New York just killed every economist’s favorite thing about Uber: surge pricing. Sure, many economists also love convenient car service at the touch of a button. But black-car services have been around for a long time. Explicit surge pricing — which both creates new supply and rations demand — has not, but it’s long been a core feature of Uber Technologies Inc.’s business model. While it can be annoying at times (during a recent rainstorm, I noticed a sudden epidemic of drivers canceling rides, which I suspect was due to the rapidly rising surge price), it also allows you to be sure that you will be able to get a taxi on New Year’s Eve or during a rainstorm as long as you’re willing to pay extra.

Sadly, no one else loves surge pricing as much as economists do. Instead of getting all excited about the subtle, elegant machinery of price discovery, people get all outraged about “price gouging.” No matter how earnestly economists and their fellow travelers explain that this is irrational madness — that price gouging actually makes everyone better off by ensuring greater supply and allocating the supply to (approximately) those with the greatest demand — the rest of the country continues to view marking up generators after a hurricane, or similar maneuvers, as a pretty serious moral crime.

Megan McArdle, “Uber Makes Economists Sad”, Bloomberg View, 2014-07-09.

June 24, 2015

QotD: Surge pricing

May 21, 2015

Jonathan Kay, ebike martyr

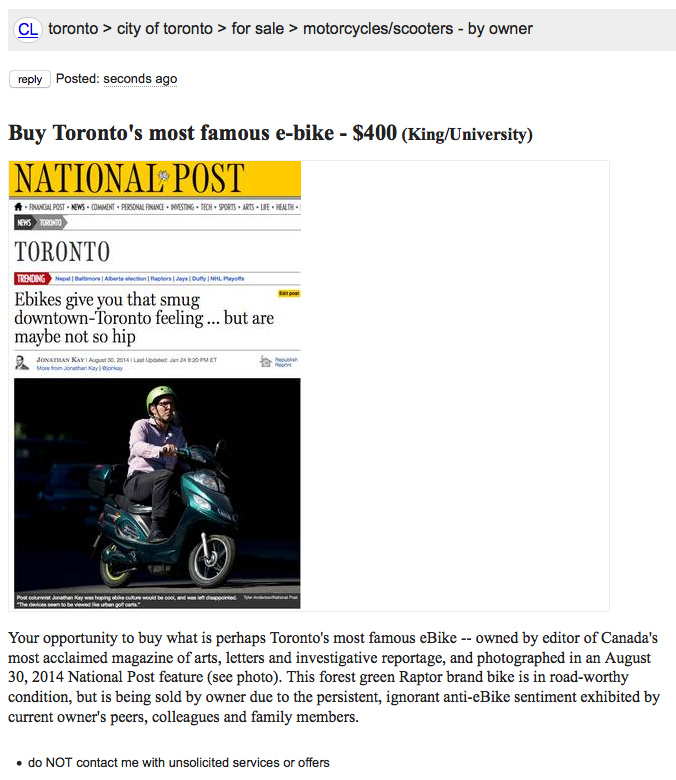

Despite having become the editor-in-chief of The Walrus, poor Jonathan Kay suffers the slings and arrows of all those who condemn and ridicule his ridiculous choice of transportation ebike (especially from his own staff):

City planners think of transportation in terms of its logistical and infrastructural components. That’s also how the issue gets discussed in the context of, say, energy conservation and traffic management. But when it comes to the transportation products we actually buy, our utilitarian calculus is overwhelmed by our aesthetic biases. When the Segway scooter had its great reveal in 2001, few observers cared about its groundbreaking self-balancing technology. All they saw was a nerd standing upright, wearing a funny helmet.

It is a lesson I have learned again over the last year, at great cost in dignity and personal reputation, as I have motored around Toronto on an ebike — a zero-emission electric scooter that travels at speeds of up to 32 km/h. As I noted in an essay last year, ebikes combine the low cost and convenience of a bicycle, while allowing a user to get to work without an ounce of sweat or a stitch of lycra.

In a more perfect world, the streets of our cities would be humming with ebikes. But that is not the world we inhabit. After a year of evangelizing these fantastically useful, earth-friendly contraptions among my peer group, I’ve failed to gain a single new convert.

Just the opposite, in fact: I have become a figure of overt and willfully cruel mockery.

May 10, 2015

QotD: The German love of order

In Germany one breathes in love of order with the air, in Germany the babies beat time with their rattles, and the German bird has come to prefer the box, and to regard with contempt the few uncivilised outcasts who continue to build their nests in trees and hedges. In course of time every German bird, one is confident, will have his proper place in a full chorus. This promiscuous and desultory warbling of his must, one feels, be irritating to the precise German mind; there is no method in it. The music-loving German will organise him. Some stout bird with a specially well-developed crop will be trained to conduct him, and, instead of wasting himself in a wood at four o’clock in the morning, he will, at the advertised time, sing in a beer garden, accompanied by a piano. Things are drifting that way.

Your German likes nature, but his idea of nature is a glorified Welsh Harp. He takes great interest in his garden. He plants seven rose trees on the north side and seven on the south, and if they do not grow up all the same size and shape it worries him so that he cannot sleep of nights. Every flower he ties to a stick. This interferes with his view of the flower, but he has the satisfaction of knowing it is there, and that it is behaving itself. The lake is lined with zinc, and once a week he takes it up, carries it into the kitchen, and scours it. In the geometrical centre of the grass plot, which is sometimes as large as a tablecloth and is generally railed round, he places a china dog. The Germans are very fond of dogs, but as a rule they prefer them of china. The china dog never digs holes in the lawn to bury bones, and never scatters a flower-bed to the winds with his hind legs. From the German point of view, he is the ideal dog. He stops where you put him, and he is never where you do not want him. You can have him perfect in all points, according to the latest requirements of the Kennel Club; or you can indulge your own fancy and have something unique. You are not, as with other dogs, limited to breed. In china, you can have a blue dog or a pink dog. For a little extra, you can have a double-headed dog.

On a certain fixed date in the autumn the German stakes his flowers and bushes to the earth, and covers them with Chinese matting; and on a certain fixed date in the spring he uncovers them, and stands them up again. If it happens to be an exceptionally fine autumn, or an exceptionally late spring, so much the worse for the unfortunate vegetable. No true German would allow his arrangements to be interfered with by so unruly a thing as the solar system. Unable to regulate the weather, he ignores it.

Among trees, your German’s favourite is the poplar. Other disorderly nations may sing the charms of the rugged oak, the spreading chestnut, or the waving elm. To the German all such, with their wilful, untidy ways, are eyesores. The poplar grows where it is planted, and how it is planted. It has no improper rugged ideas of its own. It does not want to wave or to spread itself. It just grows straight and upright as a German tree should grow; and so gradually the German is rooting out all other trees, and replacing them with poplars.

Your German likes the country, but he prefers it as the lady thought she would the noble savage — more dressed. He likes his walk through the wood — to a restaurant. But the pathway must not be too steep, it must have a brick gutter running down one side of it to drain it, and every twenty yards or so it must have its seat on which he can rest and mop his brow; for your German would no more think of sitting on the grass than would an English bishop dream of rolling down One Tree Hill. He likes his view from the summit of the hill, but he likes to find there a stone tablet telling him what to look at, find a table and bench at which he can sit to partake of the frugal beer and “belegte Semmel” he has been careful to bring with him. If, in addition, he can find a police notice posted on a tree, forbidding him to do something or other, that gives him an extra sense of comfort and security.

Jerome K. Jerome, Three Men on the Bummel, 1914.

March 29, 2015

QotD: Writing about scenery

Lastly, in this book there will be no scenery. This is not laziness on my part; it is self-control. Nothing is easier to write than scenery; nothing more difficult and unnecessary to read. When Gibbon had to trust to travellers’ tales for a description of the Hellespont, and the Rhine was chiefly familiar to English students through the medium of Caesar’s Commentaries, it behooved every globe-trotter, for whatever distance, to describe to the best of his ability the things that he had seen. Dr. Johnson, familiar with little else than the view down Fleet Street, could read the description of a Yorkshire moor with pleasure and with profit. To a cockney who had never seen higher ground than the Hog’s Back in Surrey, an account of Snowdon must have appeared exciting. But we, or rather the steam-engine and the camera for us, have changed all that. The man who plays tennis every year at the foot of the Matterhorn, and billiards on the summit of the Rigi, does not thank you for an elaborate and painstaking description of the Grampian Hills. To the average man, who has seen a dozen oil paintings, a hundred photographs, a thousand pictures in the illustrated journals, and a couple of panoramas of Niagara, the word-painting of a waterfall is tedious.

An American friend of mine, a cultured gentleman, who loved poetry well enough for its own sake, told me that he had obtained a more correct and more satisfying idea of the Lake district from an eighteenpenny book of photographic views than from all the works of Coleridge, Southey, and Wordsworth put together. I also remember his saying concerning this subject of scenery in literature, that he would thank an author as much for writing an eloquent description of what he had just had for dinner. But this was in reference to another argument; namely, the proper province of each art. My friend maintained that just as canvas and colour were the wrong mediums for story telling, so word-painting was, at its best, but a clumsy method of conveying impressions that could much better be received through the eye.

Jerome K. Jerome, Three Men on the Bummel, 1914.

March 22, 2015

QotD: Conveying useful information

I wish to be equally frank with the reader of this book. I wish here conscientiously to let forth its shortcomings. I wish no one to read this book under a misapprehension.

There will be no useful information in this book.

Anyone who should think that with the aid of this book he would be able to make a tour through Germany and the Black Forest would probably lose himself before he got to the Nore. That, at all events, would be the best thing that could happen to him. The farther away from home he got, the greater only would be his difficulties.

I do not regard the conveyance of useful information as my forte. This belief was not inborn with me; it has been driven home upon me by experience.

In my early journalistic days, I served upon a paper, the forerunner of many very popular periodicals of the present day. Our boast was that we combined instruction with amusement; as to what should be regarded as affording amusement and what instruction, the reader judged for himself. We gave advice to people about to marry — long, earnest advice that would, had they followed it, have made our circle of readers the envy of the whole married world. We told our subscribers how to make fortunes by keeping rabbits, giving facts and figures. The thing that must have surprised them was that we ourselves did not give up journalism and start rabbit-farming. Often and often have I proved conclusively from authoritative sources how a man starting a rabbit farm with twelve selected rabbits and a little judgment must, at the end of three years, be in receipt of an income of two thousand a year, rising rapidly; he simply could not help himself. He might not want the money. He might not know what to do with it when he had it. But there it was for him. I have never met a rabbit farmer myself worth two thousand a year, though I have known many start with the twelve necessary, assorted rabbits. Something has always gone wrong somewhere; maybe the continued atmosphere of a rabbit farm saps the judgment.

We told our readers how many bald-headed men there were in Iceland, and for all we knew our figures may have been correct; how many red herrings placed tail to mouth it would take to reach from London to Rome, which must have been useful to anyone desirous of laying down a line of red herrings from London to Rome, enabling him to order in the right quantity at the beginning; how many words the average woman spoke in a day; and other such like items of information calculated to make them wise and great beyond the readers of other journals.

Jerome K. Jerome, Three Men on the Bummel, 1914.

February 1, 2015

QotD: Travellers’ phrase books

[George] handed me a small book bound in red cloth. It was a guide to English conversation for the use of German travellers. It commenced “On a Steam-boat,” and terminated “At the Doctor’s”; its longest chapter being devoted to conversation in a railway carriage, among, apparently, a compartment load of quarrelsome and ill-mannered lunatics: “Can you not get further away from me, sir?” — “It is impossible, madam; my neighbour, here, is very stout” — “Shall we not endeavour to arrange our legs?” — “Please have the goodness to keep your elbows down” — “Pray do not inconvenience yourself, madam, if my shoulder is of any accommodation to you,” whether intended to be said sarcastically or not, there was nothing to indicate — “I really must request you to move a little, madam, I can hardly breathe,” the author’s idea being, presumably, that by this time the whole party was mixed up together on the floor. The chapter concluded with the phrase, “Here we are at our destination, God be thanked! (Gott sei dank!)” a pious exclamation, which under the circumstances must have taken the form of a chorus.

At the end of the book was an appendix, giving the German traveller hints concerning the preservation of his health and comfort during his sojourn in English towns, chief among such hints being advice to him to always travel with a supply of disinfectant powder, to always lock his bedroom door at night, and to always carefully count his small change.

“It is not a brilliant publication,” I remarked, handing the book back to George; “it is not a book that personally I would recommend to any German about to visit England; I think it would get him disliked. But I have read books published in London for the use of English travellers abroad every whit as foolish. Some educated idiot, misunderstanding seven languages, would appear to go about writing these books for the misinformation and false guidance of modern Europe.”

“You cannot deny,” said George, “that these books are in large request. They are bought by the thousand, I know. In every town in Europe there must be people going about talking this sort of thing.”

“Maybe,” I replied; “but fortunately nobody understands them. I have noticed, myself, men standing on railway platforms and at street corners reading aloud from such books. Nobody knows what language they are speaking; nobody has the slightest knowledge of what they are saying. This is, perhaps, as well; were they understood they would probably be assaulted.”

George said: “Maybe you are right; my idea is to see what would happen if they were understood. My proposal is to get to London early on Wednesday morning, and spend an hour or two going about and shopping with the aid of this book. There are one or two little things I want — a hat and a pair of bedroom slippers, among other articles. Our boat does not leave Tilbury till twelve, and that just gives us time. I want to try this sort of talk where I can properly judge of its effect. I want to see how the foreigner feels when he is talked to in this way.”

It struck me as a sporting idea. In my enthusiasm I offered to accompany him, and wait outside the shop. I said I thought that Harris would like to be in it, too — or rather outside.

George said that was not quite his scheme. His proposal was that Harris and I should accompany him into the shop. With Harris, who looks formidable, to support him, and myself at the door to call the police if necessary, he said he was willing to adventure the thing.

We walked round to Harris’s, and put the proposal before him. He examined the book, especially the chapters dealing with the purchase of shoes and hats. He said:

“If George talks to any bootmaker or any hatter the things that are put down here, it is not support he will want; it is carrying to the hospital that he will need.”

That made George angry.

“You talk,” said George, “as though I were a foolhardy boy without any sense. I shall select from the more polite and less irritating speeches; the grosser insults I shall avoid.”

This being clearly understood, Harris gave in his adhesion; and our start was fixed for early Wednesday morning.

Jerome K. Jerome, Three Men on the Bummel, 1914.

January 23, 2015

QotD: Taxicab cartels

Around the world, the government-charted monopolies and cartels that run the taxi business responded with protests and violence to the emergence of technology-empowered competitors such as Uber, which does not undercut traditional taxis on cost — in New York, its drivers earn about three times what a traditional cabbie makes — but is much more convenient for those who do not live or work in areas that are generally well-served by traditional taxis. As in most cities, New York law imposes price uniformity on taxis and long protected them from most competition, with the entirely predictable result that consumers are the worst-served parties in the taxi business. (It does not help matters that, unlike their London counterparts, famously steeped in “the Knowledge,” the typical New York cabbie cannot find the Brooklyn Bridge without GPS or turn-by-turn instructions from the passenger.) The lack of consumer focus has some perverse consequences here in New York: The taxi fleet schedules its shift change from 4 p.m. to 5 p.m., meaning that taxis all but vanish from the streets during the hours when they are most needed. The New York Times calls this an “apparent violation of the laws of supply and demand,” which, New York Times geniuses, is exactly what happens when you use regulation to take supply and demand effectively out of the equation. A platform that combined Uber’s on-demand service with Google-style driverless cars would probably put the traditional taxi out of business — assuming that the cartels are not able to use government to strangle innovation in its cradle.

Kevin D. Williamson, “Race On, for Driverless Cars: On the beauty of putting the consumer in the driver’s seat”, National Review, 2014-06-01.

January 11, 2015

QotD: Always make a list

The wheel business settled, there arose the ever-lasting luggage question.

“The usual list, I suppose,” said George, preparing to write.

That was wisdom I had taught them; I had learned it myself years ago from my Uncle Podger.

“Always before beginning to pack,” my Uncle would say, “make a list.”

He was a methodical man.

“Take a piece of paper” — he always began at the beginning — “put down on it everything you can possibly require, then go over it and see that it contains nothing you can possibly do without. Imagine yourself in bed; what have you got on? Very well, put it down — together with a change. You get up; what do you do? Wash yourself. What do you wash yourself with? Soap; put down soap. Go on till you have finished. Then take your clothes. Begin at your feet; what do you wear on your feet? Boots, shoes, socks; put them down. Work up till you get to your head. What else do you want besides clothes? A little brandy; put it down. A corkscrew, put it down. Put down everything, then you don’t forget anything.”

That is the plan he always pursued himself. The list made, he would go over it carefully, as he always advised, to see that he had forgotten nothing. Then he would go over it again, and strike out everything it was possible to dispense with.

Then he would lose the list.

Said George: “Just sufficient for a day or two we will take with us on our bikes. The bulk of our luggage we must send on from town to town.”

“We must be careful,” I said; “I knew a man once—”

Harris looked at his watch.

“We’ll hear about him on the boat,” said Harris; “I have got to meet Clara at Waterloo Station in half an hour.”

“It won’t take half an hour,” I said; “it’s a true story, and—”

“Don’t waste it,” said George: “I am told there are rainy evenings in the Black Forest; we may be glad of it. What we have to do now is to finish this list.”

Now I come to think of it, I never did get off that story; something always interrupted it. And it really was true.

Jerome K. Jerome, Three Men on the Bummel, 1914.

January 10, 2015

Sub-orbital airliners? Not if you know much about economics and physics

Charles Stross in full “beat up the optimists” mode over a common SF notion about sub-orbital travel for the masses:

Let’s start with a simple normative assumption; that sub-orbital spaceplanes are going to obey the laws of physics. One consequence of this is that the amount of energy it takes to get from A to B via hypersonic airliner is going to exceed the energy input it takes to cover the same distance using a subsonic jet, by quite a margin. Yes, we can save some fuel by travelling above the atmosphere and cutting air resistance, but it’s not a free lunch: you expend energy getting up to altitude and speed, and the fuel burn for going faster rises nonlinearly with speed. Concorde, flying trans-Atlantic at Mach 2.0, burned about the same amount of fuel as a Boeing 747 of similar vintage flying trans-Atlantic at Mach 0.85 … while carrying less than a quarter as many passengers.

Rockets aren’t a magic technology. Neither are hybrid hypersonic air-breathing gadgets like Reaction Engines‘ Sabre engine. It’s going to be a wee bit expensive. But let’s suppose we can get the price down far enough that a seat in a Mach 5 to Mach 10 hypersonic or sub-orbital passenger aircraft is cost-competitive with a high-end first class seat on a subsonic jet. Surely the super-rich will all switch to hypersonic services in a shot, just as they used Concorde to commute between New York and London back before Airbus killed it off by cancelling support after the 30-year operational milestone?

Well, no.

Firstly, this is the post-9/11 age. Obviously security is a consideration for all civil aviation, right? Well, no: business jets are largely exempt, thanks to lobbying by their operators, backed up by their billionaire owners. But those of us who travel by civil airliners open to the general ticket-buying public are all suspects. If something goes wrong with a scheduled service, fighters are scrambled to intercept it, lest some fruitcake tries to fly it into a skyscraper.

So not only are we not going to get our promised flying cars, we’re not going to get fast, cheap, intercontinental travel options. But what about those hyper-rich folks who spend money like water?

First class air travel by civil aviation is a dying niche today. If you are wealthy enough to afford the £15,000-30,000 ticket cost of a first-class-plus intercontinental seat (or, rather, bedroom with en-suite toilet and shower if we’re talking about the very top end), you can also afford to pay for a seat on a business jet instead. A number of companies operate profitably on the basis that they lease seats on bizjets by the hour: you may end up sharing a jet with someone else who’s paying to fly the same route, but the operating principle is that when you call for it a jet will turn up and take you where you want to go, whenever you want. There’s no security theatre, no fuss, and it takes off when you want it to, not when the daily schedule says it has to. It will probably have internet connectivity via satellite—by the time hypersonic competition turns up, this is not a losing bet—and for extra money, the sky is the limit on comfort.

I don’t get to fly first class, but I’ve watched this happen over the past two decades. Business class is holding its own, and premium economy is growing on intercontinental flights (a cut-down version of Business with more leg-room than regular economy), but the number of first class seats you’ll find on an Air France or British Airways 747 is dwindling. The VIPs are leaving the carriers, driven away by the security annoyances and drawn by the convenience of much smaller jets that come when they call.

For rich people, time is the only thing money can’t buy. A HST flying between fixed hubs along pre-timed flight paths under conditions of high security is not convenient. A bizjet that flies at their beck and call is actually speedier across most intercontinental routes, unless the hypersonic route is serviced by multiple daily flights—which isn’t going to happen unless the operating costs are comparable to a subsonic craft.

January 7, 2015

In praise of the bus, but not “the buses”

Over at The Register, someone accidentally let Simon Rockman get up on his hobby horse and start yelling nasty things about buses:

A bus is a fantastically efficient way to move a large number of people. Buses however are not. They are a dreadful system for getting people to work.

The difference is not as subtle as that sentence may make it seem. What lies behind it is that when you want to move a large number of people from one place to another all at once, a works outing for instance, a Charabanc makes perfect sense.

But it doesn’t scale. If you want to travel by bus there needs to be a regular service. That means lots of buses have to waft up and down a route in anticipation of there being someone who wants to get on. In a major city, and I live in London, that’s good for some of the time. So long as there is a steady supply of people there can be a good number on the bus. This of course doesn’t work very early in the morning or late at night when there are not enough people.

What’s worse is that buses don’t go from where people live to where they work. Unless you live by a bus stop, in which case you have the kinds of people who hang around bus stops hanging around your house, you’ll have to walk to it. The same is true at the other end. Then you have to wait for the bus. If I walk down to my nearest bus stop and a bus arrives as I get there I think it’s a fantastic, special happening. If I walk out of my house and my car is there I think “that’s normal”.

January 4, 2015

QotD: Camping in the rain

Camping out in rainy weather is not pleasant.

It is evening. You are wet through, and there is a good two inches of water in the boat, and all the things are damp. You find a place on the banks that is not quite so puddly as other places you have seen, and you land and lug out the tent, and two of you proceed to fix it.

It is soaked and heavy, and it flops about, and tumbles down on you, and clings round your head and makes you mad. The rain is pouring steadily down all the time. It is difficult enough to fix a tent in dry weather: in wet, the task becomes herculean. Instead of helping you, it seems to you that the other man is simply playing the fool. Just as you get your side beautifully fixed, he gives it a hoist from his end, and spoils it all.

“Here! what are you up to?” you call out.

“What are you up to?” he retorts; “leggo, can’t you?”

“Don’t pull it; you’ve got it all wrong, you stupid ass!” you shout.

“No, I haven’t,” he yells back; “let go your side!”

“I tell you you’ve got it all wrong!” you roar, wishing that you could get at him; and you give your ropes a lug that pulls all his pegs out.

“Ah, the bally idiot!” you hear him mutter to himself; and then comes a savage haul, and away goes your side. You lay down the mallet and start to go round and tell him what you think about the whole business, and, at the same time, he starts round in the same direction to come and explain his views to you. And you follow each other round and round, swearing at one another, until the tent tumbles down in a heap, and leaves you looking at each other across its ruins, when you both indignantly exclaim, in the same breath:

“There you are! what did I tell you?”

Meanwhile the third man, who has been baling out the boat, and who has spilled the water down his sleeve, and has been cursing away to himself steadily for the last ten minutes, wants to know what the thundering blazes you’re playing at, and why the blarmed tent isn’t up yet.

At last, somehow or other, it does get up, and you land the things. It is hopeless attempting to make a wood fire, so you light the methylated spirit stove, and crowd round that.

Rainwater is the chief article of diet at supper. The bread is two-thirds rainwater, the beefsteak-pie is exceedingly rich in it, and the jam, and the butter, and the salt, and the coffee have all combined with it to make soup.

After supper, you find your tobacco is damp, and you cannot smoke. Luckily you have a bottle of the stuff that cheers and inebriates, if taken in proper quantity, and this restores to you sufficient interest in life to induce you to go to bed.

There you dream that an elephant has suddenly sat down on your chest, and that the volcano has exploded and thrown you down to the bottom of the sea — the elephant still sleeping peacefully on your bosom. You wake up and grasp the idea that something terrible really has happened. Your first impression is that the end of the world has come; and then you think that this cannot be, and that it is thieves and murderers, or else fire, and this opinion you express in the usual method. No help comes, however, and all you know is that thousands of people are kicking you, and you are being smothered.

Somebody else seems in trouble, too. You can hear his faint cries coming from underneath your bed. Determining, at all events, to sell your life dearly, you struggle frantically, hitting out right and left with arms and legs, and yelling lustily the while, and at last something gives way, and you find your head in the fresh air. Two feet off, you dimly observe a half-dressed ruffian, waiting to kill you, and you are preparing for a life-and-death struggle with him, when it begins to dawn upon you that it’s Jim.

“Oh, it’s you, is it?” he says, recognising you at the same moment.

“Yes,” you answer, rubbing your eyes; “what’s happened?”

“Bally tent’s blown down, I think,” he says. “Where’s Bill?”

Then you both raise up your voices and shout for “Bill!” and the ground beneath you heaves and rocks, and the muffled voice that you heard before replies from out the ruin:

“Get off my head, can’t you?”

And Bill struggles out, a muddy, trampled wreck, and in an unnecessarily aggressive mood — he being under the evident belief that the whole thing has been done on purpose.

In the morning you are all three speechless, owing to having caught severe colds in the night; you also feel very quarrelsome, and you swear at each other in hoarse whispers during the whole of breakfast time.

Jerome K. Jerome, Three Men in a Boat (to say nothing of the dog), 1889.

December 22, 2014

Repost – Happy Holiday Travels!

H/T to Economicrot. Many many more at the link.

December 12, 2014

Modern parenting: just go right ahead, dear, Mommy’s got your back

Amy Alkon didn’t enjoy her most recent flight … but not because of the TSA goons, scheduling issues, or the ordinary wear and tear of flying. It was an encounter with the most modern, up-to-date parenting style:

I’ll take snakes on a plane. Snakes are quiet.

Last Saturday, I woke up at 4 a.m. to fly to an event across the country. “I’ll sleep on the plane,” I told myself. And no, I wasn’t being naive.

I came prepared: I had my “asshole-canceling headphones” (big Bose over-the-ear “cans”), industrial-grade earplugs to wear underneath, and an iPhone with selections of white noise.

The cute blonde 3-year-old seated in front of me wasn’t a screamer. She was a talker — in a tone and volume appropriate for auditioning for the lead in “Annie.”

I figured she would quiet down after takeoff. She did not. And, sadly, even $300 worth of Bose technology was no match for this kid’s pipes. After about 20 sleep-free, “SUN’LL COME OUT TOMORROW!!” minutes into the flight, I leaned forward and whispered to the child’s mother, “Excuse me, could you please ask your little girl to be a little quieter?”

“No,” the woman said.

No?

No?!

Lucky me, seated behind another proud purveyor of “go-right-ahead!” mommying. And in case you’re wondering, I didn’t ring the call button to “tattle” on her. Those uniformed men and women walking the plane are flight attendants, not nursery school dispute resolution experts. Also, a mother who sees no reason to actually, you know, parent, is unlikely to start because a lady with a pair of wings pinned to her outfit tells her she should.

We experience more and more of this these days — parents who apparently see any correction of their children’s behavior as a form of abuse. We have “parents” like this in my neighborhood. Throughout the day, through closed windows, you can hear this horrible high-pitched screaming. No, nobody’s taken up urban goat slaughter. Those are the impromptu audio stylings of their 3-year-old going underparented.

November 27, 2014

A time-capsule from 1961 – Terminus

Published on 16 Mar 2012

John Schlesinger’s outstanding “fly on the wall” film about a day in the life of Waterloo Station. It was nominated for a BAFTA Film Award for Best Documentary. As well as being a masterpiece of film it has a magnificent soundtrack composed by Ron Grainer (who later composed the Doctor Who theme).

Published Crown copyright material has protection for 50 years from date of publication. Copyright on this film has thus expired.

H/T to Eric Kirkland for the link.

November 23, 2014

QotD: Seasickness

It is a curious fact, but nobody ever is sea-sick — on land. At sea, you come across plenty of people very bad indeed, whole boat-loads of them; but I never met a man yet, on land, who had ever known at all what it was to be sea-sick. Where the thousands upon thousands of bad sailors that swarm in every ship hide themselves when they are on land is a mystery.

If most men were like a fellow I saw on the Yarmouth boat one day, I could account for the seeming enigma easily enough. It was just off Southend Pier, I recollect, and he was leaning out through one of the port-holes in a very dangerous position. I went up to him to try and save him.

“Hi! come further in,” I said, shaking him by the shoulder. “You’ll be overboard.”

“Oh my! I wish I was,” was the only answer I could get; and there I had to leave him.

Three weeks afterwards, I met him in the coffee-room of a Bath hotel, talking about his voyages, and explaining, with enthusiasm, how he loved the sea.

“Good sailor!” he replied in answer to a mild young man’s envious query; “well, I did feel a little queer once, I confess. It was off Cape Horn. The vessel was wrecked the next morning.”

I said:

“Weren’t you a little shaky by Southend Pier one day, and wanted to be thrown overboard?”

“Southend Pier!” he replied, with a puzzled expression.

“Yes; going down to Yarmouth, last Friday three weeks.”

“Oh, ah — yes,” he answered, brightening up; “I remember now. I did have a headache that afternoon. It was the pickles, you know. They were the most disgraceful pickles I ever tasted in a respectable boat. Did you have any?”

For myself, I have discovered an excellent preventive against sea-sickness, in balancing myself. You stand in the centre of the deck, and, as the ship heaves and pitches, you move your body about, so as to keep it always straight. When the front of the ship rises, you lean forward, till the deck almost touches your nose; and when its back end gets up, you lean backwards. This is all very well for an hour or two; but you can’t balance yourself for a week.

Jerome K. Jerome, Three Men in a Boat (to say nothing of the dog), 1889.