What about pictures? We call this representational evidence. Representational evidence can be quite good at telling you what something looked like (but beware of artistic conventions!), but is of course little help for the names-and-dates kind of historical work. The larger problem though is that representational evidence especially becomes difficult to interpret without literary or archaeological evidence backing it up. The problem of correlating an image to a specific person or object can be very hard (by way of example, the endless debates about what is meant by kotthybos in the Amphipolis military regulations). Representational evidence gets a lot more useful if you can say, “Ah, X depicts Z events from B-literary-source” but obviously to do that you need to have B-Literary-Source and B is going to do most of the heavy lifting. To see just how hard it can be to use representational evidence without a robust surviving literary tradition, one merely needs to look at work on pre-historic Gaul (it’s hard!).

Which brings us at last to the big dog, archaeological evidence (although all of the aforementioned also show up in the archaeological record). Archaeology is wonderful, easily the biggest contributor to the improvement in our knowledge of the ancient world over the last century; my own research relies heavily on archaeological evidence. And the best part of it is we are getting more and better archaeological evidence all the time. Some archaeological finds are truly spectacular, like the discovery of the remains of the wrecks from the Battle of the Aegates Islands (241), the decisive engagement that ended Rome’s first war with Carthage (underwater archaeology in general in a young part of archaeology, which is itself a young field so we may well expect more marvels to come).

But (you knew there would be a but), archaeological evidence is really only able to answer certain specific questions and most research topics are simply not archaeologically visible. If your research question is related to what objects were at a specific place at a given time (objects here being broad; “pots” or “houses” or “farms” or even “people” if you are OK with those people being dead), good news, archaeology can help you (probably). But if your research question does not touch on that, you are mostly out of luck. If your object of study doesn’t leave any archaeological evidence … then it doesn’t leave any evidence. Most plagues, wars, famines, rulers, laws simply do not have archaeologically visible impacts, while social values, opinions, beliefs don’t leave archaeological evidence in any case.

Take, for instance, our evidence for the Cult of Mithras in the Roman Empire. This religion leaves us archaeological evidence in the form of identifiable ritual sanctuaries (“mithraeums“). Archaeology can tell us a lot about the normal size and structure of these places, but it can’t tell us much about what people there believed, or what rituals they did, or who they were, with only a handful of exceptions, which is why so much of what we think we might know about Mithraism is still very speculative.

Moreover, archaeology only works for objects that leave archaeological remains! Different materials preserve at different rates. Ceramic and stone? Great! Metals? Less great; these tend to get melted down when they don’t rust. Wood or textiles? Worse, almost never survives. This is why we have so much data on loom weights (stone, ceramic) but less on looms (wood, textile), and so much data on spindle whorls (stone, ceramic) but less on spindle-sticks or distaffs (wood). Compounding this are preservation accidents, in that things that survive tend to be things thrown away or buried with bodies and those practices will impact your archaeological record.

But the best part about archaeology is that it has network effects, which is to say that the more archaeology we do, the more useful each find becomes. New discoveries help to date and understand old discoveries and with lots of archaeological evidence, you can do really neat things like charting trade networks or changing land-use patterns. The problem is that you really do need a lot to generate a representative sample so you know you aren’t wrongly extrapolating from exceptions, and for right now, only the best excavated regions (Italy, to a lesser extent Greece and Egypt) are at the point where we can talk about, for instance, changing patterns of land use and population with any detail. And even then, uncertainties are huge.

Finally, archaeology, like everything else, works best with literary evidence. Take, for example, pre-Roman Gaul. The Gauls, due to their deposition practices are very archaeologically visible. Rich burial assemblages, large ritual deposits and archaeologically visible hill-fort settlements mean that the archaeological record for pre-Roman Gaul is very robust (in some cases more robust that the equivalent Roman context; we can be far more confident about the shape and construction of Gallic weapons than contemporary Roman ones, for instance). But effectively no literary sources for Gaul until contact with the Romans and Greeks. Consequently, almost everything about their values, culture, social organization in the pre-Roman period is speculative, with enormous numbers of questions and few answers.

If you want to ask me, “When did the Gauls shift to using longer swords” I can tell you with remarkable precision, in some cases, region by region (but generally c. 250 BC, with the trend intensifying in the late second century). But if you want to ask, “what was it like to rule a Gallic polity in c. 250 BC?” The best we can do is reason from what we see Caesar describing in c. 50 BC and hope that was typical two hundred years earlier.

Bret Devereaux, “Fireside Friday: March 26, 2021 (On the Nature of Ancient Evidence”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-03-26.

June 30, 2024

QotD: The use of pictorial and archaeological evidence in studying the ancient world

February 8, 2024

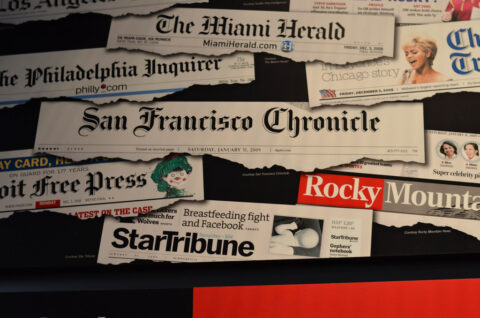

North American newspaper economics

Tim Worstall discusses some of the issues ailing Canadian and American newspapers which are not easily solvable (government subsidies, as attempted in Canada, just turn the recipients into an underpaid PR branch of the governing party … not a good look in a democratic nation):

So, as a little corrective, a quick jaunt through what actually ails American journalism. The concentration is upon the big newspapers because that’s where the problem is worst. The conclusion is that it’s gonna get a lot, lot, lot, worse too. Because the industry is facing a base economic problem that it’s not willing to actually face up to. Or, at least, all the journalists writing about it aren’t — there’s the occasional sign that some of the business side of the equation grasp it.

[…]

Before Y2K American newspapers were segmented along geographic lines. The size of the country, the lack of a long distance passenger railroad network, meant that this was just so. If you’re printing a daily paper then you’ve got to deliver it daily. On the day it’s meant to refer to as well. If Chicago is 1,100 miles (no, I’ve not looked it up but that’s within an order of magnitude of being right, which is better than many newspapers manage with numbers) from New Orleans then the same newspaper is going to find it difficult to print and deliver to both markets. Add in the fact that trains take a week to traverse that distance, passenger trains – anyone who has ever travelled Amtrak will say it feels that long at least — included.

You could not and therefore did not have national newspaper (USA Today, with satellite printing plants, was an attempt to deal with this and slightly earlier than our cut off date but doesn’t change the basic story) distributions. What you had was a series of local and regional monopolies. Each one centred on a large population centre and serving the area around it that could be reasonably reached by truck overnight. Chicago and Cincinnati, not 1,100 miles away from each other, did have entirely different newspapers.

By contrast, and just as an example, the British newspaper market was national from pre-WWI. We simply did have overnight at worst passenger rail that covered the country. Partly it’s a much, much, smaller place, partly the passenger rail system was just different. So, printing overnight (and some maintained separate Scottish editions and plants) meant that those papers that came off the press in London at 8pm were on sale in Glasgow at 8 am, those that came off the press in London at 4 am were on sale in London at 8am. That’s not exact but it’s a good enough pencil sketch.

Cincinnati newspaper(s) served Cincinnati. Chicago, Chicago and New Orleans the area of New Orleans. There simply wasn’t a “national press” in the US in that British sense.

OK. But this also meant that American newspapers were much more like a monopoly in their local area than anything else. Network effects still exist even before computer networks after all. The most important of which was the classifieds.

As with Facebook, we’re all on Facebook because everyone else is on Facebook. So, if we’re to join a social network we’re going to be on Facebook where everyone else is — except those three hipsters who are where it isn’t cool yet. This applies to classifieds sections. Folk advertise in the one with the most readers, the widest market. Readers buy the one with the most ads in it, the widest market. You advertise the bronzed baby shoes, unused, where there are the most people looking for bronzed baby shoes, unused.

So, the dominant paper will suck up the classifieds in any particular market. Classifieds, fairly obviously back in the days of prams, cheap used cars, waiters’ jobs and so on being geographically based.

No, this is important. A useful pencil sketch of American newspaper revenues pre-Y2K was that subscriptions produced some one third of revenues. They also, around and about, covered print costs and distribution. They were, roughly you understand, about a face wash in fact.

Display ads produced another one third and classifieds the final one third. Classifieds were also wildly profitable — no expensive journalists to pay, no bureaux, just a few women waiting to get married on the end of the phone line.

May 4, 2023

Why British train enthusiasts hate this man – Dr. Beeching’s Railway Axe

Train of Thought

Published 27 Jan 2023In today’s video, we take a look at one Doctor Richard Beeching, the man who ripped up a third of Britain’s railways with nothing but a pen and paper.

March 29, 2022

Abandoned: How The Beeching Report Decimated Britain’s Railways | Timeline

Timeline – World History Documentaries

Published 15 May 2019Travel journalist Simon Calder takes a journey from across the south of England — by bike, rail and car. In this documentary film, Simon explores the legacy of the Beeching railway cuts. He examines the arguments for reopening some of the branch lines axed in the 1960s.

It’s like Netflix for history … Sign up to History Hit, the world’s best history documentary service, at a huge discount using the code ‘

TIMELINE‘ —ᐳ http://bit.ly/3a7ambuYou can find more from us on:

https://www.instagram.com/timelineWH

This channel is part of the History Hit Network. Any queries, please contact owned-enquiries@littledotstudios.com

October 14, 2021

March 3, 2019

QotD: Four ways to corporate monopoly

1. Proprietary technology. This one is straightforward. If you invent the best technology, and then you patent it, nobody else can compete with you. Thiel provocatively says that your technology must be 10x better than anyone else’s to have a chance of working. If you’re only twice as good, you’re still competing. You may have a slight competitive advantage, but you’re still competing and your life will be nasty and brutish and so on just like every other company’s. Nobody has any memory of whether Lycos’ search engine was a little better than AltaVista’s or vice versa; everybody remembers that Google’s search engine was orders of magnitude above either. Lycos and AltaVista competed; Google took over the space and became a monopoly.

2. Network effects. Immortalized by Facebook. It doesn’t matter if someone invents a social network with more features than Facebook. Facebook will be better than their just by having all your friends on it. Network effects are hard because no business will have them when it first starts. Thiel answers that businesses should aim to be monopolies from the very beginning – they should start by monopolizing a tiny market, then moving up. Facebook started by monopolizing the pool of Harvard students. Then it scaled up to the pool of all college students. Now it’s scaled up to the whole world, and everyone suspects Zuckerberg has somebody working on ansible technology so he can monopolize the Virgo Supercluster. Similarly, Amazon started out as a bookstore, gained a near-monopoly on books, and used all of the money and infrastructure and distribution it won from that effort to feed its effort to monopolize everything else. Thiel describes how his own company PayPal identified eBay power sellers as its first market, became indispensible in that tiny pool, and spread from there.

3. Economies of scale. Also pretty straightforward, and especially obvious for software companies. Since the marginal cost of a unit of software is near-zero, your cost per unit is the cost of building the software divided by the number of customers. If you have twice as many customers as your nearest competitor, you can charge half as much money (or make twice as much profit), and so keep gathering more customers in a virtuous cycle.

4. Branding. Apple is famous enough that it can charge more for its phones than Amalgamated Cell Phones Inc, even for comparable products. Partly this is because non-experts don’t know how to compare cell phones, and might not trust Consumer Reports style evaluations; Apple’s reputation is an unfakeable sign that their products are pretty good. And partly it’s just people paying extra for the right to say “I have an iPhone, so I’m cooler than you”. Another company that wants Apple’s reputation would need years of successful advertising and immense good luck, so Apple’s brand separates it from the competition and from the economic state of nature.

Scott Alexander, “Book Review: Zero to One”, Slate Star Codex, 2019-01-31.

March 29, 2018

March 7, 2018

Language and the network effect

Tim Worstall in the Dhaka Tribune:

A recent article on the Dhaka Tribune reported that Bangladesh as a country, as an idea, is rather closely linked with the idea of Bangla as a language. Languages having much to do with something economists find fascinating, network effects.

Indeed, we can explain what happens with languages, with Facebook and with currencies all using these same effects. We end up, as we so often do in economics, with the answer: “It depends.”

Let us leave aside those cultural and political issues, the difference between an official language and a mother tongue and mother language. Instead, consider those as networks. Why is it that Facebook has conquered every other form of social media? For the same reason that one fax machine is an expensive paperweight, two allows information to flow, and millions means those millions can communicate with each other.

So it is with anything subject to strong network effects.

We all go on Facebook because everyone else is there, that everyone else is there means more people join it. The standards fax machines use to talk to each other are just the one set of standards precisely so that they can all communicate.

We might think that the same should be true of language. We could all communicate with each other much more easily if there was just the one language used to do so. Often there is a lingua franca which allows this — say, Latin in the past and English now.

But that’s not really how we humans work. Even Bangla is not the same in each and every area of the country, just as English isn’t even in England. There are local dialects which are not mutually intelligible; we use a simplified or standardized version to speak with people from other areas — this is where the “BBC accent” comes from.

The same is true of German for example, people from different areas cannot understand each other using their local variations so they use a standardized German which no one really speaks at home.

One story — a true one — has it that when John F Kennedy said “Ich bin ein Berliner” in a speech at the Berlin Wall he actually said in the local dialect that he was a jam doughnut. Common German and local are not the same thing at all.

The reason for this is that the language varies from household to household. Every family does have its own little private inside jokes; anyone who has ever met the in-laws knows this.

So too do neighbourhoods, villages and so on. A national language is like a patch-work quilt of these local variations.

To put this into economic terms of our networks, yes, we have that efficiency argument that we should all be using the same inter-changeable language, but that’s just not what we do. There’s a strong force, just us being people, breaking that language up into local variants, as happened with Latin and then Portuguese, Spanish, French, and Italian over the centuries.

October 12, 2017

Britain’s Old Boy Network – from “the Establishment” to “the Embarrassment”

In the media rounds supporting his new book, The Square and the Tower: Networks, Hierarchies and the Struggle for Global Power, Niall Ferguson discusses the decline and fall of the oldest power network in Britain:

It used to be that the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland was the United Cronydom of Great Poshhouse and Northern Grousemoor. The only network that mattered was the Old Boy Network. The OBN was formed by men who were the old boys of a tiny elite of boarding schools known as “public schools” because they were closed to the public. Most boys at those schools were scions of the aristocracy or the landed gentry: future barons and baronets.

Even if thick to the point of educational sub-normality, these young gentlemen would attend either Oxford or Cambridge. They would then be given one of the following jobs:

1. Estate manager and courtier (eldest son).

2. Foreign Office or Treasury mandarin (brightest son).

3. Cabinet minister (most extrovert son).

4. Governor of [insert Caribbean island] (youngest son).

5. BBC director-general (Left-wing son).

This is of course a caricature. In reality, there were all kinds of sub-networks — clusters — within the elite network that ran Britain. Sometimes, a brilliant group of talented young men would come together to achieve great things. There was the “Kindergarten” formed by Alfred Milner, which tried (and failed) to transform South Africa into a second Canada or Australia. There were the Apostles — the Cambridge Conversazione, the most exclusive intellectual club of all time — to which the economist John Maynard Keynes belonged.

However, with increasing frequency after 1945, the OBN’s achievements were less than brilliant. Suez. Wilson. Heath. Double-digit inflation. The three-day week. From being the winners of glittering prizes, the OBN degenerated in the eyes of a previously deferential public into the upper-class twits of the year.

In the Sixties the journalists Henry Fairlie and Anthony Sampson popularised the disdainful name that the historian A.J.P. Taylor had given the British elite: “The Establishment”. By the Seventies the Establishment were more like The Embarrassment — objects of sitcom ridicule. By the Eighties they had been almost entirely driven from the corridors of power. Nothing better illustrated this than the Thatcher governments: not only was the prime minister a woman from provincial Lincolnshire (albeit one with an Oxford degree); there were enough ministers in her Cabinet with Jewish backgrounds to inspire off-colour jokes about “Old Estonians”.

October 6, 2017

Regulation and the unregulated sharing economy

This particular article talks about the situation in Australia, although it’s quite similar here in Canada:

Living in Australia sometimes feels like living in a bureaucrats’ version of a spaghetti western. The heroes are the brave and all-knowing public servants, while the villains are the naughty people who are too foolish to realise that government knows best.

Politicians and bureaucrats alike want to regulate first, ask questions later. It seems barely a week passes without someone trumpeting the expansion of the nanny state. And with each new crackdown, ban or tax, our freedom gets that little bit smaller.

Whereas once the government would at least go through the motions of citing things like market failure, all it takes now is for a politician to want to look tough or be seen ‘doing something’. So it is with the proposed regulation of short-term accommodation platforms like Airbnb and Stayz.

Sharing our home with someone is as old as time. Who has not stayed with a family member or friend, or the friend of a friend? The difference these days is that it is much easier. Technology allows us to stay in someone’s home nearly anywhere in the world.

The immense popularity of these platforms is simply staggering. Globally, Airbnb has just passed four million listings, more than the rooms of the top five hotel brands worldwide. Australia is particularly fertile ground for the company, with almost one in five adults having an account. The company claims Airbnb is the “most penetrated market in the world”.

For government, the platforms are confronting. With no red tape or government involvement, travellers are protected, bad apples ejected and quality maintained via hosts and guests providing reviews of each other using sophisticated technology and a trusted online marketplace. Airbnb says that, on average, a host could have a new reservation every day for over 27 years before experiencing a single bad incident. A track record like that would be the envy of any pub, hotel, motel or caravan park in the country.

The so-called sharing economy challenges the idea that people need red tape, regulations or government to keep them safe from harm. But that does not stop some from trying. Currently, the NSW Government is toying with a grab bag of Big Brother and nanny-state policies ranging from new taxes and caps, to licences, planning approval and complete bans.

No modern government has ever seen a healthy, flourishing market without feeling the need to insert itself into the process, usually justified by the need to “protect” consumers.

July 13, 2017

QotD: What are “network effects”?

Few buzzwords are hotter in tech circles than “network effects.” This was so 15 years ago, when I was an MBA candidate grinding through job interviews; it is so today. Probably, when the heat death of the universe is imminent, and our nine-tailed descendants are trying to figure out what to do, some bright Johnny will suggest we can keep things going if we can just add another 2 billion stars to our user base.

Don’t get me wrong: Network effects are important, and I frequently talk about them in relation to everything from media companies to neighborhoods to choices about motherhood. But when I hear the term, the hairs rise on the back of my neck, because it’s often used imprecisely. People say “network effects” when they are really talking about switching costs, or regulatory coordination, or spillover effects, or any number of other things that are at best tangentially related to what the network effect model was built to describe.

Worse, far too many people seem to use the term the way college sophomores deploy the names of philosophers they have just read, in the mistaken belief that a piece of jargon can magically banish disagreement. Your firm doesn’t seem to have a viable revenue model? You’re just saying that because you don’t understand network effects! Someone seems insufficiently worried about the market power of some technology behemoth? It must be because that benighted fool has never heard about network effects!

Network effects are a useful concept, but not when deployed in this slipshod way. Worse, such careless routine deployment actually threatens the concept’s usefulness in conversations where it does offer real insight.

So just what is a network effect? The term describes a product that gets more valuable as more people adopt it, a system that becomes stronger as more nodes are added to the network. The classic example of network effects is a fax machine. The first proud owner of a fax machine has a very expensive paperweight. The second owner can transmit documents to the guy with the pricey paperweight. The thousandth owner has a useful, but limited, piece of equipment. The millionth owner has a pretty handy little gadget.

Megan McArdle, “Facebook Is Big, But Big Networks Can Fall”, Bloomberg View, 2015-10-08.

July 12, 2017

The real newspaper problem is not Facebook and Google … it’s their monopolistic heritage

Tim Worstall argues against allowing US newspapers to have an anti-trust exemption to fight Facebook and Google:

The first thing to note is the influence of geography and transport. By definition a newspaper needs to arrive daily — in physical format least — meaning that there’s a useful radius around a printing plant which can be served. What then happened is exactly what is happening with Google and Facebook, network effects come into play. Each urban area effectively became the monopoly of just the one newspaper. Sure, there were more than that in New York City for example, SF supported two majors later than many other places. But even in such large and rich places we did really only ever end up with one “serious” newspaper.

The network effects stem from the revenue sources. Roughly speaking, you understand, one third came from subscription revenues, one third from display advertising and one third from classifieds. Classifieds are a classic case of said network effects. Everyone advertises where they know everyone reads. Everyone reads the ads where they know everyone advertises those used baby bassinets. Whoever can get ahead in the collection of either then almost always wins the race. Classifieds are also hugely, vastly, profitable.

The way that American newspapers are sold, on subscriptions with a local paper boy, also contains elements of such network effects.

The effect of this economic structure was that each major urban area really had the one monopolist newspaper. This is where that famed “objectivity” comes from too. If there’s going to be the one newspaper then it’s going to try to make sure there’s no room for another by steadily occupying the middle ground on anything and everything. This is just the Hotelling problem all over again. Swing too viciously left or right (on any issue, political, social, whatever) and there might be room for someone to sneak in from the borderlands. Thus the very milquetoast indeed political views at most of these newspapers.

[…]

And that, I insist, is what is really happening to US newspapers. Most certainly, their problems stem from the internet. for the internet broke that monopoly imposed by economic geography and all else stems from that. They got fat and happy within those monopolistic areas and their pain is coming from the adjustments necessary to deal with that. The likely outcome I would expect to be many fewer first line newspapers staffed by many fewer people in much the way that the UK market has worked for near a century now. I would also expect to see them using political stance as a differentiator just as in Britain.