The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published 27 Aug 2024Douglas MacArthur has a plan for an amphibious invasion of Incheon, and he thinks it will turn the tide of the war. This week comes his heavy pitch to be allowed to do it to the powers-that-be among American command. The war in the field continues as the UN forces win the Battle of the Bowling Alley, but an air force attack accidentally hits targets over the border in China. Mao Zedong is furious. Also, MacArthur gets flak this week from the President for outspokenly advocating actions counter to US official policy with regard to China, so the Chinese situation grows ever more tense.

Chapters

01:28 Battle of the Bowling Alley

04:14 U.N. Air Power

06:46 Supply Issues

09:05 The British are coming

10:55 Incheon Plans

14:52 The Incheon Meeting

17:06 MacArthur and the VFW

20:25 KPA Plans for Next Week

21:24 Summary

(more…)

August 28, 2024

The Korean War Week 010 – MacArthur and the Incheon Meeting – August 27, 1950

August 21, 2024

The Korean War Week 009 – Bloody UN Victory at Naktong Bulge – August 20, 1950

The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published 20 Aug 2024The Marines are deployed to back up the UN forces facing disaster in the Naktong Bulge and by the end of the week the tide has turned, and the crack North Korean 4th Division has been shattered. There is also fighting around the whole rest of the Pusan Perimeter, and it is shrinking from all the attacks, though on the east coast the battle goes in favor of the South Korean forces this week at Pohang-Dong.

(more…)

August 17, 2024

“The notion of a pre-existing Palestinian state is a modern fabrication that ignores the region’s actual history”

Debunking some of the common talking points about the Arab-Israeli conflicts down to the present day:

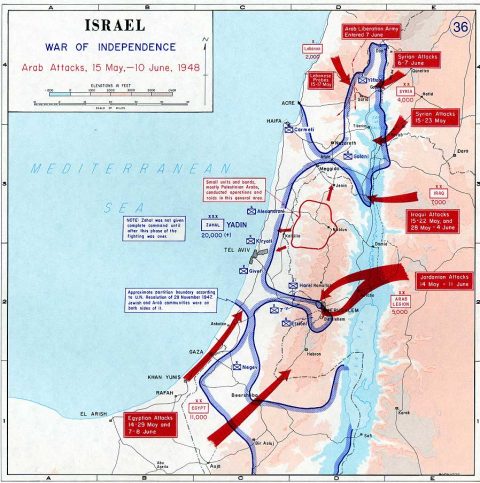

Arab attacks in May and June 1948.

United States Military Academy Atlas, Link.

Before Israel declared independence in 1948, the region now known as Israel, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip was part of the British Mandate for Palestine, which was established by the League of Nations after the fall of the Ottoman Empire in the First World War.

Under Ottoman rule, the area was divided into various administrative districts, with no distinct political entity known as “Palestine”. The concept of a Palestinian national identity emerged in the 20th century, largely in response to the Zionist movement and increased Jewish immigration in the area.

However, there was never a Palestinian state, flag or anthem. The notion of a pre-existing Palestinian state is a modern fabrication that ignores the region’s actual history.

The modern State of Israel’s legitimacy is rooted in international law and global recognition. On Nov. 29, 1947, the United Nations General Assembly passed Resolution 181, known as the “Partition Plan”, proposing two states — one Jewish and one Arab.

The Jewish community accepted the plan, demonstrating a willingness to compromise for peace. However, the Arab states rejected it, refusing to recognize any Jewish state, and instead launched a military assault on Israel following its declaration of independence on May 14, 1948.

Another pervasive myth is the “Nakba” or “catastrophe”, narrative, which claims that Palestinians were forcibly expelled by Israel in 1948. This version omits the critical context that it was the Arab nations that invaded Israel, causing many Arabs to be expelled or flee their homes.

Rather than absorbing the displaced population, the surrounding Arab countries kept them in refugee camps, using them as pawns to pressure Israel. Organizations like UNRWA perpetuated this situation, keeping Palestinians in limbo rather than encouraging their integration into their host countries. This contrasts sharply with how other refugee populations have been handled, where integration and resettlement are the norm.

The land referred to as “Palestine” has always been inherently Jewish. The Jewish people have maintained a continuous presence there for thousands of years, long before Islam or the Arab conquests.

August 14, 2024

The Korean War Week 008 – The First UN Counterattack – August 13, 1950

The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published 13 Aug 2024The first UN large scale counterattack goes off this week; this by the American Task Force Kean. It has both successes and failures, and it runs right into a new North Korean offensive. The fighting happens just about everywhere on the Pusan Perimeter this week, though. That’s the area into which the UN forces have been compressed, and it is particularly threatening at the Naktong Bulge. It is, plain and simple, a week of desperate and bloody fighting and that’s about it.

Chapters

00:47 Recap

01:27 The Pusan Perimeter

04:31 Task Force Kean

07:44 The Naktong Bulge

10:09 The Fight Around Daegu

13:45 Summary

(more…)

August 8, 2024

The Korean War Week 007 – The Pusan Perimeter – August 6, 1950

The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published Aug 6, 2024The UN forces are withdrawn this week across the Naktong River into a new defensive zone in the Southeast corner of the Peninsula — the Pusan Perimeter, but already as the week begins they are in great danger from the right hook near the coast by the North Korean 6th Division, that threatens to upend everything, taking Chinju and aiming for Masan. There are also machinations afoot with the Chinese in Taiwan, and the fear that a larger war could erupt if things aren’t handled right concerning the Chinese; it’s a week full of tension.

(more…)

July 31, 2024

The Korean War Week 006 – Stand or Die! – July 30, 1950

The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published 30 Jul 2024The UN Forces have been pushed back ever further, but this week, US 8th Army Commander Walton Walker issues the order to “stand or die”; he sees no other options. American reinforcements are finally getting into the actual fight, though, and Britain has decided they will send in ground troops, so things might turn around … if they can hold out long enough for those troops to arrive, because a brilliant North Korean strategy might win the war and soon.

(more…)

July 21, 2024

The Atomic Age Begins! – WW2 – Week 308 – July 20, 1945

World War Two

Published 20 Jul 2024This week the Americans explode a nuclear bomb at the Trinity Test in New Mexico. The plan is to possibly use more such bombs against targets in Japan. US President Harry Truman is meanwhile in Germany for the Potsdam Conference with other Allied leaders to hammer out some details of the postwar global order. The active war continues, of course, in Burma, Borneo, the Philippines, and China, with the Japanese being defeated everywhere.

00:00 Intro

00:22 Recap

00:51 The Trinity Test

02:46 The Potsdam Conference Begins

04:09 Bretton Woods Agreement

05:38 The Active War Continues

09:39 Summary

11:00 Conclusion

(more…)

July 17, 2024

Americans Repeatedly Routed – The Korean War – Week 004 – July 16, 1950

The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published 16 Jul 2024Elements of the US 24th Division, the only American one that’s arrived in force in Korea so far, take on the North Korean forces aiming for Taejon, but they are badly — and easily — defeated each time. In the center and the east coast it’s the ROK- the forces of the South — that are reorganizing and getting into position to try to stop the enemy. And Douglas MacArthur is officially appointed commander of all UN forces in Korea.

(more…)

July 15, 2024

Revisiting the “official” story of Srebrenica

Niccolo Soldo’s weekly roundup includes a look at the differences between the story the media told us about the Srebrenica massacre and what has come to light since then:

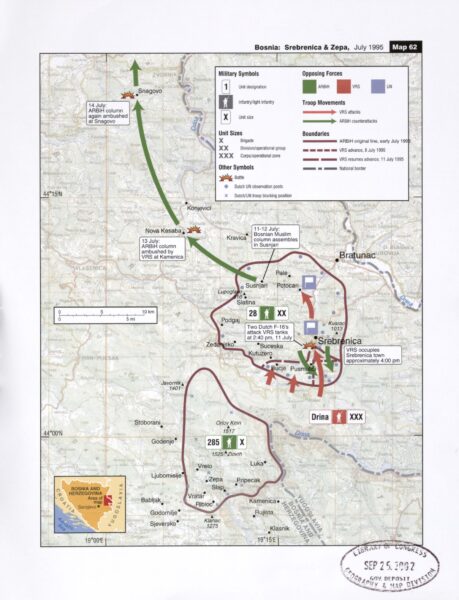

Map of military operations on July, 1995 against the town of Srebrenica.

Map 61 from Balkan Battlegrounds: A Military History of the Yugoslav Conflict; Map Case (2002) via Wikimedia Commons.

29 years ago this week, Bosnian Serb forces of the VRS managed to seize the town of Srebrenica in Eastern Bosnia, on the border with Serbia. A massacre of Bosnian Muslim males ensued shortly thereafter, and the narrative of genocide sprung forth quickly from it, giving cause to NATO’s intervention in that conflict.

Did a massacre occur? Certainly. Some 2,000 Bosnian Muslim males were summarily executed by Bosnian Serb forces around Srebrenica shortly after the UN-designated “safe haven” fell to the Serbs. Some 8,000 Bosnian Muslims lost their lives in the immediate aftermath of the fall of Srebrenica, but the narrative of “genocide” whereby all 8,000 were executed is simply not true as per John Schindler, the then-Technical Director for the Balkans Division of the NSA:

Twenty-nine years ago today, the Bosnian Serb Army captured Srebrenica, an isolated town in Bosnia’s east that was jam-packed with Bosnian Muslims, most of them refugees. This small offensive, involving only a couple of battalions of Bosnian Serb troops, soon became the biggest story in the world. What happened around Srebrenica in mid-July 1995 permanently changed the West’s approach to war-making and diplomacy.

The essential facts of the Srebrenica massacre are not in dispute. The town was a United Nations “safe area” but U.N. peacekeepers there, an understrength Dutch battalion, failed to protect anyone. Over the week following Srebrenica’s quick fall, some 8,000 Bosnian Muslims, almost all male, a mix of civilians and military personnel, were killed by Bosnian Serb forces. About 2,000 disarmed Bosnian Muslim prisoners of war were executed soon after the town’s capture. The rest died in the days that followed, all over eastern Bosnia.

As the world learned the extent of the massacre, by far the biggest atrocity in the Bosnian War that had raged since the spring of 1992, Western anger mounted. Six weeks later, President Bill Clinton ordered the Pentagon to bomb the Bosnian Serbs in Operation Deliberate Force, the first major military action in NATO’s history. By the year’s end, the war was concluded by American-led diplomacy.

Here are Schindler’s conclusions:

That for three years, Srebrenica, supposedly a U.N. “safe area,” served as a staging base for Bosnian Muslim attacks into Serb territory. The Muslim military’s 28th Division regularly attacked out of Srebrenica. Bosnian Serbs claim they lost over 3,000 people, civilian and military, to those attacks.

That the Bosnian Muslim commander at Srebrenica, Naser Oric, was a thug who tortured and killed Serb civilians (he showed Western journalists footage of his troops decapitating Serb prisoners), as well as fellow Muslims he disliked. Mysteriously, Oric fled Srebrenica three months before the town’s fall, leaving his troops to die.

That most of the Bosnian Muslim dead, some three-quarters of them, died not at Srebrenica but during an attempted breakout by troops of the 28th Division to reach their own lines around Tuzla. They showed little communications discipline, and Bosnian Serb forces called down their artillery on them, columns of Muslim military and civilians together, slaughtering them. This doesn’t meet any standard definition of genocide.

That the Muslims were flying weapons into the “safe area” by helicopter in the months before the Bosnian Serb offensive. (Controversially, the Pentagon knew this was happening but pretended it didn’t.) The Serbs repeatedly protested to the U.N. about this violation, to no avail. This was the reason for the offensive to take the town.

There’s also convincing evidence that the Muslim leadership in Sarajevo knew Srebrenica would be attacked and allowed it to fall. Their leader, Alija Izetbegovic, stated that if Srebrenica fell, the Serbs would massacre Muslims as payback, and America would intervene on the Muslim side in the war. He was right.

Some of you may not like what John has to say here about Gaza and how it relates to Srebrenica:

This isn’t merely a historical matter. What happened in Bosnia is being repeated today in Gaza. Western journalists uncritically accept Muslim claims about war crimes and “genocide” to smear a Western state that’s at war with radical Islam.

Here the strange ideological affinity between jihadists and the Western Left plays a role, as it did during the Bosnian War as well. No claims of war crimes, which possess great political value on the world stage, should be accepted without independent confirmation. Srebrenica should have taught Western elites this essential truth, but it didn’t.

On a personal note, I like to bring up Srebrenica to Serbs as an example of how media shapes narratives that are often very remote from the truth in the hope that they understand what I am saying in a wider context.

Fun fact: Srebrenica translates into “Silverton”, as it was a significant silver mining town during the late Medieval era, with imported Saxons running the show.

July 3, 2024

The Korean War Week 002 – The Fall of Seoul – July 2, 1950

The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published 2 Jul 2024The North Korean forces are advancing all over, and this week they take Seoul, the South’s capital city, after just a few days of the war. There is another tragedy for the South when the Han River Bridge is blown while thousands of people are crossing it, resulting in hundreds of civilian deaths. The world responds to the invasion — condemning it everywhere, and the Americans decide to send in ground forces to help the South.

(more…)

June 26, 2024

The Korean War Begins – Week 1 – June 25, 1950

The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published 25 Jun 2024Despite the fact that there have been clear signs that they might soon invade South Korea, when the North actually does in force on June 25th, 1950, it comes as a complete shock to the world. But is this a full invasion, or just cross border raids such as there were in 1949? And is there something more behind this? Stalin’s Soviets? Mao’s Chinese? And how will the world react? Find out this week as our week by week coverage of the war begins!

(more…)

June 14, 2024

When propaganda wins over historical facts, Ontario public schools edition

To someone of my generation (late boomer/early GenX), the history of the Residential School system was taught, at least superficially, in middle school. Along with the early settlement of what is now Canada by the French and later the English (with a very brief nod to the Vikings, of course), we got a cursory introduction to the relationships among the European settlers and explorers and the various First Nations groups they encountered. It wasn’t in great depth — what is taught in great depth in middle school? — but we got a rough outline. In my case, details about the Residential School system came more from a “young adult” novel about a young First Nations student running away from his school and trying to find his way back to his home and family. My best friend in school had First Nations ancestry, so I felt a strong desire to understand the book and the system and culture portrayed in it.

Kamloops Indian Residential School, 1930.

Photo from Archives Deschâtelets-NDC, Richelieu via Wikimedia Commons.

If, in the early 1970s, the Ontario school system taught at least a bit about the history of the First Nations peoples, how is it possible that they stopped doing so and my son’s generation were utterly blindsided by the sensationalist treatment of the students at a particular Residential School in British Columbia? And as a result, were far more credulous and willing to believe the worst that the “anticolonialist” propagandists could come up with.

“Igor Stravinsky” is a teacher in the Ontario school system who writes under a pseudonym for fairly obvious reasons, as he’s not a believer in the modern narrative about the history of First Nations children in the Residential School system:

This will be my last instalment of this series. I have attempted to shed light on the poor quality of information students are receiving in Ontario schools with regard to Indigenous history and current issues. It is important to note that this is being done intentionally. It is to the advantage of the leaders of the Indigenous Grievance Industry to characterise Canada and the pre-Canadian colonies of this land as genocidal oppressors, and our politicians have exploited this situation for crass political gain. This was perhaps epitomised by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s photo op of himself holding a teddy bear in the proximity of a soil disturbance in a field at the site of a former residential school in Cowessess First Nation, Saskatchewan on Tuesday, July 6, 2021:

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau holding a teddy bear in Cowessess First Nation, Saskatchewan.

July 6, 2021.Are there actually human remains there? If so, of whom? Is this evidence of any kind of foul play? These are questions he was not about to bother to ask. Why would he, when such a golden opportunity to score political points presented itself?

We now know all this murdered Indigenous children stuff was a big hoax but don’t hold your breath waiting for Trudeau to issue an apology for staining the international reputation of Canada and triggering a knee-jerk vote by our Parliament declaring Canada a genocidal state and adopting the The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (more on that below). Undoing all this damage will be a herculean task.

Just as students are fed simplistic, misleading, and false information about the past with regard to Indigenous people (the focus being the Indian Residential Schools) they are being presented with the point of view that human rights violations against the Indigenous people are ongoing, and are the reason for the poor quality of life in which such a disproportionate number of Indigenous people find themselves.

The claim of generational trauma

On Apr. 27, 2010, speaking as chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and for the people of Canada, Sinclair told the Ninth Session of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues: “For roughly seven generations nearly every Indigenous child in Canada was sent to a residential school. They were taken from their families, tribes and communities, and forced to live in those institutions of assimilation.”

This lie is promoted in the schools. It is the foundation of the generational trauma claim but in fact, during the IRS era, perhaps 30% of Status Indians (you can cut that figure in half if you include all people who identify as Indigenous) ever attended, and for an average of 4.5 years.

Even if it were true that most Indigenous people who attended the IRS suffered trauma, there is no evidence or logical reason to believe that trauma could be transferred down the generations. If generational trauma is a thing, why have the descendants of the victims of the holocaust been doing so well?

If there is generational trauma, the culprit is alcohol. Alcohol abuse has been a major problem in Indigenous communities since first contact but rarely comes up these days, certainly not in schools. Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS), which occurs when a mother consumes alcohol during pregnancy, is also a major problem and the children born with it suffer from mental and emotional challenges throughout their lives. It impacts their social life, education and work. Girls who suffer from the condition all too often end up drinking during pregnancy themselves and the cycle continues.

February 28, 2024

Accusations aplenty, but still no clear evidence

Michelle Stirling outlines the establishment of the North West Mounted Police (today’s Royal Canadian Mounted Police) and their role in driving out American whiskey traders and criminal gangs who had invaded the Canadian west, and the initial role of Sir John A. Macdonald in setting up the first residential schools for First Nations children:

Kamloops Indian Residential School, 1930.

Photo from Archives Deschâtelets-NDC, Richelieu via Wikimedia Commons.

It is clear that the claim of “mass graves” of children allegedly found by Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School is false. The main reason is that there is no list of names of missing persons — over the course of 113 years of Indian Residential Schools, which saw 150,000 students go through the system, some staying for a year, most for an average of 4.5 years, some staying for a decade or more and graduating, and some orphans being taken in to the school as children, then remaining to work as Indigenous staff — these many thousands of children passed through Indian Residential Schools, their parents enrolling and re-enrolling them year after year.

And there is no list of names of missing persons.

There are many claims of missing persons.

Some of these claims are quite fatuous — with one person claiming that in their Band, every family had four or five children who went missing at that school. Another person claimed that their grandfather had ten siblings disappear in that school.

If that were true, the Band would have ceased to exist.

Despite these claims, there are no missing persons records.

And every student who went to that school is documented on the Band’s Treaty rolls, in documents of the Indian Agent, in the enrollment forms at the Department of Indian Affairs, along with the student’s medical certificate for entry, and in the quarterly reports of the department.

In fact, the Indigenous population of Canada grew from about 102,358 in 1871 to now 1.8 million.

It seems that the claim of a “mass grave” on the former Kamloops Indian Residential School site was timed to “nudge” the approval of the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous People through parliament — which it did! The bill had been “stuck” as six provinces had requested delay and clarity on key issues. Once the claim of “mass graves” surfaced — boom!

Less than a month after the “mass graves” news shot round the world, shocking the global community that Canadians — once known as international peacemakers, were actually hideous murderers of Indigenous children — UNDRIP swept through the Canadian Parliament with no objection.

A day later, China accused Canada of genocide, citing the Kamloops “mass graves” find as proof. For those of you following the concerns about China’s alleged interference in elections in Canada, this rather convenient timing might set off some alarm bells.

If anything, the RCMP should be investigating this matter on grounds of false pretences or fraud. But the RCMP appear to have transferred the investigation of the Kamloops “mass grave” to the people who claimed to have found them! Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) can only identify “disturbances” under ground, not bodies or coffins. In fact, based on previous land use records, most likely the GPR found 215 clay tiles of an old septic trench.

February 12, 2024

Yalta, When Stalin Split the World – a WW2 Special

World War Two

Published 11 February 2024Indy and Sparty take you through the negotiations at Yalta as The Big Three thrash out the shape of the postwar world. As the splits between East and West continue to deepen, who will come out on top?

(more…)

January 23, 2024

The Korean War: The First Year

Army University Press

Published Jan 22, 2024Created for the Department of Command and Leadership and the Department of Military History at the US Army Command and General Staff College, The Korean War: The First Year is a short documentary focused on the major events of the Forgotten War. Designed to address the complex strategic and operational actions from June 1950 – June 1951, the film answers seven key questions that can be found in the timestamps below. Major events such as the initial North Korean invasion, the defense of the Pusan Perimeter, the Inchon landing, and the Chinese intervention are discussed.

Timestamps:

1. Why are there Two Koreas? – 00:25

2. Why did North Korea Attack South Korea? – 02:39

3. How did the UN stop the Communist invasion? – 06:30

4. Why did MacArthur attack at Inchon? – 10:24

5. Why did the UN attack into North Korea? – 14:27

6. Why did China enter the Korean War? – 18:51

7. How did the UN stop the Communist invasion … again? – 21:44