BrainStuff – HowStuffWorks

Published 25 Nov 2014It’s not quite British, and it’s not quite American – so what gives? Why do all those actors of yesteryear have such a distinct and strange accent?

If you’ve ever heard old movies or newsreels from the thirties or forties, then you’ve probably heard that weird old-timey voice.

It sounds a little like a blend between American English and a form of British English. So what is this cadence, exactly?

This type of pronunciation is called the Transatlantic, or Mid-Atlantic, accent. And it isn’t like most other accents – instead of naturally evolving, the Transatlantic accent was acquired. This means that people in the United States were taught to speak in this voice. Historically Transatlantic speech was the hallmark of aristocratic America and theatre. In upper-class boarding schools across New England, students learned the Transatlantic accent as an international norm for communication, similar to the way posh British society used Received Pronunciation – essentially, the way the Queen and aristocrats are taught to speak.

It has several quasi-British elements, such a lack of rhoticity. This means that Mid-Atlantic speakers dropped their “r’s” at the end of words like “winner” or “clear”. They’ll also use softer, British vowels – “dahnce” instead of “dance”, for instance. Another thing that stands out is the emphasis on clipped, sharp t’s. In American English we often pronounce the “t” in words like “writer” and “water” as d’s. Transatlantic speakers will hit that T like it stole something. “Writer”. “Water”.

But, again, this speech pattern isn’t completely British, nor completely American. Instead, it’s a form of English that’s hard to place … and that’s part of why Hollywood loved it.

There’s also a theory that technological constraints helped Mid-Atlantic’s popularity. According to Professor Jay O’Berski, this nasally, clipped pronunciation is a vestige from the early days of radio. Receivers had very little bass technology at the time, and it was very difficult – if not impossible – to hear bass tones on your home device. Now we live in an age where bass technology booms from the trunks of cars across America.

So what happened to this accent? Linguist William Labov notes that Mid-Atlantic speech fell out of favor after World War II, as fewer teachers continued teaching the pronunciation to their students. That’s one of the reasons this speech sounds so “old-timey” to us today: when people learn it, they’re usually learning it for acting purposes, rather than for everyday use. However, we can still hear the effects of Mid-Atlantic speech in recordings of everyone from Katherine Hepburn to Franklin D. Roosevelt and, of course, countless films, newsreels and radio shows from the 30s and 40s.

(more…)

September 13, 2023

Why Do People In Old Movies Talk Weird?

September 11, 2023

Golda Meir

Michael Oren reviews Golda a new biopic on the life of Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir:

Ever since the 1970s, the entrances to many American Jewish institutions have boasted a single bust. It is not of Theodore Herzl, founder of the Zionist movement, or of Israel’s preeminent leader, David Ben-Gurion, nor even of any prominent American Jew — Justice Louis Brandeis or Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel. The likeness is not flattering. Beneath tightly bunned hair, the face is unsmiling, its features decidedly bland. Their owner never graduated college, wrote a transformative book, or commanded an army. Still, that statue embodies an ideal to which most American Jews aspire: at once patriotic yet open-minded, liberal but muscular, courageous and caring. The bust, moreover, is of a woman and not just any woman. With an accent as flat as the Midwestern plains, four packs of unfiltered cigarettes a day and the omnipresent purse that held them, the clunky shoes and grandmotherly attire, she was Everywoman. Yet, in a rags-to-preeminence story so appealing to Americans, that woman rose to become the prime minister of Israel. She was Golda Meir — or, as she’s still colloquially known, simply, Golda.

Until my grandmother’s death at the age of 100, she claimed that the proudest day of her life was hosting Golda for a fundraising event in her Boston home. In 1973, and again in 1974, a Gallup poll named Golda “Woman of the Year”, the only non-American ever to achieve that title, garnering twice as many votes as the runner-up, Betty Ford. Though no feminist — Ben-Gurion once called her “the only man in the government” — she became a poster-child of women’s liberation, appearing under the banner, “But Can She Type?” She served as the subject of two Broadway plays, several documentaries, and a made-for-television movie. Golda characters appear in a variety of productions, from Steven Spielberg’s Munich to season 26, episode 1 of The Simpsons. No fewer than nine English-language biographies have been written about her, in addition to her own memoir, and the recollections of her son. She was — and to a large extent, has remained — an American icon.

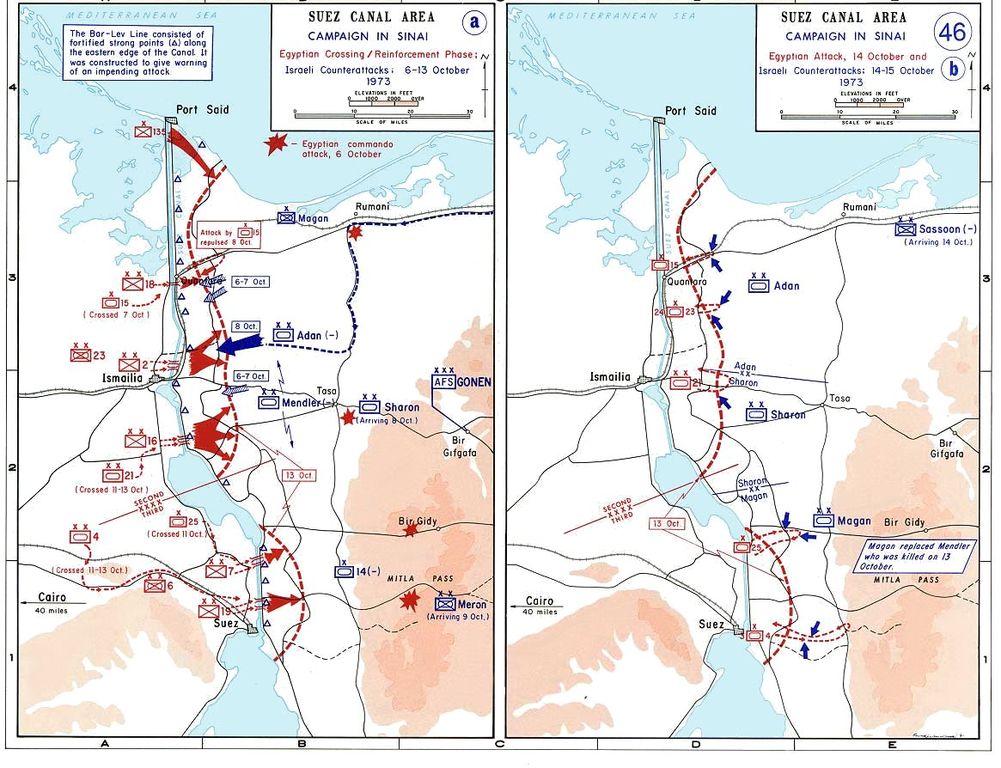

Not so for Israelis. For 50 years, the name Golda has been associated with reckless hubris, with humiliation and trauma and the loss of an innocent Israel that can never be retrieved. Most bitterly, the name Golda evokes the memory of the 2,656 Israeli soldiers — 83 times the number, proportionally, of Americans lost on 9/11 — killed on her watch. Israel has no end of streets and facilities named for Ben-Gurion, for Prime Ministers Levi Eshkol, Yitzhak Rabin, and Menachem Begin, but there are few Golda Meir boulevards or university halls. New York has Golda Meir Square, complete with that unprepossessing bust, but not Tel Aviv or Jerusalem. Only among Israeli children, born long after her death, does Golda elicit any excitement as the name of a popular ice-cream chain.

Now, half-a-century after her purportedly disastrous performance during the 1973 Yom Kippur War, there are attempts to revisit Golda’s legacy, to examine it in the light of recently released documents, and to reflect on the complex human being behind the bust. Spotlighting these revisions is a bold and riveting new film by Academy Award-winning director Guy Nattiv, starring the incomparable Helen Mirren. After portraying Queens Elizabeth I and II and Catherine the Great, Mirren praised her latest character “one of the most extraordinary I’ve ever played.” That estimation is more than illustrated by the movie simply titled Golda.

[…]

Golda Meir remained in her post for another eight months while the people of Israel seethed. Though the Agranat Commission accepted her claim that she acted solely on the defense establishment’s advice and cleared her of any personal responsibility for the war, the population resented the blame placed almost solely on the army. The country, devastated emotionally and economically, was further traumatized by terrorist attacks that killed 52 civilians and wounded 150. Later that year, terrorist leader Yasser Arafat, a holster on his hip, received a standing ovation from the UN General Assembly, which went on to equate Zionism with racism. Succumbing to Arab pressure, 24 of the African countries with which Golda helped establish relations cut ties with Israel. In 1977, the degraded Mapai Party for the first time lost an election to Menachem Begin’s Likud, ending what many Israelis still regard as the state’s golden age.

Such painful events are barely touched upon in either of the Golda films, which prefer to conclude her story with Sadat’s historic visit to Israel in November 1977. The subsequent peace process resulted in the signing of the Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty in 1979, a year after Golda’s death.

Yet her legacy endures — especially now, on the 50th anniversary of the war. Though her standing remains highest in the United States — the Israel National Library reports more searches for her name in English than in Hebrew—in Israel, too, her record is being reconsidered. Here was a woman without military experience who had to rely on men whose expertise on military matters was above reproach. Here was a woman who, when many of those men buckled to pressure, remained clear-headed and strong. And here was a woman who, contrary to long-held wisdoms, repeatedly held out her hand for peace.

Some critics have been unkind to Golda. They take issue with the film’s concentration on her career’s least illustrious period and with the allegedly one-dimensional depiction of a personality known to be compassionate one minute but backbiting the next, alternately maternal and coarse. Most expressed discomfort with the director’s obsession with Golda’s cigarettes — they are practically actors — which earned the film a PG-13 rating for “pervasive smoking”. I, for one, would have liked to see more of Golda’s insecurities about her lack of higher education, military experience, and Hebrew eloquence. I would have welcomed more of the swift-witted Golda who once quipped to Kissinger, arriving in Tel Aviv after exchanging kisses with Egyptian and Syrian leaders, “Why, Mr. Secretary, I didn’t know that you kissed girls, too!”

Nevertheless, Golda must take its place alongside other outstanding portraits of leaders in crisis. Like Gary Oldman’s Churchill in Darkest Hour and Bruce Greenwood’s Kennedy in Thirteen Days, Helen Mirren’s Golda Meir offers a profile of greatness in the face of overwhelming adversity. These are films that, rather than merely report and redramatize facts, show us character. And Golda — the woman, not the myth — should continue to generate our interest as well as our respect. The Everywoman behind the bust should still be revered.

September 6, 2023

“[T]he preemptive hype about [Bottoms] has been fundamentally false, fundamentally dishonest about what constitutes artistic risk and personal risk in 2023″

Freddie deBoer — whose new book just got published — considers the way a new movie is being marketed, as if anything to do with LGBT issues is somehow still “daring” or “risky” or “challenging” to American audiences in the 2020s:

Consider this New York magazine cover story on the new film Bottoms, about a couple of lesbian teenagers (played by 28-year-olds) who start a high school fight club in order to try and get laid. I’m interested in the movie; it looks funny and I’ll watch it with an open mind. Movies that are both within and critiques of the high school movie genre tend to be favorites of mine. But the preemptive hype about it — which of course the creators can’t directly control — has been fundamentally false, fundamentally dishonest about what constitutes artistic risk and personal risk in 2023. The underlying premise of the advance discussion has been that making a high school movie about a lesbian fight club, today, is inherently subversive and very risky. And the thing is … that’s not true. At all. In fact, when I first read the premise of Bottoms I marveled at how perfectly it flatters the interests and worldview of the kind of people who write about movies professionally. As New York‘s Rachel Handler says,

[Bottoms has] had the lesbian Letterboxd crowd, which treats every trailer and teaser release like Gay Christmas, hot and bothered for months. After attending its hit SXSW premiere, comedian Jaboukie Young-White tweeted, “There will be a full reset when this drops.”

And yet to read reviews and thinkpieces and social media, you’d think that Bottoms was emerging into a culture industry where the Moral Majority runs the show. One of the totally bizarre things about contemporary pop culture coverage is that the “lesbian Letterboxd crowd” and subcultures like them — proud and open and loud champions of “diversity” in the HR sense — are prevalent, influential, and powerful, and yet we are constantly to pretend that they don’t exist. To think of Bottoms as inherently subversive, you have to pretend that the cohort that Handler refers to here has no voice, even as its voice is loud enough to influence a New York magazine cover story. This basic dynamic really hasn’t changed in the culture business in a decade, and that’s because the people who make up the profession prefer to think of their artistic and political tastes as permanently marginal even as they write our collective culture.

Essentially the entire world of for-pay movie criticism and news is made up of the kind of people who will stand up and applaud for a movie with that premise regardless of how good the actual movie is. And I suspect that Rachel Handler, the author of that piece, and its editors at New York, and the PR people for the film, and the women who made it, and most of the piece’s readers know that it isn’t brave to release that movie, in this culture, now. And as far as the creators go, that’s all fine; their job isn’t to be brave, it’s to make a good movie! They aren’t obligated to fulfill the expectation that movies and shows about LGBTQ characters are permanently subversive. But the inability of our culture industry to drop that narrative demonstrates the bizarre progressive resistance to recognizing that things change and that liberals in fact control a huge amount of cultural territory.

And here’s the thing: almost everybody in this industry, in media, would understand that narrative to be false, were I to put the case to them this way. This obviously isn’t remotely a big deal — in fact I’ve chosen this piece and topic precisely because it’s not a big deal — and I’m sure most people haven’t thought about it at all. (Why would they?) Still, if I could peel people in professional media off from the pack and lay this case out to them personally, I’m quite certain many of them would agree that this kind of movie is actually guaranteed a great deal of media enthusiasm because of its “representation”, and thus is in fact a very safe movie to release in today’s Hollywood — but they would admit it privately. Because “Anything involving LQBTQ characters or themes is still something that’s inherently risky and daring in the world of entertainment and media, in the year of our lord 2023” is both transparently horseshit and yet socially mandated, in industries in which most people are just trying to hold on and don’t need the hassle.

July 28, 2023

Progressive objections to Oppenheimer

Disclaimer: I haven’t seen the movie, and have no immediate plans to do so. That said, there’s a lot of discussion about the movie, its successes and its failures and how it relates to today’s issues. Over at Founding Questions, Severian felt the need to do a proper fisking of one particularly irritating take:

This is one of two Oppenheimer stories that popped up this morning. I don’t watch tv and haven’t seen a movie in the theater in decades; I doubt I’ve seen more than a handful of “new” movies in the last ten years. So I really am not the target audience for this kind of thing, but … I don’t get it. Why is this movie such a big deal? Have they decided to simply create The One Pop Culture Thing out of whole cloth?

Anyway, let’s see what they have to say:

There’s a cabal online, and even in some professional circles, arguing that Nolan has made the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki a sideshow: that Oppenheimer looks away from the devastating effects of what happened on August 6 and 9 1945.

I guess this is where the Historian in me will forever override the pop culture critic. Obviously Robert Oppenheimer knew he was developing a weapon. The difference between a nuclear bomb and a regular bomb is one of degree, not kind. American firebombing had already done to dozens of Japanese cities what Oppenheimer’s nuke did to Hiroshima. Curtis LeMay knew it, too — after the war, he said that he’d have been rightfully tried for war crimes had the outcome gone the other way. I simply cannot see how this man is uniquely culpable for anything … or if he is, then Rosie the Riveter should be held accountable for every bomber that rolled off the assembly line.

Anti-nuclear groups have been similarly disappointed, with Carol Turner from the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament telling The Guardian that “the effect of the [Hiroshima and Nagasaki] blasts was to remove the skin in a much more gory and horrible way – in [Oppenheimer] it was tastefully, artfully presented.”

That‘s your objection? That people weren’t shown getting killed in a realistic-enough manner? Jesus Christ, do you people ever listen to yourselves? That’s fucking sick. You are a loathsome excuse for a human being, Carol Turner.

Although it says much about the morals and mechanics of war, Oppenheimer isn’t a war film: it’s ultimately about the internal conflict and persecution of one individual. To painstakingly focus on the Japanese victims would have made it an entirely different film, and one at odds with the rest of Nolan’s vision. (His fellow director James Cameron, meanwhile, is said to be planning a film on the victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.)

“Victims”. You keep using that word.

There is currently a trend for great cultural works, such as Oppenheimer, to be denigrated if they don’t tick certain boxes, and such complaints often come from the Left. A lack of focus on victims has been a frequent criticism: it’s an argument that gets wheeled out, for example, whenever a drama is being made about serial killers. Yet I don’t think artists are obliged to do this if it doesn’t fit into their own authorial vision.

I have to admit, I’m getting that old College Town feeling right now. The one where it feels like someone dropped some low-grade acid in my coffee, and I’m hallucinating. I know what all those words mean, but put together like that they don’t make any sense at all. On the most basic level, the objection here seems to be that movies require plots. A “drama about a serial killer”, for example (“drama” … what an odd word choice), requires murders. You know, mechanically speaking. But what does “focusing” on them add? Is it any more or less awful, learning that the dead guy killed at random by a lunatic was really into soccer and had a dog and liked classic rock?

And all this is before you consider that the most vocal critics of Oppenheimer are Leftists … the very same Leftists who are determined to fight to the very last drop of Ukrainian blood, and who seem to think that giving Zelensky tactical nukes is a super idea. Reading the Left’s pronouncements on Vladimir Putin, you’d be forgiven for thinking they’d like to nuke him twice, just to be sure.

Your concern for the “victims” of Hiroshima and Nagasaki rings a little hollow, gang, when you’ve been howling for blood 24/7 on Twitter for a year and a half.

July 17, 2023

QotD: Cavalry combat in Rings of Power versus history

… the scene [in Rings of Power] as a whole seems poorly executed. We’ve gotten some good views of the topography of this village and it is very small. The village is at a three-way road intersection, with the inn at the meeting point on what I am going to call the East side (we see the sun rising over it once and it faces Orodruin); the inn has a small fenced-in area behind it. Beyond that there are four small houses on the road and one further up the hill and the land slopes from high in the north and east to low in the south and west. Finally on the west side there is our small bridge over the stream; a forest directly abuts the village on the south side.

The first thing we see is the cavalry in a great mass riding down into the village with Orodruin clearly behind them; they must be approaching then along the East road. Then we see a 2-horse wide column of cavalry crossing the narrow bridge from the West (at 39:14), then a bunch of orcs gather up into a mass to engage that cavalry force as it gallops up the main road into the village (from 39:16 to 39:26) before getting hit by the vanguard of that column in a really dumb moment we’re going to come back to at 39:30. And now look up at the village above there again and note that it takes one cavalry column at full gallop 16 seconds to go from that bridge to the inn, but the massive wave of cavalry coming over the hill from the other direction has still not managed by this point to actually enter the village proper. They have, apparently, frozen completely solid the moment they were off screen.

So it seems like, while galloping wildly to the rescue of a village they didn’t know was under attack, the Númenóreans also took the time to carefully work their way around the village in order to strike it from two sides at once (somehow filtering through the forest without being noticed, rather than working around the more open terrain to the north side; I cannot communicate clearly enough that cavalry generally avoids moving through forests for a reason), then galloped in at full speed. But the one direction they do not attack from is the North road, which is the only area that is clear and unobstructed (good cavalry ground) and where the slope of the ground is favorable (they’d be charging down hill) with enough space to form up into a proper charge. Instead when we see Galadriel next, she is charging up that hill.

So on the one hand this battle plan doesn’t make any sense, but at the same time I feel I must note just how inferior this is as film-making to the battle scenes in The Lord of the Rings (or even, dare I say it, Game of Thrones). I had to rewatch these scenes, slowly and carefully multiple times to get any sense of where anyone was. By contrast, good battle scenes are careful to make sure the audience understands the geography of the space. Hell, the “battle” scenes in Home Alone are careful to establish the geography of the place (I found the video at that link, by the way, a very approachable introduction to some elements of film study). In The Lord of the Rings we get a lot of big wide shots at high altitude showing us where the armies are in relation to each other […]

Moreover, Peter Jackson’s cavalry doesn’t simply show up. In both of his Big Cavalry Rescues at Helm’s Deep and Minas Tirith he follows the same highly effective pattern of first revealing the presence of the cavalry, then pausing a moment for the cavalry to form up and to give the characters there time for some dialogue and character beats. At Helm’s Deep this is a short exchange between Éomer and Gandalf, while at Minas Tirith it is Théoden’s big defining character moment and speech. From a realism standpoint, it gives the audience time to understand where the cavalry is and how they’ve set up (and a sense that this is organized, planned and prepared).

But this brief delay before “the good stuff” also serves an obviously important emotional narrative aspect that Rings also loses here: it builds anticipation. By the time Théoden is giving his speech outside Minas Tirith, the audience has been waiting for about an hour since the beacons were lit for this very moment of emotional release, waiting for the score to be evened, waiting for the emotional satisfaction of the bad guys getting their come-uppance and so Jackson draws that out just a little bit longer, which builds the anticipation that creates that intense emotional response when the charge at last surges forward. You can even hear the emotions he wants you feel in the music, which starts low and subdued but builds and builds as Théoden sets up his army and gives his speech, booms across the charge itself but then cuts hard to silence in the moment of impact – the moment of greatest suspense (will the charge work?) – before surging back as the charge succeeds, culminating in a big overhead shot showing the good guys winning. It is not historically perfect, but the emotional beats land flawlessly and Rings just fumbles shockingly on both counts.

The resulting melee is also confusing. This village is tiny and while we don’t have a good idea of Adar’s remaining force, it isn’t huge because it seems to all fit in this village which looks to be a fair bit smaller than a regulation soccer pitch. A cavalry charge should be able to run from one side of this road to the other in under 10 seconds (moving at c. 12m/s, a rough horse’s gallop speed); the two leading edges of this charge should be slowing down to meet in the middle in well under five seconds. Consequently the decisive phase of this battle, the one in which orcs are trying to hold the open ground between the buildings (these wide mud streets) should last only seconds, but instead it draws out into a minutes-long melee because, as far as I can tell, the Númenóreans have next to no idea how to fight on horseback.

The thing is, fighting from horseback is quite hard but it is also quite simple. If using stirrups, one’s feet remain in the stirrups pretty much the whole time because the goal here is to retain a firm seat on the horse. Horse archers will sometimes stand up just a little in the stirrups to create a stable firing platform, but only a little bit and at speed an observer may not even notice they are standing at all. But showrunners, it seems, just love putting in all sorts of equestrian tricks; Game of Thrones had to make the Dothraki shoot while standing on the saddle (not a great idea), and so Rings of Power has to do some trick riding. In this case they have Galadriel flip over the side of her horse upside down to slash at an orc while dodging an arrow […]

A close look and you can see that this trick requires a special handhold on her saddle just for the purpose (just like the Game of Thrones standing horse-archers required special trick saddles for that stunt too). And she then cuts an orc’s head off while flipping herself back on to the horse, a sword-stroke that is traveling in the opposite direction of her horse’s movement (it is moving forward, she is swinging backwards), which she cannot brace properly and thus, if it had hit anything but CGI would have been a fairly weak strike; fortunately for Galadriel, CGI orcs are very flimsy so their heads come straight off. The whole thing is a too-clever-by-half effort to look cool, which I also find a bit confusing because Elves don’t seem to me to fight on horseback very often in the Tolkien legendarium; they do it from time to time, but the great elf heroes tend to fight on foot, so it’s not clear to me why Galadriel has to also be the best rider. But that routine is then topped by the baffling idiocy of Valandil here who, despite having a perfectly good sword (though he seems to have lost his spear in the fighting) decides his best plan of attack is to jump off of his horse and tackle two orcs […]

Needless to say a high speed falling dismount is a good way to injure yourself in an actual battle but also that jumping off of your horse is not a good use of you or the horse. Meanwhile the rest of the Númenórean cavalry seem to have mostly come to a stop and are now having stationary fights with orc infantry; some of them get pulled down off of their horses which, yes, is the predictable result of being stupid enough to bring your cavalry to a full stop without of any kind of mutually supporting formation or infantry support. I think many of the problems in this sequence stem from the apparent need to have this seem like a fight that could go either way, when in practice this should have been a short and decisive engagement the moment the cavalry arrived, given that the cavalry is more heavily armored, faster, has the advantage of surprise and presumably outnumbers the orcs given how small the village is. I suppose it might take a bit longer because Adar’s first wave of orcs are hitting their respawn timer so there were adds. Once again the utter inability of the show to keep track of just how many orcs there are ruins any sense of tension but also any hope of the battle making sense; it sure seemed like there were just a few dozen orcs left, which ought to make a battle against 300 armored riders a remarkably short and one-sided affair.

But the moment in this whole fight that broke me completely actually came quite early right after the Númenóreans crossed the bridge. […] I will admit that I burst out laughing when this happened: the horseman ride up in a pair holding on to opposite ends of a chain, which they then use to clothesline about two dozen orcs while steadily fanning out. Once again this is one of those too-clever-by-half Hollywood tactics moments, which defy both physics and logic. The first problem is that I’m not clear on how long this chain is: they need to be holding it tightly or it is just going to snag on the first impact, but they also fan out meaning they need to keep letting out more chain to cover the increasing distance between the two horses. In practice looking at the stills it seems like the chain isn’t under much of any tension at all, which would make it fairly useless as a weapon here – sure a metal chain will have some momentum to it, but not enough to knock multiple ranks of armored troops down.

But of course the broader problem is that if the plan is to merely smash into the orcs with a lot of kinetic force you should just trample them. Putting all of that impact energy in the chain is just going to pull the rider off of their horse since the sole point of contact for that energy is their arms. By contrast, medieval knightly cavalry eventually adopted high-backed saddles, couched lances and lance-rests on their armor all to help keep the knight in his seat through the force of a heavy impact at full speed (cavalry with or without these various devices might need to let their point trail at impact that it wasn’t pulled from their hand but rather the movement of their horse pulled it from their target, a motion pattern easily observed in the modern sport of tent-pegging). But just carrying a chain gives none of these advantages or options: if there’s enough force to knock down a half-dozen orcs, there’s enough force to knock a rider out of his saddle.

Of course in an actual battle this wouldn’t even get this far because the other disadvantage of this chain is that it sacrifice’s the reach of a spear. Now, credit where credit is due, the Númenóreans do seem to have standard issue spears (good!), except for these two guys with the chain (a tactic that only works when advancing two-by-two, which is a terrible way to fight, through a narrow space where cavalry should not be, but nevertheless apparently one the Númenóreans come ready for as standard). No one seems to use their spears on horseback (they shift to swords immediately), but at least they have them. The advantage of a spear or lance of course is that it is a weapon which can project beyond the head of the horse, thus reducing some of the reach advantage an infantryman might have, while concentrating all of the energy of impact at a single point.

But the riders here have to hold this silly chain on their laps, which puts it several feet behind the head of their horse and because it isn’t perfectly taut it lags their motion meaning that it impacts the orcs several feet behind that, which means – as you can see above – the entire horse has to gallop past the target orc before he is hit by the chain. Any any time during that operation that orc could strike at the horse or the rider, spilling them both to the ground and to make the whole thing worse because the riders can’t have a sword or a shield in their hands, they can’t even defend themselves if an orc decides to do this.

Much like the ships, much like the falling tower trap, much like the nonsensical ring forging, it is another instance of the creators attempting to be novel and clever without really understanding the historical practices they are working from. Cavalry tactics, like battle tactics, like ship design, like metalworking, were fields of human endeavor that absorbed the sharpest minds humankind has to offer and persistent experimentation and adaptation for centuries, resulting in highly tested, highly refined patterns of behavior. I will not say that improvement on those practices is impossible, but it would certainly be very hard, the sort of thing which would itself require extensive dedicated study and experimentation. It is not the sort of thing likely to be accomplished in a writer’s room brainstorming session, which is why efforts to “outsmart” the past tend to end up looking silly, rather than clever.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Nitpicks of Power, Part III: That Númenórean Charge”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2023-02-03.

July 5, 2023

The “orgasm gap”, yet another problematic front in the war of the sexes

Janice Fiamengo discusses the faked orgasm scene in When Harry Met Sally and its role in the ongoing arguments over the “orgasm gap”:

An iconic moment in modern movie history is the diner scene from When Harry Met Sally (1989), when Sally stuns an incredulous Harry with her rendition of a convincing orgasm. Her bravura performance causes shocked silence in the restaurant until one woman, sitting nearby, says admiringly (or enviously), “I’ll have what she’s having.”

The scene and the woman’s amused reaction told of a simple reality with wit and without judgement: some portion of women — perhaps many — are convincing fakers, and even a sexually experienced man will find it hard to be sure.

Many women in the movie audience laughed in recognition, and many men likely scratched their heads, wondering why anyone would need to fake sexual enjoyment. Some men may have remembered times when they faked it too. In the romantic-comedic world of the movie, the scene symbolized one of the differences between the average woman and the average man that only a generous and committed love could bridge.

A few years ago, When Harry Met Sally turned 30 years old, and its anniversary prompted a number of reflection pieces, some turning a harsh feminist lens on the film’s gender politics. In “‘I’ll have what she’s having’: How that scene from When Harry Met Sally changed the way we talk about sex,” Lisa Bonos at The Washington Post found in the fake climax scene a salutary revelation of male sexual arrogance. For Bonos, Harry is a typical macho man, someone who doesn’t care about a woman’s pleasure. The fact that the whole point of his conversation with Sally had been his confidence that he was giving women pleasure simply confirmed his emetic masculinity.

According to Bonos, the fact that some women fake orgasm supposedly reveals that women’s sexual pleasure is “not prioritized” in heterosexual relationships, and Sally’s performance gave sobering evidence of a gendered pleasure gap. It was implicitly the man’s fault that his partner felt the need to lie to him about her sexual satisfaction, and his desire for her to orgasm proved his typically male ego. Bonos’s analysis was an egregious violation of the spirit of the movie but was eminently faithful to the feminist perspective. The politics of grievance had come a long way in three decades.

Right on cue, studies in human psycho-sexuality are now taking up the same theme, alleging a culturally imposed “orgasm gap” between men and women in which men outpace women in the frequency with which they report orgasm during sexual intercourse (86% for men vs. 62% for women, according to one national survey).

Remembering how consistently feminist pundits have expressed outrage at male incels‘ (alleged) sense of “entitlement” to sex, I cannot help but find it ironic how unapologetically researchers assume a female entitlement to orgasm. Apparently, the whole society is to be concerned if women fail to climax every time they have sex, while no one has compassion for young men who face a lifetime of sexlessness. The prime exhibit is “Orgasm Equality: Scientific Findings and Societal Implications“, a paper published in 2020 by three female researchers at the University of Florida. The paper not only surveys the literature on the subject but also makes recommendations for “a world of orgasm equality”.

July 4, 2023

Buster Keaton Rides Again (1965)

NFB

Published 15 Jun 2015In this film Keaton rides across Canada on a railway scooter and, between times, rests in a specially appointed passenger coach where he and Mrs. Keaton lived during their Canadian film assignment. This film is about how Buster Keaton made a Canadian travel film, The Railrodder. In this informal study the comedian regales the film crew with anecdotes of a lifetime in show business. Excerpts from his silent slapstick films are shown

Directed by John Spotton – 1965.

June 25, 2023

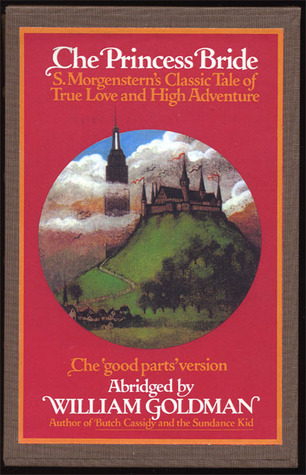

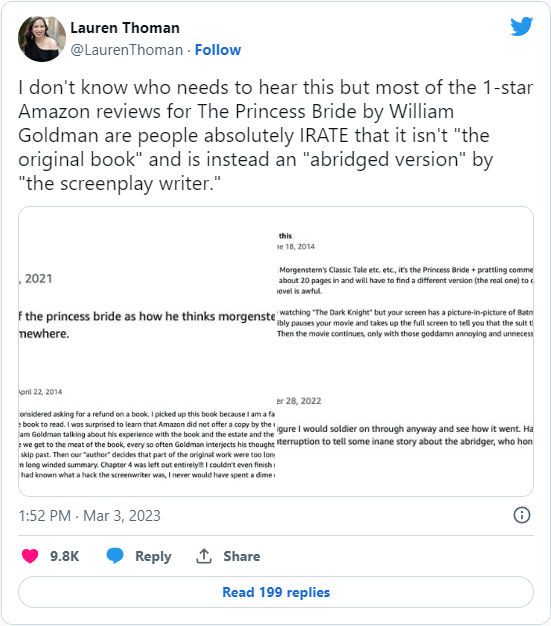

Fifty years after The Princess Bride was published

William Goldman’s novel The Princess Bride was not a blockbuster, nor did the movie adaptation get a huge box office when it released in 1987. Yet despite apparent early mediocrity, it became a cult classic. It’s now fifty years after the book came out, and Kevin Mims has a look back at both the novel and the movie:

Even by the eccentric standards of fantasy literature, William Goldman’s 1973 novel The Princess Bride is extremely odd. The book purports to be an abridged edition of a classic adventure story written by someone named Simon Morgenstern. In a bizarre introduction (more about which in a moment), Goldman claims merely to have acted as editor. Unlike Rob Reiner’s much-loved 1987 film adaptation, the book’s full title is The Princess Bride: S. Morgenstern’s Classic Tale of True Love and High Adventure, The “Good Parts” Version. Yes, all that text actually appeared on the cover of the book’s first hardcover edition (all but the first three words have been scrubbed from the covers of most subsequent editions).

In the 1990s, I worked at a Tower Books store in Sacramento. Every few months, someone would come into the store and ask if we had an unabridged edition of S. Morgenstern’s The Princess Bride. The first time this happened, a younger colleague who had worked there longer than I had told my customer, “The Princess Bride was written by William Goldman. There is no S. Morgenstern. Goldman made him up.” The customer wasn’t convinced. “It’s metafiction,” my colleague explained. “A novel that comments on its own status as a text.” When the customer had left, my colleague told me that a lot of people still believe there is an original version of the novel available somewhere, written by Morgenstern. Having fallen in love with the story via the Hollywood film, they were now looking for the ur-text.

Although I was a big fan of William Goldman, I had never read The Princess Bride. My wife and I saw the film when it first appeared in American theaters, and we have rewatched it several times since on VHS and DVD. Only about 10 years ago did I actually get around to reading the novel. And when I did, I found myself sympathizing with all those people who still believe that, somewhere in the world, there exists an unedited edition.

In his introduction, Goldman tells us that S. Morgenstern was from the tiny European nation of Florin, located somewhere between Germany and Sweden, which is where the story’s action takes place. Such a place never existed, but it’s not surprising that many 21st-century American readers don’t know the names of every current and former European kingdom. European history is littered with microstates that rose briefly and then vanished without leaving much of a trace. Back in the 1990s, before Internet access became commonplace, confirming the existence of a small defunct European statelet would have involved a trip to the library.

But readers in the 1970s might have been more alive to Goldman’s ruse. Back then, metafiction was all the rage. John Barth became a literary superstar (among the academic set, anyway) with books like The Sot-Weed Factor (which, like The Princess Bride, is a fantastical comic adventure supposedly written by a fictional author) and Giles Goat-Boy (the text of which, Barth writes in the foreword, was said to have been written by a computer). In 1983, Goldman would publish a second novel behind the Morgenstern pseudonym, titled The Silent Gondoliers, but this time he removed all mention of himself, even from the copyright page.

June 20, 2023

MAC Operational Briefcase (the H&K We Have at Home)

Forgotten Weapons

Published 3 Mar 2023Note: This video was proactively deleted to avoid a channel strike when YouTube went nuts over suppressors. I am reposting it today since they have rolled back those policy changes.

If a swanky outfit like H&K can make an “Operational Briefcase” with a submachine gun hidden inside it, then you can bet Military Armament Corporation is going to do the same! MAC made these briefcases for both the M10 and M11 submachine guns, and made a shortened suppressor for the M10 pattern guns to fit. They actually have a distinct advantage over the H&K type by fitting a gun with suppressor — but a distinct disadvantage in the exposed trigger bar on the bottom of the case, with no safety device of any kind.

Note: Possession of the briefcase with a semiauto MAC-type pistol that fits it is potentially seen as constructive possession of an AOW. A machine gun can be legally fitted in the case, but a semiauto pistol in it is considered a disguised weapon, and thus requires registration as an AOW.

(more…)

June 12, 2023

Why Modern Movies Suck – The Strong Female Character

The Critical Drinker

Published 10 Jun 2023One of the most tiresome tropes of the past ten years in moviemaking is the “Strong Female Character”. Not women who are smart, capable, well written and complex, but bland, boring, superficially “strong” characters designed to pander to simplistic ideals of female empowerment.

(more…)

QotD: Cities in the pre-modern era

This week and next, we’re going to look at an issue not of battles, but of settings: pre-modern cities – particularly the trope of the city, town or castle set out all alone in the middle of empty spaces. Why does the city or castle-town set amidst a sea of grass feel so off? And what should that terrain look like – especially in how it is shaped by the human activity taking place in a town’s hinterland. This is less of a military history topic (though we’ll see that factors in), and more of an economic history one. If that’s your jam – stay tuned, there will be more. If it’s not – don’t worry, we won’t abandon military topics either.

I find myself interested in pre-modern economies and militaries in roughly equal measure (in part because both are such crucial elements of state or societal success or failure). One of the reasons is that they are so interconnected: how military force is raised, supplied, maintained and projected is deeply dependent on how the underlying economy (which supplies the men, food, weapons and money) is structured and organized. And military institution and activities often play an important role in shaping economic structures in turn. So even if you are just here for the clashing of swords, remember: every sword must be forged, and every swordsman must be fed.

(Additional aside: I am assuming a west-of-the-Indus set of cereals: grain, barley and millet chiefly. Specifically, I am not going to bring in rice cultivation – the irrigation demands and density of rice farming changes a lot (the same is also true, in the opposite direction, to agriculture based around sorghum or yams). Most (western) fantasy and historic dramas are not set in rice-planting regions (and many East Asian works seem to have a much better grasp on where rice fields go and need no correction), so I’m going to leave rice out for now. I’m honestly not qualified to speak on it anyway – it is too different from my own area of research focus, which is on a Mediterranean agricultural mix (wheat, barely, olives, grapes), and I haven’t had the chance to read up on it sufficiently).

Lonely Cities

There’s a certain look that castles and cities in either historical dramas or fantasy settings set in the ancient or medieval world seem to have: the great walls of the city or castle rise up, majestically, from a vast, empty sea of grassland. […] These “lonely cities” are everywhere in fantasy and historical drama. I think we all know something is off here: cities and other large population centers do not simply pop up in the middle of open fields of grass, generally speaking. So if this shouldn’t all be grassland, what should be here? Who should be here?

What is a City For?

I think we need to start by thinking about why pre-modern towns and cities exist and what their economic role is. I’ll keep this relatively brief for now, because this is a topic I’m sure we’ll return to in the future. As modern people, we are used to the main roles cities play in the modern world, some of which are shared by pre-modern cities, and some of which are not. Modern cities are huge production centers, containing in them both the majority of the labor and the majority of the productive power of a society; this is very much not true of pre-modern cities – most people and most production still takes place in the countryside, because most people are farmers and most production is agricultural. Production happens in pre-modern cities, but it comes nowhere close to dominating the economy.

The role of infrastructure is also different. We are also used to cities as the center-point lynch-pins of infrastructure networks – roads, rail, sea routes, fiber-optic cable, etc. That isn’t false when applied to pre-modern cities, but it is much less true, if just because modern infrastructure is so much more powerful than its pre-modern precursors. Modern infrastructure is also a lot more exclusive: a man with a cart might visit a village where the road does not go, but a train or a truck cannot. The Phoenician traders of the early iron age could pull their trade ships up on the beach in places where there was no port; do not try this with a modern container ship. Infrastructure is largely a result of cities, not their original purpose or cause.

So what are the core functions of a pre-modern city? I see five key functions:

- Administrative Center. This is probably the oldest purpose cities have served: as a focal point for political and religious authorities. With limited communications technology, it makes sense to keep that leadership in one place, creating a hub of people who control a disproportionate amount of resources, which leads to

- Defensive/Military Center. Once you have all of those important people and resources (read: stockpiled food) in one place, it makes sense to focus defenses on that point. It also makes sense to keep – or form up – the army where most of the resources and leaders are. People, in turn, tend to want to live close to the defenses, which leads to

- Market Center. Putting a lot of people and resources in one place makes the city a natural point for trade – the more buyers and sellers in one place, the more likely you are to find the buyer or seller you want. As a market, the city experiences “network” effects: each person living there makes the city more attractive for others. Still, it is important to note: the town is a market hub for the countryside, where most people still live. Which only now leads to

- Production Center. But not big industrial production like modern cities. Instead it is the small, niche production – the sort of things you only buy once-in-a-while or only the rich buy – that get focused into cities. Blacksmiths making tools, producers of fine-ware and goods for export, that sort of thing. These products and producers need big markets or deep pockets to make end meet. The majority of the core needs of most people (things like food, shelter and clothes) are still produced by the peasants, for the peasants, where they live, in the country. Still, you want to produce goods made for sale rather than personal use near the market, and maybe sell them abroad, which leads to

- Infrastructure Center. With so much goods and communications moving to and from the city, it starts making sense for the state to build dedicated transit infrastructure (roads, ports, artificial harbors). This infrastructure almost always begins as administrative/military infrastructure, but still gets used to economic ends. Nevertheless, this comes relatively late – things like the Persian Royal Road (6th/5th century BC) and the earliest Roman roads (late 4th century BC) come late in most urban development.

Of course, all of these functions depend, in part, on the city as a concentration of people. but what I want to stress – before we move on to our main topic – is that in all of these functions the pre-modern city effectively serves the countryside, because that is still where most people are and where most production (and the most important production – food) is. The administration in the city is administering the countryside – usually by gathering and redistributing surplus agricultural production (from the countryside!). The defenses in the city are meant to defend the production of the countryside and the people of the countryside (when they flee to it). The people using the market – at least until the city grows very large – are mostly coming in from the country (this is why most medieval and ancient markets are only open on certain days – for the Romans, this was the “ninth day”, the Nundinae – customers have to transit into town, so you want everyone there on the same day).

(An aside: I have framed this as the city serving the economic needs of the countryside, but it is equally valid to see the city as the exploiter of the countryside. The narrative above can easily be read as one in which the religious, political and military elite use their power to violently extract surplus agricultural production, which in turn gives rise to a city that is essentially a parasite (this is Max Weber’s model for a “consumer city”) that contributes little but siphons off the production of the countryside. The study of ancient and medieval cities is still very much embroiled in a debate between those who see cities as filling a valuable economic function and those who see them as fundamentally exploitative and rent-seeking; I fall among the former, but the latter do have some very valid points about how harshly and exploitatively cities (and city elites) could treat their hinterlands.)

Consequently, the place and role of almost every kind of population center (city, town or castle-town) is dictated by how it relates to the countryside around it (the city’s hinterland; the Greeks called this the city’s khora (χώρα)).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Lonely City, Part I: The Ideal City”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-07-12.

June 5, 2023

The Longest Day: 75 Things You Don’t Need to Know

A Million Movies

Published 6 Jun 2019In honor of the 75th anniversary of the D-Day invasion, I’m taking a look at my favorite D-Day movie … The Longest Day.

Also, unlike most of my other videos, there are some things in here I think you do need to know. Number one on that list is to hear some of the true stories of the men and women featured in this movie. They, along with hundreds of thousands of other heroes and heroines, saved the world.

Fair warning: My pronunciation of anything French is going to be amazingly bad. No disrespect intended.

June 2, 2023

A potential sign of resistance?

Severian on the odd phenomena of people who’ve begun to discover they didn’t need to accept the ever-more-woke products of the entertainment industry and, more recently, major retailers and brewers:

The Third Law of SJW — “SJWs always double down” — is really going to get tested with these things [woke reboots/remakes of popular TV shows, movies, etc.], but we need to hope they keep the faith. We want them to double, triple, quadruple down. The material basis of Clown World is the assumption that people simply can’t live without iCrap. As I noted, lots of people did indeed seem to enjoy the Covid lockdowns, and they weren’t all aspiring Laptop Class leftoids, either. Lots of moms found out that they rather enjoyed spending time with their kids, rather than putting in an extra twenty hours a week down at the law firm. Lots of suburban dads found a new sense of accomplishment doing little projects around the house.

In other words, people found out that not only could they just “make do”, they actually kinda enjoyed “making do”. Lots of them went right back to their old ways the minute they could, of course, but not all of them … and now, #Woke Capital is basically doing the job for us. They’re daring us to not go to the movies, the same way Fox News is daring us to cut the cord entirely (they figure that hey, we get $x a month from the cable subscription fee regardless of whether anyone watches or not, so why not give in to our natural inclinations and become MSNBC Lite?).

They’re daring us to cut the cord, throw the Pocket Moloch in the nearest lake, and get what we need from local sources — including entertainment. And who knows what might happen if we start actually talking to our neighbors? If, as with the lockdowns, the guy who lives down the street ceases to be “the dude with the green Honda” and becomes Bob, a real person?

Challenge accepted, motherfuckers.

May 25, 2023

QotD: How long does “celebrity” last?

The first warning sign was when they renamed Bob Hope Airport.

Back in the 1940s, Bob Hope was the most popular comedian in the world. He was a radio star. He was a movie star. He would later become a TV star at NBC.

When Hope died in 2003, it made perfect sense to name the Burbank airport after him. After all, his longtime employer NBC was the best known company in Burbank, and Bob Hope had spent a half-century on the network — usually at the top of the ratings.

So the local airport got renamed.

But the only thing that lasts forever in pop culture is the fact that nothing last forever. By 2017, Bob Hope was only a dim memory at NBC, and young passengers flying to SoCal had no idea who he was. So they changed the name to the Hollywood Burbank Airport.

By coincidence this happened almost exactly 80 years after Hope rose to fame — when Paramount signed him to star in the film The Big Broadcast of 1938. In that hit movie, he sang his charming theme song “Thanks for the Memories” — which he kept singing until the end of the 20th century. Not long ago, everybody knew that song.

But then the memories ran dry.

I’ve long believed that 80 years is a typical span of pop culture fame for superstars. I’m referring to the biggest names — the lesser stars burn out in 80 months or 80 weeks or 80 days. But the top draws retain their fame for the entire lifetime of their youngest fans — and given current life expectancies of the US audience, that can’t be much more than 80 years.

We already see the price of Elvis Presley memorabilia starting to drop. The recent Elvis biopic might slow the erosion, but will never bring back the King’s red hot fame of the 1950s. By my measure, Elvismania will be officially dead in the year 2034. That will be the 80th anniversary of his first hit single “That’s All Right”. Almost none of his original audience will still be around to celebrate the anniversary, and that can’t bode well, even for the nostalgia crowd.

Some reputations do flourish after 80 years, but only because the entertainers somehow found an audience outside of pop culture. Louis Armstrong was famous as an entertainer during his lifetime, but enjoys posthumous renown as an artistic and cultural figure. Back in the 1920s, Rudy Vallée sold more records than Armstrong, but never made the transition outside of pop culture.

Ted Gioia, “How Long Does Pop Culture Stardom Last?”, The Honest Broker, 2023-02-23.

May 23, 2023

QotD: Cavalry operations in Rings of Power versus cavalry operations in history

Now before I lay into this, fair is fair: Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings had a real habit of having the horses almost always move at the trot or the canter when they ought to have been walking (horses have four “gaits” – patterns of moving – which, in escalating speed are the walk, the trot, the canter and the gallop). Horses can walk or trot for long periods, but canters and gallops can only be maintained in short bursts before the horse wears itself out. So for instance when Théoden leads the Rohirrim from Edoras in Return of the King the horses are walking in the city but by the time they’re in column out of the city the whole column is moving at a canter (interestingly, you can hear the three-beat pattern of the canter in the foley, which is some attention to detail), which is not realistic – they have a long way to go and they won’t be able to maintain this gait the whole way – but fits the forward momentum of the scene. Likewise most of the horses look to be at a canter when his army leaves Dunharrow for Gondor; again this is a bit silly, but on roughly the level of silly of having Aragorn, Legolas and Gimli pursue a band of orcs by jogging for three days and nights without rest.

By contrast [in Rings of Power], the Númenóreans rush to the battle at a full gallop, apparently the whole way or at the very least for hours through the morning. Horses will be vary, but generally two to three miles is the maximum distance most horses can gallop before fatigue sets in (for most horses this distance is going to be shorter), which they’re going to cover in about six minutes. The gallop is a very fast (25-30mph), very short sprint, yet Galadriel has this whole formation at full gallop even before she can see their destination. And I just want to remember here the absurdity that these horsemen do not even know there is a battle to ride to; for all they know this is a basic scouting effort (which might be better accomplished slowly and without wearing down all of the horses). Théoden at least has the excuse that he’s on the clock and knows it!

The way we are then shown the cavalry arriving is very confusing to me. The speed of their arrival makes at least some sense. We have already established that both Arondir and Adar are incompetent commanders so the fact that they have set no scouts or lookouts checks out. Pre-modern and early-modern cavalry could effectively out-ride news of their coming, and so show up unexpectedly in places with very little warning. Not this little warning, mind you – the time from the first sound of hoof-falls (heard by Elves – the orcs evidently hear nothing) to the cavalry deluging the village is just about fifteen seconds; horses move fast but they do not move that fast (at full gallop a horse might cover 150-200 meters in those fifteen seconds and the orcs would absolutely hear them coming before they saw them). But the idea in general that the Númenórean cavalry could appear as if out of nowhere to the orcs checks out – that was one of the major advantages of cavalry operations.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Nitpicks of Power, Part III: That Númenórean Charge”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2023-02-03.