Forgotten Weapons

Published Jan 12, 2024Today we return to Guadalcanal, to the site of the last actions of the campaign. For the Japanese, the defeat at Edson’s Ridge (aka Bloody Ridge) forced a disastrous and uncoordinated retreat into the jungle. With their supply lines destroyed, Japanese troops largely moved west on the island, away from American positions and in search of food. This would eventually bring them to Cape Esperance, where a rearguard force was landed, and some 10,652 Japanese soldiers were successfully evacuated on fast-moving destroyers over the course of several nights in early February, 1943.

On the American side, Army troops landed to relieve the Marines. In January and into early February they ran what was considered a mopping-up campaign west, including landings on the far west end of the island beyond Esperance. The intention was to encircle the remaining Japanese forces, under the assumption that the destroyer activity was landing fresh troops. Instead, when the American forces joined up at Cape Esperance it was an anticlimactic end to the fighting, as all they found were remnants of equipment that had been left on the beaches.

(more…)

April 20, 2024

Cape Esperance and the Japanese Evacuation of Guadalcanal

April 8, 2024

Beecher’s Bible: A Sharps 1853 from John Brown’s Raid on Harpers Ferry

Forgotten Weapons

Published Jan 8, 2024On October 16, 1859 John Brown and 19 men left the Kennedy farmhouse and made their way a few miles south to the Harpers Ferry Arsenal. They planned to seize the Arsenal and use its arms — along with 200 Sharps 1853 carbines and 1,000 pikes they had previously purchased — to ignite and arm a slave revolt. Brown was a true fanatic for the abolitionist cause, perfectly willing to spill blood for a just cause. His assault on the Arsenal lasted three days, but failed to incite a rebellion. Instead of attracting local slaves to his banner, he attracted local militia and the US Marines. His force was besieged in the arsenal firehouse, and when the Marines broke through the doors they captured five surviving members of the Brown party, including Brown himself. All five were quickly tried and found guilty of murder, treason, and inciting negroes to riot. They were sentenced to death, and hanged on December 2, 1859.

Most of Brown’s 200 Sharps carbines were left in the farmhouse hideout, to be distributed when the insurrection took hold. These were found by local militia, among them the Independent Greys, and some were kept as souvenirs — including this example.

There is an intriguing historical question as to whether Brown’s raid was ultimately good for the country or not. It was extremely divisive at the time, and it can be argued that the raid was a major factor leading to Lincoln’s election and the Civil War. Could slavery have been abolished without the need for a cataclysmic war if John Brown had not fractured the Democratic Party? To what extent is killing for a cause justifiable? Do the ends always justify the means? John Brown had no doubts about his answers to these questions … but maybe he should have.

(more…)

February 4, 2024

Johnson LMG: History & Disassembly

Forgotten Weapons

Published Feb 29, 2016The Johnson light machine gun is one of the lesser-known US military machine guns of WWII, although it seems to have been very popular with all those who used it in combat. Melvin Johnson made a commendable attempt to get his rifles adopted by the US military, but was unable to unseat the M1 Garand as American service rifle. However, he did make a significant sale of both rifles and light machine guns to the Dutch colonial army.

By the time those Dutch guns were ready to ship, however, the Japanese had overrun most of the Dutch islands. The guns were thus basically sitting on the docks with nowhere to go, and at that point the US Marine Corps took possession of them. Because of their short recoil action and quickly removable barrels, the Johnson guns were ideal for airborne Paramarines, and saw use in the Pacific with these forces. They were also used by the joint US/Canadian First Special Service Force in Italy.

In many ways, the Johnson LMG is similar to the German FG-42, although with more emphasis on full-auto use instead of shoulder rifle use. It fired from a closed bolt in semiauto and from an open bolt in full auto, and had a bipod both effective, light, and easily detachable. Overall the Johnson is a light, handy, and very easily dismantled weapon, and its popularity with combat troops seems well deserved.

January 5, 2024

Pacific Theater USMC-Modified Johnson M1941 Rifle

Forgotten Weapons

Published 25 Aug 2023Johnson M1941 rifles were used in limited numbers by the US Marine Corps in the Pacific theater of World War Two, but they were used — and generally well liked. Interestingly, there was a fairly common field modification done by the Marines, and that was to cut off the front sight wings, and sometimes cut the rear aperture into a deep V-notch or a flat U-notch style. This particular ex-Marine rifle shows both of these modifications.

(more…)

November 28, 2023

“This was a document from a parallel universe with familiar-sounding people and places, but a totally bizarre worldview and culture”

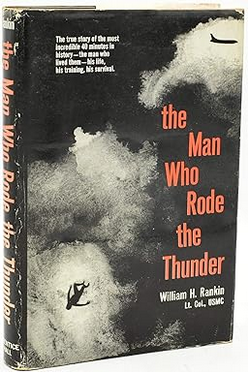

In the latest addition to Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, John Psmith reviews The Man Who Rode the Thunder, by William H. Rankin:

Like many little boys, I loved learning lists of things. One day it was clouds. How could I not love them? The names were fluffy and Latinate, delicate little words like “cumulus” and “cirrus” that sounded like they might float away on a puff of wind. But there was also a structure to the words, intimations and hints of taxonomy. Was the relationship of an altocumulus to an altostratus the same as that of a cirrocumulus to a cirrostratus? I wasn’t sure, but it seemed likely! So here I had not just a heap of words, but something more like a map to making sense of a new part of the world.

So I learned the names of all the clouds, but I quickly got bored of most of them. Only one of them held my attention, but it made up for the rest by becoming an obsession. Yes, it was the mighty cumulonimbus, the towering, violent monster that heralds the approach of a thunderstorm. By then I had already met plenty of them — one of my earliest memories is of huddling with my mother in the room of our house that was farthest from any exterior walls, while lightning struck again and again and again, the echoes of the previous thunderclap still reverberating off the landscape when the next one began. What, I wondered, would it be like to be inside one?

There’s one man who knows. His name is Colonel William H. Rankin, and he fell through a thunderstorm and lived to tell the tale. After his ordeal Rankin published a memoir that was a bestseller in the early ’60s, but is out of print today. If you click the Amazon link at the top of this page, you will see that secondhand copies of the paperback edition go for about $150. If that’s too steep for you, I’m told that

Good Samaritanscommunists have uploaded high-quality scans of the book to various nefarious and America-hating websites, but this is a patriotic Substack and we would never condone that sort of behavior. Be warned!I sought out and read Rankin’s memoir for the part where he falls through a cloud, so I was planning on skimming and/or skipping the hundred or so pages where he narrates his life and career up to that point. When I actually cracked open the

They say you should read books to broaden yourself, to learn about foreign peoples and about cultures not your own. I was unprepared for late 1950s America being as foreign as it turned out to be. There’s a whole genre comprised of parodying the supposed mid-century American combo of sunny faith in scientific progress, squeaky-clean public morality, and blithe indifference to the horrors of industrial warfare. In my own reading and watching, I had only ever encountered the parodies, never the genuine article, until I read this book. Rankin’s memoir exudes gee-whiz enthusiasm from every pore. He is patriotic without a trace of irony, giddy as a schoolboy about advances in jet propulsion, and then uses a totally unchanged tone of giddiness and enthusiasm to describe melting hundreds of Korean peasants with napalm.

Reading this stuff fills me with the same feeling of vertigo that I get reading about Bronze Age Greek warriors — here is a human being just like me, but inhabiting a cultural, spiritual, and memetic universe so different from mine. Are we the same species? If we were to meet each other would we even be able to communicate? Or perhaps every age has had people like him and people like me, and all that’s changed is that the dominant mode of social interaction shifted from favoring one of us to the other. After all, I know people today who are incapable of irony or reflection. For instance, TSA agents. Was 1950s America an entire society of TSA agents? And if so, what am I to make of the fact that in so many ways it seems to have been more functional than America today?

October 28, 2023

Smith versus Smith: US Army/Marine relations in 1944

World War Two

Published 27 Oct 2023When Marine Corps General Holland “Howling Mad” Smith removed Infantry General Ralph Smith from command in 1944 during the Battle of Saipan, it began a controversy that soon snowballed, threatening to sabotage Army-Marine relations at a time when cooperation was the key to victory.

(more…)

September 8, 2023

Johnson M1941 rifle

Forgotten Weapons

Published 8 Dec 2013Melvin Johnson was a gun designer who felt that the M1 Garand rifle had several significant flaws — so he developed his own semiauto .30-06 rifle to supplement the M1. His thought was that if problems arose with the M1 in combat, production of his rifle could provide a continuing supply of arms while problems with the M1 were worked out. The rifle he designed was a short-recoil system with a multi-lug rotating bolt (which was the direct ancestor of the AR bolt design). When the Johnson rifle was tested formally alongside the M1, the two were found to be pretty much evenly matched — which led the Army to dismiss the Johnson. If it wasn’t a significant improvement over the Garand, Ordnance didn’t see the use in siphoning off resources to produce a second rifle.

The Johnson had some interesting features — primarily its magazine design. It used a fixed 10-round rotary magazine, which could be fed by 5-round standard stripper clips or loose individual cartridges. It could also be topped up without interfering with the rifle’s action, unlike the M1. On the other hand, it was not well suited to using a bayonet, since the extra weight on the barrel was liable to cause reliability problems (since the recoil action has to be balanced for a specific reciprocating mass). Johnson thought bayonets were mostly useless, but the Army used the issue as a rationale to dismiss the Johnson from consideration.

However, Johnson was able to make sales of the rifle to the Dutch government, which was in urgent need of arms for the East Indies colonies. This is where the M1941 designation came from — it was the Dutch model name. Only a few of the 30,000 manufactured rifles were delivered before the Japanese overran the Dutch islands, rendering the rest of the shipment moot.

At this point, Johnson was also working to interest the newly-formed Marine Paratroop battalions in a light machine gun version of his rifle. The Paramarines needed an LMG which could be broken down for jumping, light enough for a single man to effectively carry, and quick to reassemble upon landing. The Johnson LMG met these requirements extremely well, and was adopted for the purpose. The Paramarines were being issued Reising folding-stock submachine guns in addition to the Johnson LMGs, and they found the Reisings less than desirable. Someone noticed that thousands of M1941 Johnson rifles (which could also have their barrel quickly and easily removed for compact storage) were effectively sitting abandoned on the docks, and the Para Marines liberated more than a few of them. These rifles were never officially on the US Army books, but they were used on Bougainville and a few other small islands.

July 18, 2023

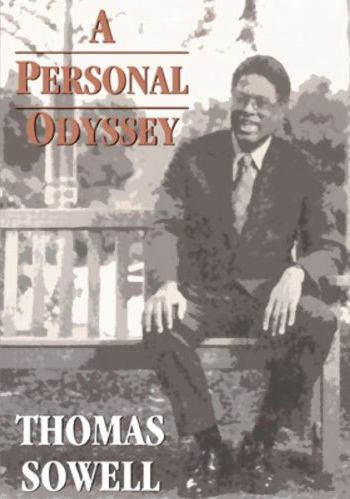

Life lessons from Thomas Sowell’s memoir

Rob Henderson took a lot away from his recent reading of Thomas Sowell’s A Personal Odyssey, including some fascinating lessons from Sowell’s time in the US Marine Corps:

Trust people who value being honest more than being nice.

As the Korean War intensified, Sowell was drafted into the Marine Corps. He notes that color did not matter, as all new recruits were treated with equal disdain. Sowell describes his life in the Marine barracks in Pensacola. There were two non-commissioned officers permanently stationed to oversee the young marines. One was Sergeant Gordon, “a genial, wisecracking guy who took a somewhat relaxed view of life”. The other was Sergeant Pachuki, “a disciplinarian who spoke in a cutting and ominous way” and was always “impeccably dressed”.

Sowell and his peers preferred Sergeant Gordon, as he was more easygoing. Sowell had to go into town to pick up a package. Sowell asked his Chief Petty Officer if he could leave the base to retrieve his package. Sowell received permission.

Later, while Sowell was not on base, he was marked as absent and was accused of being AWOL (absent without leave), a serious offense. Sowell knew Sergeant Gordon, the nice one, had overheard him asking for permission to leave the base. Gordon denied having heard anything, and told Sowell, “You’re just going to have to take your punishment like a man”. Gordon fretted that if he crossed the higher-ups, he would be reassigned to fight in Korea.

But unasked, Sergeant Pachuki came forward and spoke with the colonel, explaining the situation. As a result, Sowell was exonerated and returned back to his duties.

Referring to Gordon, the “nice” sergeant who betrayed him, Sowell writes, “People who are everybody’s friend usually means they are nobody’s friend”.

A “free good” is a costless good that is not scarce, and is available without limit.

Sowell would regularly needle Sergeant Grover, another member who outranked him.

Here’s the excerpt:

Some were surprised that I dared to give Sergeant Grover a hard time, on this and other occasions, especially since he was a nasty character to deal with. Unfortunately for him, I knew that he was going to give me as hard a time as he could, regardless of what I did. That meant it didn’t really cost me anything to give him as hard a time as I could. Though I didn’t realize it at the time, I was already thinking like an economist. Giving Sergeant Grover a hard time was, in effect, a free good and at a zero price my demand for it was considerable.

Sowell learned he could receive something he enjoyed (pleasure at provoking Grover) in exchange for nothing.

Much of what you see has been carefully curated with an agenda in mind.

One of Sowell’s assignments in the Marine Corps was as a Duty Photographer on base. One day after submitting some of his photos, Sowell had the following exchange with the public information office sergeant:

“They are good pictures, he said. “But they do not convey the image that the public information office wants conveyed.”

“What’s wrong with them?” I asked.

“Well, take that picture of the reservists walking across the little wooden bridge carrying their duffle bags.”

“Yeah. What’s wrong with it?”

“The men in that picture are perspiring. You can see the damp spots on their uniforms.”

“Well, if you carry a duffle bag on a 90-degree day, you are going to sweat.”

“Marines do not sweat in public information photographs.”

“Okay, what was wrong with the picture of the reservists picking up shell casings after they had finished firing? That was one of my favorites.”

“Marines do not perform menial chores like that, in our public relations image.”

“But all these photos showed a very true picture of the reservists’ summer here.”

“We’re not here to tell the truth, Sowell,” he said impatiently. “We are here to perpetuate the big lie. Now, the sooner you understand that, the better it will be for all of us.”

When I visited the Air Force recruiter in high school, I saw the brochures with images of well-groomed airmen in their dress blues graduating from basic training. I had no knowledge that much of that training would involve mind-numbing minutia. I suppose this is true for other career fields too. You see radiant coverage of academic research in legacy media outlets, or fun twitter threads outlining interesting research findings. You see the brand new hardcover book with all the glowing blurbs and reviews. You don’t see all the drudgery of research or writing behind the scenes.

Sometimes, it doesn’t pay to have too big a reputation.

Sowell and his fellow marines would sometimes have impromptu boxing matches around the barracks on base. One day Sowell was up against another guy and threw a sloppy right hand. The guy stumbled back, tripped, and fell to the ground. Although Sowell had swung and missed, witnesses thought he had knocked the other guy out.

Later, Sowell went up against another guy named Douglas. Douglas relentlessly came at Sowell and gave him a serious beating. Douglas told Sowell afterwards that the reason he was so aggressive was that he feared Sowell’s “one punch” could turn the fight around at any time. “Sometimes,” Sowell writes, “it doesn’t pay to have too big a reputation.”

June 6, 2023

QotD: “A second front” in 1942

I have been reading the recent biography of the British CIGS Alanbrooke, and been struck by the clear and concise explanation of the differences between the British and Americans over the “second front” in Europe, and when it could be.

[…]

A plan put together for the incredibly unlikely event of sudden German collapse, was Sledgehammer. This was the understanding of Sledgehammer adopted by most Americans. A very limited offensive by very inadequate forces, which could only succeed had Germany already gone close to collapse. Given the circumstances this was somewhat delusional, but it never hurts to plan for eventualities, and the British were happy to go along with this sort of plan.

[…]

Any attempt at Sledgehammer would of course have failed. The German army had not yet been bled dry on the Eastern front, and the Luftwaffe was still a terrifying force which could be (and regularly was) easily moved from Russian mud to Mediterranean sunshine and back again in mere weeks. Even ignoring the opposition, the British were gloomily aware that the Americans had not a clue of the complexities of such a huge amphibious operation. At the time of discussion – May 1942 – the British were using their first ever Landing Ship Tanks and troopships equipped with landing craft to launch a brigade-size pre-emptive operation against the Vichy French on Madagascar. (Another move many historians think was useless. But coming only months after the Vichy had invited the Japanese into Indo-China – fatally undermining the defenses of Malaya – and the Germans into Syria, it was probably a very sensible precaution. Certainly Japanese submarines based in Madagascar [could] have finally caused the allies to lose the war at sea!)

The British deployed two modern aircraft carriers, and a fleet of battleships, cruisers, destroyers and escorts and a large number of support ships, on this relatively small operation. It was the first proper combined arms amphibious operation of the war, and was very helpful to the British to reveal the scale of amphibious transport needed for future operations. By contrast the US Marines hit Guadalcanal six months later from similar light landing craft, and with virtually the same Great War-vintage helmets and guns that the ANZACS had used at Gallipoli. Anyone who reads the details of the months of hanging on by the fingernails at Guadalcanal against very under-resourced Japanese troops, will be very grateful that the same troops did not have to face veteran German Panzer divisions for several years.

So I do not know of any serious historian who imagines that an invasion of France in 1942 could have led to anything except disaster. There are no serious generals who thought it either. (Only Marshall and his “yes-man” Eisenhower consistently argued that it might be possible. And Eisenhower later came to realise – when he was in charge of his third or fourth such difficult operation – that his boss was completely delusional in his underestimation of the difficulties involved. See Dear General: Eisenhower’s Wartime Letters to Marshall for Eisenhower’s belated attempts to quash Marshalls tactical ignorance about parachute drops and dispersed landings for D-Day.)

In practice no matter how much Marshall pushed for it, only British troops were availabe for such a sacrificial gesture, and the British were not unnaturally reluctant to throw away a dozen carefully nurtured and irreplaceable divisions on a “forlorn hope”, when they would prefer to save them for a real and practical invasion … when circumstances changed enough to make it possible.

Unfortunately Roosevelt told the Soviet foreign minister Molotov that “we expect the formation of a second front this year”, without asking even Marshall, let alone wihtout consulting his British allies who would have to do it with virtually no American involvement. The British Chiefs of Staff only had to show Churchill the limited numbers of landing craft that could be available, and the limited number of troops and tanks they could carry, to make it clear that this was ridiculous. Clearly this stupidity was just another example of Roosevelt saying stupid things without asking anyone (like “unconditional surrender”) that did so much to embitter staff relations during the war, and internationaly relations postwar. But it seems likely that the British refusal to even consider such nonsense was taken by Marshall and Stimson as a sample of the British being duplicitous about “examining planning options”.

The British fixed on a “compromise” to pretend that a “second front” could be possible. North Africa, could be conquered without prohibitive losses. It was not ideal, and in practical terms not even very useful. But it might satisfy the Americans and the Russians. Nothing else could.

Marshall in particular spent the rest of the war believing that when the British assessment clearly demonstrated that action in Europe was impractical and impossible, they had just been prevaricating to get what they always intended: operations in the Med. In some ways he was correct. The British had done the studies on France despite thinking that it was unlikely they would be practical, and were proved right. Marshall and Eisenhower had just deluded themselves into thinking an invasion might be practical, and could not accept that there was not a shred of evidence in favour of their delusion.

Nigel Davies, “The ‘Invasion of France in 1943’ lunacy”, rethinking history, 2021-06-21.

May 5, 2023

Alligator Creek: America Learns to Fight the Japanese

Forgotten Weapons

Published 7 Jan 2023The Battle of Alligator Creek (aka Battle of the Tenaru) was a formative moment in the American World War Two psyche. After making an unopposed landing on Guadalcanal and taking its mostly-completed airfield at minimal cost, the US Marines had to defend their permitter on the night of August 21st, 1942.

Colonel Kiyonoa Ichiki was sent from the Japanese base at Truk with about 900 tough veteran soldiers to push the Marines off the airfield. These men had originally been slated to assault Midway Island, but the Japanese naval defeat there forced a change in plans. Ichiki was overconfident, and more concerned about retaking the islands of Tulagi, Gavutu, and Tanambogo across the straights, where Japan’s main base in the area had also been captured by Marine Raiders. Marching up the coastline towards Henderson Field, Ichiki’s men hit the thin single strand of Marine barbed wire about about 1:30am on the morning of there 21st. An intense firefight erupted, with the well dug-in Marine positions opening up with .30 caliber and .50 caliber machine guns, small arms, and 37mm canister rounds.

The fighting continued after daybreak, with Ichiki’s men digging in on the east bank of Alligator Creek. The Marines launched a two prong counterattack, with one force crossing the Creek inland and advancing down the east bank while a second group, including several Stuart light tanks, advanced across the sandbar. These two groups linked up in the early afternoon of the 21st, almost completely annihilating the Ichiki Detachment.

This was the first real land combat between American and Japanese forces in which American soldiers were able to report back on their experience. It was here that the US military as an institution learned that the Japanese would die rather than surrender, and this engagement set the American expectations for the rest of the Pacific campaign.

(more…)

April 29, 2023

Okinawa 1945: Planning Operation ICEBERG

Army University Press

Published 7 Dec 2021On 1 April 1945, U.S. forces invaded the Japanese home island of Okinawa. It was the largest joint amphibious assault mounted during World War II in the Pacific Theater. The invasion of Okinawa was the culmination of three years of operations in the Pacific against Imperial Japan. The film explores the planning and preparation for Operation ICEBERG from September 1944 to 1 April 1945.

“Okinawa 1945: Planning Operation ICEBERG” examines the U.S. Army operations process as well as planning by echelon from field army, corps, and division with special emphasis on current Joint doctrine. This film is the first in a two-part series covering Operation ICEBERG and the U.S. Tenth Army’s securing of Okinawa.

(more…)

April 19, 2023

The USMC finds a new mission after WW1

Another excerpt from John Sayen’s Battalion: An Organizational Study of United States Infantry (unpublished, but serialized on Bruce Gudmundsson’s Tactical Notebook:

The 1919 demobilization was nearly as traumatic for the Marines as it was for the Army. Their numbers fell from a peak of 75,000 to about 1,000 officers and 16,000 enlisted in 1920. Authorized strength was 17,400. The 15 Marine regiments and at least three, probably four, machinegun battalions existing at the end of November 1918 had withered away to only five regiments and a couple of separate battalions (one artillery and one infantry) by the following August.

Marine commitments, however, remained heavy. The brigades in both Haiti and the Dominican Republic had their hands full suppressing new rebellions. Guard detachments were still needed for Navy bases and Navy ships. The number of men required for the latter duty had fallen by only 10% since 1918. The Marines also had to staff their own bases at Quantico, Parris Island, and San Diego and they had to find men to rebuild the advance base force as well. When these facts were brought to the attention of Congress in 1920 the latter increased the Marine Corps’ authorized strength to 1,093 officers and 27,400 enlisted but then approved funding for only 20,000.

[…]

The bulk of the Corps’ operating forces were still engaged in colonial police work in the Caribbean. However, the new Commandant, Major General John A. Lejeune, was prescient enough to realize that this would not last and that a much more permanent mission would be needed to secure his service’s future. Instead, Lejeune and his advisors concluded that the real mission of the Marine Corps was “readiness”. While this concept might seem trite, one should consider that the United States was and is primarily an insular power. Its standing army in 1920 served primarily as a garrison force and cadre for a much larger wartime citizen army. Little or none of it would be available for immediate use upon the outbreak of a major war beyond the troops already deployed to major US overseas possessions like the Philippines, Hawaii, or the Panama Canal.

Although the Army of 1920 seemed to have little idea about who its future adversaries were likely to be, the Navy had already fingered Japan as its most likely future opponent. Japan had the most powerful navy after the United States and Great Britain and Japanese-American animosity was growing. The Japanese resented the treatment of Japanese immigrants in California. Americans resented Japan’s high handed actions in China. The Japanese saw American criticism of Japan’s China policy as interference in Japan’s rightful sphere of influence. Any war fought against Japan would be primarily naval in character. However, post war disarmament treaties forbade improvements to any American fortresses west of Hawaii. The League of Nations had also mandated most of the central Pacific islands to Japanese control.

If it was to successfully engage the Japanese fleet, or to threaten Japan itself, the United States Navy would need bases in those central Pacific islands. Hawaii was too far away to be useful and the Philippines were too vulnerable to Japanese attack. Only an expeditionary force could seize and hold the central Pacific islands that the Navy needed and that expeditionary force would have to be ready to move whenever and wherever the Navy did. By staying “ready”, requiring only limited reserve augmentation and, being already under the Navy’s control, the Marine Corps would be much better positioned than the Army to provide this expeditionary force, at least during the critical early stages of the next war.*

* Heinl op cit pp. 253-254; Moskin op cit pp. 219-222; and Clifford op cit pp. 25-29 and 61-64.

April 18, 2023

Guadalcanal’s Red Beach Landing: America’s First Offensive in WW2

Forgotten Weapons

Published 24 Dec 2022After (formally) joining World War Two in the wake of Pearl Harbor, the United States endured a series of defeats at the hands of the Japanese. The Philippines garrison fell, Wake Island fell, Guam fell. British possessions in Southeast Asia teetered and fell as well — the campaign was not going well for the Allies.

The first American offensive of the war would come on August 7th, 1942 with the landing of the 1st and 5th Marines at Red Beach on Guadalcanal. Part of a multi-prong assault (the nearby Japanese bases on Tulagi and Gavutu/Tanambogo were also captured at the same time), the attack on Guadalcanal was made to secure the airstrip under Japanese construction there. If the island became an operational Japanese air base, Allied supply shipping to Australia would come under threat, and this could imperil the whole area of operations.

Fortunately for the Marines, US intelligence massively overestimated the Japanese force on Guadalcanal. It was in fact only a few hundred infantry, leading a work force of about 3,000 laborers (mostly Koreans). They thought the US landings were just a small raid, and dispersed into the jungle to wait for the US departure. Instead, the Marines were there to take the airfield and hold it. They were not, however, very well prepared. The Navy suffered a massive defeat in the waters off Guadalcanal the very next night, and would pull out of the area August 9th, leaving the Marines with dangerously low supplies of food, ammunition, and other essentials.

(more…)

April 10, 2023

US Army and Marine Corps deployments other than with the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF)

Another excerpt from John Sayen’s Battalion: An Organizational Study of United States Infantry currently being serialized on Bruce Gudmundsson’s Tactical Notebook shows where US infantry units (US Army and USMC) were deployed aside from those assigned to Pershing’s AEF on the Western Front in France:

Apart from the war in Europe, the principal military concern of the Wilson administration during 1917-18 was the protection of resources and installations considered vital to the war effort. The threat of German sabotage in the United States was taken very seriously. In addition, Mexico was still unstable politically and sporadic border clashes continued to occur into 1919. Mexican oil was also regarded as an essential resource and the troops stationed on the Mexican border were prepared to invade in order to keep it flowing. However, all the National Guard, National Army, and even the Regular Army regiments raised for wartime only were reserved for duty with the AEF. (The National Army 332nd and 339th Regiments did deploy to Italy and North Russia, respectively, but both remained under AEF command.) This left non-AEF assignments in the hands of the pre-war Regular Army regiments.

Out of 38 Regular infantry regiments available in 1917, 25 were on guard duty within the Continental United States or on the Mexican border and 13 garrisoned U.S. possessions overseas. Local defense forces raised in Hawaii and the Philippines eventually freed the pre-war regiments stationed in those places for duty elsewhere. By the end of the war the 15th Infantry in China, the 33rd and 65th (Puerto Rican) Infantry in the Canal Zone, and the 27th and 31st Infantry (both under the AEF tables) in Siberia were the only non-AEF regiments still overseas. Inside the United States state militia (non-National Guard) units and 48 newly raised battalions of “United States Guards” (recruited from men physically disqualified for overseas service) had freed 20 regiments from stateside guard duties, but not in time for any of them to fight in France.

Only twelve pre-war regiments actually saw combat in the AEF. Nine of them served with the early-arriving 1st, 2nd, and 3rd AEF Divisions. The other three were with the late arriving 5th and 7th Divisions. One more reached France with the 8th Division, but only days ahead of the Armistice. By this time, the Regular Army regiments had long ago been stripped of most of their pre-war men to provide cadre for new units. They were refilled with so many draftees that their makeup scarcely differed from those of the National Army.*

The situation with the Marines was similar to that of the Regular Army. Most Marine regiments had to perform security and colonial policing duties that kept them away from the “real” war in France. Also like the Army, the Marines made Herculean efforts to accommodate a flood of recruits, acquiring training bases at Quantico Virginia and Parris Island South Carolina, as their existing facilities became too crowded. The Second Regiment (First Provisional Brigade) continued to police Haiti while the Third and Fourth Regiments (Second Provisional Brigade) did the same for the Dominican Republic. The First Regiment remained at Philadelphia as the core of the Advance Base Force (ABF) but its role soon became little more than that of a caretaker of ABF equipment.

Although there was little danger from the German High Seas Fleet ABF units might still be needed in the Caribbean to help secure the Panama Canal and a few other critical points against potential attacks by German surface raiders or heavily armed “U-cruisers.” Political unrest was endangering both the Cuban sugar crop and Mexican oil. To address such concerns, the Marines raised the Seventh, Eighth, and Ninth Regiments as infantry units in August, October, and November 1917, respectively. The Seventh, with eight companies went to Guantanamo, Cuba, to protect American sugar interests. The Ninth Regiment (nine companies) and the headquarters of the Third Provisional Brigade followed. The Eighth Regiment with 10 companies, meanwhile, went to Fort Crockett near Galveston, Texas to be available to seize the Mexican oil fields with an amphibious landing, should the situation in Mexico get out of hand.

Three other rifle companies (possibly the ones missing from the Seventh and Ninth Regiments) occupied the Virgin Islands against possible raids by German submarines. In August 1918, the Seventh and Ninth Regiments expanded to 10 companies each. The situation in Cuba having subsided, the Marine garrison there was reduced to just the Seventh Regiment. The Ninth Regiment and the Third Brigade headquarters joined the Eighth at Fort Crockett.**

* Order of Battle of the United States Land Forces in the World War op cit pp. 310-314 and 1372-1379. A battalion of United States Guards was allowed 31 officers and 600 men. These units were recruited mainly from draftees physically disqualified for overseas service. The 27th and 31st Infantry when sent to Siberia were configured as AEF regiments, though they were never part of the AEF. Large numbers of men had to be drafted out of the 8th Division to build these two regiments up to AEF strength. This seriously disrupted the 8th Division’s organization.

** Order of Battle of the United States Land Forces in the World War op cit pp. 1372-78; Truman R. Strobridge, A Brief History of the Ninth Marines (Washington DC, Historical Division HQ US Marine Corps; revised version 1967) pp. 1-2; James S. Santelli, A Brief History of the Eighth Marines (Washington DC, Historical Division HQ US Marine Corps; 1976) pp. 1-3; and James S. Santelli, A Brief History of the Seventh Marines (Washington DC, Historical Division HQ US Marine Corps; 1980) pp. 1-5.

April 9, 2023

USMC units in the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) in France

Another interesting excerpt from John Sayen’s Battalion: An Organizational Study of United States Infantry currently being serialized on Bruce Gudmundsson’s Tactical Notebook discusses the role of the US Marine Corps on the Western Front as part of Pershing’s AEF:

“How Twenty Marines Took Bouresches” by Frank E. Schoonover.

Originally published in the Ladies’ Home Journal Vol. 24 No. 1, via Wikimedia Commons

The Fifth Regiment arrived in France in July 1917. Being the fifth regiment of a four-regiment division, it soon found itself relegated to the sidelines and stuck with all the odd jobs such as providing military police details, couriers, and guards. Correctly reasoning that a larger unit would not be so easily pigeonholed, General Barnett [the Marine Corps Commandant] in October 1917 augmented the Fifth Regiment with the newly formed Sixth Regiment and Sixth Machinegun Battalion. The whole force constituted the AEF Fourth Brigade, or half the infantry of the AEF 2nd Division.*

Although the organization of the Fourth Brigade’s infantry regiments was supposed to be the same as that of all the other AEF infantry regiments, it did in fact differ in some details (see Appendix 2.6). Every Marine rifle and machinegun company had two additional sergeants to serve as gas NCOs and the Marines added gas officers to each battalion headquarters. Whether this helped reduce the number of gas casualties is unclear.

Marine enlisted men also tended to be given higher ranks than their Army counterparts. In a Marine regiment a platoon sergeant was not just the senior sergeant in a platoon, he was a gunnery sergeant, ranking as an Army sergeant first class (a rank that the Army awarded only to specialists) and well above a sergeant. Sergeants commanded all four sections in a Marine rifle platoon and this allowed an additional sergeant per half-platoon. The rifle section included two men trained equipped as snipers (enough for one sniper per half-platoon). Two more snipers were in company headquarters. Since 1887 when test results had exposed their poor marksmanship, the Marines had made rifle shooting into even more of a fetish than it had been in the Army. In contrast to the many soldiers sent into battle without even having fired their rifles, no Marine was even allowed overseas if he had not qualified as an expert rifleman or sharpshooter.

To give extra promotion, pay, and recognition (but not leadership responsibility) to the best shots the Marines introduced the rank of corporal (technical). The rank was also given to mechanics, horseshoers, saddlers, teamsters, and five senior operators in the telephone section of the regimental signal platoon to reward technical proficiency. However, despite their important but difficult and thankless duties, Marine cooks only ranked as privates.

[…]

The Marine AEF regiments differed from their Army counterparts in more than just structural details. They had a huge advantage in manpower quality. Except for about 7,100 draftees accepted during the war’s last weeks, the nearly 79,000 Marines who served in the war were all volunteers. About one sixth of these men had joined prior to the war. This was several times the Army’s percentage of pre-war men, even if those who had only National Guard service are included. Many Marine wartime volunteers were college men and included a lot of athletes.

The large number of officer-quality enlisted men persuaded General Barnett to direct on 4 June 1917 that, in future, all officers be appointed from the ranks. This move had the strong backing of Secretary Daniels who favored the practice of commissioning enlisted men. Such a system would be more in line with what the Germans and French were doing. Even the college men would have to have several months’ enlisted service before they could hope for a commission. By then their leadership potential could be properly evaluated. In addition, many pre-war enlisted men of greater age and experience but less education and growth potential could also become officers. Better still, the Marines were mostly infantry. Unlike the Army, they had few service or technical positions into which their best and brightest could be drained. Instead of getting the dregs, Marine infantry regiments got all the best officers and men. They were always kept at full strength with fully trained replacements, despite heavy casualties.**

The high quality men that the Marines were able to contribute to the AEF provoked a good deal of jealousy within the Army in general and from General Pershing in particular. The latter praised the Marines in private but refused to do so in public. Although Pershing had accepted the Fourth Marine Brigade into the AEF, he rebuffed every offer to send Marine artillery to France. The presence of both Marine infantry and artillery in France would have paved the way for the formation of a Marine AEF division. That would have given the Marines much more publicity at Army expense.

Late in the war Pershing relented enough to accept another Marine infantry brigade, the Fifth, which reached France in September 1918. However, although nearly all these Marines had qualified as expert marksmen, he employed them in menial jobs in the rear areas. At the same time, Pershing was rushing thousands of untrained Army recruits into front line combat where they were routinely and needlessly slaughtered.***

* Major David N. Buckner USMC, A Brief History of the Tenth Marines (Washington DC, Historical Div. HQMC; 1981) pp. 16-17.

** Heinl pp. 191-228; and J. Robert Moskin, The Story of the U.S. Marine Corps (New York, Paddington Press Ltd. 1979) pp. 138-139; LtGen William K. Jones USMC(Ret) A Brief History of the 6th Marines (Washington DC, History and Museum Div. HQMC 1987) p 1.

*** Heinl pp. 194-195 and 208-210; Allan R. Millett, Bullard op cit p. 321.