Legion … well, the first four books, anyway. He wrote several more books in that same world, but having wrapped up the storyline for the Legion’s main characters, I didn’t find the others as interesting.

October 14, 2023

QotD: Horses and sheep on the Eurasian Steppe

Now just because this subsistence system is built around the horse doesn’t mean it is entirely made up by horses. Even once domesticated, horses aren’t very efficient animals to raise for food. They take too long to gestate (almost a year) and too long to come to maturity (technically a horse can breed at 18 months, but savvy breeders generally avoid breeding horses under three years – and the Mongols were savvy horse breeders). The next most important animal, by far is the sheep. Sheep are one of the oldest domesticated animals (c. 10,000 BC!) and sheep-herding was practiced on the steppe even before the domestication of the horse. Steppe nomads will herd other animals – goats, yaks, cattle – but the core of the subsistence system is focused on these two animals: horses and sheep. Sheep provide all sorts of useful advantages. Like horses, they survive entirely off of the only resource the steppe has in abundance: grass. Sheep gestate for just five months and reach sexual maturity in just six months, which means a small herd of sheep can turn into a large herd of sheep fairly fast (important if you are intending to eat some of them!). Sheep produce meat, wool and (in the case of females) milk, the latter of which can be preserved by being made into cheese or yogurt (but not qumis, as it will curdle, unlike mare’s milk). They also provide lots of dung, which is useful as a heating fuel in the treeless steppe. Essentially, sheep provide a complete survival package for the herder and conveniently, made be herded on foot with low manpower demands.

Now it is worth noting right now that Steppe Nomads have, in essence, two conjoined subsistence systems: there is one system for when they are with their herds and another for purely military movements. Not only the sheep, but also the carts (which are used to move the yurt – the Mongols would call it a ger – the portable structure they live in) can’t move nearly as fast as a Steppe warrior on horseback can. So for swift operational movements – raids, campaigns and so on – the warriors would range out from their camps (and I mean range – often we’re talking about hundreds of miles) to strike a target, leaving the non-warriors (which is to say, women, children and the elderly) back at the camp handling the sheep. For strategic movements, as I understand it, the camps and sheep herds might function as a sort of mobile logistics base that the warriors could operate from. We’ll talk about that in just a moment.

So what is the nomadic diet like? Surely it’s all raw horse-meat straight off of the bone, right? Obviously, no. The biggest part of the diet is dairy products. Mare’s and sheep’s milk could be drunk as milk; mare’s milk (but not sheep’s milk) could also be fermented into what the Mongolians call airag but is more commonly known as qumis after its Turkish name (note that while I am mostly using the Mongols as my source model for this, Turkic Steppe nomads are functioning in pretty much all of the same ways, often merely with different words for what are substantially the same things). But it could also be made into cheese and yogurt [update: Wayne Lee (@MilHist_Lee) notes that mare’s milk cannot be made into yogurt, so the yogurt here would be made from sheep’s milk – further stressing the importance of sheep!] which kept better, or even dried into a powdered form called qurut which could then be remixed with water and boiled to be drunk when it was needed […] The availability of fresh dairy products was seasonal in much of the steppe; winter snows would make the grass scarce and reduce the food intake of the animals, which in turn reduced their milk production. Thus the value of creating preserved, longer-lasting products.

Of course they did also eat meat, particularly in winter when the dairy products became scarce. Mutton (sheep meat) is by far largest contributor here, but if a horse or oxen or any other animal died or was too old or weak for use, it would be butchered (my understanding is that these days, there is a lot more cattle in Mongolia, but the sources strongly indicate that mutton was the standard Mongolian meat of the pre-modern period). Fresh meat was generally made into soup called shulen (often with millet that might be obtained by trade or raiding with sedentary peoples or even grown on some parts of the steppe) not eaten raw off of the bone. One of our sources, William of Rubruck, observed how a single sheep might feed 50-100 men in the form of mutton soup. Excess meat was dried or made into sausages. On the move, meat could be placed between the rider’s saddle and the horse’s back – the frequent compression of riding, combined with the salinity of the horse’s sweat would produce a dried, salted jerky that would keep for a very long time.

(This “saddle jerky” seems to gross out my students every time we discuss the Steppe logistics system, which amuses me greatly.)

Now, to be clear, Steppe peoples absolutely would eat horse meat, make certain things out of horsehair, and tan horse hides. But horses were also valuable, militarily useful and slow to breed. For reasons we’ll get into a moment, each adult male, if he wanted to be of any use, needed several (at least five). Steppe nomads who found themselves without horses (and other herds, but the horses are crucial for defending the non-horse herds) was likely to get pushed into the marginal forest land to the north of the steppe. While the way of life for the “forest people” had its benefits, it is hard not to notice that forest dwellers who, through military success, gained horses and herds struck out as steppe nomads, while steppe nomads who lost their horses became forest dwellers by last resort (Ratchnevsky, op. cit., 5-7). Evidently, being stuck as one of the “forest people” was less than ideal. In short, horses were valuable, they were the necessary gateway into steppe life and also a scarce resource not to be squandered. All of which is to say, while the Mongols and other Steppe peoples ate horse, they weren’t raising horses for the slaughter, but mostly eating horses that were too old, or were superfluous stallions, or had become injured or lame. It is fairly clear that there were never quite enough good horses to go around.

Bret Devereaux, “That Dothraki Horde, Part II: Subsistence on the Hoof”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-12-11.

September 21, 2023

QotD: The Iliad as Bronze Age gangsta rap

A few months ago I tried moving the Iliad from the list of books I’m good at pretending to have read to the list of books I’ve actually read, and to my surprise I bounced off of it pretty hard. What I wasn’t expecting was how much of it is just endlessly tallied lists of gruesome slayings, disses, shoutouts to supporters, more killings, women taken by force, boasts about wealth, boasts about blinged-out-equipment, more shoutouts to the homies from Achaea who here repreSENTing, etc. The Iliad is basically one giant gangster rap track, and gangster rap is kinda boring.

What was cool though is I felt like I came away with a much better understanding of Socrates, Plato, and that whole milieu. Much like it’s easy to miss the radicalism of Christianity when you come from a culture steeped in it, it’s easy to miss the radicalism of Socrates if you don’t understand that this is the culture he was reacting against. Granted, the compilation of the Homeric epics took place centuries before the time of classical Athens, but my sense is that in important respects things hadn’t changed all that much. In our society, even people who aren’t professing Christians have been subliminally shaped by a vast set of Christian-inflected moral and epistemic and metaphysical assumptions. Well in the same way, in the Athens of Socrates and of the Academy, the “cultural dark matter” was the world of the Iliad: honor, glory, blinged out bronze armor, tearing hot teenagers from the arms of their lamenting parents, etc.

We have a tendency to think of the Greek philosophers as emblematic of their civilization, when in reality they were one of the most bizarre and unrepresentative things that happened in that society. But Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges is here to tell us it wasn’t just the philosophers! So much of our mental picture of Ancient Greece and Rome is actually a snapshot of one fleeting moment in the histories of those places, arguably a very unrepresentative moment at which everything was in the process of collapsing. It’s like if [POP CULTURE ANALOGY I’M TOO TIRED TO THINK OF]. And actually once you think about it this way, everything makes way more sense. All those weird customs the Greeks and Romans had, all the lares and penates and herms and stuff, those are what these societies were about for hundreds and hundreds of years, and the popular image is just this weird encrustation, this final flowering at the end.

Jane and John Psmith, “JOINT REVIEW: The Ancient City, by Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-02-20.

September 8, 2023

QotD: Rents and taxes in pre-modern societies

In most ways […] we can treat rent and taxes together because their economic impacts are actually pretty similar: they force the farmer to farm more in order to supply some of his production to people who are not the farming household.

There are two major ways this can work: in kind and in coin and they have rather different implications. The oldest – and in pre-modern societies, by far the most common – form of rent/tax extraction is extraction in kind, where the farmer pays their rents and taxes with agricultural products directly. Since grain (threshed and winnowed) is a compact, relatively transportable commodity (that is, one sack of grain is as good as the next, in theory), it is ideal for these sorts of transactions, although perusing medieval manorial contacts shows a bewildering array of payments in all sorts of agricultural goods. In some cases, payment in kind might also come in the form of labor, typically called corvée labor, either on public works or even just farming on lands owned by the state.

The advantage of extraction in kind is that it is simple and the initial overhead is low. The state or large landholders can use the agricultural goods they bring in in rents and taxes to directly sustain specialists: soldiers, craftsmen, servants, and so on. Of course the problem is that this system makes the state (or the large landholder) responsible for moving, storing and cataloging all of those agricultural goods. We get some sense of how much of a burden this can be from the prominence of what seem to be records of these sorts of transactions in the surviving writing from the Bronze Age Near East (although I should note that many archaeologists working on the ancient Near Eastern economy are pushing for a somewhat larger, if not very large, space for market interactions outside of the “temple economy” model which has dominated the field for quite some time). This creates a “catch” we’ll get back to: taxation in kind is easy to set up and easier to maintain when infrastructure and administration is poor, but in the long term it involves heavier administrative burdens and makes it harder to move tax revenues over long distances.

Taxation in coin offers potentially greater efficiency, but requires more particular conditions to set up and maintain. First, of course, you have to have coinage. That is not a given! Much of the social interactions and mechanics of farming I’ve presented here stayed fairly constant (but consult your local primary sources for variations!) from the beginnings of written historical records (c. 3,400 BC in Mesopotamia; varies place to place) down to at least the second agricultural revolution (c. 1700 AD in Europe; later elsewhere) if not the industrial revolution (c. 1800 AD). But money (here meaning coinage) only appears in Anatolia in the seventh century BC (and probably independently invented in China in the fourth century BC). Prior to that, we see that big transactions, like long-distance trade in luxuries, might be done with standard weights of bullion, but that was hardly practical for a farmer to be paying their taxes in.

Coinage actually takes even longer to really influence these systems. The first place coinage gets used is where bullion was used – as exchange for big long-distance trade transactions. Indeed, coinage seemed to have started essentially as pre-measured bullion – “here is a hunk of silver, stamped by the king to affirm that it is exactly one shekel of weight”. Which is why, by the by, so many “money words” (pounds, talents, shekels, drachmae, etc.) are actually units of weight. But if you want to collect taxes in money, you need the small farmers to have money. Which means you need markets for them to sell their grain for money and then those merchants need to be able to sell that grain themselves for money, which means you need urban bread-eaters who are buying bread with money, which means those urban workers need to be paid in money. And you can only get any of these people to use money if they can exchange that money for things they want, which creates a nasty first-mover problem.

We refer to that entire process as monetization – when I talk about economies being “monetized” or “incompletely monetized” that’s what I mean: how completely has the use of money penetrated through this society. It isn’t a one-way street, either. Early and High Imperial Rome seem to have been more completely monetized than the Late Roman Western Empire or the early Middle Ages (though monetization increases rapidly in the later Middle Ages).

Extraction, paradoxically, can solve the first mover problem in monetization, by making the state the first mover. If the state insists on raising taxes in money, it forces the farmers to sell their grain for money to pay the tax-man; the state can then take that money and use it to pay soldiers (almost always the largest budget-item in an ancient or medieval state budget), who then use the money to buy the grain the farmers sold to the merchants, creating that self-sustaining feedback loop which steadily monetizes the society. For instance, Alexander the Great’s armies – who expected to be paid in coin – seem to have played a major role in monetizing many of the areas they marched through (along with breaking things and killing people; the image of Alexander the Great’s conquests in popular imagination tend to be a lot more sanitized).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Bread, How Did They Make It? Part IV: Markets, Merchants and the Tax Man”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-08-21.

May 19, 2023

QotD: The horses of the Eurasian Steppe

The horse is native to the Eurasian Steppe – that is where it evolved and was first domesticated, though the earliest domesticated wild horses were much smaller and weaker (but more robust and self-sufficient) than modern horses. The horse was first domesticated here, on the Eurasian Steppe, by the nomadic peoples there around 3,700 BCE. It seems likely that the nomads of the steppe were riding these horses more or less from the get-go (based on bridle and bit wear patterns on horse bones), but the domesticated horse first shows up in the settled Near East as chariotry (rather than cavalry) around 2000 BCE; true cavalry won’t become prominent in the agrarian world until after the Late Bronze Age Collapse (c. 1200 BCE).

I wanted to start by stressing these dates just to note that the peoples of the Eurasian Steppe had a long time to adapt themselves to a nomadic lifestyle structured around horses and pastoralism, which, as we’ve seen, was not the case for the peoples of the Americas, whose development of a sustainable system of horse nomadism was violently disrupted.

That said, the steppe horse (perhaps more correctly, the steppe pony) is not quite the same as modern domesticated horses. The sorts of horses that occupy stables in Europe or America are the product of centuries of selective breeding for larger and stronger horses. Because those horses were stable fed (that is, fed grains and hay, in addition to grass), they could be bred much larger what a horse fed entirely on grass could support (with the irony that many of those breeds of horses, if released into the wild in their native steppe, would be unable to subsist themselves), because processed grains have much higher nutrition and calorie density than grass. So while most modern horses range between c. 145-180cm tall, the horses of the steppe were substantially smaller, 122-142cm. Again, just to be clear, this is essential because the big chargers and work-horses of the agrarian world cannot sustain themselves purely on grass and the Steppe nomad needs a horse which can feed itself (while we’re on horse-size, mustangs, the feral horses of the Americas, generally occupy the low-end of the horse range as well, typically 142-152cm in height – even when it is clear that their domesticated ancestors were breeds of much larger work horses).

Bret Devereaux, “That Dothraki Horde, Part II: Subsistence on the Hoof”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-12-11.

April 4, 2023

History Summarized: the Ancient Greek Post-Apocalypse

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 31 Mar 2023Turns out the “Studio Ghibli Post-Apocalypse” aesthetic has a historical basis in ancient Greek history’s Bronze Age Collapse, long Dark Age, and slow re-emergence into the Polis Age. I don’t know if I’d call the process pleasant, but it sure as hell is a vibe.

GO READ THE ILIAD: https://bookshop.org/p/books/the-ilia… — We enjoy the Fagles translation, as it’s the typical classroom and library standard, but if you want a real treat, try the Alexander Pope edition from the 1700s that’s written entirely in RHYME. THE DAMN THING RHYMES!!!

SOURCES & Further Reading:

“The Age of Heroes” and “Delphi and Olympia” from Ancient Greek Civilization by Jeremy McInerney – “Dark Age and Archaic Greece” from The Foundations of Western Civilization by Thomas F. X. Noble – “Dark Age and Archaic Greece” from The Greek World: A Study of History and Culture by Robert Garland “The Greeks: A Global History” by Roderick Beaton, “The Greeks: An Illustrated History” by Diane Cline, Metropolitan Museum “Geometric Art in Ancient Greece” https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/grg… also have a degree in Classical Studies

(more…)

March 9, 2023

QotD: Iron ore mining before the Industrial Revolution

Finding ore in the pre-modern period was generally a matter of visual prospecting, looking for ore outcrops or looking for bits of ore in stream-beds where the stream could then be followed back to the primary mineral vein. It’s also clear that superstition and divination often played a role; as late as 1556, Georgius Agricola feels the need to include dowsing in his description of ore prospecting techniques, though he has the good sense to reject it.

As with many ancient technologies, there is a triumph of practice over understanding in all of this; the workers have mastered the how but not the why. Lacking an understanding of geology, for instance, meant that pre-modern miners, if the ore vein hit a fault line (which might displace the vein, making it impossible to follow directly) had to resort to sinking shafts and exploratory mining an an effort to “find” it again. In many cases ancient miners seem to have simply abandoned the works when the vein had moved only a short distance because they couldn’t manage to find it again. Likewise, there was a common belief (e.g. Plin. 34.49) that ore deposits, if just left alone for a period of years (often thirty) would replenish themselves, a belief that continues to appear in works on mining as late as the 18th century (and lest anyone be confused, they clearly believe this about underground deposits; they don’t mean bog iron). And so like many pre-modern industries, this was often a matter of knowing how without knowing why.

Once the ore was located, mining tended to follow the ore, assuming whatever shape the ore-formation was in. For ore deposits in veins, that typically means diggings shafts and galleries (or trenches, if the deposit was shallow) that follow the often irregular, curving patterns of the veins themselves. For “bedded” ore (where the ore isn’t in a vein, but instead an entire layer, typically created by erosion and sedimentation), this might mean “bell pitting” where a shaft was dug down to the ore layer, which was then extracted out in a cylinder until the roof became unstable, at which point the works were back-filled or collapsed and the process begun again nearby.

All of this digging had to be done by hand, of course. Iron-age mining tools (picks, chisels, hammers) fairly strongly resemble their modern counterparts and work the same way (interestingly, in contrast to things like bronze-age picks which were bronze sheaths around a wooden core, instead of a metal pick on a wooden haft).

For rock that was too tough for simple muscle-power and iron tools to remove, the typical expedient was “fire-setting“, which remained a standard technique for removing tough rocks until the introduction of explosives in the modern period. Fire-setting involves constructing a fuel-pile (typically wood) up against the exposed rock and then letting it burn (typically overnight); the heat splinters, cracks and softens the rock. The problem of course is that the fire is going to consume all of the oxygen and let out a ton of smoke, preventing work close to an active fire (or even in the mine at all while it was happening). Note that this is all about the cracking and splintering effect, along with chemical changes from roasting, not melting the rock – by the time the air-quality had improved to the point where the fire-set rock could be worked, it would be quite cool. Ancient sources regularly recommend dousing these fires with vinegar, not water, and there seems to be some evidence that this would, in fact, render the rock easier to extract afterwards.

By the beginning of the iron age in Europe (which varies by place, but tends to start between c. 1000 and c. 600 BC), the level of mining sophistication that we see in preserved mines is actually quite considerable. While Bronze Age mines tend to stay above the water-table, iron-age mines often run much deeper, which raises all sorts of exciting engineering problems in ventilation and drainage. Deep mines could be drained using simple bucket-lines, but we also see more sophisticated methods of drainage, from the Roman use of screw-pumps and water-wheels to Chinese use of chain-pumps from at least the Song Dynasty. Ventilation was also crucial to prevent the air becoming foul; ventilation shafts were often dug, with the use of either cloth fans or lit fires at the exits to force circulation. So mining could get very sophisticated when there was a reason to delve deep. Water might also be used to aid in mining, by leading water over a deposit and into a sluice box where the minerals were then separated out. This seems to have been done mostly for mining gold and tin.

Bret Devereaux, “Iron, How Did They Make It? Part I, Mining”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-09-18.

December 31, 2022

Coming of the Sea Peoples: Part 6 – Crete and the Minoans

seangabb

Published 6 Jul 2021The Late Bronze Age is a story of collapse. From New Kingdom Egypt to Hittite Anatolia, from the Assyrian Empire to Babylonia and Mycenaean Greece, the coming of the Sea Peoples is a terror that threatens the end of all things. Between April and July 2021, Sean Gabb explored this collapse with his students. Here is one of his lectures. All student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

December 27, 2022

Coming of the Sea Peoples: Part 5 – The Hittites

seangabb

Published 6 Jul 2021[Unfortunately, parts 3 and 4 of this lecture series were not uploaded due to sound issues with the recording].

The Late Bronze Age is a story of collapse. From New Kingdom Egypt to Hittite Anatolia, from the Assyrian Empire to Babylonia and Mycenaean Greece, the coming of the Sea Peoples is a terror that threatens the end of all things. Between April and July 2021, Sean Gabb explored this collapse with his students. Here is one of his lectures. All student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

December 20, 2022

Coming of the Sea Peoples: Part 2 – The Old and New Chronology of the Bronze Age

seangabb

Published 2 May 2021The Late Bronze Age is a story of collapse. From New Kingdom Egypt to Hittite Anatolia, from the Assyrian Empire to Babylonia and Mycenaean Greece, the coming of the Sea Peoples is a terror that threatens the end of all things. Between April and July 2021, Sean Gabb explored this collapse with his students. Here is one of his lectures. All student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

December 16, 2022

Coming of the Sea Peoples: Part 1 – Prelude

seangabb

Published 1 May 2021The Late Bronze Age is a story of collapse. From New Kingdom Egypt to Hittite Anatolia, from the Assyrian Empire to Babylonia and Mycenaean Greece, the coming of the Sea Peoples is a terror that threatens the end of all things. Between April and July 2021, Sean Gabb explored this collapse with his students. Here is one of his lectures. All student contributions have been removed.

More by Sean Gabb on the Ancient World: https://www.classicstuition.co.uk/

Learn Latin or Greek or both with him: https://www.udemy.com/user/sean-gabb/

His historical novels (under the pen name “Richard Blake”): https://www.amazon.co.uk/Richard-Blak…

November 12, 2022

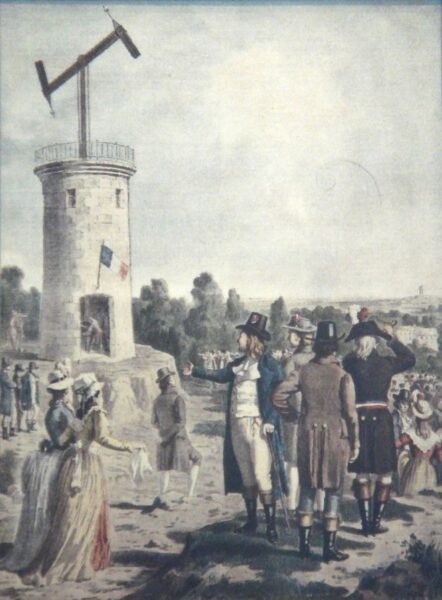

Long distance communication in the pre-modern era

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes considers why the telegraph took so long to be invented and describes some of the precursors that filled that niche over the centuries:

… I’ve also long wondered the same about telegraphs — not the electric ones, but all the other long-distance signalling systems that used mechanical arms, waved flags, and flashed lights, which suddenly only began to really take off in the eighteenth century, and especially in the 1790s.

What makes the non-electric telegraph all the more interesting is that in its most basic forms it actually was used all over the world since ancient times. Yet the more sophisticated versions kept on being invented and then forgotten. It’s an interesting case because it shows just how many of the budding systems of the 1790s really were long behind their time — many had actually already been invented before.

The oldest and most widely-used telegraph system for transmitting over very long distances was akin to Gondor’s lighting of the beacons, capable only of communicating a single, pre-agreed message (with flames often more visible at night, and smoke during the day). Such chains of beacons were known to the Mari kingdom of modern-day Syria in the eighteenth century BC, and to the Neo-Assyrian emperor Ashurbanipal in the seventh century BC. They feature in the Old Testament and the works of Herodotus, Aeschylus, and Thucydides, with archaeological finds hinting at even more. They remained popular well beyond the middle ages, for example being used in England in 1588 to warn of the arrival of the Spanish Armada. And they were seemingly invented independently all over the world. Throughout the sixteenth century, Spanish conquistadors again and again reported simple smoke signals being used by the peoples they invaded throughout the Americas.

But what we’re really interested in here are systems that could transmit more complex messages, some of which may have already been in use by as early as the fifth century BC. During the Peloponnesian War, a garrison at Plataea apparently managed to confuse the torch signals of the attacking Thebans by waving torches of their own — strongly suggesting that the Thebans were doing more than just sending single pre-agreed messages.

About a century later, Aeneas Tacticus also wrote of how ordinary fire signals could be augmented by using identical water clocks — essentially just pots with taps at the bottom — which would lose their water at the same rate and would have different messages assigned to different water levels. By waving torches to signal when to start and stop the water clocks (Ready? Yes. Now start … stop!), the communicator could choose from a variety of messages rather than being limited to one. A very similar system was reportedly used by the Carthaginians during their conquests of Sicily, to send messages all the way back to North Africa requesting different kinds of supplies and reinforcement, choosing from a range of predetermined signals like “transports”, “warships”, “money”.

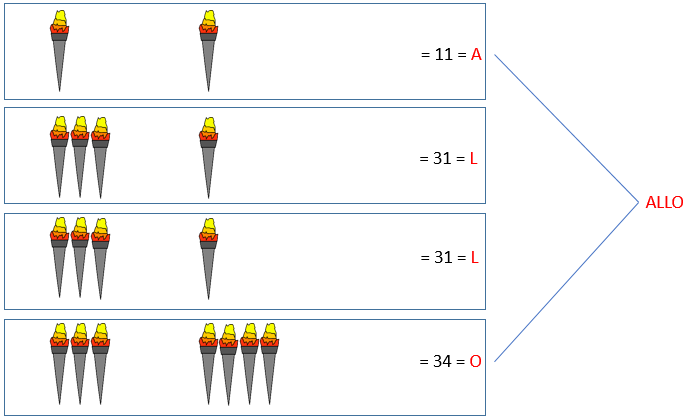

Diagram of a fire signal using the Polybius cipher.

Created by Jonathan Martineau via Wikimedia Commons.By the second century BC, a new method had appeared. We only know about it via Polybius, who claimed to have improved on an even older method that he attributed to a Cleoxenus and a Democleitus. The system that Polybius described allowed for the spelling out of more specific, detailed messages. It used ten torches, with five on the left and five on the right. The number of torches raised on the left indicated which row to consult on a pre-agreed tablet of letters, while the number of torches raised on the right indicated the column. The method used a lot of torches, which would have to be quite spread out to remain distinct over very long distances. So it must have been quite labour-intensive. But, crucially, it allowed for messages to be spelled out letter by letter, and quickly.

Three centuries later, the Romans were seemingly still using a much faster and simpler version of Polybius’s system, almost verging on a Morse-like code. The signalling area now had a left, right, and middle. But instead of signalling a letter by showing a certain number of torches in each field all at once, the senders waved the torches a certain number of times — up to eight times in each field, thereby dividing the alphabet into three chunks. One wave on the left thus signalled an A, twice on the left a B, once in the middle an I, twice in the middle a K, and so on.

By the height of the Roman Empire, fire signals had thus been adapted to rapidly transmit complex messages over long distances. But in the centuries that followed, these more sophisticated techniques seem to have disappeared. The technology appears to have regressed.

October 28, 2022

History Summarized: Mycenaean Greece & the Bronze Age Collapse

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 24 Jun 2022I’m pronouncing Mycenaean & Mycenae with a hard “K” sound because that’s how it sounds in Greek, and I would not be so impolite as to mispronounce the name of the first Greek-speaking civilization in history. (The name of “Mycenae” can be spelled Μυκῆναι or Μυκήνη, and I’m using the first one: mee-KEE-neh)

(more…)