Last year I rejoined the ranks of the spouse-free. Things sure changed since the last time I was single.

For starters, it is not necessary for men to ask women for revealing selfies. Those photos just start showing up on your phone after you exchange numbers. A revealing selfie in 2014 is essentially just a digital business card for your dating life.

I have also discovered that the most-used characters on my phone keyboard are emoticons. When single people text each other, every sentence has to end with an exclamation mark or a smiley emoticon or else it looks like you lost interest since the last time you texted thirty seconds ago.

For the most part, texting is just a means of feeling connected at a distance. The content isn’t terribly important. But the pauses between text messages mean A LOT. Single people monitor the pauses between text replies to decipher real meaning in the content. For example, if I text “I really enjoyed our time together,” the real message is contained in the timing of the message not the content. If the text is sent while one person is still driving home from a date, that means you feel a strong connection. But if I text something nice and have to wait seven hours for a reply, the seven-hour wait is the message, not the content of the reply.

Single people in 2014 frequently break up with each other by text, but the words are only the punctuation at the end of the break up. The actual break-up happens with what is called “the taper.” The taper is when you are texting someone at a predictable rate, such as several times per day, and you gradually reduce your texting to one message every third day. That’s the taper, and it tells the other person your interest has tapered too.

Scott Adams, “The Tyranny of Expectations”, Scott Adams Blog, 2014-11-24.

December 5, 2015

QotD: The modern dating scene … and texting

November 27, 2015

A different view of Uber and other ride-sharing services

Robert Tracinski on Uber as a form of “Objectivist LARP“:

If it sometimes seems like it’s impossible to restore the free market, as if every new wave of government regulation is irreversible, then consider that one form of regulation, which is common in the most dogmatically big-government enclaves in the country, is being pretty much completely dismantled before our eyes. And it’s the hippest thing ever.

I was reminded of this by a recent report about yet another attempt to help traditional taxis compete with “ride-sharing” services like Uber and Lyft: a new app called Arro, which allows you to both hail a traditional taxi and pay for it from your phone. So Arro takes a twentieth-century business and finally drags into the twenty-first century. This certainly might help improve the taxi experience relative to how things were done before. But it won’t fend off Uber and Lyft, because it doesn’t change the central issues, which are political rather than technological.

[…]

Uber has been hit with complaints that it’s running “an Objectivist LARP,” a live-action role playing of a capitalist utopia from an Ayn Rand novel. That’s pretty much what it is doing, and the results are awesome. And the benefits don’t stop with more drivers and lower rates. Uber is ploughing a fair portion of its profits into another wave of technological innovation—self-driving cars—that promises to offer even greater improvements in the future.

All of this should counter some of the despair about how to promote free markets, especially among urban elites who have been programmed by their college educations to embrace the rhetoric of the Left. Give them half a chance, and they will flock to capitalist innovations run according to the laws of the market.

The problem is that they don’t want to admit it. That’s where the euphemism “ride-sharing” comes in. To cover up the capitalistic nature of the activity, they tell themselves they’re “sharing” something that they are quite obviously paying for, and paying at market rates. Imagine what could be accomplished if they were just willing to drop the euphemisms and embrace the free market.

November 23, 2015

Do you have a smartphone? Do you watch TV? You might want to reconsider that combination

At The Register, Iain Thomson explains a new sneaky way for unscrupulous companies to snag your personal data without your knowledge or consent:

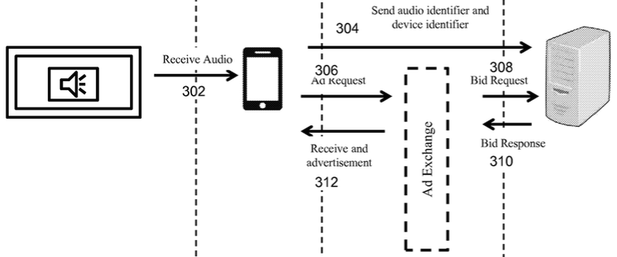

Earlier this week the Center for Democracy and Technology (CDT) warned that an Indian firm called SilverPush has technology that allows adverts to ping inaudible commands to smartphones and tablets.

Now someone has reverse-engineered the code and published it for everyone to check.

SilverPush’s software kit can be baked into apps, and is designed to pick up near-ultrasonic sounds embedded in, say, a TV, radio or web browser advert. These signals, in the range of 18kHz to 19.95kHz, are too high pitched for most humans to hear, but can be decoded by software.

An application that uses SilverPush’s code can pick up these messages from the phone or tablet’s builtin microphone, and be directed to send information such as the handheld’s IMEI number, location, operating system version, and potentially the identity of the owner, to the application’s backend servers.

Imagine sitting in front of the telly with your smartphone nearby. An advert comes on during the show you’re watching, and it has a SilverPush ultrasonic message embedded in it. This is picked up by an app on your mobile, which pings a media network with information about you, and could even display followup ads and links on your handheld.

“This kind of technology is fundamentally surreptitious in that it doesn’t require consent; if it did require it then the number of users would drop,” Joe Hall, chief technologist at CDT told The Register on Thursday. “It lacks the ability to have consumers say that they don’t want this and not be associated by the software.”

Hall pointed out that very few of the applications that include the SilverPush SDK tell users about it, so there was no informed consent. This makes such software technically illegal in Europe and possibly in the US.

July 13, 2015

Do photographers have any rights left?

I no longer do much in the way of “serious” photography (my digital SLR has been out of service for a couple of years now), but I still occasionally do a bit of cellphone photography when the occasion arises. On the byThom blog, Thom Hogan provides a long (yet not exhaustive) list of things, places, and people who are legally protected from being photographed in various jurisdictions … and it gets worse:

Funny thing is, smartphones are so ubiquitous and so small, many of those bans just aren’t enforceable against them in their natural state (e.g., without selfie stick), especially if they’re used discriminatingly.

I’m all for privacy, but privacy doesn’t exist in public spaces as far as I’m concerned. Indeed, I’d argue that even in private spaces (malls, for example), that if you’re open for and soliciting business to the public, you’re a public space. As for Copyright, placing artwork in open public spaces (e.g. Architecture) probably ought to convey some sort of Fair Use right to the public, though in Europe we’re seeing just the opposite start to happen. FWIW, I no longer visit and thus don’t photograph in two countries because of national laws regarding photography. Be careful what you wish for, Mr. Bureaucracy; laws often have unintended consequences. As in reducing my interest in visiting your country.

About half of this site’s readers actively practice some form of travel photography, either during vacations or while traveling for business. Note how many of the restrictions on photography start to apply against those that are traveling (locally or farther afield). It’s always easy to impose laws on people who don’t vote for you. it’s why rental car and hotel room taxes are so high, after all.

What prompted this article, though, wasn’t any of the latest photography ban talk, though. Here in Pennsylvania we have fairly restrictive regulations on “recording” another person (e.g. conversations, phone calls, meetings, etc.). In some states, it only takes one party to consent for a recording to be legal. Here in Pennsylvania it takes all parties to consent to being recorded.

H/T to Clive for the link.

February 23, 2015

The “Internet of Things” (That May Or May Not Let You Do That)

Cory Doctorow is concerned about some of the possible developments within the “Internet of Things” that should concern us all:

The digital world has been colonized by a dangerous idea: that we can and should solve problems by preventing computer owners from deciding how their computers should behave. I’m not talking about a computer that’s designed to say, “Are you sure?” when you do something unexpected — not even one that asks, “Are you really, really sure?” when you click “OK.” I’m talking about a computer designed to say, “I CAN’T LET YOU DO THAT DAVE” when you tell it to give you root, to let you modify the OS or the filesystem.

Case in point: the cell-phone “kill switch” laws in California and Minneapolis, which require manufacturers to design phones so that carriers or manufacturers can push an over-the-air update that bricks the phone without any user intervention, designed to deter cell-phone thieves. Early data suggests that the law is effective in preventing this kind of crime, but at a high and largely needless (and ill-considered) price.

To understand this price, we need to talk about what “security” is, from the perspective of a mobile device user: it’s a whole basket of risks, including the physical threat of violence from muggers; the financial cost of replacing a lost device; the opportunity cost of setting up a new device; and the threats to your privacy, finances, employment, and physical safety from having your data compromised.

The current kill-switch regime puts a lot of emphasis on the physical risks, and treats risks to your data as unimportant. It’s true that the physical risks associated with phone theft are substantial, but if a catastrophic data compromise doesn’t strike terror into your heart, it’s probably because you haven’t thought hard enough about it — and it’s a sure bet that this risk will only increase in importance over time, as you bind your finances, your access controls (car ignition, house entry), and your personal life more tightly to your mobile devices.

That is to say, phones are only going to get cheaper to replace, while mobile data breaches are only going to get more expensive.

It’s a mistake to design a computer to accept instructions over a public network that its owner can’t see, review, and countermand. When every phone has a back door and can be compromised by hacking, social-engineering, or legal-engineering by a manufacturer or carrier, then your phone’s security is only intact for so long as every customer service rep is bamboozle-proof, every cop is honest, and every carrier’s back end is well designed and fully patched.

December 12, 2014

Supreme Court swings and misses on cellphone privacy ruling

Michael Geist on the most recent Supreme Court of Canada ruling on the ability of the police to conduct warrantless searches of cellphones taken during an arrest:

The Supreme Court of Canada issued its decision in R. v. Fearon today, a case involving the legality of a warrantless cellphone search by police during an arrest. Given the court’s strong endorsement of privacy in recent cases such as Spencer, Vu, and Telus, this seemed like a slam dunk. Moreover, the U.S. Supreme Court’s June 2014 decision in Riley, which addressed similar issues and ruled that a warrant is needed to search a phone, further suggested that the court would continue its streak of pro-privacy decisions.

To the surprise of many, a divided court upheld the ability of police to search cellphones without a warrant incident to an arrest. The majority established some conditions, but ultimately ruled that it could navigate the privacy balance by establishing some safeguards with the practice. A strongly worded dissent disagreed, noting the privacy implications of access to cellphones and the need for judicial pre-authorization as the best method of addressing the privacy implications.

The majority, written by Justice Cromwell (joined by McLachlin, Moldaver, and Wagner), explicitly recognizes that cellphones are the functional equivalent of computers and that a search may constitute a significant intrusion of privacy. Yet the majority cautions that not every search is a significant intrusion. It ultimately concludes that there is the potential for a cellphone search to be intrusive, it does not believe that that will be the case in every instance.

Given that conclusion, it is prepared to permit cellphone searches that are incident to arrest provided that the law is modified with some additional protections against invasion of privacy. It proceeds to effectively write the law by creating four conditions: a lawful arrest, the search is incidental to the arrest with a valid law enforcement purpose, the search is tailored or limited to the purpose (i.e., limited to recent information), and police take detailed notes on what they have examined and how the phone was searched.

November 13, 2014

Where’s the rimshot?

Marc Wilson posted this to the Lois McMaster Bujold mailing list (off-topic, obviously):

Apparently the inventor of predictive text has died.

His funfair will be on Sundial.

November 12, 2014

An honest, unbiased review of the iPhone 6+ by a guy who owns Apple stock

Scott Adams relates his quasi-religious experience with the latest iPhone:

The experience of getting the iPhone 6 Plus was like getting a puppy. From my first touch of the sleek, sexy miracle of technology I was hooked. I loved it before I even charged it up.

It was large in my hand, and slippery to hold, but I didn’t mind. That would be like complaining that my newborn baby was too heavy. This phone is pure art and emotion frozen in a design genius so subtle that competitors probably can’t even duplicate it. It was pure beauty. Sometimes I found myself just staring at it on the desk because I loved it so. Oh, and it works well too.

But I needed a case. I tried to imagine my anguish if I accidentally dropped this new member of my family and cracked it. I needed protection.

So I went to the Verizon store and bought the only cover they had left that doesn’t look like a six-year old girl’s bedroom wall. The color of my new case could best be described as Colonoscopy Brown. It is deeply disturbing. But because I love my iPhone 6 Plus, and want to keep it safe, I put it on.

Now my phone is not so much a marvel of modern design. Nor would I say it is nourishing my soul with beauty and truth the way it did when naked.

Now it just looks like a Picasso that three hundred homeless people pooped on. You know there’s something good under there but it is hard to care. Now when I see my hideous phone on my desk I sometimes think I can hear Siri beg me “Look away! Look away!”

[…]

Beauty needs to be temporary to be appreciated. I think those magnificent bastards at Apple know that. I think they made the case slippery by design. They want you to know that if you keep your phone selfishly naked, and try to hoard the beauty that is designed to be temporary, that phone will respond by slipping out of your hand and flying to its crackly death on a sidewalk.

November 6, 2014

Apple is working really hard to keep their customers

… but not necessarily in a good way:

Here is what they never tell you — Apple has devised a very clever way to make leaving the iOS world really, really painful. Specifically, when you send a text message on an iPhone, unless you fiddled with the default settings, it gets sent through iMessage and the Apple servers. If it is going to another iPhone, it can actually bypass the carrier text messaging system altogether, a nice perk back when texts were not unlimited but useful today mainly for international travel.

But here is the rub — when you switch you phone line away from an iPhone to an Android device, the Apple servers refuse to recognize this. They will think you still have an iPhone and will still try to send you messages via the iMessage servers. What this means in practice is that you can send messages from the new phone to other iPhones, but their texts back to you will not reach you. They just sort of disappear into the ether, and will try forever to be delivered to your now non-existent iPhone.

October 24, 2014

QotD: Poverty in the West is not like poverty in the rest of the world

What is it, in terms of physical goods and services, that we wish to provide for the poor that they do not already have? Their lives often may not be very happy or stable, but the poor do have a great deal of stuff. Conservatives can be a little yahoo-ish on the subject, but do consider for a moment the inventory of the typical poor household in the United States: at least one car, often two or more, air conditioning, a couple of televisions with cable, DVD player, clothes washer and dryer, cellphones, etc. As Robert Rector and Rachel Sheffield report: “The home of the typical poor family was not overcrowded and was in good repair. In fact, the typical poor American had more living space than the average European. The typical poor American family was also able to obtain medical care when needed. By its own report, the typical family was not hungry and had sufficient funds during the past year to meet all essential needs. Poor families certainly struggle to make ends meet, but in most cases, they are struggling to pay for air conditioning and the cable-TV bill as well as to put food on the table.” They also point out that there’s a strong correlation between having boys in the home and having an Xbox or another gaming system.

In terms of physical goods, what is it that we want the poor to have that they do not? A third or fourth television?

Partly, what elites want is for the poor to have lives and manners more like their own: less Seven-Layer Burrito, more Whole Foods; less screaming at their kids in the Walmart parking lot and more giving them hideous and crippling fits of anxiety about getting into the right pre-kindergarten. Elites want for the poor to behave themselves, to stop being unruly and bumptious, to get over their distasteful enthusiasms, their bitter clinging to God and guns. Progressive elites in particular live in horror of the fact that poor people tend to suffer disproportionately from such health problems as obesity and diabetes, and that they do not take their social views from Chris Hayes — and these two phenomena are essentially the same thing in their minds. Consider how much commentary from the Left about the Tea Party has consisted of variations on: “Poor people are gross.”

A second Xbox is not going to change that very much.

Kevin D. Williamson, “Welcome to the Paradise of the Real: How to refute progressive fantasies — or, a red-pill economics”, National Review, 2014-04-24

October 13, 2014

Statistical sleight-of-hand on the dangers of texting while driving

Philip N. Cohen casts a skeptical eye at the frequently cited statistic on the dangers of texting, especially to teenage drivers. It’s another “epidemic” of bad statistics and panic-mongering headlines:

Recently, [author and journalist Matt] Richtel tweeted a link to this old news article that claims texting causes more fatal accidents for teenagers than alcohol. The article says some researcher estimates “more than 3,000 annual teen deaths from texting,” but there is no reference to a study or any source for the data used to make the estimate. As I previously noted, that’s not plausible.

In fact, 2,823 teens teens died in motor vehicle accidents in 2012 (only 2,228 of whom were vehicle occupants). So, my math gets me 7.7 teens per day dying in motor vehicle accidents, regardless of the cause. I’m no Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times journalist, but I reckon that makes this giant factoid on Richtel’s website wrong, which doesn’t bode well for the book.

In fact, I suspect the 11-per-day meme comes from Mother Jones (or whoever someone there got it from) doing the math wrong on that Newsday number of 3,000 per year and calling it “nearly a dozen” (3,000 is 8.2 per day). And if you Google around looking for this 11-per-day statistic, you find sites like textinganddrivingsafety.com, which, like Richtel does in his website video, attributes the statistic to the “Institute for Highway Safety.” I think they mean the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, which is the source I used for the 2,823 number above. (The fact that he gets the name wrong suggests he got the statistic second-hand.) IIHS has an extensive page of facts on distracted driving, which doesn’t have any fact like this (they actually express skepticism about inflated claims of cell phone effects).

[…]

I generally oppose scare-mongering manipulations of data that take advantage of common ignorance. The people selling mobile-phone panic don’t dwell on the fact that the roads are getting safer and safer, and just let you go on assuming they’re getting more and more dangerous. I reviewed all that here, showing the increase in mobile phone subscriptions relative to the decline in traffic accidents, injuries, and deaths.

That doesn’t mean texting and driving isn’t dangerous. I’m sure it is. Cell phone bans may be a good idea, although the evidence that they save lives is mixed. But the overall situation is surely more complicated than the TEXTING-WHILE-DRIVING EPIDEMIC suggests. The whole story doesn’t seem right — how can phones be so dangerous, and growing more and more pervasive, while accidents and injuries fall? At the very least, a powerful part of the explanation is being left out. (I wonder if phones displace other distractions, like eating and putting on make-up; or if some people drive more cautiously while they’re using their phones, to compensate for their distraction; or if distracted phone users were simply the worst drivers already.)

September 24, 2014

QotD: Privacy and cell phones

People who were charged with a crime in England used to be told by the police that they did not have to say anything, but that anything they did say might be taken down and used as evidence against them. I think we should all be given this warning whenever we use a mobile telephone.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Nowhere to Hide”, Taki’s Magazine, 2014-02-23

August 15, 2014

QotD: Mobile phone companies

I recently cancelled a contract with a different provider after some gizmo broke. The company first told me the whole thing was my problem, then at the last moment offered me hundreds of pounds to stay. When your phone company starts using the playbook of an emotionally abusive spouse, this is not a market in good working order.

Tim Harford, “Casinos’ worrying knack for consumer manipulation: The spread of machine gambling offers a portent of other economic developments”, TimHarford.com, 2014-01-07

July 15, 2014

The sheer difficulty of obtaining a warrant

Tim Cushing wonders why we don’t seem to sympathize with the plight of poor, overworked law enforcement officials who find the crushing burden of getting a warrant for accessing your cell phone data to be too hard:

You’d think approved warrants must be like albino unicorns for all the arguing the government does to avoid having to run one by a judge. It continually acts as though there aren’t statistics out there that show obtaining a warrant is about as difficult as obeying the laws of thermodynamics. Wiretap warrants have been approved 99.969% of the time over the last decade. And that’s for something far more intrusive than cell site location data.

But still, the government continues to argue that location data, while possibly intrusive, is simply Just Another Business Record — records it is entitled to have thanks to the Third Party Doctrine. Any legal decision that suggests even the slightest expectation of privacy might have arisen over the past several years as the public’s relationship with cell phones has shifted from “luxury item/business tool” to “even grandma has a smartphone” is greeted with reams of paper from the government, all of it metaphorically pounding on the table and shouting “BUSINESS RECORDS!”

When that fails, it pushes for the lower bar of the Stored Communications Act [PDF] to be applied to its request, dropping it from “probable cause” to “specific and articulable facts.” The Stored Communications Act is the lowest bar, seeing as it allows government agencies and law enforcement to access electronic communications older than 180 days without a warrant. It’s interesting that the government would invoke this to defend the warrantless access to location metadata, seeing as the term “communications” is part of the law’s title. This would seem to imply what’s being sought is actual content — something that normally requires a higher bar to obtain.

Update: Ken White at Popehat says warrants are not particularly strong devices to protect your liberty and lists a few distressing cases where warrants have been issued recently.

We’re faced all the time with the ridiculous warrants judges will sign if they’re asked. Judges will sign a warrant to give a teenager an injection to induce an erection so that the police can photograph it to fight sexting. Judges will, based on flimsy evidence, sign a warrant allowing doctors to medicate and anally penetrate a man because he might have a small amount of drugs concealed in his rectum. Judges will sign a warrant to dig up a yard based on a tip from a psychic. Judges will kowtow to an oversensitive politician by signing a warrant to search the home of the author of a patently satirical Twitter account. Judges will give police a warrant to search your home based on a criminal libel statute if your satirical newspaper offended a delicate professor. And you’d better believe judges will oblige cops by giving them a search warrant when someone makes satirical cartoons about them.

I’m not saying that warrants are completely useless. Warrants create a written record of the government’s asserted basis for an action, limiting cops’ ability to make up post-hoc justifications. Occasionally some prosecutors turn down weak warrant applications. The mere process of seeking a warrant may regulate law enforcement behavior soomewhat.

Rather, I’m saying that requiring the government to get a warrant isn’t the victory you might hope. The numbers — and the experience of criminal justice practitioners — suggests that judges in the United States provide only marginal oversight over what is requested of them. Calling it a rubber stamp is unfair; sometimes actual rubber stamps run out of ink. The problem is deeper than court decisions that excuse the government from seeking warrants because of the War on Drugs or OMG 9/11 or the like. The problem is one of the culture of the criminal justice system and the judiciary, a culture steeped in the notion that “law and order” and “tough on crime” are principled legal positions rather than political ones. The problem is that even if we’d like to see the warrant requirement as interposing neutral judges between our rights and law enforcement, there’s no indication that the judges see it that way.

July 10, 2014

Throwing a bit of light on security in the “internet of things”

The “internet of things” is coming: more and more of your surroundings are going to be connected in a vastly expanded internet. A lot of attention needs to be paid to security in this new world, as Dan Goodin explains:

In the latest cautionary tale involving the so-called Internet of things, white-hat hackers have devised an attack against network-connected lightbulbs that exposes Wi-Fi passwords to anyone in proximity to one of the LED devices.

The attack works against LIFX smart lightbulbs, which can be turned on and off and adjusted using iOS- and Android-based devices. Ars Senior Reviews Editor Lee Hutchinson gave a good overview here of the Philips Hue lights, which are programmable, controllable LED-powered bulbs that compete with LIFX. The bulbs are part of a growing trend in which manufacturers add computing and networking capabilities to appliances so people can manipulate them remotely using smartphones, computers, and other network-connected devices. A 2012 Kickstarter campaign raised more than $1.3 million for LIFX, more than 13 times the original goal of $100,000.

According to a blog post published over the weekend, LIFX has updated the firmware used to control the bulbs after researchers discovered a weakness that allowed hackers within about 30 meters to obtain the passwords used to secure the connected Wi-Fi network. The credentials are passed from one networked bulb to another over a mesh network powered by 6LoWPAN, a wireless specification built on top of the IEEE 802.15.4 standard. While the bulbs used the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) to encrypt the passwords, the underlying pre-shared key never changed, making it easy for the attacker to decipher the payload.