[Bertie Wooster, who has a terrible hangover, encounters a prospective new valet – Jeeves.]

“If you would drink this, sir,” he said, with a kind of bedside manner, rather like the royal doctor shooting the bracer into a sick prince. “It’s a little preparation of my own invention. It is the Worcestershire sauce that gives it its colour. The raw egg makes it nutritious. The red pepper gives it bite. Gentlemen have told me they have found it extremely invigorating after a late evening.”

I would have clutched at anything that looked like a lifeline that morning. I swallowed the stuff. For a moment I felt as if someone had touched off a bomb inside the old bean and was strolling down my throat with a lighted torch, and then everything seemed suddenly to get all right. The sun shone in through the treetops and, generally speaking, hope dawned once more.

“You’re engaged!” I said, as soon as I could say anything.

P.G. Wodehouse Carry on, Jeeves (1925).

April 1, 2025

QotD: Jeeves proves his talent for the first time

August 25, 2024

QotD: P.G. Wodehouse’s unique way to get letters delivered

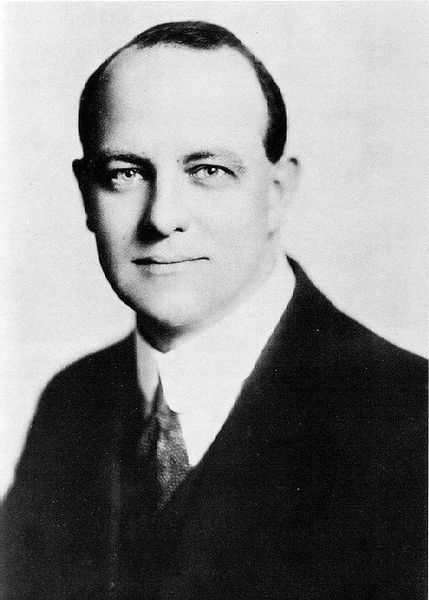

In previous columns […] I wrote about Homage to PG Wodehouse, a 1973 tribute edited by Thelma Cazalet-Keir, sister-in-law of Wodehouse’s beloved stepdaughter Leonora. My final extracts begin with an account by the American Guy Bolton (1884-1979), who collaborated with the Master on no fewer than 21 musical comedies for the stage and became his lifelong friend. In one of my favourite anecdotes, he describes how he called on Wodehouse in London in the mid-1920s.

“He was living in bachelor quarters in a tall, old-fashioned building in Queen’s Gate. His flat was on the fifth floor. There was no lift. I was travel tired and I toiled up the long staircase, pausing on the landings to pant. I found his door ajar and, entering, I found him writing a letter. He greeted me with a cheery ‘Hurrah, you’re here!’ and added, ‘Just a tick and I’ll get this letter off.’

“He shoved the letter in an envelope, stuck a stamp on it, then went over to the half-open window and tossed it out. ‘What on earth?’ I asked. ‘Has the joy of seeing me brought on some sort of mental lapse? That was your letter you just threw out of the window.’ ‘I know that. I can’t be bothered to go toiling down five flights every time I write a letter.’ ‘You depend on someone picking it up and posting it for you?’ ‘Isn’t that what you would do if you found a letter stamped and addressed lying on the pavement? All I can say is it works.’ ‘Well I wish you’d write me a letter while I’m here in London. I’d like to show it round in America – a bit of a score for good old England’.”

Bolton goes on: “It was the second day after moving into a fourth-floor flat in South Audley Street when my doorbell rang and I opened it to a rather stout individual somewhat out of breath. ‘Are you Mr Bolton? I have a letter for you.’ The envelope was in Plum’s handwriting.

“He said he was a taxi driver but refused a tip, accepting instead a bottle of Guinness. While he was drinking it, I phoned Plum. ‘I have your letter,’ I said. ‘What?’ said Plum in a slightly awed voice. ‘I only threw it out of the window 20 minutes ago.’ ‘You were right,’ I said. ‘It’s by far the quickest way to send a letter to a friend in London.’ ‘Yes, indeed. The GPO had better look to their laurels and keep an eye on their laburnums’.”

Of his friend, Bolton says: “He has one quality that is rare in our age. It is innocence. It carries with it a trusting belief in the goodness of heart of his fellow men. Suspicion and distrust have no place in his nature. The characters in his books share in it – even his villains are likely to succumb before a finger shaken by one of those bright-eyed, no-nonsense Wodehouse heroines.”

Alan Ashworth, “That reminds me: A final homage to Wodehouse”, The Conservative Woman, 2024-05-21.

May 2, 2024

When Malcolm Muggeridge investigated P.G. Wodehouse for MI6

Alan Ashworth explains the circumstances under which the great P.G. Wodehouse became the subject of an MI6 (Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service) treason investigation near the end of the Second World War:

[Malcolm Muggeridge:] “I first made Wodehouse’s acquaintance in circumstances which might have been expected to shake even his equanimity. This was in Paris just after the withdrawal of the German occupation forces. As Wodehouse well understood, the matter of his five broadcasts from Berlin would now have to be explained; and in the atmosphere of hysteria that war inevitably generates, the consequences might be very serious indeed. It would have been natural for him to be shaken, pale, nervous; on the contrary I found him calm and cheerful. I thought then, and think now more forcibly than ever, that this was due not so much to a clear conscience as to a state of innocence which mysteriously has survived in him.”

Muggeridge explains that he was attached to an MI6 contingent and a colleague “mentioned to me casually that he had received a short list of so-called traitors who cases needed to be investigated, one of the names being PG Wodehouse”. Muggeridge readily agreed to take on the case, “partly out of curiosity and partly from a feeling that no one who had made as elegant and original a contribution to the general gaiety of living should be allowed to get caught up in the larger buffooneries of war”. He duly visited Wodehouse at his hotel that same evening and the author described what had happened to him from the collapse in 1940 of France, where he was living with his wife Ethel, to his internment at a former lunatic asylum in Tost, Poland.

“The normal wartime procedure is to release civilian internees when they are sixty. Wodehouse was released some months before his sixtieth birthday as a result of well-meant representations by American friends – some resident in Berlin, America not being then at war with Germany. He made for Berlin, where his wife was awaiting him. The Berlin representative of the Columbia Broadcasting System asked him if he would like to broadcast to his American readers about his internment and foolishly he agreed, not realising the broadcasts would have to go over the German network and were bound to be exploited in the interest of Nazi propaganda.” [Here are German transcripts of the offending items.]

Muggeridge goes on: “It has been alleged that there was a bargain whereby Wodehouse agreed to broadcast in return for being released from Tost. This has frequently been denied and is, in fact, quite untrue but nonetheless still widely believed.”

Wodehouse came under virulent attack, particularly from Cassandra, the Daily Mirror columnist William Connor, who denounced him as a traitor to his country. Public libraries banned his books. Wodehouse wrote to the Home Secretary admitting he had been “criminally foolish” but said the broadcasts were “purely comic” and designed to show Americans a group of interned Englishmen keeping up their spirits. But the damage was done and the stigma stuck. After the war he spent the rest of his life in America.

In words that resonate half a century after their publication, Muggeridge says: “Lies, particularly in an age of mass communication, have much greater staying power than the truth.

“In the broadcasts there is not one phrase or word which can possibly be regarded as treasonable. Ironically enough, they were subsequently used at an American political warfare school as an example of how anti-German propaganda could subtly be put across by a skilful writer in the form of seemingly innocuous, light-hearted descriptive material. The fact is that Wodehouse is ill-fitted to live in an age of ideological conflict. He just does not react to human beings in that sort of way and never seems to hate anyone – not even old friends who turned on him. Of the various indignities heaped upon him at the time of his disgrace, the only one he really grieved over was being expunged from some alleged roll of honour at his old school, Dulwich.”

[…]

Muggeridge records that, when the war ended, the Wodehouses left France for America. “Ethel has been back to England several times but Wodehouse never, though he is always theoretically planning to come. I doubt if he ever will [he didn’t, dying in 1975 at the age of 93]. His attitude is like that of a man who has parted, in painful circumstances, from someone he loves and whom he both longs for and dreads to see again.”

February 2, 2024

Perhaps something for Wodehouse fans who want a bit more sex and violence in their fiction

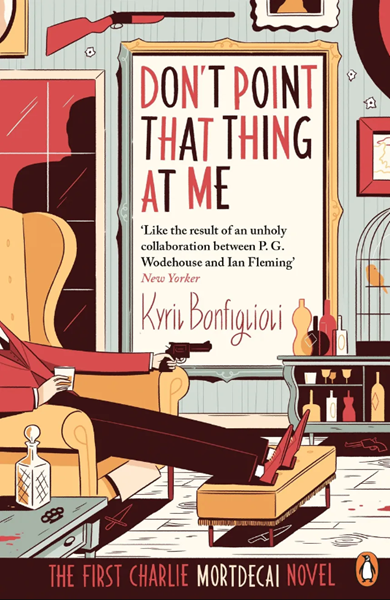

At The Conservative Woman, Alan Ashworth recommends a book by one of P.G. Wodehouse’s disciples, but only for those who are ready for Plum-like wit with “lashings of sex, violence, murder and drunkenness”:

If, like me, you have read every line of PG Wodehouse’s 90-odd books – at least half a dozen times each in the case of the Jeeves novels – your attention might be piqued, if piqued is the word I seek, by one of the Master’s disciples. His name is Kyril Bonfiglioli.

In a trilogy about an art dealer named Charlie Mortdecai based loosely on himself, Bonfiglioli, or Bon as his friends and enemies called him, combines a Woosterish turn of phrase with lashings of sex, violence, murder and drunkenness. Mortdecai is snobbish, greedy, lustful, unscrupulous, untrustworthy, gloriously politically incorrect and hilarious to boot.

The first book, Don’t Point That Thing At Me, was published in 1973, two years before Wodehouse died. In a short foreword, Bon writes: “This is not an autobiographical novel: it is about some other portly, dissolute, immoral and middle-aged art dealer.”

The action begins with Mortdecai in his Mayfair mansion burning a gilt picture frame in the fireplace. He, of course, has a sidekick whose name begins with J but Jock has little in common with Bertie Wooster’s loyal manservant. As Bon puts it, “Jock is a sort of anti-Jeeves; silent, resourceful, respectful even, when the mood takes him, but sort of drunk all the time, really, and fond of smashing people’s faces in. You can’t run a fine-arts business these days without a thug and Jock is one of the best in the trade … his idea of a civil smile is rolling back part of his upper lip from a long, yellow dogtooth. It frightens me.

“Having introduced Jock – his surname escapes me, I should think it would be his mother’s – I suppose I had better give a few facts about myself. I am in the prime of life, if that tells you anything, of barely average height, of sadly over-average weight and am possessed of the intriguing remains of rather flashy good looks. (Sometimes, in a subdued light and with my tummy tucked in, I could almost fancy me myself.) I like art and money and dirty jokes and drink. I am very successful. I discovered at my goodish second-rate public school that almost anyone can win a fight if he is prepared to put his thumb into the other fellow’s eye.”

Charlie is receiving a visit from a fat policeman named Martland who suspects him, correctly, of involvement in the theft of a Goya from Madrid five days earlier.

“Somewhere in the trash he reads, Martland has read that heavy men walk with surprising lightness and grace; as a result he trips about like a portly elf hoping to be picked up by a leprechaun. In he pranced, all silent and catlike and absurd, buttocks swaying noiselessly. ‘Don’t get up,’ he sneered, when he saw that I had no intention of doing so. ‘I’ll help myself, shall I?’

“Ignoring the more inviting bottles on the drinks tray, he unerringly snared the great Rodney decanter from underneath and poured himself a gross amount of what he thought would be my Taylor ’31. A score to me already, for I had filled it with Invalid Port of an unbelievable nastiness. He didn’t notice: score two to me. Of course he is only a policeman.”

Martland features heavily in the ensuing romp, which involves several murders, a journey across America in a Rolls-Royce, a nymphomaniac millionairess and a remote cave near Silverdale, Lancashire.

December 4, 2023

Jeeves and Wooster, in a nutshell …

Barcode

Published 11 Oct 2021A summary of the entire Jeeves & Wooster series in roughly 6 minutes.

P.G. Wodehouse’s Jeeves (played by Stephen Fry) and Bertie Wooster (Hugh Laurie) have been lauded as one of the greatest comic double acts of all time. Set in the late 1920s-1930s, Jeeves and Wooster (1990-1993) follows the hilarious misadventures of Bertram Wilberforce Wooster — a young, affable English gentleman of the idle rich — and Jeeves — Bertie’s omniscient and resourceful valet. Jeeves discreetly takes control of his “mentally negligible” employer’s life, while Bertie Wooster finds himself pushed and reeled into countless imbroglios, fiascoes, and romantic entanglements led by his hapless friends and imperious aunts. But each disaster is drawn to its own satisfactory conclusion through a concatenation of intriguing coincidences … or so they would seem. Until, that is, the silent force behind every “coincidence” is revealed to be none other than the brilliant and inimitable Jeeves.

(more…)

August 22, 2023

“… the theatrics employed by Hitler and Mussolini just seemed too weird and downright ridiculous to the British”

In Spiked, Ralph Schoellhammer discusses some of the difficulties the Green Gestapo, er, I mean the likes of Extinction Rebellion and their mini-mes like Just Stop Oil have been encountering with the British public:

Roderick Spode, 7th Earl of Sidcup, leader of the “Saviours of Britain”, also known as the Black Shorts.

Still from Jeeves and Wooster (1990).

I have long been convinced that one of the reasons why fascism never had a chance in Britain was due to the predispositions of her people. If nothing else, the theatrics employed by Hitler and Mussolini just seemed too weird and downright ridiculous to the British.

PG Wodehouse captured this perfectly in an exchange between a British wannabe fascist, Roderick Spode, and Bertie Wooster: “The trouble with you, Spode, is that just because you have succeeded in inducing a handful of half-wits to disfigure the London scene by going about in black shorts, you think you’re someone.”

I don’t intend to liken fascists to environmentalists, but Brits have at least expressed a similar, visceral distaste for the theatrics of eco-activist groups in recent years. Marching in black “footer bags”, pretending to be the voice of the people, is just as ridiculous as holding up traffic in an orange “Just Stop Oil” t-shirt.

The environmental movement becomes more absurd by the day. The Guardian‘s George Monbiot, for instance, has just called for the reintroduction of deadly wolves and lynxes to Great Britain, in order to manage a surging deer population. One can only hope that this call to action will have about as much success as his campaign against meat, milk and eggs, which Monbiot is convinced are an “indulgence” humanity can no longer afford.

Sadly, the same is not true in Germany, where the elites are all too keen to humour even the most extreme climate fanatics. German discount supermarket Penny recently decided to increase the prices of its meat and dairy products, to include the environmental costs incurred in their production, as part of a week-long experiment. The price of frankfurter sausages rose from €3.19 to €6.01. The price of mozzarella rose by 74 per cent, to €1.55. And the price of fruit yoghurt rose by 31 per cent, from €1.19 to €1.56.

While the usual suspects in the establishment are clearly excited by this idea that in the future even shopping at a discount shop might become the preserve of the rich, average Germans are less pleased. Germany’s public broadcaster, WDR, asked Penny customers what they thought about the price-hike experiment. Due to a lack of enthusiasm from shoppers, WDR decided to have one of its employees cosplay as a happy shopper. That taxpayer-funded broadcasters now have to resort to outright fraud in order to drum up support for idiotic climate action tells you everything you need to know.

May 1, 2023

Balm for a golfer’s soul

Alan Ashworth wants to persuade you to read the works of P.G. Wodehouse. In this installment, he appeals to the golfers in the audience:

When Pelham Grenville Wodehouse was at Dulwich College between 1894 and 1900, he was blissfully happy with school life and developed an enduring love of cricket and rugger – he went off boxing because the other blighters kept hitting him. The two sports were central to his early novels and he followed Dulwich’s results throughout his long life.

Yet when Plum began to enjoy success in the US he realised that to mine the rich comic seam of sporting obsession he had to come up with a new ball game.

During a lengthy spell in America, where he had become a big noise in musical theatre, he began to play golf at the Sound View club in Long Island with comic actors including Ed Wynn and Ernest Truex. “The golf course was awfully nice,” he recalled many years later. “However, I wasn’t any good at golf. I suppose I ought to have taken lessons instead of playing. I didn’t mind losing, because it was such good exercise walking around the holes. If only I’d taken up golf immediately after I left school instead of playing cricket.”

He never did get very good at the game. Over the years he won a single trophy, a striped umbrella, at a hotel tournament “where, hitting them squarely on the meat for once, I went through a field of some of the fattest retired businessmen in America like a devouring flame”.

However, golf was to provide the material for some of Wodehouse’s finest short stories, written mainly in the 1920s, which helped to make him a very rich man.

As one of his biographers, Richard Usborne, observed in his marvellous Wodehouse at Work to the End, “in the 1920s and 30s there were many illustrated magazines on both sides of the Atlantic paying high for good humorous short stories, five- to eight-thousand-word episodes, complete with sunny plot, a beginning, middle and end, and the young couple happily paired off in the fade-out. Wodehouse wrote for this profitable market. He became one of the golden boys of the magazines and, not necessarily the same thing, a master of his craft.”

April 18, 2023

“Here it is then. This is The Hill.”

Simon Evans rightfully decides that fighting the bowdlerization of P.G. Wodehouse is the hill to die on:

PG Wodehouse has become the latest author to fall victim to the “sensitivity readers”. Passages have been purged and words have been altered for the new editions of his Jeeves and Wooster novels, including Thank You, Jeeves and Right Ho, Jeeves. According to Penguin, the publishers, some of the racial language and themes of these 1930s novels are “outdated” and “unacceptable”. This includes the use of the n-word.

When I saw the news, my tweet sort of fell out of me before I’d consciously drafted it: “Here it is then. This is The Hill.”

There is an interesting contrast here. We live in a time when every much-loved and out-of-copyright literary artefact that is brought to the screens is being stiffened, like an old Christmas pudding recipe that clearly needs more brandy, with swearing and novel scenes of sexual deviation never imagined in the original. Just think of the BBC’s recent modernising and coarsening of Charles Dickens, Agatha Christie et al, which have rendered them all but unwatchable for millions. So it is more than a little odd that Wodehouse, the mildest, most weightless comedy of the last century, should suddenly seem deserving of the nit comb.Yes, it is true that Wodehouse uses the n-word. And no other word is now, or arguably ever has been, quite so radioactive, so sui generis in its capacity for offence. It is not that I want to defend this word. Rather, the hill on which I will die is the pristine perfection of Wodehouse’s prose, and its right to remain so. He is – and by an extraordinary degree of consensus, in a field that is almost maddeningly subjective – the Bach of comic literature. And I’m sorry, but you just don’t tinker with Bach.

Though a fan, Christopher Hitchens, in a review of a Wodehouse biography, wrote of the tiresome habit of certain people in referring to Wodehouse as “The Master”, so I will try to avoid that unctuous, fulsome tone. But one of the very few writers of my lifetime who approached him for touch (though sadly not in output) was Douglas Adams, who often referred to Wodehouse as just that: “He’s up in the stratosphere of what the human mind can do, above tragedy and strenuous thought, where you will find Bach, Mozart, Einstein, Feynman and Louis Armstrong, in the realms of pure, creative playfulness.”

The point is not that the presence of the odd unfortunate archaic usage, which might indeed jolt the casual reader into a brief awareness that they are reading something older than their grandfather, is necessarily a good thing. It is simply, who the hell do the sensitivity readers think they are, to decide what stays and what goes?

April 1, 2023

QotD: P.G. Wodehouse and Sir Oswald Mosley

The majority of his tales are set in country houses, replete with conservatories, libraries, gun rooms, stables and butler’s pantries. Letters arrive by several posts a day, telegrams by the hour. Trains run on time from village stations. Other than the pinching of policemens’ helmets, there is order and serenity. Necklaces are filched, silverware is purloined, butlers snaffle port, chums are impersonated, romances develop in rose gardens, but nothing lurks to fundamentally reorder society.

There was one exception. The object of Wodehousian scorn was the moustachioed leader of Britain’s black-shirted Fascists, Sir Oswald Mosley, 6th Baronet. A fencing champion at school, dashing war record in the Flying Corps, and a Member of Parliament, he was the recipient of an inherited title, with a family tree that stretched back to the 12th century, a country house and a Mayfair residence. In Wodehouseland, Mosley is transformed into the equally aristocratic Roderick Spode, 7th Earl of Sidcup.

Plum was intolerant of even the vaguest of threats to the established order of things. He voiced his dislike of Spode through Bertie Wooster, likening the fascist leader to one of “those pictures in the papers of dictators, with tilted chins and blazing eyes, inflaming the populace with fiery words on the occasion of the opening of a new skittle alley”. Plum focussed his gaze on the Spode/Mosley moustache, which was “like the faint discoloured smear left by a squashed black beetle on the side of a kitchen sink”, describing its owner as “one who caught the eye and arrested it”.

The proto-dictator appeared, thought Wodehouse, “as if Nature had intended to make a gorilla but had changed its mind at the last moment”. Every reader would have known it was Mosley in the crosshairs, because Spode was the leader of a fascist group called the “Saviours of Britain, also known as the Black Shorts”. The transition of attire is because, as another of Wodehouse’s masterful creations, Gussie Fink-Nottle, observed, “by the time Spode formed his Association, there were no black shirts left in the shops”.

A different Wodehouse character warned, “Never put anything on paper … and never trust a man with a small black moustache.” Indeed, anyone “whose moustache rose and fell like seaweed on an ebb-tide” was best avoided. Plum could have been referring to Mosley or Hitler. The former, as leader of Britain’s real-life black shirts, was an unashamed admirer of the latter, and he interned in Holloway prison during the war. Afterwards, as an advocate of what we today would call Holocaust denial, he moved to Paris where he died in 1980. His political journey was interesting. Mosley started as a Conservative, drifted leftwards into the Labour Party, then further left into his own independent party, which evolved into the right-wing British Union of Fascists.

Modelled on the Italian and German fascist movements, Mosley and his supporters came to believe that “Jewish interests commanded commerce, the Press, the cinema, dominated the City of London, and killed British industry with their sweatshops”. Fascism lurking in the upper classes troubled Plum Wodehouse so greatly that Spode and his Black Shorts appeared in five of his works between 1938–74.

Peter Caddick-Adams, “Coups and coronets”, The Critic, 2022-12-13.

March 20, 2023

QotD: The world of “Plum”

“It was a confusion of ideas between him and one of the lions he was hunting in Kenya, that caused A. B. Spottsworth to make the obituary column. He thought the lion was dead, and the lion thought it wasn’t.” The author of these lines, P.G. Wodehouse, understood a thing or two about humour. Written seventy years ago, his wit sparkles on, undimmed.

The maestro also knew a thing or two about politics. This is strange, for few of his nearly one hundred novels, short stories or plays betray more than a nodding acquaintanceship with the great upheavals of the 20th century. Enquiring deeper, the connoisseur will find that his eternal creation, Jeeves — the discreet, silent, valet-cum-butler extraordinaire — was named in honour of a popular English cricketer who died on the Somme in 1916. The subject himself, in a post-1945 volume, admitted to his employer Bertie Wooster that he had “dabbled somewhat in the Commandos” during the Second World Conflagration.

War and turmoil are there, lurking in the background, if successfully banished from much of his writing. Sadly, Pelham Grenville (forenames he hated, so adopted the moniker “Plum” instead) was naïve. Loafing professionally in France when the Wehrmacht knocked on his door for tea and crumpets in 1940, he and his wife were interned as enemy aliens. In 1941, Plum agreed to record five broadcasts to the USA, then neutral. Entitled How to be an Internee without previous Training, they comprised playful anecdotes about his experiences as a prisoner of the folk in field grey. I’ve read them. They are rib-tickling and harmless, and his American readers lapped them up. Alas, his British fan club took a different view.

The devotees of Bertie Wooster, Reginald Jeeves, the Earl of Emsworth, Sir Roderick Glossop and Co. were at first stunned, then vexed and finally branded the poor author a traitor. Although a post-war MI5 investigation exonerated him, a hurt Wodehouse thereafter lived in exile on Long Island. Fortunately for us, the flow of humour continued unabated, but Plum’s hard-earned Knighthood for conjuring up the essence of Bottled Englishness was long delayed until the New Year’s Honours of 1975. He died soon after, on St Valentine’s Day, aged ninety-three.

This lapse of judgement was all the more extraordinary given his ability to spot a scoundrel at one hundred paces. Threats to the serene, ordered nature of English society in which he resided — indeed helped to create — were few. In Wodehouse’s Garden of Eden, there is a definite hierarchy of earls and aunts, bishops, baronets and young blades, stationmasters and policemen.

The majority of his tales are set in country houses, replete with conservatories, libraries, gun rooms, stables and butler’s pantries. Letters arrive by several posts a day, telegrams by the hour. Trains run on time from village stations. Other than the pinching of policemens’ helmets, there is order and serenity. Necklaces are filched, silverware is purloined, butlers snaffle port, chums are impersonated, romances develop in rose gardens, but nothing lurks to fundamentally reorder society.

Peter Caddick-Adams, “Coups and coronets”, The Critic, 2022-12-13.

March 11, 2023

“… when people are sticking warning labels on P.G. Wodehouse, something is seriously wrong”

In The Conservative Woman, Alan Ashworth stands aghast at the very notion of putting a content warning on an adaptation of a P.G. Wodehouse short story:

Dominic Sandbrook in the Mail on Sunday draws attention to BBC Radio 4 Extra and its latest repeat of an adaptation of P.G. Wodehouse’s Psmith in the City. It is preceded by an announcement that listeners should steel themselves for “some dated attitudes and language”.

You don’t say. The story was written well over a century ago, appearing first as a serial in The Captain magazine in 1908 and 1909 before being published as a book by A & C Black in 1910.

In it Psmith (the P is silent) and his old school friend Mike Jackson are reunited when they find themselves working for the New Asiatic Bank, a thinly disguised portrait of the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank (now HSBC) where Wodehouse himself endured a torrid spell before his writing career took off.

The two chums have several run-ins with management and Mike is eventually fired before Psmith solves all his problems and has him reinstated. Of course, as always in Wodehouse’s world, there is no sex, no angst, nothing to frighten the horses.

So why the BBC announcement? Sandbrook writes: “At first I wondered if this must be some mistake. Perhaps the warning had been transposed from some more dangerous programme, such as a stand-up show by Bernard Manning?

“But the warning was meant for Psmith. So what were these toxic and potentially traumatising attitudes? For the life of me, I still don’t really know.

“At one point, Psmith talks of going ‘out East’, where you have ‘a dozen native clerks under you, all looking up to you as the Last Word in magnificence’. But was that it? Did that merit a warning?

“As it happens, this radio adaptation was made in 2008. Did the actors realise they were participating in something steeped in sick imperialistic assumptions? I doubt it.

“Venturing into the cesspit of social media, I often find Left-wing pundits insisting there is no such thing as cancel culture and that the whole thing is an evil Tory myth.

“But when people are sticking warning labels on P G Wodehouse, something is seriously wrong. Indeed, you could hardly find a more ludicrous target, because he was one of most tolerant, generous-spirited writers imaginable. So generous-spirited that he’d probably have laughed this off. ‘I never was interested in politics,’ Wodehouse once remarked. ‘I’m quite unable to work up any kind of belligerent feeling.’

“Being cut from a meaner cloth, however, I do feel worked up about it. When I think of these finger-wagging commissars sitting in judgment on a writer who has given so much pleasure to so many readers, I feel like Bertie Wooster’s Aunt Agatha, gearing herself up before a titanic tirade.

“Do we really need a warning that P G Wodehouse is ‘dated’? What next? A lecture before Hamlet, to warn us that poisoning your wife or killing your uncle is now considered poor form? A warning before Roald Dahl or Ian Fleming?

“But, of course, Dahl and Fleming don’t need warnings now, for they have been posthumously updated.”

February 1, 2022

QotD: Intoxication

Intoxicated? The word did not express it by a mile. He was oiled, boiled, fried, plastered, whiffled, sozzled, and blotto.

P.G. Wodehouse, Meet Mr. Mulliner, 1927.

January 18, 2022

QotD: The role of fate in man’s affairs

I’m not absolutely certain of the facts, but I rather fancy it’s Shakespeare who says that it’s always just when a fellow is feeling particularly braced with things in general that Fate sneaks up behind him with the bit of lead piping.

P.G. Wodehouse, “Jeeves and the Unbidden Guest”, My Man Jeeves, 1919.

May 20, 2021

QotD: Jeeves

Jeeves — my man, you know — is really a most extraordinary chap. So capable. Honestly, I shouldn’t know what to do without him. On broader lines he’s like those chappies who sit peering sadly over the marble battlements at the Pennsylvania Station in the place marked “Inquiries.” You know the Johnnies I mean. You go up to them and say: “When’s the next train for Melonsquashville, Tennessee?” and they reply, without stopping to think, “Two-forty-three, track ten, change at San Francisco.” And they’re right every time. Well, Jeeves gives you just the same impression of omniscience.

As an instance of what I mean, I remember meeting Monty Byng in Bond Street one morning, looking the last word in a grey check suit, and I felt I should never be happy till I had one like it. I dug the address of the tailors out of him, and had them working on the thing inside the hour.

“Jeeves,” I said that evening. “I’m getting a check suit like that one of Mr. Byng’s.”

“Injudicious, sir,” he said firmly. “It will not become you.”

“What absolute rot! It’s the soundest thing I’ve struck for years.”

“Unsuitable for you, sir.”

Well, the long and the short of it was that the confounded thing came home, and I put it on, and when I caught sight of myself in the glass I nearly swooned. Jeeves was perfectly right. I looked a cross between a music-hall comedian and a cheap bookie. Yet Monty had looked fine in absolutely the same stuff. These things are just Life’s mysteries, and that’s all there is to it.

But it isn’t only that Jeeves’s judgment about clothes is infallible, though, of course, that’s really the main thing. The man knows everything. There was the matter of that tip on the “Lincolnshire.” I forget now how I got it, but it had the aspect of being the real, red-hot tabasco.

“Jeeves,” I said, for I’m fond of the man, and like to do him a good turn when I can, “if you want to make a bit of money have something on Wonderchild for the ‘Lincolnshire.'”

He shook his head.

“I’d rather not, sir.”

“But it’s the straight goods. I’m going to put my shirt on him.”

“I do not recommend it, sir. The animal is not intended to win. Second place is what the stable is after.”

Perfect piffle, I thought, of course. How the deuce could Jeeves know anything about it? Still, you know what happened. Wonderchild led till he was breathing on the wire, and then Banana Fritter came along and nosed him out. I went straight home and rang for Jeeves.

“After this,” I said, “not another step for me without your advice. From now on consider yourself the brains of the establishment.”

“Very good, sir. I shall endeavour to give satisfaction.”

And he has, by Jove! I’m a bit short on brain myself; the old bean would appear to have been constructed more for ornament than for use, don’t you know; but give me five minutes to talk the thing over with Jeeves, and I’m game to advise any one about anything.

P.G. Wodehouse, “Leave it to Jeeves”, My Man Jeeves, 1919.

March 21, 2021

QotD: Expressions of love

Love is a delicate plant that needs constant tending and nurturing, and this cannot be done by snorting at the adored object like a gas explosion and calling her friends lice.

P.G. Wodehouse, Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit.