The latest book review from the Psmiths is Bernard Yack’s The Longing for Total Revolution: Philosophic Sources of Social Discontent from Rousseau to Marx and Nietzsche, by John Psmith:

This is a book by Bernard Yack. Who is Bernard Yack? Yack is fun, because for a mild-mannered liberal Canadian political theorist he’s dropped some dank truth-bombs over the years. For example, check out his short and punchy 2001 journal article “Popular Sovereignty and Nationalism” if you need a passive-aggressive gift for the democratic peace theorist in your life.1 The subject of that essay is unrelated to the subject of the book I’m reviewing, but the approach, the method, and the vibe are similar. The general Yack formula is to take some big trendy topic (like “nationalism”) and examine its deep philosophical and intellectual substructure while totally refusing to consider material conditions. He’s kind of like the anti-Marx — in Yack’s world not only do ideas have consequences, they’re about the only things that do. Even when this is unconvincing, it’s usually very interesting.

The topic of this book is radicalism in the ur-sense of “a desire to get to the root”. What Yack finds interesting about radicalism is that it’s so new. It’s a surprising fact that the entire idea of having a revolution, of burning down society and starting again with radically different institutions, was seemingly unthinkable until a certain point in history. It’s like nobody on planet Earth had the idea, and then suddenly sometime in the 17th or 18th century a switch flips and it’s all anybody is talking about. We’re used to that sort of pattern for scientific discoveries, or for very original ways of thinking about the universe, but “let’s destroy all of this and try again” isn’t an incredibly complex or sophisticated thought, so why did it take so many millennia for somebody to have it?

Well, first of all, is this claim even true? One thing you do see a lot of in premodern history is peasant rebellions, but dig a little deeper into any of them and the first thing you notice is that (sorry vulgar Marxists)2 there’s nothing especially “revolutionary” in any of these conflagrations. The most common cause of rebellion is some particular outrage, and the goal of the rebellion is generally the amelioration of that outrage, not the wholesale reordering of society as such. The next most common cause of rebellions is a bandit leader who is some variety of total psycho and gets really out of control. But again, prior to the dawn of the modern era, these psychos led movements that were remarkably undertheorized. The goal was sometimes for the psycho to become the new king, sometimes the extinguishment of all life on earth, but you hardly ever saw a manifesto demanding the end of kings as such. Again, this is weird, right? Is it really such a difficult conceptual leap to make?

Peasant rebellions are demotic movements, but modern revolutions are usually led by frustrated intellectuals and other surplus elites. When elites did get involved in pre-modern rebellions, their goals were still fairly narrow, like those of the peasants — sometimes they wanted to slightly weaken the power of the king, other times they wanted to replace the king with his cousin. But again this is just totally different in kind from the 18th century onwards, when intellectuals and nobles are spending practically all of their time sitting around in salons and cafés, debating whose plan for the total overhaul of society, morality, and economic relations is best.

The closest you get to this sort of thing is the tradition of Utopian literature, from Plato’s Republic to Thomas More, but what’s striking about this stuff is how much ironic distance it carried — nobody ever plotted terrorism to put Plato’s or More’s theories into practice. Nobody ever got really angry or excited about it. But skip forward to the radical theorizing of a Rousseau or a Marx or a Bakunin, and suddenly people are making plans to bomb schools because it might bring the Revolution five minutes closer. So what changed?

Well this is a Bernard Yack book, so the answer definitely isn’t the printing press. It also isn’t secularization, the Black Death, urbanization, the Reformation, the rise of industrial capitalism, the demographic transition, or any of the dozens of other massive material changes that various people have conjectured as the cause of radical political ferment. Instead Yack points to two abstract philosophical premises: the first is a belief in the possibility of “dehumanization”, the idea that one can be a human being and yet be living a less than human life. The second is “historicism” in the sense of a belief that different historical eras have fundamentally different modes of social interaction.

Both views had some historical precedent (for instance historicism is clearly evident in the writings of Machiavelli and Montesquieu), but it’s their combination that’s particularly explosive, and Rousseau is the first person to place the two elements together and thereby assemble a bomb. Because for Rousseau, unlike for any of the ancient or medieval philosophers, merely to be a member of the human species does not automatically mean you’re living a fully-human life. But if humanity is something you can grow into, then it’s also something that you can be prevented from growing into. Thus: “that I am not a better person becomes for Rousseau a grievance against the political order. Modern institutions have deformed me. They have made me the weak and miserable creature that I am.”

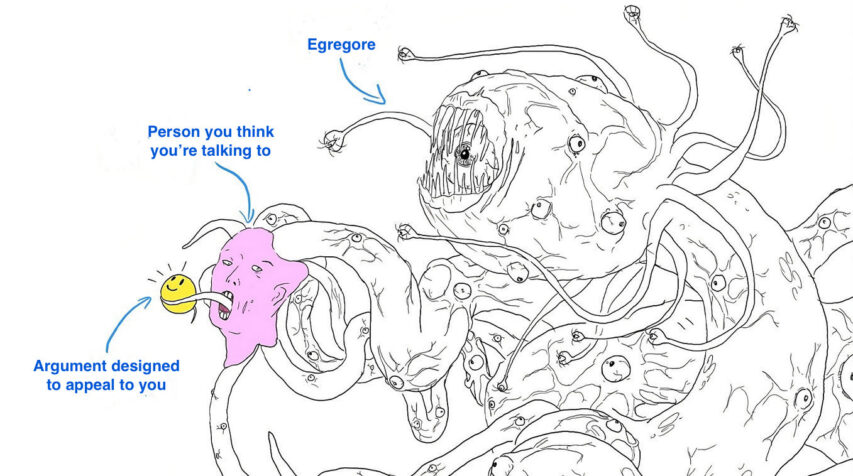

But what if the qualities of social interaction which have this dehumanizing effect are inextricably bound up with the dominant spirit of the age? In that case, it might be impossible to really live, impossible to produce happy and well-adjusted human beings, without a total overhaul of society and all of its institutions. This also clarifies how the longing for total revolution is distinct from utopianism — utopian literature is motivated by a vision of a better or more just order. Revolutionary longing springs from a hatred of existing institutions and what they’ve done to us. This is an important difference, because hate is a much more powerful motivator than hope. In fact Yack goes so far as to say (in a wonderfully dark passage) that the key action of philosophers and intellectuals upon history is the invention of new things to hate. Can you believe this guy is Canadian?

1. Of course, if my reading of MITI and the Japanese Miracle is correct, popular sovereignty may not be around for that much longer.

2. I say “vulgar” Marxists, because for the sophisticated Marxists (including Marx himself) it’s already pretty much dogma that premodern rebellions by immiserated peasants aren’t “revolutionary” in the way they care about.