In Quillette, Jaspreet Singh Boparai tells the long-suppressed story of the counter-revolution centred in the Vendée and the genocidal repression that followed:

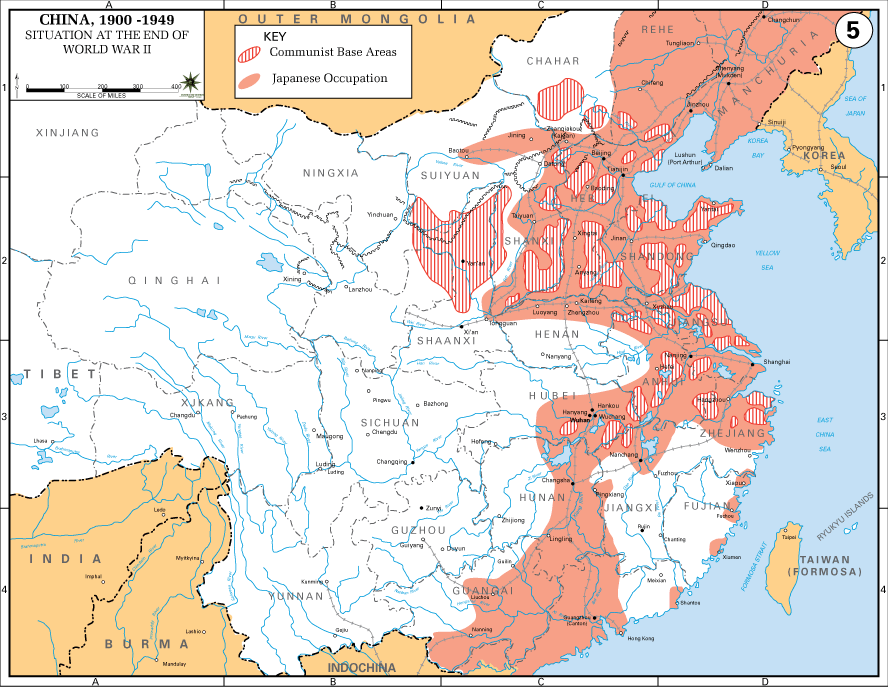

Map of the Vendée region of France in 1793. From page 123 of Francois-Severin Marceau (1769-1796) by Thomas George Johnson published in 1896 in London.

Via Wikimedia Commons.

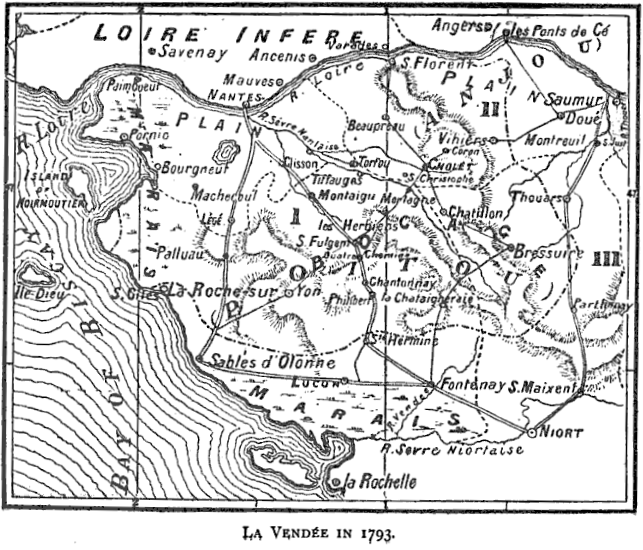

On March 4 2011, the French historian Reynald Secher discovered documents in the National Archives in Paris confirming what he had known since the early 1980s: there had been a genocide during the French Revolution. Historians have always been aware of widespread resistance to the Revolution. But (with a few exceptions) they invariably characterize the rebellion in the Vendée (1793–95) as an abortive civil war rather than a genocide.

In 1986, Secher published his initial findings in Le Génocide franco-français, a lightly revised version of his doctoral dissertation. This book sold well, but destroyed any chance he might have had for a university career. Secher was slandered by journalists and tenured academics for daring to question the official version of events that had taken place two centuries earlier. The Revolution has become a sacred creation myth for at least some of the French; they do not take kindly to blasphemers.

[…]

The Vendée is a region in the west of France whose residents became renowned for their piety after Protestants were driven out of the area in the wake of King Louis XIV’s Edict of Fontainebleau (1685). Throughout the 18th century, the Vendée was, culturally, politically and economically, a backwater. The closest major city, Nantes, remains noted for its role in the slave trade.

Vendéens seem to have welcomed the French Revolution, at least initially. Everybody was annoyed with high levels of taxation. Even the pious were fed up with what they had to pay to the Church. The problem was not so much with the clergy as with parish assemblies (fabriques), which controlled parish finances. Vendéens had little quarrel with the local nobility, who as a rule stayed in the region and knew the peasantry well. Few of them spent any time in Paris, Versailles or even Nantes. The nobles too resented centralized administration.

The revolutionary government was determined to break the remaining power of the Catholic church, and seized most of the church properties, followed by a secularization of the church hierarchy in France which was intended to turn the priests and bishops into civil servants loyal to the French state rather than to the Pope in Rome. Resistance to this was particularly strong in Nantes and the surrounding region, which encouraged the revolutionary government to shut down all churches that did not conform to state directives. At the same time, the government introduced conscription, which was even more fiercely opposed in the Vendée and triggered armed conflict.

The rebels’ volunteer army numbered between 25,000–40,000 peasants whose main fighting experience consisted of drunken brawls in village taverns. They had no uniforms; most wore “sabots” (wooden clogs) instead of boots. Yet they consistently managed to beat back well-armed, experienced professional soldiers. A few had hunting rifles and were excellent shots; but the vast majority were armed with pitchforks, shovels and hoes. When the Revolutionary forces retreated, the rebels went back home to attend to their farms so that their families would not starve.

Revolutionary generals did not expect them to fight so fiercely. Of course, the rebels had no reinforcements behind them, and they knew that if they did not repel the Revolutionaries their homes would be destroyed, and their families butchered. The Vendéens were not paid for their fighting. Their main rewards for winning a battle was not being slaughtered for a little while longer. Under the circumstances, their discipline was outstanding, as even the Revolutionary generals admitted.

But the resources of the rebels were few, and casualties could not be replaced, unlike the government’s forces, so the tide eventually turned against the outnumbered rebels.

It became customary to drown brigands naked, not merely so that the Revolutionaries could help themselves to the Vendéens’ clothes, but also so that the younger women among them could be raped before death. Drownings spread far beyond Nantes: on 16th December, General Marceau sent a letter to the Revolutionary Minister of War triumphantly announcing, among other victories, that at least 3,000 non-combatant Vendéen women had been drowned at Pont-au-Baux.

The Revolutionaries were drunk with blood, and could not slaughter their brigand prisoners fast enough — women, children, old people, priests, the sick, the infirm. If the prisoners could not walk fast enough to the killing grounds, they were bayoneted in the stomach and left on the ground to be trampled by other prisoners as they bled to death.

General Westermann, one of the Revolution’s most celebrated soldiers, noted with satisfaction that he arrived at Laval on December 14 with his cavalry to see piles of cadavers — thousands of them — heaped up on either side of the road. The bodies were not counted; they were simply dumped after the soldiers had a chance of strip them of any valuables (mainly clothes).

The final death toll could only be an educated guess:

Reynald Secher estimates that just over 117,000 Vendéens disappeared as a result of the brigands’ rebellion, out of a population of just over 815,000. This amounts to roughly one in seven Vendéens fatally affected by military actions and the Crusade for Liberty. Though some areas lost half their population or more, with notably heavy losses at Cholet, which lost three fifths of its houses as well as the same proportion of its people. Colleges, libraries and schools were destroyed as well as churches, private houses, farms, workshops and places of business. The Vendée lost 18 percent of its private houses; a quarter of the communes in Deux-Sèvres saw the destruction of 50 percent or more of all habitable buildings. Other consequences of the Crusade for Liberty included a widespread epidemic of venereal disease.