ReasonTV

Published 22 Sep 2022Transit ridership, especially rail, has collapsed post-pandemic, but the Atlanta BeltLine Coalition says now is the time to take federal dollars and build a $2.5 billion streetcar.

Full text and links: https://reason.com/video/2022/09/22/i…

—

Twenty-three years ago, Atlanta-native and architecture and urban planning student Ryan Gravel had an experience that opened his mind to what urban living could be.“My senior year I spent abroad in Paris and lived without a car for a year and traveled by train everywhere,” says Gravel. “And within a month of arriving, I had lost 15 pounds. I was in the best shape of my life because I was walking everywhere, and the role of the physical city was made clear to me in a way it really had never been before.”

For his Georgia Tech master’s thesis, Gravel sketched out a plan to make Atlanta more like Paris. He proposed redeveloping the land along the city’s historic rail lines to create a 22-mile loop called the Atlanta BeltLine. He proposed turning the city’s abandoned industrial areas and single-family home neighborhoods into business districts and walking trails. And he proposed connecting downtown to the rest of the city all with a new train running along the entire Atlanta BeltLine.

“I never imagined we would actually do it,” says Gravel.

But they did — for the most part. Cathy Woolard, who was president of the Atlanta City Council, read Gravel’s thesis and decided to use it as a blueprint to remake much of the city. Today, the Atlanta BeltLine is a walking and biking trail, parts of which are bordered by retail and condos.

But one piece of Gravel’s grand vision didn’t get built: The train.

Today, Gravel runs a co-working and event space along the BeltLine, which also serves as a gathering place for urbanists interested in making Atlanta less dependent on cars. He says that the train line is essential for improving city life.

“In those early days, when we built the movement behind the [BeltLine] project, it was around transit,” says Gravel.

The three COVID relief bills set aside $69 billion in federal funding for local transit agencies to operate and add to their transportation systems, meaning that Atlanta might finally get its train—with many American taxpayers who will never step foot on it picking up much of the tab.

Many American cities have used federal money in the past to build rail transit lines that suffer from dismal ridership, that are expensive to maintain, and that are a major drain on their budgets.

(more…)

September 23, 2022

Is This Atlanta Streetcar “The Worst Transit Project of All Time”?

August 15, 2022

Look at Life – Goodbye, Picadilly (1967)

nostalgoteket

Published 1 Sep 2011U.K. Newsreel. A look at the Piccadilly Circus of the Swinging Sixties! A lot of what is shown here no longer exists as it was soon “modernized” to meet the demands of a changing world. Also a look at underground Piccadilly to see sights that few people have ever seen.

May 12, 2022

Look at Life — Turn of the Wheel (1964)

Classic Vehicle Channel

Published 29 Jan 2021This film, part of the Look At Life series explores the various ways folk put old disused items of transport back into use. Fascinating archive of engines and rolling stock being cut up for scrap and factory footage of the “new” diesel locomotives being assembled. We take a glimpse into the lives of people upcyling railway memorabilia, steam wagons and rollers and there’s great footage of a Wynns Pacific transporting a steam locomotive to a museum.

April 7, 2022

Look at Life – Taxi Taxi – The Knowledge (1960)

March 29, 2022

Abandoned: How The Beeching Report Decimated Britain’s Railways | Timeline

Timeline – World History Documentaries

Published 15 May 2019Travel journalist Simon Calder takes a journey from across the south of England — by bike, rail and car. In this documentary film, Simon explores the legacy of the Beeching railway cuts. He examines the arguments for reopening some of the branch lines axed in the 1960s.

It’s like Netflix for history … Sign up to History Hit, the world’s best history documentary service, at a huge discount using the code ‘

TIMELINE‘ —ᐳ http://bit.ly/3a7ambuYou can find more from us on:

https://www.instagram.com/timelineWH

This channel is part of the History Hit Network. Any queries, please contact owned-enquiries@littledotstudios.com

June 1, 2021

Undoing Dr. Beeching’s cuts

In The Critic, Brice Stratford looks at the British government’s “nationalization if necessary, but not necessarily nationalization” scheme to once again reform Britain’s passenger railway network:

Astonishing scenes this week, whereby the Tory government announces a White Paper to re-nationalise the railways. The union bosses and Guardianistas who have called for such policy for decades immediately decided that actually it’s a terrible idea, or that this doesn’t count as re-nationalising because it’s the Conservatives doing it, or that calling the new entity “Great British Railways” just because it will run Great Britain’s railways is so offensive that the entire project should be called off. It’s all very tribal, and very silly, and very 2021, alas.

Of course, the Department for Transport (DfT) is still afraid of admitting that this is in fact renationalisation, as to do so would be to rile up certain elements of the Right, and to admit what we all know: that their generations-long experiment in railway privatisation has been a failure. Today we have a service which is overpriced, unreliable, and generally an unpleasant and ineffective experience from start to finish.

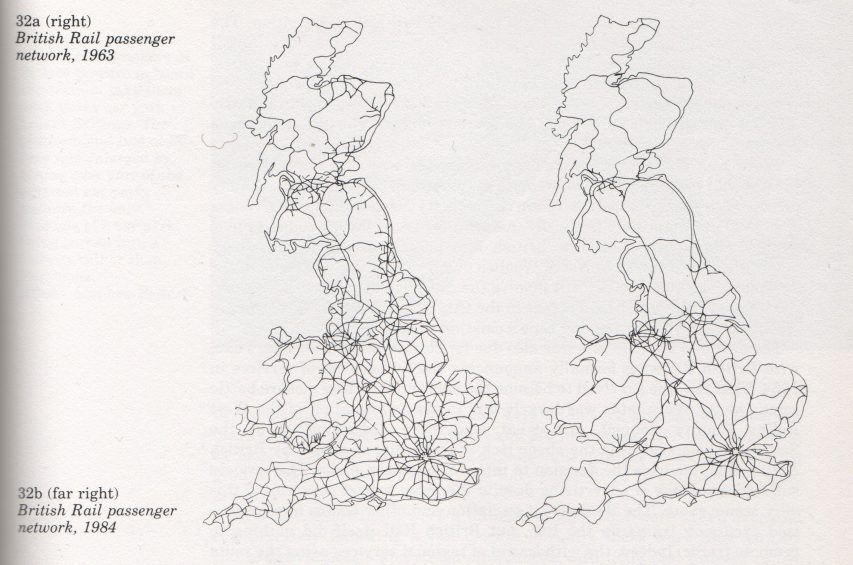

The postwar Labour government included railway nationalization in its many, many reforms to the economic life of Britain and in 1948 the remaining railway systems were unified as British Railways. By the 1960s, the system was losing money at a high rate of speed, so Dr. Beeching was called upon to recommend how to put the railway if not into profit then at least into a much more acceptable rate of loss:

Maps originally from Losing Track by Kerry Hamilton and Stephen Potter (1985), by way of Is Your Journey Really Necessary?, 2012-12-31.

https://isyourjourneyreallynecessary.wordpress.com/2012/12/31/nice-work-if-you-can-get-there/

Click map to enlarge.

The aim of the Beeching cuts, which followed on from a pair of reports written by Dr Richard Beeching in 1963 and 1965 for the British Railway Board (of which he was Chair), was to turn the loss-making British railways network into a profitable enterprise. Prioritising this profitability over all else, he proposed axing about a third of Britain’s then 7000 railway stations, removing passenger service from around 5000 route miles, and cutting 70,000 jobs over three years. The moves were highly controversial, and though they certainly saved money, the social consequences were extensive and the scars remain visible today.

As a consequence of the cuts, Britain became over-reliant on car travel, and over the 1970s and 80s town planners gutted the experientially human-scale city centres in service of this newly favoured road transport. We still very much feel the consequences of the Beeching axe today, whereby a rail journey between neighbouring cities is often only possible by zigzagging up to London and back down again, and public transport between rural communities is limited to one bus service every hour or two in the morning and mid-afternoon, which crawls along at a testudinian pace, further isolating and atrophying the scattered settlements that once were happy, thriving homes.

January 26, 2021

£760m to connect Bicester and Bletchley? That’s … very spendy

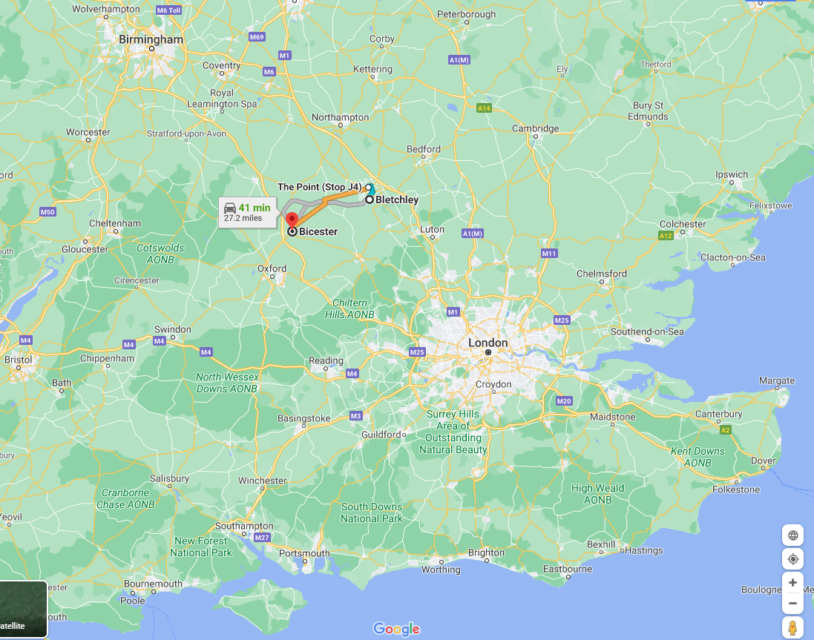

At the Continental Telegraph, Tim Worstall looks at the economic case for building the East-West railway line — in “reverse Beeching” style — to connect Oxford and Cambridge:

The cash from the Department of Transport will be used to lay track along a disused railway line between Bicester and Bletchley, in Buckinghamshire, with services beginning in 2025.

Excuse me? £760m to link Bicester and Bletchley? Other than the fact that that is £50m/mile, which should be the cost of rail lines made from crushed Faberge eggs and unicorn hair, how many people want to travel between Bicester and Bletchley by train? That’s roughly £10K/person in those small towns. OK,that then extends to Oxford, but that allows around 30,000 more people to go by train to Oxford. Which is not a particularly busy commuter metropolis anyway.

The aim is to complete the whole project by the end of the decade, according to the government minister overseeing it.

2 miles per year? Are they going to use canals and horses like Brunel?

[…]

Elsewhere, the new railway will shorten journey times between routes outside of London. Travellers from Oxford for example, will no longer have take a train into the capital and back out again to reach Milton Keynes, but could travel there via Bicester.

Again, what’s the demand for this? How many people want to do this, and would it be cheaper to just hire some chauffeurs to drive each passenger in a Ferrari from Bicester to where they want in Milton Keynes? I doubt it will be any quicker than a car because this only gets you to Bletchley, and then you have to get off a train to get to Milton Keynes, and then get where you want in Milton Keynes.

This used to be an active railway corridor before the Beeching cuts in the 1960s, which slashed a lot of uneconomic branch lines from British Rail’s network. If the land wasn’t sold off, then it’s just a matter of re-laying the track and ensuring that any existing bridges, embankments and drainage culverts are still capable of handling the renewed rail traffic. It seems unlikely that the mere engineering aspects of the project would require several hundred million pounds to complete, so perhaps there are some land issues that need to be re-acquired to allow the railway to become active again.

December 17, 2020

QotD: Light rail systems are almost always an upper middle class boondoggle

What we can see here is exactly what Randall O’Toole of Cato has been saying for years — that light rail projects tend to actually hurt total transit use as they scavenge resources from other modes, like buses. This is because light rail costs so much more to move a passenger, both in terms of capital investment and operating cost, so $X shifted from buses to rail reduces total system capacity and ridership substantially. We have seen this in Phoenix, as light rail costs have forced closing or reduced services in a number of bus routes, with obvious results in the ridership numbers.

[…]

The problem with light rail (and the reason it is popular with government officials) is that it is an upper middle class boondoggle. There can be no higher use of transit than to provide mobility to poorer people who can’t afford reliable automobiles. Buses fulfill this goal better than any mode of transit. They are flexible and can reach into many corners of the city. The problem with buses, from the perspective of government officials, is that upper middle class people don’t like to ride on them. They like trains. So the government builds hugely expensive trains for these influential, wealthier voters. Since the trains are so expensive, the government can only build a few routes, so those routes end up being down upper middle class commuting corridors. As the costs mount for the trains, the bus routes that serve the poor and their dispersed commuting destinations are steadily cut.

Warren Meyer, “Phoenix Light Rail Fail, 2019 Update”, Coyote Blog, 2019-11-13.

November 21, 2020

Schwebebahn: Why Wuppertal’s Trains Are Much Cooler Than Yours

The Tim Traveller

Published 12 Apr 2018Wuppertal has possibly the world’s most badass public transport: a 120-year-old swingin’ suspension railway. But the question is: why? When everyone else was busy building trams and undergrounds, what made Wuppertal say “NOPE”, and build this instead?

***

Tom Scott Video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F4KZL…Kaiserwagen photo:

By Own work – JuergenG, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index…

From the comments:

The Tim Traveller

10 months ago

Hi all – just a quick note on this video: I think a few people are mishearing me at 0:43 where I say this is “the world’s oldest suspension railway… it’s also one of the world’s only suspension railways”. I did not call it “the world’s only suspension railway” — there are others, including one not too far away from here at Düsseldorf Airport, another in Memphis, US, and some more in Japan. TLDR: it’s the oldest one but not the only one. Thank you for your attention

October 8, 2020

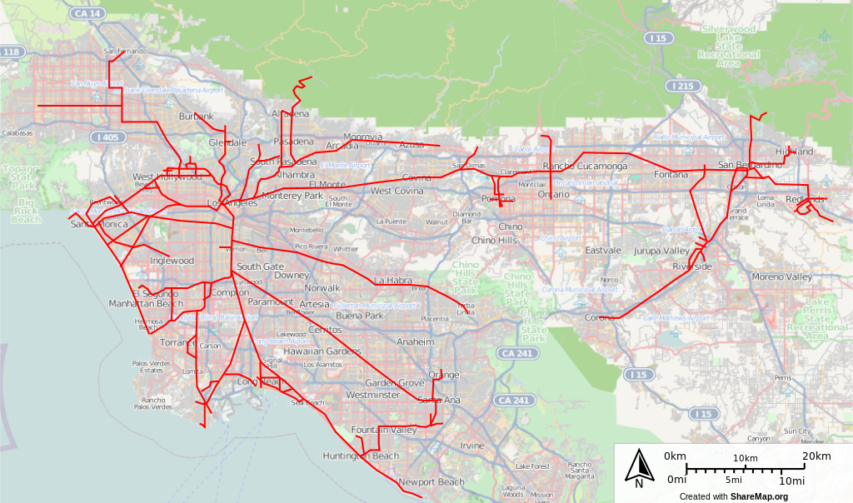

Fallen Flag — The Pacific Electric Railway

This month’s Classic Trains featured fallen flag is southern California’s iconic Pacific Electric Railway Company, whose streetcars, interurbans, and buses served the vast area in and around Los Angeles and San Bernardino from 1901 until the passenger services were sold off in 1953. The electric service was converted to bus and the last electric rail line was discontinued in 1961. At its peak in the 1920s the “Red Cars” service was said to be the largest electric railway system in the entire world.

This month’s Classic Trains featured fallen flag is southern California’s iconic Pacific Electric Railway Company, whose streetcars, interurbans, and buses served the vast area in and around Los Angeles and San Bernardino from 1901 until the passenger services were sold off in 1953. The electric service was converted to bus and the last electric rail line was discontinued in 1961. At its peak in the 1920s the “Red Cars” service was said to be the largest electric railway system in the entire world.

G. Mac Sebree covers the origins of the line in the late nineteenth century:

The story begins in 1895, when a line was completed from Los Angeles to Pasadena; a mere 10 years later, the system was virtually complete. To a great degree, PE was the brainchild of Henry Huntington, nephew of one of the Central Pacific’s “Big Four,” Collis P. Huntington. An active real-estate promoter, Henry needed the Big Red Cars and the transportation they provided to help sell lots and homes in the hinterlands.

His uncle’s Southern Pacific took control of the PE in 1911 in a deal that left the Los Angeles Railway, the narrow-gauge intracity system, in the nephew’s hands. The PE was built to standard gauge, and SP saw a brilliant future in freight for the interurban.

Pacific Electric route map.

Original data from http://sharemap.org/public/Los_Angeles_Pacific_Electric_Railways_(Red_Cars) via Wikimedia Commons.Interurbans were not considered Class I railroads (or any other class — they were not “steam railroads”), but from the very start, PE was big business. The California Railroad Commission said the property was worth $100 million in Depression dollars. Atypically for an interurban, the system served as a gathering network for carload freight shipments from citrus groves, manufacturing plants, oil refineries, warehouses, and the harbor at San Pedro. The three line-haul railroads serving southern California — Santa Fe, Union Pacific, and especially SP — depended on the Pacific Electric to some degree.

Yet in its heyday, PE carried huge numbers of passengers. As late as 1953, 50 percent of its revenue came from riders — but absolutely none of its profit. An all-time list shows that PE operated 143 distinct passenger routes. Despite the so-called “Great Merger of 1911,” in which local and interurban services were supposedly separated, the heaviest PE passenger lines largely served the L.A. urban area. An example was the street-running L.A.–Hollywood–Beverly Hills line, in which two-car trains rumbled down Hollywood Boulevard at 10-minute intervals.

At one time or another, PE single-truck Birney cars plied local lines in Pasadena, Long Beach, Santa Monica, Redlands, Santa Ana, and San Pedro, although the 1920s were not far along before management sought to sell off or abandon these albatrosses.

After World War 2, the writing was on the wall for the Red Cars, as urban expansion and greatly increased car ownership cut at the economic basis for rail passenger service in southern California, especially as the new freeways were built.

After the war, though, things went downhill rapidly. As soon as buses were available, Pacific Electric began wholesale rail passenger-service abandonments. The new freeways were regarded as the rapid transit of the future. PE President Oscar Smith saw one possibility for saving rail service — if the state would pay. Just before the war, a short section of freeway between Hollywood and the San Fernando Valley had been built, with the PE tracks relocated to the center of the new highway.

Why not replicate this all over the basin? The PE would cooperate, but public officials turned a deaf ear, and that was that. Freight service, meanwhile, prospered, but by the mid-1950s, PE began replacing its electric locomotives and box motors with diesels (a few steam locomotives also had been used during the war). Over the years, PE rostered about 100 electric locomotives and at least 75 box motors — big business, indeed.

In 1953, PE sold its passenger service (four rail lines out of the 6th and Main station, two out of Subway Terminal, and many bus lines) to Metropolitan Coach Lines. The Metropolitan Transit Authority, first formed in 1951, bought MCL on March 3, 1958, and the end for electric passenger service came in 1961. SP continued the freight work with diesels, and merged PE away on August 13, 1965. Today under the Union Pacific shield, a good bit of the old PE freight lines remain in service, unique survivors, busier than ever.

September 22, 2020

QotD: City dwellers and the state

If one wants to understand why city dwellers have a peculiarly statist politics, spend time in a big city subway system. For the people in the city, government services are essential for living. They depend on the subway, the trash collection and the police department. The city depends upon this organic relationship between the state and the citizens. That does not exist in the suburbs or the country. There’s a comfort that comes from the daily interaction with the state. Anyone who questions that relationship is suspect.

The Z Man, “Never Newark Nights”, The Z Blog, 2018-06-06.

August 19, 2020

He calls it “unintended consequences”. I disagree … these consequences are very much intended

Brad Polumbo is being far too generous to Californian politicians by saying the impending collapse of the state’s entire gig economy was not the intended result of passing “worker protection” laws that penalized success:

UBER 4U by afagen is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

This Friday, Uber and Lyft are set to entirely shut down ride-sharing operations in California. The businesses’ exit from the Golden State will leave hundreds of thousands of drivers unemployed and millions of Californians chasing an expensive cab. Sadly, this was preventable.

Here’s how we got to this point.

In September of 2019, the California state legislature passed AB 5, a now-infamous bill harshly restricting independent contracting and freelancing across many industries. By requiring ride-sharing apps such as Uber and Lyft to reclassify their drivers as full employees, the law mandated that the companies provide healthcare and benefits to all the drivers in their system and pay additional taxes.

Legislators didn’t realize the drastic implications their legislation would have; they were simply hoping to improve working conditions in the gig economy. The unintended consequences may end up destroying it instead.

Here’s why.

AB 5 went into effect in January, and now, a judge has ordered Uber and Lyft to comply with the regulation and make the drastic transformation by August 20. Since compliance is simply unaffordable, the companies are going to have to shut down operations in California.

Their entire business model was based upon independent contracting, so providing full employee benefits is prohibitively expensive. Neither Uber nor Lyft actually make a profit, and converting their workforce to full-time employees would cost approximately $3,625 per driver in California. As reported by Quartz, “that’s enough to boost Uber’s annual operating loss by more than $500 million and Lyft’s by $290 million.”

Essentially, California legislators put these companies in an impossible position. It makes perfect sense that they’d leave the state in response. It’s clear that despite the good intentions behind the ride-sharing regulation, this outcome will leave all Californians worse off.

June 14, 2020

June 3, 2020

Fanatics gonna fanatic … they can’t help it

It’s funny that no matter what the claimed crisis, the answers always go in the same direction, as Kristian Niemietz points out with the demands to turn our still unending lockdown toward “protecting the environment”:

The change, superficially, is to encourage “a safe return to work” allowing more social distancing between pedestrians, but more substantially in order to preserve the cleaner air that has resulted from the lockdown.

The health and safety excuse for the policy change can be largely dismissed. The simple truth of the pandemic and national policy is that if social distancing matters, the centre of London is not safe to return to work. It is too densely populated and almost entirely reliant on mass transit which cannot operate above 10-15% capacity with 2m exclusion rules. With average commutes over 9 miles each way, substitution effects to walking and cycling will be extremely limited and temporary.

It is then hard to see then how the policy’s architects imagine the streets will fill up to the extent urgent measures are needed. Conversely, if social distancing does not matter (and it will cease to matter eventually), then a policy to enable more social distancing outside by widening the pedestrian streetscape is redundant. If it is safe to sit on a crowded train, it is safe to walk on a crowded pavement. It is not hard then to cut through the pandemic packaging to note that the motive for this policy is opportunistic, to accelerate a pedestrianisation plan that is the dream of many an urban planner.

Many will see this as self-evidently a good thing. Removing vehicle traffic from densely populated narrow streets will reduce air pollution, congestion and road traffic accidents. As a policy it will have more supporters than opponents; very few people drive into the centre of London to commute and there is very little capacity for parking. London’s leaders are not wrong to think that this is the future, the question is really one of timing and how they go about it, which is far more difficult and does not have anything to do with managing a coronavirus.

What the pandemic allows is the ability to use emergency powers for something that is not an emergency. This matters, in normal times it took several years to close one dangerous junction at Bank to most traffic, and this under a hail of protests from local businesses and taxi drivers. The same result can now be achieved in a few weeks across many streets. The democratic checks and balances that differentiate the UK from authoritarian states can be ditched and London officialdom granted extraordinary powers to do as they please. If the protestors don’t like it this time, they should note the right to protest has also been suspended, at least for now.

April 20, 2020

“New York City subways were ‘a major disseminator — if not the principal transmission vehicle — of coronavirus infection'”

Randal O’Toole wonders why the lone sacred cow of mass transit is still running, despite its potential role in spreading disease:

Sit‐down restaurants and bars have been shut down. Public officials are discouraging or even forbidding people from doing “unnecessary travel,” even if it is to visit a second home where they might be able to socially distance themselves better than in their first, more urban home. All sorts of other rules are being passed, all supposedly for our own good.

So why are urban transit systems still running? A 2018 study found that “mass transportation systems offer an effective way of accelerating the spread of infectious diseases.” A 2011 study found that people who use mass transit were nearly six times more likely to have acute respiratory infections than those who don’t. Not surprisingly, a study published a few days ago found that New York City subways were “a major disseminator — if not the principal transmission vehicle — of coronavirus infection.”

Transit agencies say they are helping “essential workers” go about their business. But if they are so essential, isn’t it important to find them a safe way of getting to work? If we truly cared about people’s safety, then transit services should have shut down at the same time we closed other non‐essential businesses and asked people to stay at home.

[…]

Unfortunately, the transit lobby has successfully turned government‐subsidized transit into a sacred cow. Transit is supposedly greener than driving when in fact it’s an energy hog. Transit is supposedly needed to help poor people get to work when in fact the people most likely to commute by transit are those earning more than $75,000 a year.

When the pandemic took away most of transit’s customers, instead of shutting down, which would have been the responsible thing to do, transit agencies demanded that Congress give them $25 billion, tripling federal support to transit this year. Thanks to transit’s sacred cow status, Congress agreed without any serious debate.

Effectively, Congress rewarded the agencies for spreading disease. It would have been better to use that money to help transit‐dependent essential workers buy a car so they could have a safe way of getting to work.