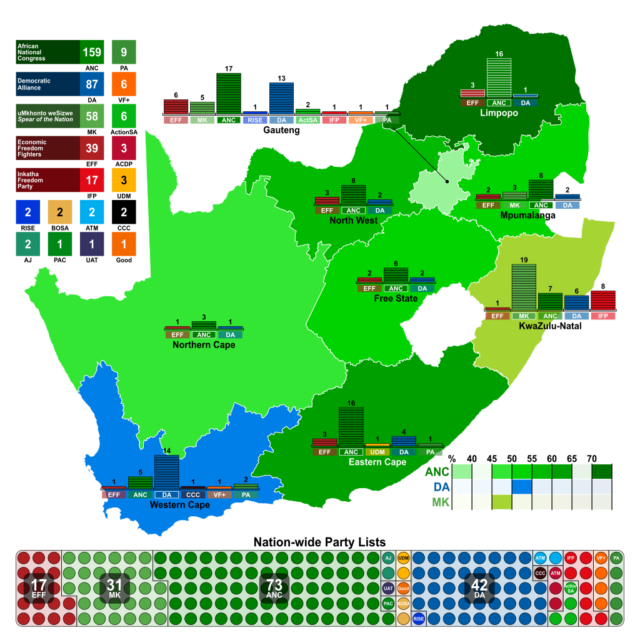

Niccolo Soldo’s weekend roundup includes some quotes from Lawrence Thomas on what he terms a “racketeer party state“, what the “Rainbow Nation” of South Africa has degenerated into since the end of Apartheid:

South Africa is what happens when a country becomes ungovernable. From endemic sexual crime to farm murders, rolling blackouts, and expropriation, the rest is just the details. What has come to be termed “South Africanization” is not the failed development of a Third-World nation such as Afghanistan or Somalia, but the structural de-development of a once fully modern state that had its own nuclear weapons program. President Trump’s support of Afrikaner farmers has brought global attention to the decaying state of the country and is perhaps the most high-level recognition yet that the 1990s “Rainbow Nation” dream is dead. What’s strange about it all is how much of it happened on purpose.

What may be worse is that the very system of law and government itself has become an instrument to be captured and used to further the mass looting of the country. South Africans of all races inherit a Western political culture and economy. The average South African experiences a strong civic identity, highly active political parties, popular national media networks, a market economy, and a parliamentary constitutional order. The last thirty years saw a coalition of political actors, patronage networks, and organized criminal gangs seize control of and use all the infrastructure of modern government for their own ends.

[…]

While songs like “Kill the Boer” at rallies tend to grab headlines, the most consequential development of late is the passing of expropriation without compensation into law by the supposedly moderate President Cyril Ramaphosa. In addition to further eroding property rights, it emboldens a widespread movement that sees land redistribution as the sole resolution to the country’s racial conflict and views the presence of any white population as fundamentally illegitimate. The radicalization of race politics is the means through which political fights are won, since it plays on the country’s major divides and wins over those who feel left out of the spoils.

On the ground, reports tell of ANC officials tacitly allowing invasions of private and public land by squatters. Occupations of this sort have sometimes preceded the farm murders which have gained media attention internationally, and squatters have now begun to invoke the Expropriation Act. Such groups become the shock troops of political pressure: they can harass and pressure the occupants of the lands they occupy, or worse, while becoming a media story about the “landless oppressed” used to justify broader government action. The broad facilitation of ground-level conflict and crime by those with political power is the defining feature of South Africanization.

[…]

In other words, decay is a burden without benefit. There is no “rock bottom”. Business, political organization, social fabric, and all other forms of Western cultural life just face increasing costs. Some are direct, while others are opportunity costs: how much doesn’t happen because almost no one can guarantee electricity? In a relatively developed country, there’s still much more to break down and expropriate.

The combination of social progressivism with an economic model of managed decline has become orthodoxy in many establishment parties across the developed world. South Africa is a study of the political phenomenon in its advanced stage and a demonstration of what is at stake in defeating it in the rest of the Western world. Flip Buys, leader of the Afrikaner trade union Solidariteit, was likely prophetic when he foresaw that South Africa would become home to the “first large grouping of Westerners living in a post-Western country”.

Emphasis from Niccolo’s excerpts.