History Matters

Published 25 Aug 2019Twitter: https://twitter.com/Tenminhistory

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/user?u=4973164

Merch: teespring.com/stores/history-matters-…Special Thanks to the following Patrons for their support on Patreon:

Kevin Sanders

Chris Fatta

Daniel Lambert

Richard Wolfe

Joshua

Tom Loghrin

Warren Rudkin

Andrew Niedbala

Mitchell Wildoer

Blaine Tillack

Bernardo Santos

Matthew

John Garcia

Richard Hartzell

Will Davis-Coleman

Danny Anstess

Henry Rabung

August Block

Perry Gagne

Shaun Pullin

Joooooshhhhh

Vesko Dinev

PaulToon

Kelly Moneymaker

FuzzytheFair

Armani_Banani

Jeffrey Schneider

Byzans_Scotorius

Seth Reeves

Haydn Noble

Josh Cornelius

Gideon Rashkes

Spencer Smith

Cornel Borină

Roberto

Andrew Keeling

Richard Manklow

Chance Cansler

João Santos

Gabriel Lunde

Pierre Le Mouel

anonHow did the Holy Roman Empire work? It was an antiquated mess but it did have a system of government that did work. Sort of. If everyone felt like it.

Sources:

Prussia’s Relations with the Holy Roman Empire, 1740-1786 by Peter H. Wilson.

Benjamin Franklin, Student of the Holy Roman Empire: His Summer Journey to Germany in 1766 and His Interest in the Empire’s Federal Constitution by Jürgen Overhoff.

The Constitution of the Holy Roman Empire after 1648: Samuel Pufendorf’s Assessment in His Monzambano by Peter Schröder.

Bolstering the Prestige of the Habsburgs: The End of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806 by Peter H. Wilson.

February 8, 2021

How did the Holy Roman Empire Work?

October 7, 2020

Ten Minute History – The French Revolution and Napoleon

History Matters

Published 12 Sep 2016Twitter: https://twitter.com/Tenminhistory

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/user?u=4973164This episode of Ten Minute History (like a documentary, only shorter) covers the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars from the beginning of King Louis XVI’s reign all the way to the death of Napoleon Bonaparte in 1821. The first half covers the life and death of Louis XVI during the events of the revolution, including the rise and fall of Robespierre and the Reign of Terror. The second half covers the rise of Napoleon, the Napoleonic Wars and the eventual allied victory over France.

Ten Minute History is a series of short, ten minute animated narrative documentaries that are designed as revision refreshers or simple introductions to a topic. Please note that these are not meant to be comprehensive and there’s a lot of stuff I couldn’t fit into the episodes that I would have liked to. Thank you for watching, though, it’s always appreciated.

October 5, 2020

Napoleonic Wars: Battle of Marengo, 1800

Kings and Generals

Published 1 Oct 2017Napoleon Bonaparte is one of the most talented military leaders in the history, so every battle he fought is fascinating, as well as his complete knowledge of tactical and strategic aspects of the war. He was part of the French Revolution and ended it, he was the biggest conqueror of Europe, but also brought its unity closer. The battle of Marengo of 1800, which took place during the War of the Second Coalition between Napoleon and Austrian troops under Baron Michael von Melas is interesting, as French leader committed a big mistake, but was able to score a big victory through sheer will and tactical acumen.

Support us on Patreon: http://www.patreon.com/KingsandGenerals or Paypal: http://paypal.me/kingsandgenerals

We are thankful to our patreons, who made this video possible: Koopinator, Ibrahim Rahman, Daisho, Łukasz Maliszewski, Nicolas Quinones, William Fluit and Juan Camilo Rodriguez

This video was narrated by good friend Officially Devin. Check out his channel for some kick-ass Let’s Plays. https://www.youtube.com/user/Official…

✔ Twitch ► https://www.twitch.tv/nurrrik_phoenix

✔ Twitter ► https://twitter.com/KingsGenerals

✔ Instagram ► https://www.instagram.com/nurrrrrik

✔ Steam ► http://steamcommunity.com/id/nurrrikPrimary sources used:

Chandler, David (1966). Campaigns of Napoleon. Scribner.

Hollins, David (2000). The Battle of Marengo 1800. Osprey Publishing

Тарле Е. В. Наполеон // Собрание сочинений: в 12 томах. — М.: Издательство АН СССР, 1959.Inspired by: BazBattles, Invicta (THFE), Epic History TV and Historia Civilis, Time Commanders

Machinimas made on Napoleon: Total War

Production Music courtesy of Epidemic Sound: http://www.epidemicsound.com, Napoleon: Total War

Songs used:

Richard Beddow – “Napoleon Bonaparte” – Total War Napoleon Soundtrack

Peter Sandberg – “Subtle Substitutes 3”

Johannes Bornlof – “Solemn”

Magnus Ringblom – “Marching In”

Johannes Bornlof – “Exile Before Dishonor”

Rannar Sillard – “Emperors of Tomorrow 13”

Rannard Sillard – “Deathmatch 3”

Johannes Bornlof – “Barbarians”

September 29, 2020

Frederick the Great – A First Glance

Military History not Visualized

Published 22 May 2018» patreon – https://www.patreon.com/mhv

Frederick the Great – Friedrich der Große – is a very controversial figure. Regarded by many as one of the great field commanders of his time, enlightened, strict, aggressive and militaristic. For a long time he was the example and icon of the Prussian general staff. What were his characteristics, traits, his background and his views on various military issues? After all, he wrote about the principles of war and other aspects.

»» SUPPORT MHV ««

» patreon – https://www.patreon.com/mhv

» paypal donation – https://www.paypal.com/cgi-bin/webscr…

» Book Wishlist https://www.amazon.de/gp/registry/wis…»» MERCHANDISE – SPOILS OF WAR ««

» shop – https://www.redbubble.com/people/mhvi…»» SOCIAL MEDIA ««

» minds.com – https://www.minds.com/militaryhistory…

» twitter – https://twitter.com/MilHiVisualized

» twitch – https://www.twitch.tv/militaryhistory…

» RallyPoint – https://www.rallypoint.com/organizati…Military History for Adults is a support channel to Military History Visualized with a focus personal accounts, answering questions that arose on the main channel and showcasing events like visiting museums, using equipment or military hardware.

» SOURCES «

Showalter, Dennis: Frederick the Great. A Military History. Frontline Books: London, 2016.

Militärgeschichtliches Forschungsamt (Hrsg.): Friedrich der Große und das Militärwesen seiner Zeit. Vorträge zur Militärgeschichte – Band 8. E. S. Mittler & Sohn: Herford – Bonn, 1987.

Clark, Christopher: The Iron Kingdom. The Rise and Downfall of Prussia 1600-1947. Penguin Books: London, 2007.

Citino, Robert M.: The German Way of War. From the Thirty Years’ War to the Third Reich. University Press of Kansas: USA, 2005.

Militärgeschichtliches Forschungsamt (Hrsg.): Deutsche Militärgeschichte 1648-1939 in sechs Bänden – Band 6. Bernard & Graefe Verlag; München, 1983.

Browing, Peter: The Changing Nature of Warfare. The Development of Land Warfare from 1792 to 1945. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002.

Margiotta, Franklin D.: (Executive Editor): Brassey’s Encyclopedia of Military History and Biography. Brassey’s, Inc.: USA, 1994.

» CREDITS & SPECIAL THX «

Song: Ethan Meixsell – “Demilitarized Zone”

June 13, 2020

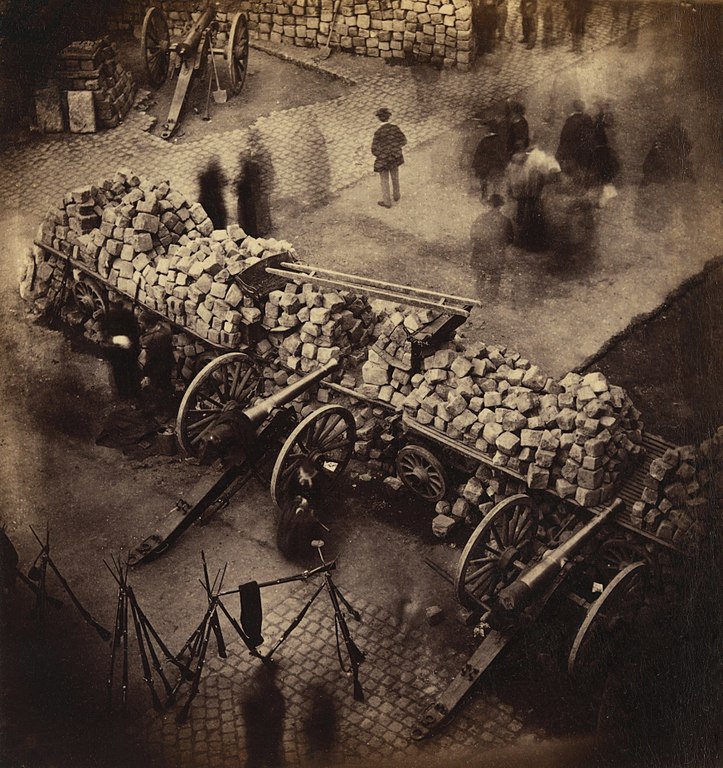

The CHAZ is a little bit 1968, a little bit 1789, but perhaps more 1871

Lawrence W. Reed finds the developments in the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone of Seattle remind him of the Paris Commune:

“‘Autonomous zone’ has armed guards, local businesses being threatened with extortion.”

That was quite a striking headline to behold. My immediate reaction was, “Oh my gosh, the Paris Commune is back!”

Except that it wasn’t Paris, and it wasn’t 1871. It was Seattle, Washington, USA — today. According to multiple reports, radical protesters seized a six-block area of the city. They declared it a police-free fiefdom, posted armed guards at its perimeter, began extorting money from local businesses (normally called “taxation”) and were even requiring residents to provide ID to enter their own homes.

The Paris Commune that lasted just 70 days in the spring of 1871 was born amid the ruins of France’s wartime loss at the hands of Prussia in the fall of the previous year. When the Prussians captured France’s Emperor Napoleon III, the monarchy collapsed, and the French Third Republic was born. In Versailles, just a few miles from Paris, its leaders sat on their hands as Parisians stewed in the toxic juices of defeat, resentment, and a rising tide of Marxist-inspired class warfare. The voices of the big mouths increasingly drowned out those of the more moderate citizens who preferred to get the city back to normal and work for a living.

On March 18, 1871, the socialist radicals seized the upper hand in the City of Lights. They occupied government buildings and ousted or jailed their opposition. It was a “People’s Revolution” (unless you were one of the people who didn’t support it). Karl Marx’s communist scribblings provided the radicals — called “Communards” — with their primary inspiration, but Marx himself later criticized their failure to immediately seize the Bank of France and march on the government in Versailles. In the early days of the Paris Commune, however, he hoped he was witnessing a fulfillment of his own delusions:

The struggle of the working class against the capitalist class and its state has entered upon a new phase with the struggle in Paris. Whatever the immediate results may be, a new point of departure of world-historic importance has been gained.

June 12, 2020

History of Prussia | Animated History

The Armchair Historian

Published 14 Sep 2018Sign up for The Armchair Historian website today:

https://www.thearmchairhistorian.com/Our Twitter: https://twitter.com/ArmchairHist

Sources:

The Rise and Fall of Prussia, Sebastian Haffner

Germans and Slavs, Arno Lubos

Frederick the Great, Tim BlanningMusic:

“Hungarian Rhapsody” by Franz Liszt“Twenty six variations on La Folia de Spagna”, London Mozart Players

Matthias Bamert, conductor*Correction 1: In 1648, Brandenburg-Prussia also acquired parts of Pomerania, which isn’t shown in the video. Pomerania is a state directly above Brandenburg.

December 11, 2019

Franco-Prussian War | Animated History

The Armchair Historian

Published 4 Feb 2018What was the Franco Prussian War?

Our Website: https://www.thearmchairhistorian.com/

Our Twitter:

@ArmchairHistOur Discord:

https://discord.gg/Ppb2cUdSources:

https://www.britannica.com/event/Fran…

http://francoprussianwar.com/

http://history-world.org/franco_pruss…

http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/e…

https://www.warhistoryonline.com/hist…

http://geacron.com/home-en/?v=m&lang=…Music: Music: Antonio Salieri: “Twenty six variations on La Folia de Spagna“

November 21, 2019

Battle of Sedan: How did Prussia Win The Franco-Prussian War? | Animated History

The Armchair Historian

Published 16 Feb 2018The Battle of Sedan. How did Prussia Win the Franco-Prussian War?

Our Website: https://www.thearmchairhistorian.com/

Our Twitter:

@ArmchairHistOur Discord:

https://discord.gg/Ppb2cUdSources:

http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-Q9vpKOSgFHs…

https://www.britannica.com/event/Batt…

https://www.thoughtco.com/franco-prus…

https://www.warhistoryonline.com/hist…

https://www.military-history.us/2011/…100 Decisive Battles by: Paul K. Davis

50 Battles That Changed the World by: William WeirMusic: “Danse Macabre” by Kevin MacLeod is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/…)

Source: http://incompetech.com/music/royalty-…

Artist: http://incompetech.com/

September 8, 2019

How Did War Become a Game?

Invicta

Published on 28 Jun 2019Get your first audiobook and two Audible originals when you try Audible for 30 days. Visit https://www.audible.com/Invicta or text “Invicta” to 500 500!

In this video we continue to take a look at the history of Kriegsspiel and explore the early days of wargaming that eventually gave rise to modern table top games such as Warhammer and Dungeons & Dragons.

Research: Jon Peterson

Script: Invicta

Narration: Invicta

Artwork: Gabriel Cassata

Editing: InvictaBibliography

Playing at the World by Jon Peterson

Debugging Game History: A Critical Lexicon by Henry Lowood

War Games: A History of War on Paper by Philipp von Hilgers

Pluie de Balles – Complex Wargames In the Classroom by Jorit Wintjes and, Steffen Pielstrom

August 8, 2019

QotD: Austrians – strudel-eating surrender monkeys

Oh yes, did I mention the Austrians? A grand military tradition. The Radetzky march, all that stuff. Let’s look at their record more closely, shall we?

The Austrians (or rather the Habsburgs) built up a moderately large empire by persuading the Magyars that they could be sort of equal partners in the empire in an unequal sort of way, expert politicking and setting one lot of Slavs against another in the Balkans and central Europe, and marrying into the right ducal families in bits of what was later to become Italy. They never quite managed to sort out the Serbs, however, who felt that fighting nobly against the Turks was their speciality, and they were forced out of Switzerland early on by a small boy with an apple on his head.

The year 1683 may reasonably be considered a turning point for Western Christendom. Over the preceding century or so the Turkish Ottoman Empire had steadily advanced up the Balkan peninsula and after being balked, as it were, for many years by Macedonians, Bulgars, Albanians, Serbs, Bosnians, Croats, Slovenians, Slavonians and some I’ve probably forgotten, finally got as far as the Habsburg capital, Vienna, to which they laid siege. The siege failed, and the Turks were repelled, never again to return. Why? Because Austria was rescued by the Poles under Jan III Sobieski.

Under the noted and renowned Empress Maria Theresa, a War of the Austrian Succession was held. In keeping with tradition, it was mainly fought between the French and the English in Belgium (the French, opposed to Austria, won), except for an unimportant sideshow which appears to have been between the French and the Indians in Saratoga. The upshot was naturally that the Austrians let the Prussians have Silesia. Twice, to be on the safe side. A few years later the Seven Years War, largely fought between the English and the French in Belgium (the English, opposed to the Austrians, won) confirmed the result.

When it came to the French revolutionary and the Napoleonic wars, the Habsburgs were naturally on the side of the divine right of kings (well, Marie-Antoinette was a Habsburg herself) and against mob rule, liberty, fraternity, and most certainly equality. In furtherance of this cause, the Austrians fought the French at such places as Marengo, Austerlitz, and Wagram – among other names listed on the Arc de Triomphe in Paris. By 1812 the Austrians decided to try being on the same side as Napoleon for a change. Napoleon promptly invaded Russia, with predictable results. Following Napoleon’s final defeat at a battle in Belgium which the Austrians fortunately weren’t in time to get to, they regained most of their possessions in Italy at the peace talks due to diplomatic manoeuvrings by the master of the art, Metternich, but lost influence in Germany.

In the 1850s Austria failed to back her treaty partner Russia when the latter was invaded by the Turks, French and English in the Crimean war. Sardinia/Savoy/Piedmont, the leading state in the Italian peninsula, fought with the Allies, gaining international favour when it came to removing the Austrian influence during the subsequent wars of the Italian unification. Austria lost battles at places like Magenta and Solferino, and with them most of its Italian possessions except Venice.

In 1864 the Austrians did actually win a battle, a small naval engagement near Heligoland in the North Sea, against the Danes, against whom they were fighting in support of the Prussians over the Schleswig-Holstein question, of course. Emboldened by this masterstroke, they promptly came to blows with their erstwhile allies and were soundly whipped at the battle of Sadowa-Königgratz. The Italians got most of the rest of their country back in the resulting confusion.

The Austrians managed to stay out of trouble for another few decades after that, building up a national economy based on cheap dance music and diplomatic manoeuvrings in the Balkans. Unfortunately they got out of their depth in this respect; in 1914 the foreign minister [actually Chief of the General Staff] Conrad von Hötzendorff, believing himself to be the reincarnation of Metternich, decided to start the First World War to impress a woman he fancied. It could reasonably be argued that all the countries involved lost the First World War, even the winners, but Austria, after some Pyrrhic successes against the Serbs, a certain amount of back-and-forth against the Russians in Galicia and a cheap and ultimately futile win at Caporetto after the Russians had pulled out and the Germans had sent rather a lot of extra troops, ended up losing its entire empire, its monarchy, access to the sea and any self-respect whatsoever. It also managed to export Adolf Hitler to Germany during this period, which was singularly unfortunate; he absorbed Austria into a Greater Germany and then lost a rather big war in the most spectacular of fashions, as you are probably aware. This ended the military involvement of Austria in world affairs, at least for the moment.

I rest my case.

Albert Herring, “Why neither the French nor the Italians are the worst military nation”, Everything2, 2002-01-07.

April 14, 2019

British diplomatic blunders in history – German unification

An interesting article in Vox, suggesting that the gradual unification of all the German principalities, electorates, duchies, counties, bishoprics, free cities, and miscellaneous other semi-independent bits and bobs of the Holy Roman Empire was not inevitable and that — absent British blundering after the Napoleonic wars — it would have produced a very different 20th century:

The Holy Roman Empire in 1789, before Napoleon “rationalized” hundreds of smaller entities into the Confederation of the Rhine.

Image from Wikimedia Commons.

The boundaries of states are the heart of many recent debates, be it the European refugee crisis, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), or Brexit (Snower and Langhammer 2019). After decades of stability, today we are again seeing heated discussions about the shape and extent of political borders. Clearly, borders are neither naturally given nor random. In Europe and elsewhere, the current state borders have been formed and changed over centuries, sometimes peacefully, often in bloody wars. In Huning and Wolf (2019), we look at the formation of the German nation state led by Prussia and trace it back to a change in borders decided at the Congress of Vienna in 1814/15.

In a nutshell, we have two findings:

- First, the geographic position of a state can be a crucial factor for institutional change and development.

- Second, the formation of the German Zollverein in 1834 under Prussian leadership was a truly European story, involving Britain, the Russian Empire, and the Belgian revolution of 1830/31. We show in particular that the Zollverein formed as an unintended consequence of Britain’s intervention in 1814/15 to push back Russian influence over Europe.

In theory, why would the geographic position of a state relative to that of other states matter? Intuitively, it should matter as long as the costs of trade and factor flows depend on their routes. If a large share of my trade has to pass the territory of one or several neighbours, my trade and trade policy will depend on the trade policy of my neighbours. Moreover, if tariffs are levied not only on imports but also on transit trade, as was general practice until the Barcelona Statute of 1921 (Uprety 2006), policymakers face the problem of multiple marginalisation, which is well known from the literature on supply chains. In our work, we provide a simple theoretical framework (in partial equilibrium) to show how the location of a revenue maximising state planner will affect its ability to set tariffs. Some states can increase their tariff revenue at the expense of their hinterland. Next, we show that a customs union can be beneficial for a group of states exactly because it solves the problem of multiple marginalisation.

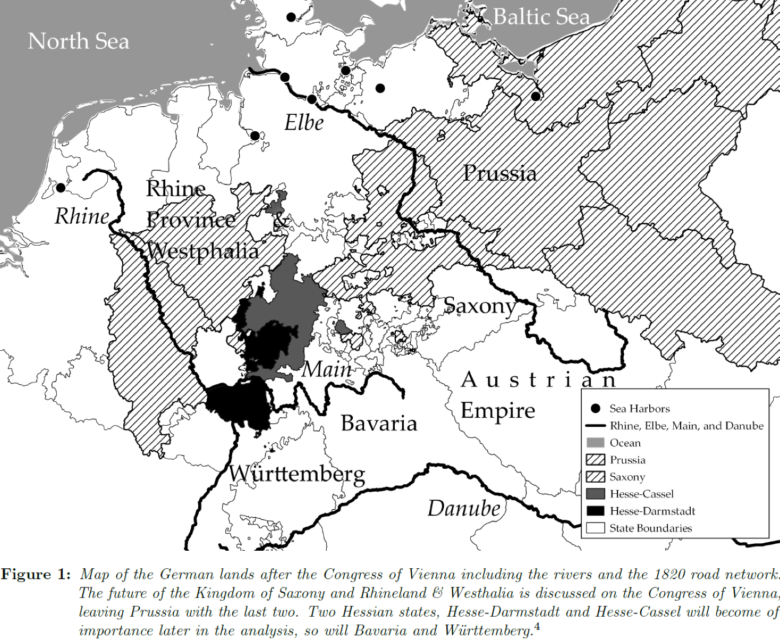

A major challenge to testing our idea empirically is that a state’s political boundaries (and hence its location) do not change very often, and if they do, the change is unlikely to be unrelated to trade or factor flows. However, the formation of the German Zollverein in 1834 can be considered as a quasi-experiment. Let us briefly revisit this historical episode. At the end of the Napoleonic wars of 1792-1814/15, only Russia and the UK were left as major military powers. Habsburg, Prussia, and the defeated France attempted to consolidate their positions at the expense of the many smaller states that had just about survived the wars, notably the former allies of Napoleon such as Saxony and Poland. Overall, the negotiations at the Congress of Vienna in 1814 were dominated by military-strategic considerations between the two great powers. Russia wanted to expand westwards, Prussia was desperate to annex the populous Kingdom of Saxony, which bordered Prussia in the south and would create a large and coherent territory. To this end, Prussia was willing to give up not only her Polish territories to Russia, but also her positions and claims on the Rhineland (Müller 1986). This met stiff resistance from Britain, joined by Habsburg and France, which feared a new Russian hegemony on the continent – the ‘Polish Saxon question’. After weeks of diplomatic struggle, the outcome was a division of Saxony, another division of Poland and Prussia being established as the “warden of the German gate against France” (Clapham 1921: 98). Figure 1 shows the result of these negotiations.

H/T to Continental Telegraph for the link.

March 10, 2019

Prussian Infantry under Frederick the Great

Military History Visualized

Published on 6 Oct 2017Prussian Infantry during the time of Frederick the Great of Prussia. Basic background on infantry types like Grenadiers, Fusiliers, etc., organization and combat formations.

»» SUPPORT MHV ««

» patreon – https://www.patreon.com/mhv

» paypal donation – https://www.paypal.com/cgi-bin/webscr…Military History Visualized provides a series of short narrative and visual presentations like documentaries based on academic literature or sometimes primary sources. Videos are intended as introduction to military history, but also contain a lot of details for history buffs. Since the aim is to keep the episodes short and comprehensive some details are often cut.

» SOURCES «

Guddat, Martin: Grenadiere, Musketiere, Füsiliere. Die Infanterie Friedrich des Großen

Fiedler, Siegfried: Taktik & Strategie der Kabinettskriege

Ortenburg, Georg: Waffen der Kabinettskriege

Militärgeschichtliches Forschungsamt: Friedrich der Große und das Militärwesen seiner Zeit. Vorträge zur Militärgeschichte. Band 8.

Chandler, David: The Art of War in the Age of Marlborough

Buchner, Alex: Handbuch der Infanterie 1939-1945

Bucher, Alex: Handbook on German Infantry 1939-1945

Haythornthwaite, Philip: Frederick the Great’s Army (2) – Infantry

Militärgeschichtliches Forschungsamt: Deutsche Militärgeschichte 1648-1939. Band 1.

Militärgeschichtliches Forschungsamt: Deutsche Militärgeschichte 1648-1939. Band 6.

Clark, Christopher: Iron Kingdom, The Rise and Downfall of Prussia 1600-1947

Guddat, Martin: Kürassiere, Dragoner, Husaren. Die Kavallerie Friedrichs des Großen.

Hawkins, Vincent B.: “Frederick the Great”, in: Brassey’s Encyclopedia of Military History and Biography, p. 339-345» DISCLAIMER «

Amazon Associates Program: “Bernhard Kast is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to amazon.com.”

Bernhard Kast ist Teilnehmer des Partnerprogramms von Amazon Europe S.à.r.l. und Partner des Werbeprogramms, das zur Bereitstellung eines Mediums für Websites konzipiert wurde, mittels dessen durch die Platzierung von Werbeanzeigen und Links zu amazon.de Werbekostenerstattung verdient werden können.

» TOOL CHAIN «

PowerPoint 2016, Word, Excel, Tile Mill, QGIS, Processing 3, Adobe Illustrator, Adobe Premiere, Adobe Audition, Adobe Photoshop, Adobe After Effects, Adobe Animate.

» CREDITS & SPECIAL THX «

Song: Ethan Meixsell – Demilitarized Zone

November 8, 2018

The Franco-Prussian War

Epic History

Published on 29 Dec 2015The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870 (19 July 1870 – 10 May 1871), was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the German states of the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. The conflict was caused by Prussian ambitions to extend German unification. Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck planned to provoke a French attack in order to draw the southern German states — Baden, Württemberg, Bavaria and Hesse-Darmstadt — into an alliance with the North German Confederation dominated by Prussia.

July 30, 2018

Pour Le Merite – Persia – Polish Legions I OUT OF THE TRENCHES

The Great War

Published on 28 Jul 2018Chair of Wisdom Time!

May 14, 2018

The Austro-Prussian War

Epic History

Published on 28 Dec 2015The Austro-Prussian War or Seven Weeks’ War (also known as the Unification War, Prussian–German War, German Civil War, or Fraternal War and in Germany as German War) was a war fought in 1866 between the German Confederation under the leadership of the Austrian Empire and its German allies on one side and the Kingdom of Prussia with its German allies and Italy on the other, that resulted in Prussian dominance over the German states.