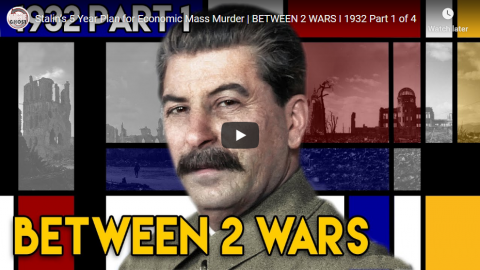

TimeGhost History

Published 1 Apr 2020In 1939, two bitter rivals sign a non-aggression pact. But the treaty is something more than just a simple pledge of neutrality. Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union have also secretly agreed on how they will carve up Eastern Europe between them.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Hosted by: Indy Neidell

Written by: Francis van Berkel

Directed by: Spartacus Olsson and Astrid Deinhard

Executive Producers: Bodo Rittenauer, Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson

Creative Producer: Joram Appel

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: Francis van Berkel

Edited by: Daniel Weiss

Sound design: Marek KamińskiSources:

Bundesarchiv_Bild:

102-14436, 146-1977-159-11, 146-1982-159-22A,

146-1997-060-33A, 183-2006-1010-502, 183-H27337,

183-H28422, 183-R09876, 183-R14433, 183-S52480, RH 2/2292,

Novosti archive, image #409024 / Vladimir GrebnevFrom the Noun Project:

killer with a gun By Arthur Shlain

guns by By Cards Against Humanity,

Shield By Laili Hidayati,Photos from color by klimbim.

Colorizations by:

– Owen Robinson – https://www.instagram.com/owen.colori…

– Dememorabilia – https://www.instagram.com/dememorabilia/Soundtracks from Epidemic Sound:

– “Last Point of Safe Return” – Fabien Tell

– “The Inspector 4” – Johannes Bornlöf

– “Easy Target” – Rannar Sillard

– “Split Decision” – Rannar Sillard

– “Death And Glory 1” – Johannes Bornlöf

– “First Responders” – Skrya

– “Disciples of Sun Tzu” – Christian Andersen

– “Mystery Minutes” – Farrell Wooten

– “Split Decision” – Rannar Sillard

– “Death And Glory 3” – Johannes Bornlöf

– “The Charleston 3” – Håkan ErikssonA TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

From the comments:

TimeGhost History

1 day ago (edited)

If you didn’t think this topic is controversial enough already, we have an even more contentious question for you: Is the Soviet Union basically an Axis Power between 1939 and 1941?Technically the answer is a definite “no” because the USSR will never sign the Tripartite Pact, but it’s still worth thinking about. The USSR and Nazi Germany will cultivate a pretty productive relationship after they sign the Non-Aggression Treaty, not only prompting a joint occupation of Poland but also allowing Hitler to invade Western Europe without having to worry about his eastern borders. So when you look at it like that, the USSR directly supported the Nazi war machine. On the other hand, it is probably a bit of a leap to blame the USSR for Nazi expansionism, and Stalin is forced by circumstances to enter into the Pact. The USSR is not ready to fight a war at this point, and the treaty buys not only time but also space, creating a virtual buffer zone between Germany and the Motherland in the form of Poland. Cynical and calculated, yes, but that’s diplomacy for you. Stalin will obviously offer a very extreme interpretation of this second argument after the war, casting Soviet actions as a necessary defensive measure against the imperialism of the Western Powers and their supposed encouragement of Nazi Germany. Stalinist myth-making aside, the argument that defensive considerations is a significant factor in the Soviets signing of the Pact does have some merit.

This question is more than just an academic exercise. The USSR rightfully gets credit for bearing the brunt of the Nazi onslaught, but would we think differently about it as an Allied power if we also understood as a former Axis power? Let us know what you think below. Stay safe out there.

Cheers, Francis.