Alex Harrowell explains the deep suspicions among Germans which long predate the NSA surveillance revelations:

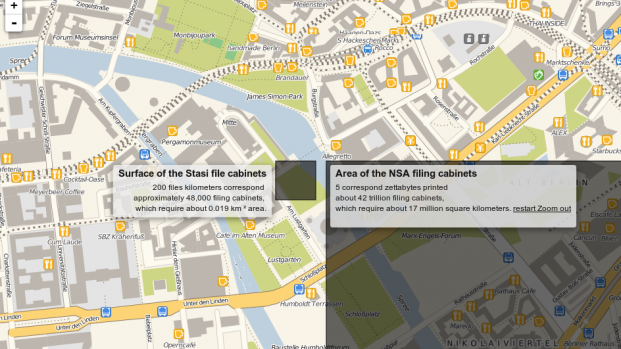

Obviously, privacy and data protection are especially sensitive in Germany. After the Stasi, the centrality of big databases to the West German state’s response to the left-wing terrorists of the 1970s, and the extensive Nazi use of telephone intercepts during the seizure of power, it couldn’t really be otherwise. Privacy and digital activism is older and better established in Germany than anywhere else — in the US, for example, I consider the founding text of the movement to be the FBI vs. Steve Jackson Games case from 1990 or thereabouts, while the key text in Germany is the court judgment on the national census from ten years earlier. But the UK has a (strong) data protection act and no-one seems anywhere near as exercised, although they probably should be.

So here’s an important German word, which we could well import into English: Deutungshoheit. This translates literally as “interpretative superiority” and is analogous to “air superiority”. Deutungshoheit is what politicians and their spin doctors attempt to win by putting forward their interpretations and framings of the semirandom events that constitute the “news”. In this case, the key event was Snowden’s disclosure of the BOUNDLESS INFORMANT slides, which show that the NSA’s Internet surveillance operations collect large amounts of information from sources in Germany.

The slides don’t say anything about how, whether this was information on German customers handed over by US cloud companies under PRISM orders, tapped from cables elsewhere, somehow collected inside Germany, or perhaps shared with the NSA by German intelligence. This last option is by far the most controversial and the most illegal in Germany. The battle for Deutungshoheit, therefore, consisted in denying any German involvement and projecting the German government, like the people in question, as passive victims of US intrusion.

On the other hand, Snowden’s support-network in the Berlin digital activist world, centred around Jacob “ioerror” Applebaum, strove to imply that in fact German agencies had been active participants, and Snowden’s own choice of further disclosures seems to have been guided by an intent to influence German politicians. Der Spiegel, rather than the Guardian, has been getting documents first and their content is mostly about Germany.

In this second phase, the German political elite has shifted its feet; rather than trying to deny any involvement whatsoever, they have instead tried to interpret the possibility of something really outrageous as being necessary for your security, and part of fundamental alliance commitments which cannot be questioned within the limits of respectable discourse. The ur-text here is Die Zeit‘s interview with Angela Merkel, in which Merkel argues that she knew nothing, further that there was a balance to strike between freedom and security, that although some kinds of spying were unacceptable, the alliance came first. The effectiveness of this, at least in the context of the interview, can be measured by astonishingly uncritical questions like the one in which she was asked “what additional efforts were necessary from the Germans to maintain their competitiveness”.

H/T to Tyler Cowen for the link.