I have a terrible memory for people’s names (and no, it’s not just early senility … I’ve always had trouble remembering names). For example, I’ve been a member of the same badminton club for nearly 15 years and there are still folks there whose names just don’t register: not just new members, but people I’ve played with or against on dozens of occasions. I know them … I just can’t remember their names in a timely fashion. David Friedman suggests that Google Glass might be the solution I need:

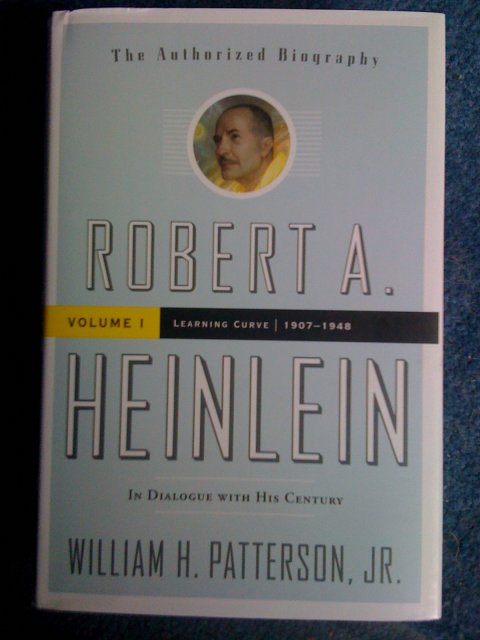

I first encountered the solution to my problem in Double Star, a very good novel by Robert Heinlein. It will be made possible, in a higher tech version, by Google glass. The solution is the Farley File, named after FDR’s campaign manager.

A politician such as Roosevelt meets lots of people over the course of his career. For each of them the meeting is an event to be remembered and retold. It is much less memorable to the politician, who cannot possibly remember the details of ten thousand meetings. He can, however, create the illusion of doing so by maintaining a card file with information on everyone he has ever met: The name of the man’s wife, how many children he has, his dog, the joke he told, all the things the politician would have remembered if the meeting had been equally important to him. It is the job of one of the politician’s assistants to make sure that, any time anyone comes to see him, he gets thirty seconds to look over the card.

My version will use more advanced technology, courtesy of Google glass or one of its future competitors. When I subvocalize the key word “Farley,” the software identifies the person I am looking at, shows me his name (that alone would be worth the price) and, next to it, whatever facts about him I have in my personal database. A second trigger, if invoked, runs a quick search of the web for additional information.

Evernote has an application intended to do some of this (Evernote Hello), but it still requires the immersion-breaking act of accessing your smartphone to look up your contact information. Something similar in a Google Glass or equivalent environment might be the perfect solution.

I finished reading the first volume last night, and I can’t wait for volume two.

I finished reading the first volume last night, and I can’t wait for volume two.