Who is punished by tariffs on imported goods? Let’s go through the steps. The Canadian government imposes high tariffs on American dairy imports. That forces Canadians to pay higher prices for dairy products and protects Canada’s dairy producers from American competition. What should be the U.S. government’s response to Canada’s screwing its citizens? If you were in the Trump administration, you might retaliate by imposing stiff tariffs on softwood products built from pine, spruce and fir trees used by U.S. homebuilders. In other words, the U.S. should retaliate against Canada’s harming its citizens by forcing them to pay higher dairy product prices, by forcing Americans through tariffs to pay higher prices for wood and thereby raising the cost of building homes.

Walter E. Williams, “Economics Reality”, Townhall.com, 2020-02-04.

February 2, 2025

QotD: Tariffs

January 17, 2025

Trump’s demands include some things that would be quite beneficial to Canada

In the National Post, Bryan Schwartz suggests that some of the things Trump has raised as issues in Canada/US trade would be economically sensible for Canada to address because they’d reduce costs of doing business in Canada which would be good for all Canadians (except the crony capitalists in the blatantly protectionist “supply management” cartels):

US President-elect Donald Trump trolling about Canada becoming the 51st state of the union does seem to have directed attention to our bilateral trade situation wonderfully.

The threatened Trump tariffs would hurt both the United States and Canada in many ways. But the U.S., with a larger and more productive economy (on a per capita basis), is better able to sustain the immediate pain. The economic pressure on Canada is, therefore, serious and credible.

Canada should first address issues that are of particular importance to the Trump administration. The incoming president tends to emphasize national security, even over economic nationalism. The authority of the president, under the inherent powers of the office and congressional statutes, is greater if the issue relates to national security.

The same holds under international trade agreements. The president can raise issues that Canada can address in a prompt and reasonable manner. These include border security and increasing Canada’s commitment to contributing its fair share to international alliances, which would include increasing military expenditures.

Second, Canada should recognize that external pressures can provide opportunities to do things that are in this country’s own interests, but are otherwise politically difficult. Outside pressures have in the past encouraged Canada to adopt several measures that are good for the country, such as reducing pork-barreling and regional favouritism in government contracting.

Canada’s dairy protectionism provides a good example of a trade concession that would benefit Canada, as it is unfair to lower-income Canadians and, in the long run, hurts the industry itself. An industry more exposed to competitive pressures would be incentivized to be more productive and seek to expand into international markets.

Australia has shown how such marketing boards can be abolished in a manner that gives some time to the industry to adjust and ultimately benefits all concerned. Canada could similarly rid itself of its outdated and counterproductive Freshwater Fish Marketing Corporation, as well. To the extent that the United States pressures us to eliminate such supply management systems, it is actually doing us a favour.

Likewise, given that the U.S. is moving away from suppressing free expression in cyberspace, Canada would benefit from joining such initiatives rather than continuing down the path of having government or big companies effectively engage in censorship under the guise of fighting “disinformation”. The best remedy for any wrongheaded speech is rightheaded speech, not censorship.

At Dominion Review, Brian Graff steals a line from George C. Scott’s portrayal of Patton who said (in the film, not in real life) – “Rommel, you magnificent bastard. I read your book!” after reading the book of Trump’s Trade Representative, Robert Lighthizer:

Lighthizer wrote a book (released in June 2023) about his trade views and experience entitled No Trade Is Free: Changing Course, Taking on China, and Helping America’s Workers, which I just read. I only became aware of Lighthizer in November, in part because of a review of his book in The Guardian.

I don’t think Lighthizer is a bastard (literally or figuratively). He is hardly magnificent, but his book should be required reading for Canadians interested in our upcoming negotiations with the US. Our government would learn how best to counter the US by preparing a strong strategy and going on offence even before negotiations begin.

In short, we should not give away anything for free. This is Lighthizer’s position in matters of trade. For example, Canada should not volunteer to meet the two percent defense spending target ahead of negotiations. If anything, Canada should be accusing the US of whatever complaints we can muster. Trump might complain about the Canadian border being porous when it comes to people and drugs, but we can make the same claims, and add on the fact that the US should do more to stop the flow of illegal guns into Canada across our southern border.

Lighthizer provides a history of the US based around the idea that the US revolution and the constitution were a reaction to the mercantilist policies of Britain, which wanted to export manufactured goods and import only raw materials, while also limiting US trade with the rest of the world. Here is Lighthizer’s essential view:

Today, the tide has turned against the argument for unfettered free trade, in no small part because of the changes we made in the Trump administration. More broadly, evidence and experience have shown us that free trade is a unicorn – a figment of the Anglo-American imagination. No one really believes in it outside of countries in the Anglo-American world, and no one practices it. After the lessons of the past couple decades or so, few believe in it even within that world, save for some hard-core ideologues. It is a theory that never worked anywhere.

This is his critique of the neoliberal free trade approach:

According to the definitions preferred by these efficiency-minded free traders, the downside of trade for American producers is not evidence against their approach but rather is an unfortunate but necessary side effect. That’s because free trade is always taken as a given, not as an approach to be questioned. Rather than envisioning the type of society desired and then, in light of that conception of the common good, fashioning a trade policy to fit that vision, economists tend to do the opposite: they start from the proposition that free trade should reign and then argue that society should adapt. Most acknowledge that lowering trade barriers causes economic disruption, but very few suggest that the rules of trade should be calibrated to help society better manage those effects. On the right, libertarians deny that these bad effects are a problem, because the benefits of cheap consumer goods for the masses supposedly outweigh the costs, and factory workers, in their view, can be retrained to write computer programs. On the left, progressives promote trade adjustment assistance and other wealth-transfer schemes as a means of smoothing globalization’s rough edges.

This section is also key:

… mercantilism and a free market are dramatically different systems, with distinctions that are important to note. Mercantilism is a school of nationalistic political economy that emphasizes the role of government intervention, trade barriers, and export promotion in building a wealthy, powerful state. The term was popularized by Adam Smith, who described the policies of western European colonial powers as a “mercantile system.” Then and now, there are a vast array of tools available for countries seeking to go down this path. Mercantilist governments, for instance, frequently employ import substitution policies that support exports and discourage imports in order to accumulate wealth. They employ tariffs, too, of course, and they limit market access, employ licensing schemes, and use government procurement, subsidies, SOEs, and manipulation of regulation to favor domestic industries over foreign ones.

The focus of the book, and the main villain, is China, followed closely by the World Trade Organization (WTO). Canada gets less than 77 mentions, Mexico gets 99 mentions in the first 352 pages of 576 (the e-book stops counting at 99), and Japan gets 99 mentions in the first 400 pages. Compare this to China, which gets 99 mentions within the first 101 pages alone.

January 4, 2025

November 26, 2024

Crony Capitalist Canada – “Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre … has vowed to protect Big Dairy just like every other party leader”

In the National Post, Chris Selley discusses the latest attempt to further protect the outrageous profits our dairy companies make by overcharging Canadians for milk, butter, cheese, and other dairy products:

That unelected senators should not overrule the will of the House of Commons has always struck me as a rule most Canadians could agree on, whatever they think ought to happen with Canada’s upper chamber. Senators can propose amendments to bad bills, rake ministers over the coals at committee, call witnesses the House wasn’t interested in for whatever reason, raise red flags that haven’t yet been raised, all to the good. But gutting a bill, as the Senate has done with proposed legislation that would protect supply management in Canadian dairy, poultry and eggs even more than it’s already protected, is not kosher.

Not all violations of this policy are equally appalling, however. When the House of Commons is clearly not operating for the benefit of Canadians, when its focus demonstrably isn’t the public good but rather coddling and currying favour with special interests, it behooves the Senate to intervene as strenuously as possible while still at the end of the day respecting the lower chamber’s democratic legitimacy.

Coddling and currying favour is exactly what C-282, a private member’s bill from Bloc Québécois Luc Thériault, does: It proposes to make it illegal for a future government to lower the tariff rate for foreign products in supply-managed industries. You could call it the “no to cheaper groceries act.” Some senators wish to neuter it, such that it wouldn’t apply to any existing trade deals or deals already in negotiation. Bloc Leader Yves-François Blanchet had originally demanded the bill passed as one condition of keeping the Liberals afloat (although his deadline to do so has passed).

Fifty-one MPs of 338 opposed the pricey-groceries act at third reading. I would have said “only 51” except that’s a shocking number: 49 Conservatives and two Liberals, Nathaniel Erskine-Smith and Chandra Arya. It’s almost reason for hope … except of course that Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre voted for it, and has vowed to protect Big Dairy just like every other party leader. It goes without saying that Prime Minister Justin Trudeau not only supported it, but has come out against the Senate’s amendments.

“We will not accept any bill that minimizes or eliminates the House’s obligation to protect supply management in any future trade agreement,” Trudeau reassured Blanchet in the House on Wednesday. ” No matter what the Senate does, the will of the House is clear.”

I mean, what elected politician in Ottawa gives a shit about Canadians being gouged on grocery staples every week? They’d rather get the support of the milk, poultry and egg crony capitalists than help ordinary Canadians, and they’re terrified of being portrayed as anti-Quebec in an election year. Spineless cowards, the lot of them.

November 1, 2024

Canada – 30 protectionist marketing boards wrapped in a flag

In The Line, Greg Quinn points out just how blatantly hypocritical Canada’s politicians and diplomats are in any discussion with other nations when the subject turns to free trade:

Let me say this upfront, and clearly: when it comes to international trade, Canada is protectionist to an astonishing degree whilst at the same time claiming it is a supporter of global free trade. It wants every other country to open up (and complains when they don’t, or when they stand their ground) whilst ensuring access to the Canadian market is more difficult. This is a result of federal policy, inter-provincial restrictions, and vested interests. And it is flagrantly hypocritical.

When it comes to dairy, beef and the mutual recognition of professional qualifications, for example, Canada’s claim to openness is simply a lie. Agricultural groups and businesses dominate and control the local landscape and attempts to either overcome that (or bring external companies in) have failed on many occasions over the years. This could well get worse if the Liberals agree to what the Bloc Québécois has demanded — even more dairy protections — in a desperate attempt to remain in power for a little while longer.

Some of these issues are well known to Canadians — particularly the domestic ones, or the ones that touch on national unity frictions. But I’m not sure Canadians understand how this is perceived globally, including by Canada’s allies. Readers may recall that there was a mild furore a while back when the U.K. dared to pause trade negotiations as Canada refused to move on access for British cheese. There were accusations of the U.K. not playing fair and such like.

It’s bad enough that we “protect” Canadians from lower-priced foreign food, but we even manage to maintain inter-provincial trade barriers that directly harm all Canadian consumers:

Then we have interprovincial trade barriers. According to the Business Council of Alberta in a 2021 report, these barriers are tantamount to a 6.9 per cent tariff on Canadian goods. They also noted that removal of these could boost Canada’s GDP by some 3.8 per cent (or C$80 billion), increase average wages by some C$1,800 per person, and increase government revenues for social programming by some 4.4 per cent.These barriers hinder internal trade between the provinces, including the work of those companies that import goods from other countries.

A freer market, at home or globally, would not solve all the issues that exist with prices, but it would certainly increase competition and give consumers more choice. What exists at the minute is a pretense of choice.

Opening up the Canadian market would certainly benefit other countries, including my own United Kingdom, and there would be some impact on local business and producers. This is true, and acknowledged. But opening itself up to more global trade and dismantling internal trade barriers — and these are things all the politicians insist they like the sound of in theory — would be a win-win for Canadian consumers and Canadian society as a whole. Some big companies and carefully coddled special interests would be upset, but they aren’t supposed to be the ones making decisions in a democracy, or in a free market.

October 10, 2024

Trump’s tariff proposals will rival Smoot-Hawley for self-inflicted economic woes

J.D. Tuccille explains why Trump’s economic plans are very much a curate’s egg of good and bad ideas, but the proposed tariff plans would more than compensate for any good positive effects from the rest of his proposals:

Willis C. Hawley (left) and Reed Smoot in April 1929, shortly before the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act passed the House of Representatives.

Library of Congress photo via Wikipedia Commons.

Former president and current Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump wants to extend the tax cuts passed when he was in the White House, which are due to expire next year. That would not just be welcomed by the many Americans who would benefit, it could boost economic activity. But there’s a big problem: The protectionist tariffs favored by Trump would undo the good done by his tax cuts, reducing rather than increasing prosperity.

Tariffs Not Seen Since the Great Depression

“Former President Donald Trump’s proposals to impose a universal tariff of 20 percent and an additional tariff on Chinese imports of at least 60 percent would spike the average tariff rate on all imports to highs not seen since the Great Depression,” warns Erica York of the Tax Foundation.

Trump has actually been a little vague on the size of his universal tariff, first floating it at 10 percent while allowing “it may be more than that”, and then upping the ante to 20 percent. Either way, it’s a cost that ends up being largely paid by Americans in terms of higher retail prices and more expensive imported parts and materials for domestic manufacturing.

The Trump administration’s 2018 “tariffs resulted in higher prices for a wide variety of goods that U.S. consumers and businesses purchase,” the Tax Foundation’s Alex Durante and Alex Muresianu concluded.

Even when tariffs don’t directly affect the cost of imported goods purchased by consumers, they still drive up the prices of many things made in the U.S. The Cato Institute’s Pierre Lemieux points out that “a tariff on an input (say, steel) is paid by the American importer who will typically pass it down the supply chain to his customers and eventually to the consumers of the final good (say, a car)”. Instead of boosting domestic production, that can do harm, instead.

“For manufacturing employment, a small boost from the import protection effect of tariffs is more than offset by larger drags from the effects of rising input costs and retaliatory tariffs,” Federal Reserve Board economists found when they researched the 2018 tariffs.

That’s not to say Trump is alone in his protectionism. Last month, Bob Davis noted for Foreign Policy that “the Biden administration is the first since at least President John F. Kennedy’s time to fail to negotiate a major free trade deal, instead embracing tariffs” while Trump pursued both tariffs and trade deals.

August 28, 2024

H.R. McMaster dishes on Trump’s first term in office

In Reason, Liz Wolfe covers some of the head-scratchers former National Security Advisor H.R. McMaster revealed about working for Donald Trump:

Donald Trump addresses a rally in Nashville, TN in March 2017.

Photo released by the Office of the President of the United States via Wikimedia Commons.

What might a second Trump White House be like? In his new book, At War with Ourselves: My Tour of Duty in the Trump White House, Lt. Gen. H.R. McMaster, who served as national security adviser to Donald Trump (for one year), characterizes Oval Office meetings as “exercises in competitive sycophancy” where advisers would greet him with lines like “your instincts are always right” or “no one has ever been treated so badly by the press”.

Trump, meanwhile, would come up with crazy concepts, and float them: “Why don’t we just bomb the drugs?” (Also: “Why don’t we take out the whole North Korean Army during one of their parades?”)

This is one man’s account, of course. McMaster’s word should not be taken as gospel, and some of his frustration might stem from his dismissal, or his foreign-policy prescriptions being at times ignored by his boss. But it’s a somewhat revealing look behind the curtain at policy-setting in a White House helmed by an especially mercurial commander in chief, who “enjoyed and contributed to interpersonal drama in the White House and across the administration”.

It also shows how quickly Trump fantasies have percolated through the Republican Party, namely the “let’s just bomb Mexico to get rid of the cartels” line, which Trump has been toying with since roughly 2019 (or possibly more like 2017, after he chatted with Rodrigo Duterte, former president of the Philippines, who had promised to kill 100,000 drug traffickers during his first six months as president). A few years prior, in 2015, he had suggested that Mexico was sending rapist and drug-traffickers across the southern border, and that we’d need to build a wall between the two countries, but it wasn’t until nine American citizens were killed in Mexico that Trump trotted out the idea of declaring cartels foreign terrorist organizations and using military might to eradicate them.

Trump’s line from 2019 has now become standard fare, notes The Economist: The Republican primary debates included lots of tough talk on Mexico, specifically on the bombing front, with Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis claiming he’d send special forces down there on Day One. Right-wing think tanks have embraced the messaging, with articles headlined “It’s Time to Wage War on Transnational Drug Cartels”. Taking cues from other members of her party, Georgia Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene asked why “we’re fighting a war in Ukraine, and we’re not bombing the Mexican cartels”. Whether it’s economic protectionism (10 percent across-the-board tariffs, with 60 percent tariffs imposed on Chinese imports) or Mexico-bombing, Trump has near-magical abilities to get other members of his party to accept something previously regarded as absurd.

July 25, 2024

David Friedman on the economics of trade

David Friedman discusses how, for example, the US and China manage their trading relationship:

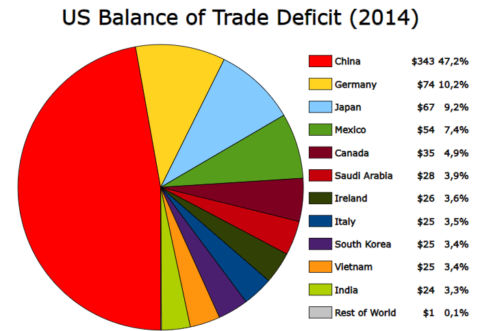

“United States Balance of Trade Deficit-pie chart” by Shirishag75 is marked with CC0 1.0 .

I recently read a thread about US/China trade on a forum occupied mostly by intelligent people. As best I could tell, all participants were taking it for granted that things that make it more expensive to produce in the US, such as regulations or minimum wage laws, make the US “less competitive”, increase the trade deficit, give the Chinese an advantage. Reading Project 2025, the Heritage Foundation’s battle plan for a future conservative president, I observed the same pattern, with only one exception.

It did not seem to have occurred to any of the forum posters that US costs are in dollars, Chinese costs in Yuan, and what determines the exchange rate between them is the cost of producing things. Discussing trade policy in terms of absolute advantage, pre-Ricardian economics, isn’t quite as bad as discussing the space program on the assumption that the Earth is at the center of the universe with sun, moon and planets embedded in a set of nested crystalline spheres surrounding it — Copernicus was about three centuries earlier than Ricardo — but it is close. It is a point that I made here about a year ago, but since the question came up in my most recent post and in a thread on my favorite forum, it is probably worth making again.

The Economics of Trade

It is easiest to start with the simple case of two countries and no capital flows. The only reason Americans want to buy yuan with dollars is to buy Chinese goods, the only reason Chinese want to sell yuan for dollars is to buy American goods. If Americans try to buy more yuan than Chinese want to sell, the price of yuan in dollars goes up, if Chinese want to sell more yuan than Americans want to buy, the price goes down, just as in other markets. The price of yuan in dollars, the exchange rate, ends up at the price at which supply equals demand, which means that Americans are importing the same dollar (and yuan) value of goods that they are exporting.

Suppose the US government, inspired by the mercantilist view that countries get rich by exporting more than they import, tries to produce a “favorable” balance of trade by imposing a tariff on Chinese imports. Chinese goods are now more expensive to Americans. Since they want to buy less from China they don’t need as many yuan so the demand for yuan goes down, the price of yuan in dollars goes down, which reduces the cost of Chinese goods to Americans. Just as before, the exchange rate ends up at a level at which the dollar value of US exports equals the dollar value of US imports. Both imports and exports are now less, since trade is being taxed, but the balance of trade is exactly what it would be without the tariff.

Suppose the US becomes less good at making things due to an increase in government regulation or some other cause. Dollar prices of US goods in the US go up. That makes US goods more expensive to Chinese purchasers so they buy fewer of them, decreasing the demand for dollars on the dollar/yuan market. The exchange rate shifts — dollars are now less valuable so their price falls. Trade still balances. The US is not “less competitive”, merely poorer.

Now add in more countries. One reason Chinese want to buy dollars is to sell them to Germans who want dollars with which to buy American goods. We end up with a trade deficit with China, since some of the dollars they get for their exports are being used to import goods from Germany instead of the US, but a matching trade surplus with Germany, since they are using both the dollars they get by selling things to us and the dollars they get from China to buy goods from us. The same logic applies with more countries.

To explain how it is possible for the US to have a trade deficit we now drop the assumption of no capital movements. One reason Chinese want dollars is to buy goods and ship them to China but another is to buy assets in America — government bonds, shares of stock, real estate. Dollars bought and dollars sold are still equal but exports of goods no longer equal imports of goods. Part of what the US is “exporting”, selling to foreigners, is assets located in the US.

Suppose the US government wants to reduce the trade deficit. One way would be to reduce the budget deficit, since if the US is borrowing less it will not have to pay lenders as high an interest rate, which will make US bonds less attractive to Chinese buyers. Another way would be to block capital movements, make it illegal for foreign buyers to buy US assets. Doing that, however, means less capital investment in the US, hence higher interest rates. With fewer lenders to buy US bonds, the government will have to offer a higher interest rate to sell them.

One argument sometimes offered for restricting foreign investment is that if the Chinese own a lot of US assets that gives them power over us. The same argument was offered in the early 19th century when European investors were paying to build railroads and dig canals in the US. Daniel Webster pointed out that, if there was a conflict with European powers, their assets were sitting on our territory under our control. It wasn’t like they could repossess the Erie canal.

What about imposing a tariff in order to reduce imports? The logic of the previous argument still applies — the exchange rate will shift to make imports more attractive, exports less. Any effect on the deficit will depend on what happens to the attractiveness of US assets to Chinese investors. Figuring out the net effect is complicated, depending in part on what people expect trade policy and exchange rates to be when they collect on their capital investments.

April 16, 2024

QotD: Binding and non-binding rules

Describing situations in which violating a sound rule will make the world a better place is surprisingly easy. The reason for this ease is that the very purpose of rules – “the reason of rules” – is that they are tools to better enable us always-imperfectly informed human beings to successfully navigate a world filled with uncertainty. All that such descriptions require is the assumption that we human beings know more than we know.

An omniscient being would be foolish to bind itself to rules.

When we adopt a rule, we wisely admit our ignorance. For a clever assistant professor or ambitious politician to then describe situations in which violating this or that rule will make the world a better place is to achieve absolutely nothing. Although such descriptions often appear to be ingenious discoveries of means for improving the human condition, such descriptions are nearly always nothing but trite demonstrations that if we knew what we do not and cannot know, then acting in disregard of the rule would bring about a state of affairs better than the state of affairs that would be brought about by following the rule.

Well duh.

As a rule, whenever you encounter someone peddling a scheme for improving the world by giving the state discretion to act in violation of well-established rules – for example, to make workers better off by blocking the operation of the price system with minimum wages, or to enrich residents of the domestic economy by substituting free trade with “strategic trade policies” or “optimal tariffs” – recognize that these scheme peddlers arrogantly assume that they or those who will carry out their schemes possess knowledge and information that human beings, as a rule, do not and cannot possibly ever possess.

Don Boudreaux, “Quotation of the Day…”, Café Hayek, 2019-08-20.

April 11, 2024

All the ways A few of the ways Canada is broken

In The Line, Andrew Potter outlines some of the major political and economic pressures that prompted the formation of the Dominion of Canada in 1867, then gets into all the ways some of the myriad ways that Canada is failing badly:

It is useful to remember all this, if only to appreciate the extent to which Canada has drifted from its founding ambitions. Today, there are significant interprovincial barriers to trade in goods and services, which add an estimated average of seven per cent to the cost of goods. Not only does Canada not have a free internal market in any meaningful sense, but the problem is getting worse, not better. This is in part thanks to the Supreme Court of Canada which continues its habit of giving preposterously narrow interpretations to the clear and unambiguous language in the constitution regarding trade so as to favour the provinces and their protectionist instincts.

On the defence and security front, what is there to say that hasn’t been said a thousand times before. From the state of the military to our commitments to NATO to the defence and protection of our coasts and the Arctic to shouldering our burden in the defence of North America, our response has been to shrug and assume that it doesn’t matter, that there’s no threat, or if there is, that someone else will take care of it for us. We live in a fireproof house, far from the flames, fa la la la la. Monday’s announcement was interesting, but even if fully enacted — a huge if — we will still be a long way from a military that can meet both domestic and international obligations, and still a long way from the two per cent target.

As for politics, only the most delusional observer would pretend that this is even remotely a properly functioning federation. Quebec has for many purposes effectively seceded, and Alberta has been patiently taking notes. Saskatchewan is openly defying the law in refusing to pay the federal carbon tax. Parliament is a dysfunctional and largely pointless clown show. No one is happy, and the federal government is in some quarters bordering on illegitimacy.

All of this is going on while the conditions that motivated Confederation in the first place are reasserting themselves. Global free trade is starting to go in reverse, as states shrink back from the openness that marked the great period of liberalization from the early 1990s to the mid 2010s. The international order is becoming less stable and more dangerous, as the norms and institutions that dominated the post-war order in the second half of the 20th century collapse into obsolescence. And it is no longer clear that we will be able to rely upon the old failsafe, the goodwill and indulgence of the United States. Donald Trump has made it clear he doesn’t have much time for Canada’s pieties on either trade or defence, and he’s going to be gunning for us when he is returned to the presidency later this year.

Ottawa’s response to all of this has been to largely pretend it isn’t happening. Instead, it insists on trying to impose itself on areas of provincial jurisdiction, resulting in a number of ineffective programs — dentistry, pharmacare, daycare, and now, apparently, school lunches — that are anything but national, and which will do little more than annoy the provinces while creating more bureaucracy. Meanwhile, the real problems in areas of clear federal jurisdiction just keep piling up, but the money’s all been spent, so, shrug emoji.

What to do? We could just keep going along like this, and follow the slow-mo train wreck that is Canada to its inevitable end. That is is the most likely scenario.

February 25, 2024

Canadian publishing “has been decimated since Ottawa took an active interest in it and while federal policies haven’t been the whole problem, they’ve been vigorous contributors”

In the latest SHuSH newsletter, Ken Whyte contrasts the wholesome intentions of the Canadian federal government on cultural issues with the gruesome reality over which they’ve presided:

Even James Moore, [Liberal cabinet minister Melanie] Joly’s Conservative predecessor in the heritage department, applauded her initiative as good and necessary, although he warned it wouldn’t be easy. Moore had wanted to do the job himself, but his boss, Stephen Harper, didn’t want to waste political capital on fights with the arts community. He told Moore his job in the heritage department was to sit on the lid.

Joly got off to a promising start, only to have her entire initiative scuppered by a rump of reactionary Quebec cultural commentators outraged at her willingness to deal with a global platform like Netflix without imposing on it the same Canadian content rules that Ottawa has traditionally applied to radio and television networks. Liberal governments live and die by their support in Quebec and can’t afford to be offside with its cultural community. Joly was shuffled down the hall to the ministry of tourism.

She has been succeeded by four Liberal heritage ministers in five years: Pablo Rodriquez, Steven Guilbeault, Pablo Rodriguez II, and Pascale St-Onge. Each has been from Quebec and each has been paid upwards of $250,000 a year to do nothing but sit on the lid.

The system remains broken. We’ve discussed many times here how federal support was supposed to foster a Canadian-owned book publishing sector yet led instead to one in which Canadian-owned publishers represent less than 5 percent of book sales in Canada. The industry has been decimated since Ottawa took an active interest in it and while federal policies haven’t been the whole problem, they’ve been vigorous contributors.

Canada’s flagship cultural institution, the CBC, is floundering. It spends the biggest chunk of its budget on its English-language television service, which has seen its share of prime-time viewing drop from 7.6 percent to 4.4 percent since 2018. In other words, CBC TV has dropped almost 40 percent of its audience since the Trudeau government topped up its budget by $150 million back in the Joly era. If Pierre Poilievre gets elected and is serious about doing the CBC harm, as he’s threatened since winning the Conservative leadership two years ago, his best move would be to give it another $150 million.

The Canadian magazine industry is kaput. Despite prodigious spending to prop up legacy newspaper companies, the number of jobs in Canadian journalism continues to plummet. The Canadian feature film industry has been moribund for the last decade. Private broadcast radio and television are in decline. There are more jobs in Canadian film and TV, but only because our cheap dollar and generous public subsidies have convinced US and international creators to outsource production work up here. It’s certainly not because we’re producing good Canadian shows.

[…]

When the Trudeau government was elected in 2015, it posed as a saviour of the arts after years of Harper’s neglect and budget cuts. It did spend on arts and culture during the pandemic — it spent on everything during the pandemic — but it will be leaving the cultural sector in worse shape than it found it, presuming the Trudeau Liberals are voted out in 2025. By the government’s own projections, Heritage Canada will spend $1.5 billion in 2025-26, exactly what it spent in Harper’s last year, when the population of Canada was 10 percent smaller than it is now.

That might have been enough money if the Liberals had cleaned up the system. Instead, they’ve passed legislation that promises more breakage than ever. Rather than accept Joly’s challenge and update arts-and-culture funding and regulations for the twenty-first century, the Trudeau government did the opposite. Cheered on by the regressive lobby in Quebec, it passed an online news act (C-18) and an online streaming act (C-11) that apply old-fashioned protectionist policies to the whole damn Internet.

This comes on top of the Liberals transforming major cultural entities, including the CBC and our main granting bodies, The Canada Council and the Canada Book Fund, into Quebec vote-farming operations. The CBC spends $99.5 per capita on its French-language services (there are 8.2 million Franco-Canadians) and $38 per capita on Canadians who speak English as the first official language. The Canada Council spends $16 per capita in Quebec; it spends $10.50 per capita in the rest of Canada. The Canada Book Fund distributes $2 per capita in Quebec compared to $.50 per capita in the rest of the country. Even if one believes that a minority language is due more consideration than a majority language, these numbers are ridiculous. They’re not supporting a language group; they’re protecting the Liberal party.

February 20, 2024

QotD: Tariffs and protectionism

The economic case against protectionism is practically invincible. While theoretical curiosities can be described in which an import tariff (or an export subsidy) yields to the people of the home country net economic gains, the conditions that must prevail for these possibilities to have practical merit are absurdly unrealistic.

Yet in their efforts to justify punitive taxes on fellow citizens’ purchases of imports, protectionists regularly trot out these theoretical curiosities. And none is more frequently paraded in public than is the assertion that high tariffs imposed by the home government today will pressure foreign governments to lower their tariffs tomorrow, with the final result being freer trade worldwide.

“Our tariffs are the best means for making trade freer and bringing about what Adam Smith and all free traders have desired: maximum possible expansion of the international division of labor!” protectionists declare with straight faces.

This protectionist apology for tariffs is as believable as is the apology often offered by today’s campus radicals for speech codes and the harassment of certain speakers: “Our insistence on silencing conservatives and libertarians is actually a means of promoting campus diversity and inclusion!”

Both declarations are Orwellian.

Don Boudreaux, “Is Trump’s Ultimate Goal Global Free Trade?”, Catallaxy Files, 2019-06-11.

September 20, 2023

How the feds could lower grocery prices without browbeating CEOs

Jesse Kline has some advice for Prime Minister Jagmeet Singh Justin Trudeau on things his government could easily do to lower retail prices Canadians face on their trips to the grocery store:

CBC report on federal scapegoating of grocery chain CEOs.

https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/government-grocery-store-meeting-ottawa-food-prices-1.6967978

What exactly the grocery executives are supposed to do to bring down prices that are largely out of their control is anyone’s guess. Do they decrease their profit margins even further, thereby driving independent retailers out of business and shedding jobs by increasing their reliance on automation? Do they stop selling high-priced name-brand products, thus decreasing their average prices while driving up profits through the sale of house-brand products?

If the government were serious about working with grocers, rather than casting them as villains in a piece of performative policy theatre, here are a number of policies the supermarket CEOs should propose that would have a meaningful effect on food prices throughout the country.

End supply management

Why do Canadians pay an average of $2.81 for a litre of milk — among the highest in the world — when our neighbours to the south can fill their cereal bowls for half the cost? Because a government-mandated cartel controls the production of dairy products in this country, while the state limits foreign competition through exorbitantly high tariffs on imports.The same, of course, is true of our egg and poultry industries. Altogether, it’s estimated that supply managements adds between $426 and $697 a year to the average Canadian household’s grocery bill. It’s not a direct cause of inflation, but it’s a policy that, if done away with, could save Canadians up to $700 a year in fairly short order.

Yet not only have politicians been unwilling to address it, they have been fighting some of our closest trading partners to ensure that foreign food products don’t enter the Canadian market and drive down prices. Ditching supply management would be a no-brainer, if anyone in Ottawa was willing to use their brain.

Reduce regulations

The best way to decrease prices in any market is to foster competition. As the Competition Bureau noted in a report released in June, “Canada’s grocery industry is concentrated” and “tough to break into”. Worse still, “In recent years, industry concentration has increased”.So why don’t more foreign discount grocery chains set up shop here? Perhaps it’s because they know our national policy encourages Canadian-owned oligopolies. While grocery retailers don’t face the same foreign-ownership restrictions as airlines or telecoms, the products they sell are heavily regulated, which acts as a barrier to bringing in cheaper goods from other countries.

Although it wasn’t the primary reason for the lack of foreign competition, the Competition Bureau did note that, “Laws requiring bilingual labels on packaged foods can be a difficult additional cost for international grocers to take on”.

Other ways the federal government could help Canadians afford their grocery bills include:

- Jail thieves

- Stop port strikes

- Don’t tax beer

- Axe the carbon tax

Don’t hold your breath for any of these ideas to be taken up by Trudeau’s Liberals.

September 17, 2023

Why Indigo’s struggles are far from over

Following up from last week, in this week’s SHuSH newsletter Ken Whyte explains why Indigo went in the direction it chose and why it seemed like the thing to do at that time:

“Indigo Books and Music” by Open Grid Scheduler / Grid Engine is licensed under CC0 1.0

Bookselling is a difficult business and it’s been especially difficult over the last twenty years. The Internet captured a lot of the used book business and shifted it online. Amazon captured a lot of the new book business and shifted it online (and bought Abebooks.com, one of the largest used book sites).

Former Indigo CEO Heather Reisman tried and failed to convince the federal government to keep Amazon south of the border back around 2002. She went so far as to sue the feds on the grounds that Amazon, as a cultural entity, was not majority-owned by Canadians and therefore operating in contravention of the Investment Canada Act. The suit went nowhere because Amazon then had no physical presence in Canada; it operated primarily through Canada Post. By the time Amazon did announce its intention to build a warehouse north of the border, early in 2010, the government had given up enforcing the Investment Canada Act. It was happy to have Amazon create new jobs.

It was when Amazon opened its Canadian warehouse that Heather began backing Indigo out of the book business. She cursed Amazon for its anticompetitive practices, not least its habit of selling books below cost to destroy competitors, and adopted the term “cultural department store” as a pivot from bookstores.

I’ve made it clear in newsletter after newsletter that I don’t like the direction Heather took Indigo but it’s only fair to look back at prevailing circumstances in 2010 and wonder if she really had a choice.

I’m sure she had stacks of research and hordes of people telling her that abandoning books was the only move. Attempting to compete with Amazon’s enormous scale and superior logistics would have struck many as a fool’s errand. Amazon would always have the largest selection, the best price, and the fastest delivery.

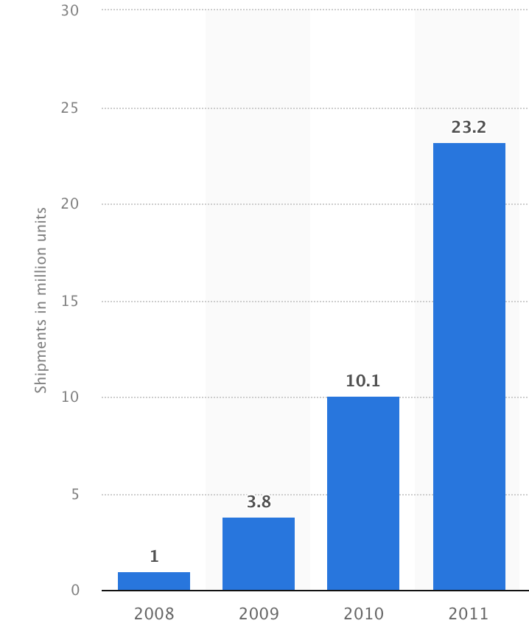

There was also a widespread belief that print was dead. E-books, e-readers, and tablets were the future, along with the “one very, very, very large single text“. Global e-reader sales were growing like this:

They were expected to keep growing. So were sales of e-books. In 2012, the Financial Post quoted data from Indigo predicting that e-books would capture 50 percent of the market in five years.

So, having played the Canadian Nationalist card and discovering that the government was willing to bluster but not to meaningfully act, Heather Reisman took the advice of her consultants and diversified away from books and into all the utter crap that currently befoul at least half of the retail space in every Indigo store. After all, the big box bookstores in the United States were clearly failing in the face of Amazon, with Borders filing for bankruptcy and Barnes & Noble staggering in the same direction. From 1999 to 2019, fully half of all the bookstores in the country disappeared.

The story isn’t as bleak as it looked in 2019, as Barnes & Noble is staging quite a comeback by concentrating on the book business. It’s a radical move, but Indigo could do far worse than cooking up a maple-flavoured version of the Barnes & Noble strategy. It might fail, but they’ll definitely fail if they keep on pretending to be a department gift store that also has a few books.

August 29, 2023

The noble reasons New Jersey banned self-service gas stations

Of course, by “noble reasons” I mean “corrupt crony capitalist reasons“:

“Model A Ford in front of Gilmore’s historic Shell gas station” by Corvair Owner is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

New Jersey’s law, like Oregon’s, ostensibly stemmed from safety concerns. In 1949, the state passed the Retail Gasoline Dispensing Safety Act and Regulations, a law that was updated in 2016, which cited “fire hazards directly associated with dispensing fuel” as justification for its ban.

If the idea that Americans and filling stations would be bursting into flames without state officials protecting us from pumping gas sounds silly to you, it should. In fact, safety was not the actual reason for New Jersey’s ban (any more than Oregon’s ban was, though the state cited “increased risk of crime and the increased risk of personal injury resulting from slipping on slick surfaces” as justification).

To understand the actual reason states banned filling stations, look to the life of Irving Reingold (1921-2017), a maverick entrepreneur and workaholic who liked to fly his collection of vintage World War II planes in his spare time. Reingold created a gasoline crisis in the Garden State, in the words of New Jersey writer Paul Mulshine, “by doing something gas station owners hated: He lowered prices”.

In the late 1940s, gasoline was selling for about 22 cents a gallon in New Jersey. Reingold figured out a way to undercut the local gasoline station owners who had entered into a “gentlemen’s agreement” to maintain the current price. He’d allow customers to pump gas themselves.

“Reingold decided to offer the consumer a choice by opening up a 24-pump gas station on Route 17 in Hackensack,” writes Mulshine. “He offered gas at 18.9 cents a gallon. The only requirement was that drivers pump it themselves. They didn’t mind. They lined up for blocks.”

Consumers loved this bit of creative destruction introduced by Reingold. His competition was less thrilled. They decided to stop him — by shooting up his gas station. Reingold responded by installing bulletproof glass.

“So the retailers looked for a softer target — the Statehouse,” Mulshine writes. “The Gasoline Retailers Association prevailed upon its pals in the Legislature to push through a bill banning self-serve gas. The pretext was safety …”

The true purpose of New Jersey’s law had nothing to do with safety or “the common good”. It was old-fashioned cronyism, protectionism via the age-old bootleggers and Baptists grift.

Politicians helped the Gasoline Retailers Association drive Reingold out of business. He and consumers are the losers of the story, yet it remains a wonderful case study in public choice theory economics.

The economist James M. Buchanan received a Nobel Prize for his pioneering work that demonstrated a simple idea: Public officials tend to arrive at decisions based on self-interest and incentives, just like everyone else.